This is a Fujicaflex Automat, a medium format Twin Lens Reflex camera produced by Fuji Photo Industries in Japan starting in 1954. The Fujicaflex was the company’s first and only attempt at a twin lens reflex camera, shooting 6cm x 6cm images on 120 format roll film. The Fujicaflex was a very attractive camera with a long list of features not found on other TLRs of the same era. Starting with dual 5-element f/2.8 Fujinon lenses, the Fujicaflex had a fine focus wheel that allowed it to focus closer down to 2.3 feet. It has a unique combined focus and film transport knob on the side that performs both functions depending on if it’s pulled in or pushed out. It also has an automatic film transport, both a left and right handed shutter release, self timer, and range of shutter speeds from 1 to 1/400 seconds, making it one of the most capable cameras of it’s style.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

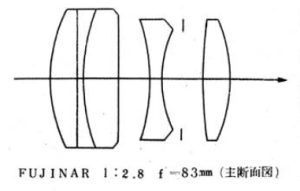

Lens (Taking and Viewing) : 8.3cm f/2.8 Fuji Fujinon coated 5-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 4 feet to Infinity (2.3 feet using Close Focus) / 1.2 m to Infinity (0.7m Close Focus)

Viewfinder: Waist Level Coupled Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Seikosha Rapid Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/400 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync, if hotshoe, flash sync speed

Other Features: Self-Timer, Magnifying Glass, Sports Finder, Close-Up Function, Dual Shutter Releases, Shutter Lock

Weight: 1298 grams

Manual (single page, in Japanese): https://mikeeckman.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/FujicaflexManual.jpg

How these ratings work |

The Fujciaflex Automat is one of the largest and most unique looking medium format TLRs ever made. It has an excellent 5-element f/2.8 taking lens that is capable of some of the best images you’ll ever see in 6cm x 6cm format. It’s list of innovative features is very long and has things like a combined shutter advance and focus knob, twin shutter release sockets, and a backwards film transport that eliminates creases in film as the camera sits, yet, the complexity and uniqueness of the camera made it very expensive and short lived. Finding one of these cameras, especially in working order, is very difficult and very expensive. If you can find one and afford it’s price, you’ll know that you own a very special camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.3 | ||||||

History

The name “Fuji” comes from Mount Fuji, which is the tallest mountain on the island of Japan. At a height of 3,776 meters, it is only the 35th tallest mountain in the world, but is still considered to be a source of inspiration and reverence to the Japanese people. As such, the name “Fuji” has been repeatedly used in the names of several companies, from Banks, Steel Companies, and several electronics companies.

The Fuji company that produced a number of film cameras in the middle of the 20th century dates back to 1934 when it was formed as Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd. This company was an offshoot of an earlier Japanese company called the Dai-Nippon Celluloid Company who was formed in 1919 as Japan’s premiere maker of celluloid film and other products.

Fuji’s earliest products were photographic film, but it didn’t take them long to start producing other optical products such as cameras and lenses.

In the early 1940s, Fuji would expand their operations and begin making optical products solely for the Japanese military. In my research for this article, I could find very little information about what types of products these were, but most likely they were lenses for scopes, binoculars, and other war-time products.

Eventually, Fuji would reorganize into several smaller divisions, all managed under the same corporate umbrella, but what little I could find on it was hard to follow. As best as I can tell, these separate Fuji companies would all fall into a single entity known as the Fujifilm Group.

After the war, Japan’s economy was devastated, and the United States had an interest in rebuilding it to make Japan a partner in the Pacific region. In order to get the country back on it’s feet, they needed an influx of money, so during the Allied Occupation of Japan, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP for short) began looking at what Japanese industry survived the war, and tasked them with building products that could be exported to bring in money.

Companies like Fuji, Nippon Kogaku, and Canon all had expertise with optics, so cameras became a popular product to build as there was an established appetite for them. Since this needed to be done quickly, these Japanese companies were not given the luxury of long development times to come up with all new models, so instead, most new Japanese cameras were heavily bases on existing pre-war German models.

In April 1948, Fuji would release it’s first camera, a medium format folding camera called the Fujica Six which would shoot 6cm x 6cm images on 120 roll film. Fuji likely followed the trend of combining it’s own name with a ‘-ca’ suffix from ‘camera’ to come up with Fujica, just like Leica, Konica, and Nicca had done.

The Fujica Six was a rather ordinary folding camera, built in the style of German folding cameras like the Zeiss-Ikon Nettar and the AGFA Isolette with a horizontal folding door which revealed a self erecting leaf shutter and lens. The earliest cameras came with Lotus leaf shutters with top speeds of 1/200 and an f/4.5 triplet lens. With a Japanese domestic price of ¥5,250, this converted to just under $15 in US dollars at the time, a meager price to pay, but it was a start.

The Fujica Six, like many competing Japanese models with similar specs was very successful and as the company’s experience making cameras grew, it evolved with better shutters and lenses, new features, and eventually a new body.

In November 1950, an improved model was released called the Fujica Six IIBS, which replaced the simple folding viewfinder with a rigid optical finder mounted to the top plate. The shutter was synchronized for flash, had a self-timer, the lens was a Fuji designed f/3.5 triplet. This model was heavily sold through military PX stores to US solders for use while being deployed or to be taken back home, without having to pay any import taxes or fees.

By the early 1950s, Fuji’s reputation grew along with that of the entire Japanese Optical Industry. Companies like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Canon, and Mamiya were increasingly seen as quality competitors to established Japanese brands. Although Fuji’s priority wasn’t as a camera maker, it’s camera division got working on a number of new and innovative models.

One such model was a new medium format twin lens reflex camera. Other Japanese camera makers like Riken (Ricoh) and Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta) had already been producing 6×6 TLRs since before the war, but in the early 1950s, there wasn’t yet a clear best Japanese TLR. Minolta Autocord and Yashica TLRs were still a couple of years away from their dominance in that segment, so Fuji must have wanted to throw their hat into the ring.

The exact origin of the Fujicaflex’s development is a mystery. In my research for this article, I found very little information about when it started development, who at the company was responsible for it’s design, any images of prototypes, or possible later revisions of the camera.

The Japanese language article to the right which comes from an unknown publication seems to suggest the camera was in development for two years before it actually went on sale, but my best attempts at Google Translate did not turn up much more useful information.

The fact that it existed is about all that I’ve found. Certainly a camera with such a unique design and features never seen on another camera should have a story about it, but I have yet to find it.

What we do know is that the camera was available in 1954. An article in the October 1954 issue of Modern Photography to the left suggests that the cameras were produced about 100 units per month and that the camera was not for sale in the US. I’ve seen images of what appears to be the cover of the Japanese user manual and the only references to the camera I’ve found are all in Japanese, further suggests the camera was never exported here.

A single page quick reference guide, which I have listed above as the camera’s manual is the only online evidence of the camera’s user manual. I am not even convinced that this single page sheet is original to the camera, and not a “fan made” guide produced years later. One thing that is interesting about it however, is that it includes the lens diagram to the right proving that the f/2.8 Fujinar is a 5-element in 3-group design, something that I couldn’t find anywhere else online.

When sold in Japan, the Fujicaflex had a price of ¥65,000 which is three and a half times more than a much simpler Japanese TLR like the Pigeonflex (predecessor to Yashica) at ¥18,000, and more than double the price of a Minolta Autocord at ¥29,800.

It is very difficult to convert historical foreign currency to current day US Dollars, but I found evidence that the Minolta Autocords usually sold here in the United States for around $100, if the Fujicaflex was imported here and it sold for more than double of an Autocord in Japan, it stands to reason it would have carried a retail price of over $200 which entrenches on Rolleiflex territory.

Beyond what I’ve included here, the Fujicaflex’s history is a mystery. If the camera was produced for only a year, and 100 were made at a time, then it’s plausible only 1200 were ever made. My gut tells me that number is probably a little higher than that, but probably not much. I found no evidence the camera was produced or sold past 1954, and we know now that Fuji never made another TLR.

Perhaps they bit off more than they could chew, finding that the world wasn’t ready for an innovative and high quality Japanese TLR. Perhaps they figured that they were better suited to selling film and modest cameras that would drive sales at greater volumes. Who knows. What we do know is they were made and they do exist.

Today, Fuji is still a respected maker of both digital cameras, and within other areas of the Japanese tech industry. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, the company would release a wide range of 35mm and medium format rangefinders, SLRs, half frame cameras, and simple point and shoots. The company would never make another 6×6 TLR again, and while I could not find any specific reason why, my best guess is that they felt as though they could better compete in other segments.

The Fujicaflex is an extremely desirable camera, for it’s history, unique operation, looks, and rarity. Many collectors have never seen one in person and I was extremely formulate to be able to spend a few months with this example. If you ever get a chance to pick one of these up, be prepared to pay quite a large sum for it, but if you do, at least you’ll know you have a one of a kind camera!

My Thoughts

Kurt Ingham sure likes Fuji cameras, or specifically, he likes sending ME Fuji cameras. In the past two years, Kurt has generously loaned me the Super Fujica-6, three different Fuji 645 models (which I have yet to review) and the Fujicaflex Automat.

Even before I met Kurt, I had a fondness for the brand, having given positive reviews to cameras like the Fujica Drive, Fujica Automagic, and Fujicarex II, and while each of those cameras were attractive and capable cameras, the Fujicaflex Automat takes the cake perhaps as the most attractive camera I’ve ever held. This thing exudes style. From the glorious arched Fujicaflex typeface above the taking lens, to the camera’s many soft curves and frosted metal patina, this thing is gorgeous…

…and heavy! At a weight just under 1300 grams, the Fujicaflex is the heaviest medium format TLR I’ve ever come across, save for the Mamiya C-series with their huge bellows focusing rack and interchangeable lenses. The Fujicaflex downright dominates other TLRs like the Rolleiflex Standard at 776 and the Yashica-D at 925 grams. Even the equally plump ANSCO Automatic is just a hair lighter at 1289 grams, making this the kind of fixed lens TLRs.

There’s no doubt the Fujicaflex demands attention by it’s looks, but it also requires it for it’s operation. In the world of mid 20th century 6cm x 6cm TLRs, a huge number of them take their ergonomic and design cues from the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex. For good reason, it was a heck of a camera, but for the most part, once you’ve handled one, picking up any number of competing Rollei-style TLRs feels familiar. Sure, some of those cameras like the Flexaret and Minolta relocate the focus arm beneath the lens, and other cameras tweak the location of the film advance knob/handle or the shutter release, but there’s not much that’s different. The Fujicaflex Automat however, is that those cameras.

Things start off innocent enough looking down upon the top of the camera. In front of the viewfinder hood and above the shutter plate are two Rollei style rectangular windows that display selected f/stops in red from f/2.8 to f/22 and shutter speeds in black from 1 to 1/400 plus Bulb. That the top shutter speed is 1/400 instead of 1/500 is not unusual for a medium format Japanese TLR as attaining even coverage at faster speeds over the larger shutter opening was a challenge that only the Germans had seemed to master at that point.

Changing both shutter speeds and f/stops is done by two wheels conveniently located on opposite sides of the taking lens. Turning the wheels are both uneventful except when selecting the top 1/400 shutter speed. Like other leaf shutter cameras, I found that selecting the fastest speed is easier to do with the shutter uncocked. If the shutter is cocked, you can still do it, but it is much harder.

Looking down the camera’s left side is the flash sync port, two pull out posts which are used when loading in a new roll of film, and the ornate depth of field scale. This scale is coupled to the focus distance of the camera. Focus distances are indicated in feet on a curved wheel that spins as you focus the camera. Fixed lines pertaining to various f/stops approximate your depth of field at various distances.

On the camera’s right side is the coupled exposure counter and a round shutter readiness indicator. When the indicator is red, the film has already been advanced and the shutter is cocked, ready to fire. After firing the shutter, this indicator turns white, letting you know you must advance the film again.

Also on this side of the camera is a large wheel that looks like it could be the focus knob or the film advance knob. But which is it? Turns out, it’s BOTH! As indicated by some printing on the knob it self, turning it serves double duty depending on if it’s pushed in or pulled out. Push it in and rotating the knob moves the lens standard fore and aft, but pull it out and turn it, and now you’re advancing the film. It’s pretty easy to tell the difference as when focusing the knob turns easily, but when advancing the film, a considerable amount of effort is required as you are not only advancing the film, but also incrementing the exposure counter, and cocking the shutter.

The back of the camera features a large exposure guide in English giving recommendations in shutter speeds and f/stops depending on the scene and time of year. Interestingly, at the bottom, it mentions Double Exposures in certain situations, yet I’ve found no way to accomplish double exposures on this camera. If anyone knows, please let me know! There is no red window on the Fujicaflex as it has an automatic stop film advance.

The bottom has a film type reminder switch with four options, PAN, SS, COL, and E. In front of it is a tripod socket, which on this example appears to have a brass 1/4″ adapter in it. While I made no attempt to remove it, it does look like this camera was originally designed for 3/8″ tripods and had this adapter screwed in place. Finally, in front of the tripod socket is the key for opening the film compartment. In it’s normal position, the key lays flat and the door is locked with the letter “S” next to a marker. To open the film compartment, fold out the key and give it a twist so that the letter “O” is next to the marker and the door opens. I really like this method for opening and closing the camera as there is zero chance the film compartment cam accidentally open with the key folded shut. You have to unfold it before it will turn, which is one step safer than other TLRs which have doors held close by friction, or a wheel that can accidentally back off.

With the film compartment open, we see what at first looks like a run of the mill TLR film compartment. Upon further glance, you’ll notice that film transport is opposite that of most German TLRs like the Rolleiflex. The supply side of film is at the top of the camera, with the take up spool on the bottom. The distinct advantage to having the supply side on top rather than the bottom is it prevents the film from having to make a 90 degree turn before being exposed. It was thought that if film is left partially shot in a camera, a crease could form in the film at that corner, which then becomes part of the next exposure. With the supply spool at the top, the film only come across the 90 degree turn after the image is made.

Another noticeable difference between the Fujicaflex and other “Automat” TLRs is the absence of any kind of rollers that you must feed the film through, or arrows that must be aligned with the START mark of a new roll of film. The way the Fujicaflex was designed is you simply install in a new roll of film attach the paper leader to the take up spool on the bottom, close the door, and start advancing the camera and it would detect when to stop at the first exposure. Unfortunately, this is one area of the camera I was unable to test as the camera had a malfunctioning film transport, possibly suggesting that Fuji’s clever implementation of this feature wasn’t very reliable.

Up front, there are a few interesting things to see. On opposite sides of the taking lens are the shutter speed and aperture control wheels mentioned earlier. Looking at the face of the camera, the wheel on the left is the aperture control and is in easy reach of the photographer’s right hand, and on the right is the shutter speed control and is in reach of the photographer’s left hand.

Immediately above the aperture control wheel on the side of the lens plate is a geared wheel and chrome button. This is the close focus control and lock button. Under normal operation, this wheel is locked and allows for normal focus of the camera. Press and hold the lock button while turning the geared wheel and both the taking and viewing lenses rotate away from the camera, acting as a sort of build in close-up attachment. With the lens fully extended, close focus is extended from the normal 4 foot limit down to 2.3 feet (1.2 meters down to 0.7 meters). This close focus capability is unique to the Fujicaflex offering pseudo-macro capabilities without the complexity of a bellows system or removable close focus attachments like on other TLRs. Close focus mode however, does not offer any automatic parallax correction, instead requiring you to use two triangles near the upper left and right corners of the viewing screen to indicate the close focus upper limit of the viewfinder.

On the opposite side of the viewfinder lens is a sliding vertical lever that activates the camera’s self timer. Interestingly, the self-timer can only be engaged with the shutter cocked, eliminating any chance it could be accidentally set when the camera is in storage with the shutter uncocked. If you do choose to leave the shutter cocked, directly below the taking lens is a sliding horizontal lever which acts as a shutter release lock. With this lever to the right, a red signal appears and the shutter release buttons are locked.

Did you just say shutter release buttons…as in plural buttons? Yes, I did. A feature of this camera I never read about online and didn’t even discover until after I shot my first roll through the camera, the Fujicaflex has two shutter release buttons…or at least two sockets for one. When this camera came to me, the shutter release button was clearly below and to the left of the taking lens, in easy reach of the photographer’s right hand, exactly where it is on a Rolleiflex. However, opposite that location on the other side is an open socket, which I initially thought was another flash sync port, is a screwed port for a second shutter release. Simply unscrew the shutter release button on the left and move it over to the right and it still works. I am unsure if when this camera was new if it could be purchased with two shutter releases, or if you were intended to move it to whichever side you prefer. This certainly is a welcome feature to left handed people, or those who want to keep a constant handle on the focus knob with their right hand and operate the shutter release with their left.

Up top, lifting the hood reveals a fairly ordinary waist level finder, like those found on many other TLRs. The viewing screen has an etched 5×6 grid with a plus sign in the center. Two small triangles in the upper right and left corner are used when the camera’s close focus feature is used. The viewing screen is pretty bright in the center with vignetting in the corners. The screen lacks any noticeable Fresnel pattern, which had that been included, would have improved corner brightness. Notice the two parallax correction marks near the top of the viewing screen noting the 2.3 foot minimum focus position.

Inside the upper lid is a hinged magnifying glass for precision focus. To release the magnifier, a metal sliding button on the right side of the viewfinder hood is pressed toward to front of the camera to release it. Closing the magnifier is just a matter of folding it shut. With the magnifying glass in the up position, the center of the top lid can be manually pushed down into the viewfinder, and combined with a small square hole on the back side of the hood, the camera has a built in sports finder for fast action shots. When shooting objects in motion at or near infinity, hold the camera at eye level and compose your shots with the sports finder and you can easily obtain accurately focused image without having to use the viewing screen.

When reviewing cameras, I don’t often comment on the camera’s case as often I don’t have them, and in the cases where I do, they get thrown into a box in my basement, never to be seen again. For the Fujicaflex, the leather case is extremely well built, made out of a thick caramel color leather that is still soft and supple after all these years. An interesting thing about the case is the front face of the case has a metal plate that is the only place that shows the cameras full name, Fujicaflex Automat. The word “Automat” does not appear anywhere on the camera itself.

The Fujicaflex Automat is a spectacularly interesting camera to hold. It’s beautiful, it’s heavy, and it’s loaded with knobs, buttons, and wheels in strange locations that will cause the first time user fits. This is definitely a camera in which you need to read the manual first, something that is very difficult to do today as I’ve never found any copies of the camera’s manual online.

I’ve shot my fair share of 6cm x 6cm TLRs, and the only camera that’s come close is the ANSCO Automatic Reflex 3.5, another very large, very pretty, and unusual mid century camera. How does the Fujicaflex Automat hold up however? On paper, this behemoth of a camera sounds like a winner, but just because something looks tasty, does not mean it is!

My Results

When the Fujicaflex arrived, it looked to be in great shape, but Kurt admitted to never having shot it before. When it came time to load in the first roll of film, I immediately noticed there was an issue with the film transport. After fiddling with it for a couple of days, I determined that a pin that is used to determine if the back is open or closed was not functioning, so the camera always thought it was closed. The film transport would never reset, even after loading in a new roll unless I manually turned a geared shaft in the film compartment with my finger.

I could load film into the camera, but because the camera didn’t realized I had opened it, it would immediately act as it if was shooting film, even though I was still on the paper leader. My workaround for this was to take the camera into a dark bathroom and pull out the paper on a new roll of 120 film until I could feel the start of the actual film, and then load the film into the camera with the photographic film already to go on the first exposure and shoot the camera like that.

For the camera’s first roll, I picked a semi-expired roll of Fuji Neopan 400 that was donated to me by site reader, Alan King. Thanks Alan!

As I usually do after shooting a roll of film, the exposed roll goes into a drawer until I have enough rolls to make it worth my while to go into the basement and develop a bunch at once. That would take me a little bit, but once I did and I saw the results from the Fujicaflex…HOLY COW! I expected the images to be nice, but they had a sharpness and pop that I had not seen on other 6×6 TLRs. Sadly, the film transport problems were not the camera’s only obstacle as I lost several images as the shutter didn’t open properly, so only four images from that first roll were usable, but they were some of the best images I had shot in a while.

Initially, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to risk another roll of film in the camera, but after seeing the results, I decided to give it another go, this time learning from some of my previous mistakes in the hope that a second roll, this time of slightly expired Kodak Portra 160NC would yield more properly exposed images.

I still had some issues with the shutter on my second roll, but being aware that sometimes it wouldn’t fire and that I shot the entire roll on the same day in pretty quick succession without letting it sit too long yielded nine out of twelve color exposures.

The images that the Fujicaflex Automat can make are undeniably excellent. Fuji was no stranger to good optics and they broke out their entire bag of tricks when making the 5-element f/2.8 Fujinar lenses on this camera. It is clear that Fuji wanted to make the best possible TLR they could that was not only attractive, but also included a huge list of features, some of which the world had never seen.

Assuming that was their intent, I can absolutely say mission accomplished…. (Here comes the BUT)

In going out of their way to implement new features to the camera and create new features and a design no one had ever seen before, Fuji unintentionally made a camera that was unnecessarily complicated, heavy, and expensive.

While out shooting with the camera, I felt as though I was handling a fragile artifact. While I would definitely recommend taking good care of any vintage camera while out shooting, the rarity and unorthodox operation of the Fujicaflex was constantly on my mind while out shooting it. That I had to keep listening for the shutter to properly fire each time I pressed the shutter release added even more anxiety to the shooting process.

I’ve shot many rare cameras and many with questionable operation, and I’ve received feedback from readers of this site suggesting I shouldn’t be able to make declarations about a model without having a fully CLA’d perfectly working example. To those people I say, find me a perfectly working CLA’d Fujicaflex, and I’d be happy to give that one a go, but until that happens, my opinion of the shooting experience of the Fujicaflex is mixed, at best. I definitely loved the idea of the close focus wheel. In the color gallery above, the two images of the yellow flowers and the flower pot were both done at minimum focus. Parallax is extreme, but the close focus mark at the top of the viewfinder helps with this.

The combined film advance and focus knob was a great idea, but I don’t know that it’s any better, or faster than other Japanese TLRs like the Minolta Autocord or Ricoh Diacord who use paddle or bottom mounted focus levers that can be controlled with your other hand. It is a good idea that Fuji gives you the option of both a left and right hand shutter release, as requiring your right hand to advance the film, focus, and fire the shutter is not elegant. The viewfinder was bright enough for outdoor use and certainly on par with other 1950s TLRs, but had this been a camera I expected to use with regularity, I would have looked into a brighter focus screen like those sold by Rick Oleson.

We have the benefit of hindsight to look back at the last 70 years and see that the Fujicaflex Automat did not sell in large numbers. Although I was never able to find any contemporary reviews for it, I can almost guarantee that any that were written likely talked about the camera’s unique operation and high price tag. In 1954, anyone looking for a world class TLR with a fast f/2.8 lens almost certainly bought a Rolleiflex 2.8. Anyone considering a Japanese TLR did it because they expected a less expensive camera that worked the same way. The Fujicaflex was neither.

Of course, that it was so different from anything else and so rare is what makes the Fujicaflex Automat so collectible today. Used copies of this camera in nice shape easily exceed $1000, far above that of a run of the mill Rolleiflex. If you can find one that works, as you can see, the images it makes are world class. The Fujicaflex is the rare example of the camera that has it all, distinct beauty, innovative features, low production, and excellent performance.

The Fujicaflex Automat may be one of the prettiest cameras I’ve ever seen and it’s images are some of the sharpest I’ve ever shot, but it’s price is far beyond what I would be comfortable paying to add one to my permanent collection. If however, your budget is larger than mine and you are looking for a unique statement piece, I wholeheartedly recommend one!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Fujicaflex

https://yashicasailorboy.com/2021/11/08/fujicaflex-superman-as-a-tlr/

http://www.tlr66.com/fghij/fujicaflex.php (in Japanese)

http://kochicame.blog108.fc2.com/blog-entry-56.html (in Japanese)

https://lab.hendigi.com/fujicaflex/ (in Japanese)

https://koyasu-camerabox.sakura.tv/wp/?p=924 (in Japanese)

https://koujiyacamera.hamazo.tv/e3807358.html (in Japanese)

Thanks,Mike- great review! I’m not that well off, but I am at a time of life (pushed by some scary health encounters)when I can stretch my resources a little for ‘bucket list gear’ Reading your pieces makes me feel I’m being less selfish – you make the cameras ‘available’ to a large number of enthusiasts-with accurate research, real insight, and outstanding writing!

How cool a camera! Being a Fuji fanboy, i wish to get one in good working condition one day!

About the double exposure. I think it doesn´t mean you can get double exposure, but that you should “double your exposure” on the given months from the exposure guide.