When it comes to collecting cameras, you have many options. Some people like myself can latch onto any camera as long as it appeals to me in some way, but others are more discriminate. Some people specifically seek out SLRs or rangefinders, some prefer ones from a specific brand or country, and some go for film formats. If you’re a film format kind of guy, you can go very large with 4×5, 8×10, or even 20×24 cameras, but if compactness is your priority, there’s a whole world of subminiatures to look out for.

The term “subminiature” is pretty vague and is generally used to refer to any camera that makes an image smaller than what a 35mm camera makes. Back in the early 20th century when cameras were quite large, the first 35mm cameras were considered “miniature cameras”. An exposed image of 24mm x 36mm or even 18mm x 24mm was considerably smaller than the roll and sheet film cameras of the day.

It’s worth noting that cameras making images smaller than 35mm existed as far back as the 1800s with models like the Kemper Kombi and Robert Gray Detective Camera making images as small as your thumbnail, but for the purposes of this article, the term “subminiature” is usually used for small cameras of the 20th century.

In this, the 102nd Keppler’s Vault, I bring to you three articles, the first from the October 1953 issue of Modern Photography and two more from the August 1963 issue of Popular Photography.

The first is titled “The New World of Sub-Miniatures” and comes at a time when the greatest number of tiny cameras were in production. For Japanese makers, cameras smaller than 35mm were essential as the post-war prices of film was still very expensive, so the need for economical cameras that expose smaller images helped keep costs down. For the non-Japanese models mentioned, the benefits of tiny cameras that were unobtrusive to carry and shoot was also appealing.

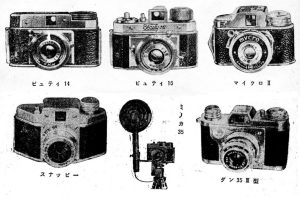

Unlike 35mm and larger cameras in which a similar shape and control layout were common, in the subminiature world, there was no standard. No less than 35 models are in the image to the right show the incredible variation in size, shape, and design, from simple watch cameras to full scale single and twin lens reflexes.

The article starts out simple enough, defining the name ‘subminiature’ as any camera using film narrowed than 35mm. It suggests that while a great deal of early subminis were used in clandestine photography, that is not their only purpose, in fact, after the war, the selection of subminis meant that photography could be captured in a great number of places that larger cameras either wouldn’t fit or be appropriate.

The rest of the article is a sort of buyer’s guide for the available models. Special caution must be taken to assure that anyone in the market for one of these cameras in 1953 to ensure that a supply of film for it could easily be obtained.

The next article, and the first from August 1963, is a 9-page look back at the history of subminiature cameras, covering some of the most popular models from the past present and future. It starts off with a look back at models like the Expo Watch Camera from the early 20th century and early Detective Cameras, then briefly covers the history of the creation of Walter Zapp’s Minox and other 16mm based Japanese cameras by Minolta, Steky, and Riken, and American 16mm subminis by Whittaker and Universal both of which I have in my collection and hope to review someday.

Where the second article differs from the earlier one, is that ten full years had passed between the two and while subminiatures were still popular, it took almost that entire time for manufacturers to agree on compatible film formats. Prior to that, many cameras used proprietary film stocks that were not compatible with other models. If you invested in a Whittaker Micro 16 and wanted to upgrade to a Goerz Minicord, you’d need all new film.

The author, Joseph Cooper gazes into his crystal ball and predicts that subminiature cameras would continue to develop and might one day reach the same level of status as current 35mm models did. He suggests that with more and more compatible films, we might see a greater number of models with more and more advanced features.

Interestingly, this 1963 article already acknowledges the existence of Kodak’s then new Instamatic format which still used 35mm wide film, but produced slightly smaller 26mm x 26mm images using an easier to load and unload cassette. I think Cooper unknowingly touches upon the reason that his optimistic prediction of future submini advancement would never come, when he suggests that Eastman Kodak refused to comment on film stocks smaller than Instamatic. No matter how popular the format might have been, without Kodak’s full support, it was doomed.

With the benefit of hindsight, Eastman Kodak would eventually release a 16mm film format called Pocket Instamatic type 110 film, but with only a few exceptions, would be used in inexpensive entry level cameras. While a few 110 SLRs were made, they hardly reached the status level of 35mm cameras.

A curious omission from Cooper’s article is that other than a passing reference to novelty cameras, nothing is said about the huge number of Japanese “Hit Style” cameras like the Mycro that shot paper backed 17.5mm film.

While a huge number of these cameras were cheaply built and considered toys by most people, there were some high quality examples like the Toko Tone and the Konishiroku Snappy that I think would have deserved a mention.

The third and final article isn’t really about subminiatures, but rather covers the resurgence in popularity of compact half frame 35mm cameras which the magazine refers to as “Sub-35” cameras to differentiate them from true subminis who usually use some type of 16mm film or similar. Like the other articles, there’s some history about half frame starting with the Herbert & Huesgen Tourist Multiple and other models like the ANSCO Memo and Universal Mercury CC.

The main part of the article is a large chart which serves as more of a buyer’s guide to currently available Sub-35 models. Many of the models are dedicated half frame cameras, but there’s a few special purpose full frame cameras like the Nikon S3M and Alpa 6C which were also available in half frame format. A curious addition are a couple Kodak Instamatic cameras which I think is a stretch to consider subminiature or “Sub-35” since the film stock is still exactly 35mm wide. Perhaps the novelty of what was then a new format made them worthy of inclusion.

Today, the entire world of subminiature cameras is very appealing to collectors both due to the huge number of available models and tremendous variance in design. Unlike many medium format and 35mm camera systems in which a somewhat generic design is used over and over again, subminis exist in nearly every shape and form factor.

As for the article’s predictions on future success of the format…it’s complicated. As mentioned earlier, while 110 Pocket Instamatic would bring 16mm film to the masses, it barely caused a blip on the development and sales of larger film formats. With few exception, 110 cameras were inexpensive and cheap cameras that did not appeal to professional photographers.

Cameras like the Minox and Tessina would continue to be sold for decades to come, they didn’t change much from their original formula. Faster lenses, exposure meters, and even AE would eventually make their appearance in some models, but otherwise the “hey day” of submini was already nearing it’s end by the time both 1963 articles were written.

If you are a new or existing camera collector and have concerns over shelf space, or have become tired of so many cameras with the same basic shape and design, perhaps a subminiature collection is something to consider. A word of warning however, is that the small size of these cameras usually does not translate into small price tags as many models featured in the articles above have prices far higher than larger formats!

One might make the argument that the best of the APS point’n’shoots, gear like Canon’s stainless steel-clad ELPHs, are also miniatures – they certainly are sub-35 in overall dimensions, and are built to provide fine photos over many years’ service. Shame about the film disappearing. I can find fresh 620, 116 and 616, but not APS.