This is a Zenobia 35 F2, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Zenobia Optical Co.,LTD of Japan between 1957 and 1958. This version of the camera has an upgraded f/2 lens compared to a second model, simply called the Zenobia 35 that has a 46mm f/2.8 Zenobia O-Hesper lens, but is otherwise the same. The Zenobia 35 was the very last in a line of cameras produced by Zenobia, formerly called Okada Kōgaku and Daiichi Kōgaku, makers of the Waltax and Zenobia folding cameras. The Zenobia 35 has an interesting left handed paddle that advances the film and sets the shutter before each image, very similar to that of the Konica III from the same era. The rest of the camera is fairly standard for a Japanese rangefinder with a good lens, leaf shutter, and coupled coincident image rangefinder. The maker of this camera went out of business shortly after this model’s introduction, making them scarce today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 44mm f/2 Zenobia Optical O-Hesper coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity (2.5 feet to Infinity Indicated)

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder, 0.9x Magnification

Shutter: Rectus MXV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, Automatic Resetting Exposure Counter, Wind Up Motor Drive

Weight: 732 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Zenobia 35 was a short lived, but well built camera that served as the swansong for the Zenobia company, who was more well known for producing folding “semi” cameras. This version has the upgraded f/2 Zenobia O-Hesper lens which renders sharp images on par with those found on many A-list Japanese cameras. The left handed film advance lever is the camera’s most unique attribute, and works similarly to that of the more successful Konica III. The Zenobia 35 is a nice camera, with good build quality, an excellent viewfinder, and a solid lens that when found in good working condition is capable of pleasant, if unremarkable images. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

Ask 100 collectors to name their favorite Japanese camera brand, and I’d be willing to bet a pint of Three Floyd’s Zombie Dust that no one will pick Zenobia. In addition to being a short lived and low volume camera maker, the company that eventually became Zenobia went through multiple name changes and ownerships during their short life, further confusing their legacy.

Ask 100 collectors to name their favorite Japanese camera brand, and I’d be willing to bet a pint of Three Floyd’s Zombie Dust that no one will pick Zenobia. In addition to being a short lived and low volume camera maker, the company that eventually became Zenobia went through multiple name changes and ownerships during their short life, further confusing their legacy.

The company that would eventually make the Zenobia originally operated under the name Okada Kōgaku Seiki K.K. from the mid 1930s to around 1951. The early history of the company is very thin and hard to follow. I have not been successful at finding anything more than the same word for word write-up at both Camerapedia and Camera-Wiki.

Japanese camera makers from the early parts of the 20th century were not very well organized and difficult to trace. Many companies produced “white label” goods to be sold by small shops with no makers marks. Others were copies of other cameras, and many still were built, branded, distributed, and sold by different entities, all with their own unique names. From around 1910 to the 1930s, it was common practice in Japan for camera makers to manufacture and distribute cameras under a “Camera Works” name. Wikipedia has a really good article that gives at least a partial explanation of this along with some examples. Rather than repeat that information here, I recommend you read that from their site if you want to know more.

The earliest evidence of Okada Kōgaku was around 1936 when the Walz camera was first produced. The Walz was a Japanese strut folder taking 3cm x 4cm pictures on 127 format roll film. The Walz was very similar to the Foth Derby, a German made strut folding camera that also took 3cm x 4cm pictures on 127 film. The Walz was advertised as being made by the Walz Camera Works, which according to the Camera Works Wikipedia article mentioned above was most likely a fake name given to hide the original manufacturer of the camera. Page 745 of the McKeown’s Price Guide to Antique and Classic Cameras references a Japanese book named ‘Kokusan kamera no rekishi’ which states that the Walz was in fact, made by Okada Kōgaku.

The Walz was in production only one year. It disappeared from the market in 1937. Little is known of what the company was doing for the next several years, perhaps functioning as a distributor or maker of camera parts like some of the other “Camera Works” companies.

In 1940, Okada Kōgaku would release two medium format folding camerasm both based off the German made Zeiss-Ikon Ikonta A, known as the Waltax and the Okaco. The name “Okaco” was an abbreviation of the company name Okada Kōgaku, and only appeared on the earlier models. The Waltax would become the company’s first successful camera, and would be made before and after World War II.

After the war, the Waltax would continue production, but in December 1947, a revised model, the Waltax II was introduced which added support for 620 film in addition to 120 film, a new top plate with a fixed and offset viewfinder, and double exposure prevention. Then again in mid 1949, the Waltax III would debut which had all of the features of the Waltax II but added flash synchronization. According to information on Camera-wiki.com, the Waltax II and III did not appear in many Japanese publications and may have been for export only to western countries.

In 1951, two new models called the Waltax Senior and Waltax Deluxe were introduced and heavily advertised in Japanese publications. The Senior was nearly identical to the Waltax III and may have been just a renamed model. The Deluxe was the same as the Senior, except it had a self timer.

In late 1951, Okada would change it’s name to Daiichi Kōgaku and from that point an, all models of the Waltax were renamed to the Zenobia and continued to be sold until 1957. The Zenobia’s design was a continuation of the Waltax family and would receive incremental updates throughout it’s life.

In 1956 a model called either the Super Zenobia SR or just the Zenobia SR (both names were used and referred to the same model) featured a coupled rangefinder and a Daiichi-Rapid shutter with a top speed of 1/500 seconds. It was this same year that the company’s name changed once again from Daiichi Kōgaku to Zenobia Kōgaku. Models released during this period had a lens with an engraving that said Zenobia Opt. instead of Daiichi Opt.

Unlike the company’s first name change, this time the name change was due to problems the company had with a union over a labor strike in 1954. Okada/Daiichi/Zenobia dedicated most of its development to the Waltax/Zenobia folding camera, and it is believed that the company did not expect 35mm film to take off as quickly as it did in the 1950s. Sales of the folding models was starting to drop rapidly and the company attempted to lay off about a third of its labor force.

In 1954, Daiichi would start work on a Japanese Leica copy which would be called the Ichicon-35, but after the company’s name change to Zenobia, a version of the camera reportedly called the Zenobia 35 was created. It is unknown whether or not any of these Zenobia 35’s were ever created, but the image to the right seems to suggest they did. Whether or not this image is authentic is real or a fake is not clear, but I’ll share it here just in case.

Before the Zenobia 35 could ever be released it’s development would be transferred to a separate company called Mejiro Kōgaku and the camera’s name would change once again to the Honor S1 and it would remain in production until 1959.

Although Daiichi/Zenobia’s Leica copy would never be produced, the company would eventually release a 35mm camera in 1957 also called the Zenobia 35. This camera was a more traditional fixed lens rangefinder, but came with a left handed “paddle” shutter release. The design of the camera bore some resemblance to the Konica III from 1956, but as to whether any connection was intentional, accidental, or otherwise, has never been proven.

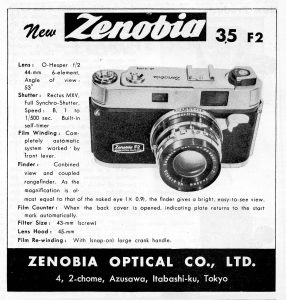

The Zenobia 35 was only produced until 1958, but there were two versions of the camera available, one with a 44mm f/2 Zenobia Optical O-Hesper lens, and a second with a slower 46mm f/2.8 O-Hesper lens. Apart from the lens, the only other change to the slower model was the engraving of the Zenobia logo on the top plate had a different typeface. There are conflicting reports which came first, the f/2 or f/2.8 version, but according to a chart on this page, both models were released at the same time with the f/2.8 version simply called the Zenobia 35, and the f/2 version called the Zenobia 35 F2.

According to camera-wiki, the camera was advertised in various Japanese publications between 1957 and 58, with the f/2.8 version selling for ¥17,000. I have never seen any of these ads though and cannot confirm that price. If so, would have meant it was one of the least expensive 35mm Japanese cameras with a coupled rangefinder and f/2.8 lens. The ad to the right for the Zenobia 35 F2 appeared in the Nov/Dec 1958 issue of CamerArt magazine, confirming it was still on sale at that time, but does not list a price.

The Zenobia turned out to be a pretty decent camera, however constant changes in Zenobia’s leadership, past legal and financial troubles, an extremely competitive market, plus the growing popularity of SLR cameras forced the company into bankruptcy and production of the camera was halted. It is unknown how many examples of these cameras were made, but my best guess is, “not many”. While researching this article, a worldwide search on eBay and Yahoo auctions turned up none for sale.

Today, Zenobia has a generally good reputation among collectors of mid century Japanese cameras. Most however, are only familiar with their folding cameras, and not their short lived entries into 35mm film. In fact, I would guess that very few reading this article even knew the company made 35mm cameras.

This model would have been a capable competitor to contemporary Japanese rangefinders, it comes with a good lens and shutter, a large and bright viewfinder, and a clever film advance that was used by other camera makers. There is a lot to like about the Zenobia 35 F2, so if you ever have a chance to pick one up, I definitely recommend it!

My Thoughts

In early 2022, I received a message from friend and site reader, Randy Reames who had previously donated to me his Revere Eye-Matic EE 127 which I reviewed in October 2019, saying that he had another interesting camera for me to take a look at. The camera he proposed sending me was this unusual Zenobia 35 with the f/2 lens. I vaguely recalled when working on my early review of the Zenobia C folding camera, that the company had also made a 35mm model, but having never seen one, I gladly accepted Randy’s offer and the camera was on it’s way.

Although I had seen pics of a couple Zenobia 35’s online, it wasn’t until I handled one that I realized how attractive the camera was. The camera had clean lines, a large viewfinder, and a left hand trigger film advance that strongly resembled the Konica III. In fact, the more I handled the Zenobia 35, the more I thought that perhaps this was intended to be a copy. Not an identical copy mind you, more like a “hey, we like your camera so much, we’re going to do the same basic thing with just enough differences that you can’t say we ripped you off” kind of copy.

Whether or not the Zenobia is a copy of the Konica is debatable, but what’s not debatable, is that this is a high quality and well built camera. At a weight of 732 grams, the Zenobia is a slim 4 grams lighter than my Konica III which tips the same scale at 736 grams. Side by side, the two cameras are also nearly identical in every dimension, with the Zenobia a hair wider, and taller, further adding to the narrative of similarly inspired cameras.

Up top, the Zenobia has a unique looking rewind knob with folding handle. Unlike most rewind knobs of this style, the one here has a sort of trapezoid shape, and the folding handle is hinged on two sides, giving it a bit more rigidity. Next is the accessory shoe and Zenobia engraving on a slightly elevated top plate.

On the right side is the cable threaded shutter release button and combined ASA film speed reminder dial. Since there doesn’t need to be room for a standard top plate film advance lever, there is more room for the large exposure counter, which can be seen beneath a glass window. Opening the film door automatically resets the counter to an “S” position and it counts up, showing how many exposures have been made since the door was last closed.

Flip the camera over and on it’s base is a sliding film transport switch for advancing or rewinding the film and a 1/4″ tripod socket on the side. Ideally, tripod sockets should be centrally located to help balance the camera when sitting on a tripod, but the fast nature of the camera’s unique film transport system meant that this camera was almost always used hand held. Another thing worth noting is that on the base of the shutter is a knurled tab for changing focus. Although you can grip the focus ring around the entirety of it’s circumference, having this tab at the bottom allows for easy fingertip control while stabilizing the camera from the bottom.

The camera’s left side has a sliding latch for opening the film door. Lift up on the latch near the top and the right hinged film door will open. From this side you also get a look at the film advance lever on the front of the camera. Both sides of the Zenobia have forward facing metal strap lugs which is a nice touch as many rangefinders from this era went without lugs, instead requiring you to use the ever ready case.

Around back, there’s not much to see other than the round eyepiece for the viewfinder, and embossed into the body covering in the lower right corner of the door, the words “Made in Japan”.

At first glance, the Zenobia’s film compartment appears rather ordinary, but has a few unexpected features that not every camera from this era had. Film transports from left to right onto a non-removable metal single slotted take up spool. The spool rotates clockwise, which means the film wraps around it opposite the direction it is in the cassette, which is said to help promote better film flatness across the film gate. Twin metal sprockets aided by a metal roller on the inside of the film door help guide the film onto the rails, reducing the likelihood of film getting jammed. A somewhat small pressure plate on the inside of the door is covered in divots which help to reduce friction as film passes over it. Inside of the film gate is a metal baffle right behind the lens which is there to help reduce internal flare from light bouncing around inside of the film compartment. Without a baffle, some lenses can cause a drop in contrast as unwanted light hits the film as it is being exposed. Finally, the inside of the door hinge and inside of both film door channels are felt light seals which are still in tact, showing no sign of degradation like foam light seals would have.

Looking down upon the Zenobia’s Rectus-MXV shutter, we see everything you’d expect to see from a more common Copal or Seiko shutter. Closest to the body is a fixed depth of field scale, and right in front of it the black focus ring. As mentioned earlier, a metal tab near the bottom of the camera allows for easy focus changes. The total throw from minimum to infinity focus is around 30 degrees, which is rather short. This has the benefit of using a quick flick of the finger to move within the entire range, however, the motion is fast, making precise focus slightly difficult.

Next are two metal rings with knurled edges for the aperture and shutter speeds. The aperture ring has prominent click stops at each position from f/16 to f/2, but the shutter speed ring turns smoothly. I was very pleased to see that unlike many fixed lens rangefinder cameras from the mid to late 1950s, the Zenobia lacks any sort of LV or EV coupling. This means that both the shutter speeds and f/stops can be chosen in any combination without having to overcome or decouple them. I’ll keep beating that dead horse and say I am almost universally against these types of systems, although some companies implement it better than others. Thankfully, Zenobia avoided it altogether! If there is one unfortunate ergonomic snafu, it’s that in between the shutter speed and aperture rings near the 7 o’clock position around the shutter is the flash sync post which gets in the way of my finger every single time I reach for the camera. While sync posts on leaf shutters are almost always on the shutter itself, this location is quite annoying. Thankfully, the location of the self-timer lever near the 9 o’clock position around the shutter does get in the way.

Up front, you can more easily see the locations of the red tipped self-timer lever, MX switch, and the annoying location of the flash port. The focus tab below the shutter is very visible, as is the entire film advance lever. You can activate the film advance with your left hand in two ways. The first, is to use your index finger, almost like if it was a left handed front shutter release. I found this orientation very comfortable and instinctive to use. I would be willing to bet, that the first time anyone were to pick up this camera, that’s how they would use it.

A second way, using your left thumb while supporting the bottom of the camera with the rest of your hand allows your left index finger to rest perfectly on the focus tab beneath the shutter. Using your thumb to press down on the film advance means you never have to move your hand to focus the camera. Pressing down on the film advance lever with your index finger means you have to reposition your hand each time you want to change focus, and then back to advance the frame again. This method is slightly less obvious the first time you pick up the camera, but is the way I prefer. I was unable to find a user manual for the Zenobia, nor any promotional material, but looking at the manual for the Konica III which has an identical film advance, the Konica manual recommend using the thumb method as well.

The Zenobia’s viewfinder is pretty typical for a late 1950s Japanese fixed lens rangefinder. The green tinted viewfinder has a pink tinted rectangular rangefinder patch in the middle. There are no projected frame lines, exposure information, or anything else to see within the viewfinder. While the entirety of the viewfinder is bigger than those found on rangefinders from the 30s, 40s, and early 1950s, I found it difficult to see the edges of the image while wearing prescription glasses. Without glasses, I could press my face closer to the camera to fit it all in, but since my glasses aren’t optional, that didn’t work for me.

The Zenobia 35 is a surprisingly nice camera built by a company that most people probably never heard of before. It uses a design similar to the Konica III, replicating it’s user interface perfectly. The camera is well built and the film compartment has a number of subtle touches that suggest a well thought out camera. It is disappointing that the viewfinder wasn’t a little bit better, but for the era, and price range of this camera, I can’t really complain.

Of course, cameras were built to make images, so what kinds of images can the Zenobia make?

My Results

In an impromptu trip in early June 2022 to Central Camera after their grand re-opening, I picked up a couple rolls of fresh Kentmere 100 as my supply of bulk black and white film was packed away in boxes during my basement remodel, so when it came time to test out the Zenobia 35, I reached for one of those two 36-exposure rolls of Kentmere and took it with me on my daily activities. I have shot Kentmere film before and found it to be a pleasant, if unremarkable medium speed black and white film, but it had been a couple of years, so I was looking forward to seeing what kinds of results I got from both it, and the camera.

As I saw the images coming out of the Paterson tank after developing the roll of Kentmere, my description above that the film is pleasant, but unremarkable applies to the images from the Zenobia as well. To be clear, these are solid images. I found the sharpness from the f/2 Zenobia O-Hesper lens to be good across the frame with a tiny bit of softness near the edges. Some internal haze that I saw when looking through the glass with the shutter open presents itself in images where the sky is present, but doesn’t seem to affect shadow details or lower contrast scenes much. As I only shot black and white film, I cannot comment on it’s color accuracy, but I see no reason to believe it wouldn’t have at least been on par with countless other mid-century Japanese rangefinders.

The Zenobia is a pleasant, if unremarkable camera in both it’s performance and operation. The camera feels well built and likely would have held up to regular use, giving it’s original owners many years of satisfactory performance.

As I said in my review of the Konica III, I did not love the left handed film advance. The force required to push it down felt a little too much for my left index finger, so I found myself wanting to use my thumb instead, which worked well enough, except the orientation required for your left hand to use your thumb, makes changing focus difficult, so your hand is in a never ending cycle of changing positions to focus, fire, focus, fire. I didn’t hate it, I just felt it offered no advantage to more traditional lever advance cameras.

The viewfinder is probably the camera’s greatest strength as it’s size and contrast made focusing very easy, even in low light situations. In the gallery above, the image of the indoor swimming pool was shot in less than ideal fluorescent light through a glass window, and I had no problems with accurate focus.

Although I could never find a price that the Zenobia 35 F2 might have sold for, my guess is that it was on the lower end of it’s competition, making for a solid economical purchase. Compared to more reputable Japanese makers at the time, the camera’s unique operation, fast f/2 lens, good build quality, and reasonable price should have attracted some buyers. That the camera is so hard to find today suggests that it never had a chance to reach it’s market potential, likely due to the company’s looming demise and poor distribution, which is a shame as this is a decent camera.

For collectors today, the Zenobia 35 is an uncommon curiosity, especially when found with the f/2 lens. If you like cameras with unorthodox film transports like the Zeiss-Ikon Tenax II or Konica III, this camera is a must have. If you don’t love that style however, it won’t do anything to change your mind. As a shooter, the Zenobia is pleasant, if unremarkable, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Zenobia_35

https://ameblo.jp/foto-pooh/entry-12632805238.html (in Japanese)

http://www.ajcc.gr.jp/Zenobia_35_Report.pdf (in Japanese)

Mike,

Thanks again for doing such a nice and thorough review on the Zenobia. Hopefully some other reader will step forward with more information about it or let us know if there are more out there in the wild.

Randy Reames

I’m gonna behave, and avoid making comments about the “Rectus” shutter ….

Perhaps I am due for a list of “Unfortunately Named…Shutters”! 🙂