This is a FED 5C, a 35mm rangefinder camera made at the F. E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune in Kharkiv, Ukraine during the reign of the Soviet Union between the years 1977 and 1990. The FED 5C is an updated version of the original FED 5 adding bright lines to the viewfinder, removing the adjustable diopter, and revised cosmetics. Like all previous FED rangefinders, it is still completely manual focus, offers an uncoupled selenium exposure meter, and a cloth focal plane shutter with a top 1/500 speed. The FED 5C was the last of the Leica Thread Mount rangefinders produced in the Soviet Union, ending an almost continuous run from 1934 to 1990.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 52mm f/2.8 Industar И-61 coated 4-elements

Lens Mount: M39 Leica Thread Mount

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder with Projected Frame Lines

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate EV needle

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Hot Shoe, 1/30 second X-sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 726 grams, 599 grams (body only)

Manual (in Russian): https://www.cameramanuals.org/russian_pdf/fed_5c_russian.pdf

Manual (similar model in English): http://www.cameramanuals.org/russian_pdf/fed_5b.pdf

How these ratings work |

The FED 5C was the last interchangeable lens FED rangefinder and last Soviet camera to use the M39 LTM when it was discontinued around 1990. Featuring a design similar to cameras made decades before, the FED 5C only offers incremental updates and a rather crude build quality. It’s ability to use a huge number of M39 lenses is it’s best feature, and assuming you can find one in good shape, should still be capable of excellent images. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 6.0 | ||||||

History

Credit: A large amount of the information that follows comes from the publication, “The Dzerzhinsky Commune: Birth of the Soviet 35mm Camera Industry” by Oscar Fricke, published in the History of Photography Journal, Volume 3, 1979.

The history of the FED camera is one of the more fascinating stories in all of camera-history-dom involving child labor, Bolsheviks, and a Ukrainian educator named Anton Semyonovich Makarenko.

Makarenko first became a school teacher in the small town of Kryukov, Ukraine in 1905. In 1914, he entered the Poltava Teachers Institute, graduating with honors in 1917, at which time he was appointed the director of his school in Kryukov.

After the Great October Socialist Revolution in 1917, Makarenko became very outspoken in his views on Soviet education. In 1920, the Ukrainian Narkompros (People’s Commissariat of Education) tasked him with creating a colony for the rehabilitation of the growing number of orphaned children, or Besprizorniki. Abandoned and dressed in ragged clothes, the Besprizorniki squatted in slums or roamed the countryside, making a living from crime and begging. Their numbers reached millions by the early 1920s, creating a serious social problem for the Soviet Union which lasted for more than a decade.

Makarenko’s colony was named after Soviet writer, Maxim Gorky as simply the Gorky Colony. Makarenko employed a military-style of regimentation and discipline at the colony in which competition between work groups was encouraged to create a sense of pride, achievement, and community. In addition to education, the students were tasked with some form of productive agricultural work.

Makarenko’s unique blend of military discipline with traditional education was largely a success. He achieved a level of reform not seen at other similar Soviet institutions. Unfortunately, Makarenko’s efforts were not fully appreciated by Ukrainian education officials, who preferred a less military style of leadership, and in 1927 forced him to resign. Later that year, Anton Makarenko was hired by the Ukrainian Police (OGPU) to supervise the F. E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune on the outskirts of Kharkiv.

The commune was named after the Polish immigrant, Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky who in his youth, led a troubled life. Imprisoned a number of times for his revolutionist ideas, in 1917, Dzerzhinsky joined the Bolshevik Party and aimed to organize Polish refugees to fight for freedom in Russia. His activism within the party allowed him to quickly gain notoriety and respect. Eventually elected to the Executive Committee of the Moscow Soviet, Dzerzhinsky earned the respect of Lenin and as a result, in December 1917, appointed Dzerzhinsky as director of a new organization called the “All-Russia Extraordinary Commission to Combat Counter-revolution and Sabotage”, or Cheka for short.

The Cheka was a broad organization whose purpose is far beyond the scope of this article, but in a very simple sense, was an early version of what would become the Soviet KGB. It’s primary purpose was to provide security for the Soviet Union, but in reality, it’s reach extended far beyond that.

In 1920, around the same time Anton Makarenko formed the Gorky Colony, Felix Dzerzhinsky became inspired by the Ukrainian Narkompros’s efforts to remedy the problem of orphaned Besprizorniki and took it upon himself to include the rehabilitation of children to the Cheka’s long list of responsibilities.

As a result, in 1921 the All-Russian Central Executive Committee established the “Commission for the Improvement of the Life of Children”, with Dzerzhinsky as it’s president. This new commission was not well received by members of the Narkompros as they felt that a strong armed government organization was not well equipped to deal with the needs of children.

It would seem their concern was valid, as over the next several years, the numbers of Besprizorniki grew. Homelessness, famine, and illness continued to be a problem in many areas of the Soviet Union.

Felix Dzerzhinsky would pass away from a heart attack after an illness on July 20, 1926. In honor of his contributions, the OGPU decided to build a dedicated children’s commune, to be named the F. E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune in his honor.

The FED commune would open in December 1927 under the leadership of Anton Makarenko whose experience at the Gorky Colony made him an ideal leader. Despite his success at Gorky, Makarenko was often at odds with the Narkompros as they didn’t always support his military style of leadership. This wasn’t a problem at FED. With the full support of the government and a brand new, even lavish facility, Makarenko was freed from the distractions at his former employer.

When it first opened, the FED commune contained 150 boys and girls, known as communards, ranging in age from 13 to 17 years old with additional children being added every year. Makarenko’s methods combined productive work and secondary education in a Marxist system of polytechnical education which sought to eliminate the distinction between physical and mental labor. This was accomplished by dividing each day into two four-hour shifts, with one shift devoted to productive work and the other to classroom instruction.

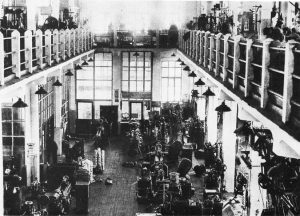

Whereas agricultural labor had been the main emphasis of the Gorky Colony, more complex types of work were developed at the FED Commune. Initially, the commune engaged in handicraft-type productions, with workshops for locksmithing, carpentry, shoemaking, and sewing. Production was started with the aid of outside craftsmen, but as commune members developed their own skills, outside help was reduced to a minimum.

The products themselves, including clothes and crudely-made furniture, initially went to serve the commune’s own needs, but orders were soon accepted from outside as well. In this way, the commune became a completely self-supporting institution and a source of considerable pride.

The value of the daily production rose steadily, and communards received wages which rose as the skill and value of their work increased. The commune even had a marching band and a wide range of clubs, including drama, various sports, photography, and service-type clubs for improving conditions within the commune. The Dzerzhinsky Commune had become a complex community and would soon undertake even greater challenges.

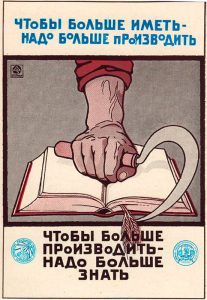

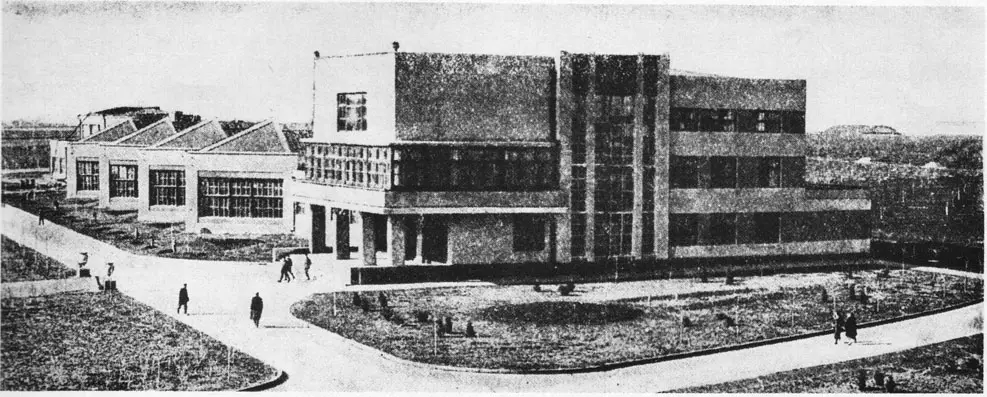

In September 1930, a new worker’s facility of the Kharkiv Engineering Institute was established at the FED commune to bring the communards up to normal university entrance standards. More importantly, the commune decided to construct it’s own full-fledged factory and begin a new industrial phase in it’s life. This undertaking would lay the groundwork and create the experience for an even more ambitious project soon to follow.

Using funds accumulated from the sale of their products, and with the aid of a state loan, a new two-story building was erected for the manufacture of portable electric hand-drills. The communards took an active part in the construction, and the building designed to house the machinery for the manufacture and assembly of the drills as well as additional sleeping quarters, was completed in November.

To cope with the commune’s new activities, the number of communards was increased to 300, now with an average age of between 15 and 20, and including 50 girls. By the end of 1932, the number reached 340, at which point there was one adult for about every four communards. These adults directed the work; they included engineers, technicians, mechanics, instructors, managers, clerks and hired workers who did some of the difficult operations and machinery repairs. Communards participated in all aspects of the production and had the opportunity to learn several different skills.

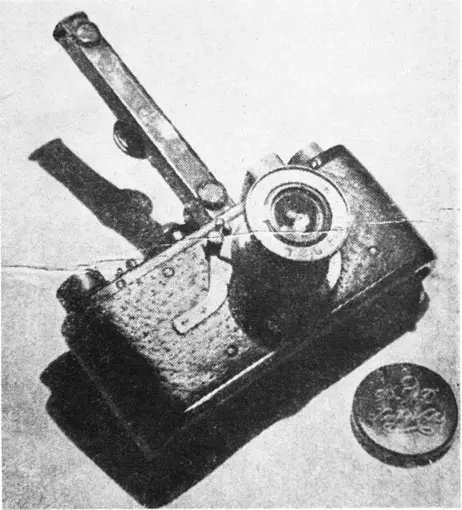

With the increased capacity of the new FED factory, in June 1932 it was decided that a copy of the Leitz Leica would be built at the FED commune. The need for a quality Soviet made camera meant that the USSR would no longer have to rely on imported cameras from Germany and become even more self-sufficient. On June 21, 1932, a special experimental department for the manufacture of Leicas was established at the commune.

On October 26, 1932, the first three Soviet Leicas were completed. The cameras were exact duplicates of the Leica A, complete with accessory rangefinder. The new cameras were shown in the November 5th issue of the official Soviet government newspaper, Izvestiya. The fact that this announcement was made in such a high profile publication shows the high degree of importance which must have been attached to the event.

The quality of the new Soviet Leicas was praised in the Izvestiya article. The writer enthusiastically claimed that “the Leningrad Optical Institute, having examined the lenses, acknowledged their higher quality in comparison with similar foreign-made lenses”. The 50mm f/3.5 anastigmat lenses of these first cameras were made in Leningrad at the Experimental Factory of the All-Union Optical Industry Association (VOOMP) in cooperation with the State Optical Institute (GOI), also in Leningrad.

The FED commune devoted 1933 to planning and preparing for camera production while the manufacture of electric drills continued at it’s normal pace. The challenge for the commune was a great one as making a Leica was much more demanding than making wooden chairs or even electric drills. With about 300 parts, tolerances to a micron and exacting optics, nothing like the Leica had ever been made in old Russia. New techniques had to be mastered and new equipment had to be made. A detailed production and financial plan was drawn up with considerable help from the State Optical Institute. Construction had begun on a new building to house the factory, with a planned capacity of 30,000 cameras per year.

By 1934, every part of the FED camera, including it’s lenses, was made in the FED factory. The camera was now a copy of the Leica II with it’s integrated rangefinder. From a distance, the only obvious differences (besides the name) between a FED camera and Leica II was the absence of an accessory clip and a different finish. The FED factory struggled to replicate the finish, so early models were painted in a black lacquer. By the end of 1934, a total of 4000 cameras had been made.

Also in 1934, two other Soviet made Leica copies were produced, the VOOMP Pioneer, and the Geodeziya FAG. The VOOMP Pioneer is almost identical in appearance to the FED, but the Geodeziya FAG had minor cosmetic differences such as a rectangular viewfinder window and changes to a couple screw locations. Production of both the Pioneer and FAG cameras were discontinued by early 1935 with only a couple hundred examples ever made. In my research for this article, I could not find any clear reason why these cameras were ever made in the first place.

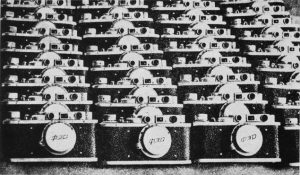

Over the next few years, the FED camera would receive incremental changes to it’s appearance, lens selection, and improvements to build quality. Reception to the new camera was extremely positive and both solved the problem of not having to rely on imported cameras from Germany, but also to produce something more affordable for photographers to purchase. Demand for the new camera was so high, that photographers began to clamor for needed accessories such as enlargers, developing tanks, slide projectors, and additional lenses.

This demand stressed the capacity of the FED factory far beyond what it’s original purpose was as a rehabilitation center. As a result, changes came to the leadership, and in July 1935 Anton Makarenko was relieved of his duty and transferred to another position in Kyiv. The FED commune’s daily operations continued largely unchanged for the next two years after Makarenko’s departure, but by 1937 the FED factory was turned over to the authority of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD for short, also the successor to the Cheka).

It is unclear how day to day operations might have changed under the NKVD which was a military type organization, but with the FED Commune’s very positive reputation, and the success of the FED camera, it is unlikely that significant changes were made. Workers likely continued to receive salaries and benefitted from other amenities at the factory, but there is no way to be certain.

Production of the FED camera continued over the next couple of years with incremental updates to the original design. Cameras with top 1/1000 shutter speeds and f/2 lenses were produced in 1938 along with a myriad of minor cosmetic updates.

On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union and began targeting areas with high concentrations of industry and agriculture like Kharkiv. As German forces advanced, Soviet forces evacuated many industrial enterprises such as the FED factories to safety in Berdsk, beyond the Urals, while demolition teams destroyed much of what could not be moved. On October 25, 1941, Kharkiv fell to the Germans and over the course of the next couple of years, “scorched earth” policies employed by both the Germans and Soviets completely obliterated the FED camera factory and the buildings of the former Dzerzhinsky Commune.

After the war, the Soviet Union began to rebuild it’s optics industry. This period of history is not well documented, and many specific details are not known. Official Soviet figures for camera production show a total of ten cameras produced in 1945, increasing to 5700 in 1946, and 91,500 in 1947, but it’s not clear where these cameras were made. About 1800 special NKAP (Red Flag) cameras were produced in 1946 in honor of the FED workers who had to evacuate their homes during the invasion. These cameras have a special inscription on the top plate which can be seen in the image of the camera to the right.

With the entire FED factory and all of it’s administrative buildings completely destroyed in the war, it is unlikely that a fully operational production facility could have been rebuilt in that short period of time. Perhaps these early post war cameras were all assembled in Berdsk from left over parts from before the factory was destroyed, or perhaps the numbers are simply wrong, we’ll likely never know.

What we do know however, is that in 1947, camera production at the Krasnogorskii Mekhanicheskii Zavod (KMZ for short) factory near Moscow would create their own version of the FED camera called the Zorkiy (iy in Russian, one i in English). Early versions of the Zorkiy were identical to the FED, some even containing both FED and KMZ logos on the camera’s top plate. The only other difference was the inclusion of an updated Industar-22 coated lens.

Full scale production of FED cameras would not resume in Ukraine until 1949, likely after the original factories were rebuilt. For the next 6 years, FED and Zorkiy cameras would be produced concurrently. Although based off the original designs, cameras produced in the KMZ were built both for domestic and export use, whereas FED cameras were largely sold within the Soviet Union. It is said that export Zorkis had a higher build quality, in an effort to show the world that the Soviet Union was a capable force in the optics industry.

By the mid 1950s with production at full capacity, the design of the FED camera was nearly 20 years old, and it was time for an update. Starting in 1955, FED would start updating the original formula with new models featuring incremental changes.

The FED 2 came first, which had an all new die cast body with a new shutter that was much more accurate than the original design. The camera’s size increased in every dimension, but with the larger body came significant improvements including a longer 67mm wide coincident image rangefinder, a removable film back, self timer, flash synchronization, strap lugs, a new rewind lever, a threaded shutter release button, and an adjustable diopter, making the camera easier to use for people with poor vision.

In 1961, the FED 3 made it’s debut, shortening the rangefinder base and redesigning the top plate to make room for a slow speed escapement, returning a full range of shutter speeds from 1 second to 1/500 like the original FED. The FED 3 also came standard with a self-timer and flash synchronization.

Only three years later, in 1964 the FED 4 was released, which was very similar to the FED 3, but added an uncoupled selenium exposure meter with top plate match needle display. Both the FED 3 and FED 4 were initially offered with a film advance knob, but later changed to a lever in the middle of the camera’s life cycle. Also, both the FED 3 and FED 4 were exported to West Germany and sold by the large photographic retailer, Foto Quelle as the Revue 3 and Revue 4.

In 1969, a prototype camera called the FED 7 was produced based on feedback the factory had received from photographers. Only four FED 7s were thought to have been made, but the camera was never put into production. The FED 7 shared most of the same features as the FED 3 and 4, including the coupled rangefinder, uncoupled selenium exposure meter, M39 interchangeable lens mount, and self-timer, but had a completely new body. The new body was wider and had more squared off edges, compared to the rounded sides of all other FED cameras. The wider body allowed for a longer film advance lever that was said to be easier to use. The camera also had a hinged back for easier film loading, a bottom plate rewind lever, and an automatic resetting exposure counter.

All images above courtesy, ussrphoto.com.

The FED 7 was an attractive camera, and the prototypes seemed pretty close to being production ready, but for reasons we’ll likely never know, the camera was never put into production. Another mystery is why the camera was called the FED 7 when as of the time it was being worked on, no FED 5 or 6 models existed.

In 1977, a final version called the FED 5 was released which was mostly a cosmetic redesign of the later FED 4 adding only a flash hot shoe, while still retaining the uncoupled selenium meter, top plate match needle, and film advance lever. The FED 5 was produced in three different versions, the FED 5, 5B, and 5C. The 5B had no meter and the 5C is sometimes referred to as an “economy model”, losing the diopter adjustment, but adding projected frame lines to the viewfinder. Whether or not the 5C was sold for less than the original model is not exactly obvious as by this time, the Soviet economy was very unpredictable, and these cameras were not exported to the US, so finding a comparative inflation adjusted price is difficult.

Most sources online suggest the FED 5C was produced until about 1990 but according to several comments in this Russian language discussion forum, unsold new stock could be purchased as late as 1993, suggesting there was a huge surplus in those final days. It would seem that the end of the FED 5 coincided with the fall of the Soviet Union, suggesting that perhaps the factory didn’t see a need to produce interchangeable lens rangefinders anymore, but contrary to that logic, in 1991 or early 1992, a prototype sixth camera called the FED 6 TTL was being worked on. Unlike all previous revisions in the FED family in which incremental changes were made to each new model, the FED 6 TTL was an ambitious camera, that had it gone into widescale production, would have been the most advanced Soviet rangefinder ever made.

All images above courtesy, photohistory.ru.

As the letters TTL suggest, the camera had a through the lens CdS meter powered by a battery on the rear of the camera. The meter took a reading at the film plane in a way that was very similar to the one in the Leica M5 and M6. Upon advancing the film and cocking the shutter, a hinged arm with the meter at the end would swing up directly in front of the film plane, taking a reading in a location that would be the most accurate. Pressing the shutter release would return the meter to a lower position, out of the way of the light path, the moment before the shutter would open, exposing the film.

But that’s not all, the FED 6 TTL was planned to have an electrically timed shutter that would have a range from 8 seconds to 1/2000. The shutter speed selector on the top plate only goes down to 1 second however, and doesn’t appear to offer any sort of Auto Exposure mode, so exactly how the metering system worked is unclear. It would seem that if a camera were to have such a wide range of speeds and an electronically timed shutter, that it should benefit from auto exposure, but this being a prototype, perhaps that functionality hadn’t yet been completed.

I can only imagine that the ambitious feature set of the FED 6 TTL, combined with the political and economic turmoil of what was now the former Soviet Union doomed further development of the camera, ending any hope for it’s completion. After the end of the FED 5 production and the abandonment of the FED 6 TTL, the only camera left in production in Kharkiv was the completely unrelated FED 50, which was produced up until around 1996.

Today, the entire series of FED rangefinders are well known. Along with the related line of Zorki rangefinders, these cameras are often the first or second models thought of when the topic of Soviet rangefinders is mentioned. No one model in the entire FED series is automatically better than another as each model only offered evolutionary changes from the first Leica II inspired models to the final FED 5 cameras. The one characteristic that these cameras share with each other is that they’re all pretty easy to find for not a lot of money. While they weren’t built with the same level of refinement as a German rangefinder, most are capable of pretty good images, even if the cameras are a little rough around the edges. Find a FED camera that’s been taken care of throughout it’s life and mount a nice lens to it, and there’s no reason you can’t get excellent results from it, making these easy recommendations for any camera collector, or someone just looking to get back into film.

My Thoughts

As the world watched the disgusting and vile attack of Ukraine in early 2022, many people in the camera community took to wanting to show their support for Ukraine and it’s people by shooting Ukrainian cameras. Kiev rangefinder and SLRs dominated the vintage camera collector Facebook groups, and while those are absolutely worthy cameras to load in some film into, I chose to speak to the wonderful FED rangefinders that I think some people sometimes forget are from Ukraine too.

The FED 2 is my darling Soviet rangefinder. It was one of the first I ever shot, and remains a favorite to this day, so when the topic came up in a recent episode of the Camerosity Podcast where we discussed Ukrainian cameras, it was the one I recommended. But that got me thinking, what about the other FED cameras? I have a FED 1 somewhere in my collection, but it’s close similarity to the Zorki 1 which I’ve already reviewed made me look at the opposite end of the FED timeline, to their last interchangeable lens rangefinder, the FED 5C.

This FED 5C came to me in a box of cameras long ago and I’ve let it sit on the shelf that time and when I finally decided to take it out, I remarked at how heavy it was, especially for a camera made in the late 1970s and into the 80s.

From the top, the FED 5C is a mixture of old and (somewhat) new. On the left is the very tiny rewind knob which pops up for rewinding film at the end of the roll. Very sharp ridges around the circumference of this knob are sure to cause skin abrasions with repeated use.

Beneath it is the exposure calculator for the uncoupled meter to the right. How it’s used, is by pointing the camera at your intended subject, take a reading of one of the EV numbers on the meter display from 1 to 11. Then using the calculator, make sure the inner ring is set to whatever GOST/ISO film speed you have loaded (as long as it’s between 25 and 400), and then rotate the outer ring until a matching EV number appears in the half circle opening on the ring. With the EV number on the calculator matching the one displayed by the meter, any combination of shutter speeds and f/stops that are lined up should result in a correctly exposed image. It’s not particularly difficult to use, but would have been sorely out of date by any western photographer when this camera was in production.

In the center of the top plate is the flash hot shoe, which apparently was a mid model change as early FED 5Cs did not have this. In the previous image, the plastic protector plate is covering the hot shoe, suggesting it was hardly, if ever, used.

To the right is shutter speed dial with yellow and red painted shutter speed numbers on a vinyl disk below it. The disc shows speeds 1 through 500 plus Bulb, but due to it’s shape, has no room for the 1/2 shutter speed mark. Once again, like a camera from decades before, the shutter speed dial rotates both as the camera is being wound and while firing the shutter. You can only select shutter speeds after the shutter has been tensioned as the arrow won’t point to the correct number before, further showing this camera’s primitive roots.

Next is the cable threaded shutter release, film advance lever with an almost completely useless film reminder dial, and an automatic resetting exposure counter. The exposure counter is additive, showing the number of exposures made. The film advance lever is sufficiently long to be within comfortable reach of your right thumb and requires a motion of about 180 degrees to complete. It’s feel is rather stiff and somewhat gritty, although I wouldn’t go as far as to say it was difficult to use.

The base of the camera does nothing to suggest this isn’t a camera based off a decades old design. On both sides are locking keys for reloadable metal cassettes, similar to the original Contax and Leicas of the 1930s. In the center is a 1/4″ tripod socket that looks as if perhaps there is a 3/8″ socket beneath some sort of adapter. Off to the left is the camera’s imprinted serial number. The number on the 5C is not like many other Soviet cameras in which the first two digits can date the camera. My best estimate to this particular camera’s age is probably mid 80s due to the hot shoe and use of ISO film speeds on the exposure calculator, but I honestly do not know.

The entire look and feel of the bottom of the camera is of very low quality. Although the chrome appears to be properly plated, it has a very shiny appearance, similar to cheap Chinese cameras of the same era, and looking at the metal itself, rough machining marks are on almost every surface. While no FED rangefinder ever came close to a level of quality or refinement of the original Leicas, the FED 5C is about as far as you can get from those original cameras.

Around back, there’s very little to see other than the round opening for the viewfinder, and a stamped FED logo in the upper right corner of the very shiny chrome.

The removable back and bottom of the camera reveals a rather ordinary film compartment. Film transport is from left to right onto a fixed and double slotted take up spool. The spool itself has a curious hollow design which is open at the bottom, but it works. The film pressure plate is a single piece of black painted metal with no additional provisions for ensuring smooth or flat film transport.

The FED 5C came with a variety of lenses, but most are similar to this Industar И-61 52mm f/2.8 lens which despite being rated at 52mm, is optically the same as other И-61 lenses sold over the course of many decades. It’s operation is simple and straightforward. A ring closest to the body controls focus from 1 meter to infinity and a thick ring around the front edge is the aperture ring with stops from f/2.8 to f/16. Pronounced click stops allow for easy selection of f/stops without looking at the lens, although if you wanted to adapt this lens for video, you might not enjoy them. The lens itself uses a 49mm filter thread and the front element has a deep blue coating.

Off to the sides, the FED 5C looks like a pretty typical Soviet rangefinder, with curved edges, a tall top plate, and not much else. It seems that throughout the various iterations of FED cameras, strap lugs come and go, with them missing on this one. This is unfortunate as it means the only way to attach the camera to a strap is to use the original ever ready case, or use a tripod socket strap, which I always feel is awkward.

Up front, the FED 5C has the same M39 Leica Thread Mount featured on nearly every other interchangeable lens Soviet rangefinder. The attached Industar lens on this example is said to be a good performer, but with any one of the hundreds of different LTM lenses made over the years, you can be sure of excellent images shot when mounted to this camera.

Inside of the lens mount at top dead center is the rangefinder coupling cam which like most Soviet rangefinders is shaped like a triangular finger, instead of a wheel like a genuine Leica or other Japanese Leica copies. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but one of many little areas in which the Soviet factories cut corners to simplify the design established by Leitz.

To the left of the lens mount is the self timer lever which unlike many cameras with a similar lever, is upside down. The timer works by rotating the handle in the direction of the arrow and then advancing the camera as normal. To fire the shutter, do not use the top plate shutter release, rather than tiny button that is directly above the self timer lever. Pressing this activates an approximate 10 second countdown, after which the shutter will fire at whatever speed is selected.

The viewfinder is large and bright, with a circular, green tinted rangefinder patch in the center. The FED 5C is the only camera in the range with visible frame lines to indicate the exposed image. Manual parallax marks exist which help frame your image at minimum focus. The design of the frame lines on this camera make them difficult to see as they are much fainter than the rangefinder patch and are near the extreme edges of the frame and impossible to see while wearing prescription glasses. In the image to the right taken with my smartphone, they are easier to see than they are in real life.

If it’s not completely obvious yet at this point in the review, the FED 5C was an antiquated relic from an earlier era even when the camera was new. The economics of the late 1970s and 1980s Soviet camera industry is far more complex than I could ever hope to cover, but the desire to produce rudimentary cameras that despite many shortcomings, were still technically capable of wonderful images was as appealing then as it is today. I could argue that anyone can make a great photo with a Nikon F3 or an Olympus OM-4, but it takes a bit more thought and effort to use a camera like the FED 5C.

This camera’s interesting blend of 1930s era tech, combined with some modern conveniences like a flash hot shoe, automatic resetting exposure counter, and rapid wind lever, make for a curious combination, and with prices still very, very low for almost unused FED 5Cs, they’re hard to ignore. But should you? Keep reading…

My Results

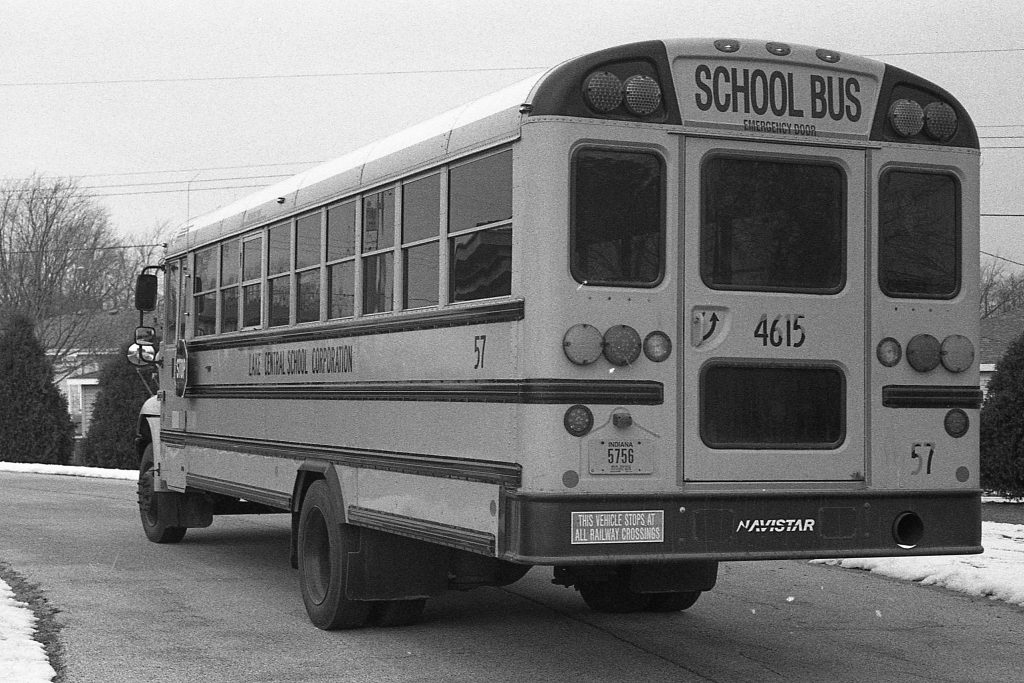

For what ended up being my one and only roll of film through the FED 5C, I chose a expired roll of Smena FOTO 65, an approximate ASA 63 speed film with an unknown expiration date. A curiosity of Soviet film from this era is that many people still reloaded metal 35mm cassettes, so single roll reloads in which film is wrapped in black paper and inserted into a cardboard box, without a metal cassette was common.

This film cannot be taken out of it’s packaging without first being inserted into a cassette in total darkness. Open the box with the lights on will expose the film, ruining it. The box it came in did not have an expiration date, but knowing the relative long life of most black and white films, I approached this film as if it was an ASA 50 speed film, and figured I’d give it an extra minute or so in the developer to compensate for it’s age…whatever that may be.

Although I am no stranger to faults from heavily expired film, somehow I thought the Smena FOTO 65 would have held up better. Extreme grain permeated every image on the roll and in many cases, my shots were underexposed, even though I shot it like an ASA 50 film. Perhaps a few extra stops of exposure would have suited it better, but I didn’t feel like trying another roll of it, so to see if I could get better images from the FED, I loaded in a second roll of bulk TMax 100.

As is the case with most interchangeable lens cameras, the results are largely dependent on the lens attached. Sure, a malfunctioning or poorly designed shutter can throw off exposure, and a camera that’s difficult to use, might cause otherwise easy exposures to be difficult to make, but largely, what you see through the lens is what you’ll get and I’m happy to say this is true with the FED 5C.

The images from the Industar И-61 lens are decent, with decent sharpness in the center, and only a small amount of softness near the edges. The vivid purple lens coating is in good condition and should help to control flare and render decently accurate colors. I only bothered to shoot black and white film through the FED 5C as the “great color film shortage of 2022” meant I had to be discriminate on which cameras I wanted to use my precious C41 stocks on. I did not attempt to make any bokeh images, but as this is a popular use for these Soviet lenses, I am sure that a bit of swirl would likely appease people using this lens adapted to digital.

An issue that permeated both rolls is an obviously malfunctioning shutter which is capping at certain speeds. To be honest, I didn’t record the camera settings for every exposure here to determine if the capping is limited to one or more speeds, but in both galleries above, you can clearly see about half of the shots exhibit the characteristic darkness on one side. On a more valuable camera, a CLA would be in order, but for this 5C, I’ll likely never pay to get it done.

Even if I had gotten more technically superior images from the FED 5C with a perfectly working shutter, they would not be enough to overshadow the crudeness of this camera. Throughout both rolls, the overall operation of the camera felt clunky and unrefined. Where the earlier FED 2 is a solidly built camera with smooth controls that feels nice in your hands, the FED 5C clearly shows that quality control and priorities had changed in the decades between when these two models were produced.

The frame lines, which were the one upgrade for the 5C from the previous model, are hard to see with prescription glasses and even when I tilted my head to see them, they were very faint. The shutter speed dial has cheaply painted on numbers that don’t perfectly line up with the speed selector and look as if they could be easily worn away. The film advance lever had an excess of resistance, felt gritty in operation, and was generally lacking in refinement. Even the chrome plating on the body, although shiny, just feels cheap.

I really love the FED 2, as I find it to be a well built, easy to use, and cost effective alternative to shooting more expensive Leica and Leica copies. My tone throughout this review of the FED 5C is quite a bit different, offering quite a bit of criticism, but I should clarify, the FED 5C technically does what it’s supposed to do, and with the Industar И-61 lens, is capable of nice shots.

The biggest pill to swallow with this camera is how out of date it’s feature set and design had become by the time these were sold. The FED 2 was made three decades earlier, at a time when it’s list of features was still pretty expected. While the Soviet camera industry wasn’t always known for innovation, I think a bulk of my disappointment with the 5C is how they couldn’t find more ways to make it better. Leitz stopped producing LTM rangefinders in 1960, and Canon in the early 70s, so for there to still be models with the same mount more than a decade after that, it would have been interesting to see what a 1980s LTM rangefinder might have been like. The FED 6 TTL hinted at that, but it was never meant to be.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/FED_5

http://www.sovietcams.com/indexd5ff.html

https://sovietcameras.org/fed-5/

https://www.photrio.com/forum/threads/fed-5c-framelines-adjustment.181727/

https://www.halfhill.com/fed5c.html

https://schneidan.com/2015/03/20/russian-ballet-the-dance-of-the-fed-5c-rangefinder-camera/

https://casualphotophile.com/2018/05/21/fed-5b-camera-review-35mm-film-rangefinder/

http://cameras.alfredklomp.com/fed5/

http://photohistory.ru/index.php?pid=1207248177857554 (in Russian)

http://rangefinder.ru/oboz/showproduct.php/product/1/cat/27 (in Russian)

I bought mine new- for a pittance. Untraceable light leaks and the worst smelling case I have ever encountered

When you shoot really out-of-date b&w film and are not overly concerned about grain, I’d suggest developing in Rodinal diluted 1:100, 70F, for 40 minutes with agitation when you first submerge the film and once again at the 20 minute mark. It compensates well for under/over exposure, in my experience, producing uniformly contrasty negatives even if the film’s actual ISO was a stop or two away from the light meter’s reading.. Do any other readers agree or disagree with this?

I’ve shot a couple dozen rolls with the FED 5C and I definitely agree with most of your criticisms. It is not a sophisticated camera but given a bit of attention it can make a decent shooter.

The shutter curtains on these cameras are often not correctly tensioned, with too much tension on the rollers causing capping and making the film advance feel stiff and harder to operate. The shutter also becomes more quiet at the proper level of tension. It’s not too hard to retension the curtains, if you have an old CRT monitor or TV you can also make sure the curtains run parallel. It’s also worth taking off the top plate and cleaning the gunky yellow grease off of all the cogs and relubing with gun oil. Taking the lens off one should carefully apply a drop or two of oil to the top and bottom of the rollers as well. The drag from the old lubricants (or lack of any) can throw the shutter off as well.

Another thing that improves the experience is attaching strap lugs to the front of the camera. The best place are the respective upper corners of the leatherette.This provides the correct balance when using the Industar 61 and the camera won’t tilt back or forth when carried around the neck. I use little brass eye-bolts cemented into place with JB Weld.

All of this can be done by someone with little technical know-how, like me, for instance.

I’m very sorry to correct you but child’s labour used only til 40-50’s. After that period FED factory was included not only in photographic industry but in military, so quality control which you can see with FED-2 is one of the consequences of this reform.

Also sorry for my possible mistakes, English is not my native language

I also have FED-5B made in 1993. It came to me in original box and this date was mentioned in original papers.

Thank you!!

I have a roll of film in my FED 5C camera and love it!! Love the feeling of shooting on a 100% mechanical camera in this age where all is digital.

Now i am seeking a medium format film camera to add to my collection and start shooting with it for my soul. Any suggestions?

Regards!

Glad you liked the review! The 5C is very capable of making excellent photographs.

As for getting into medium format, that is a loaded question that depends highly on your budget and what size images you are looking for. The most cost effective entry is usually 6×6 or 4.5×6 folders as there were a ton made, and most still work. Twin Lens Reflexes like the Rolleiflex are great options too and very fun to shoot, but are considerably more expensive and likely will need some level of cleaning or service to work properly.