One of the greatest stories I’ve heard while collecting and researching old cameras is how one of the greatest cameras ever made was created.

The story goes that in 1911, a Zeiss employee named Oskar Barnack was recruited by his friend and former colleague, Emil Mechau to work for a small German company who made microscopes. This company was Ernst Leitz GmbH and the appeal of switching employers was that at Leitz, Barnack would have much more creative freedom.

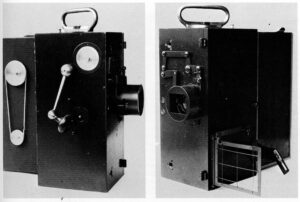

Around 1912, Barnack was tasked to work on a new aluminum bodied motion picture camera that would use 35mm cinema (or kine) film. Oskar Barnack had severe asthma which made him weak, and the aluminum body was chosen to keep weight to a minimum, compared to the heavy wooden cameras of the day.

While working on this new motion picture camera, Barnack often struggled to get the exposure timings right because film emulsions of the day were very inconsistent and often required adjustments to get the exposure correct.

Since cinema film came on very long spools, a large amount of film could be wasted if the exposure was incorrect. Barnack set out to develop a type of film tester that would expose a single frame of a roll to test it’s speed, and once he could determine the correct exposure for that roll of film, he could calibrate his motion picture camera to expose the rest of the roll consistently.

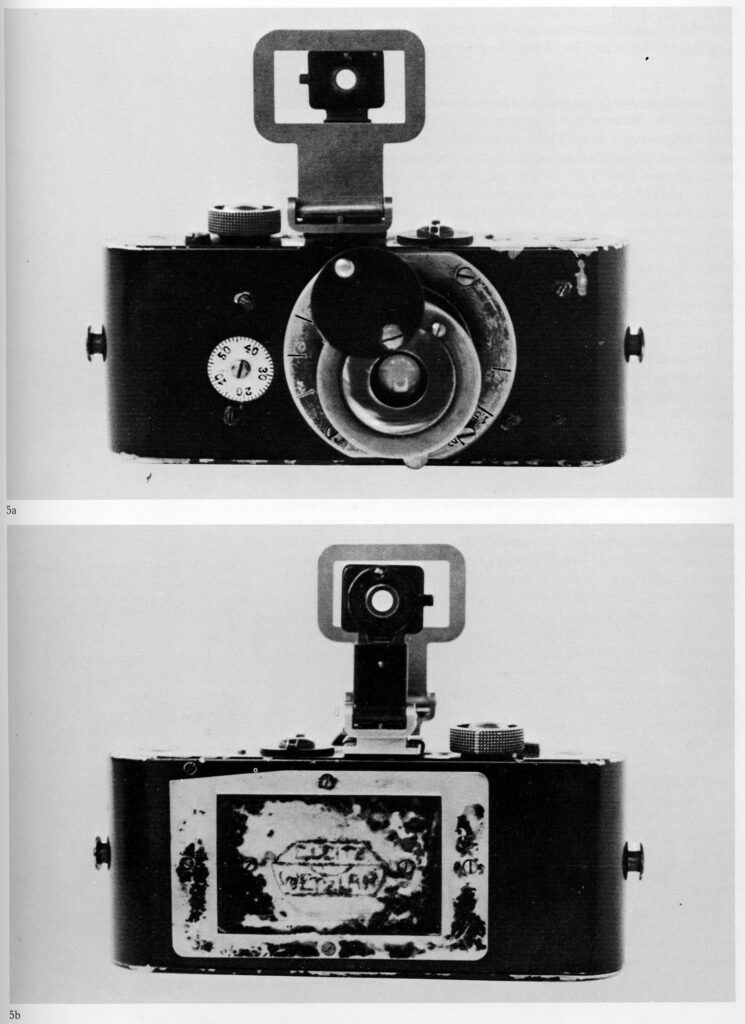

Barnack’s first prototype of his single frame tester was completed in 1913 and two versions of this original design were made, both of which were very similar to each other. Barnack originally referred to his new invention as the Liliput Camera, but are retroactively referred to today as the Ur-Leica, as the prefix ‘ur-‘ means prime, original, or first.

For many years, only the original one was thought to exist, but eventually a second showed up. Both original Ur-Leicas are very similar with small changes to the design of some of the screws being the most obvious difference, but the second one has less paint loss, suggesting it wasn’t used as much as the first.

Fun Fact: According to Leica: A History Illustrating Every Model and Accessory by Paul-Henry van Hasbroeck, early versions of Barnack’s prototype exposed images that were 24mm tall and 38mm wide. The 38mm width is the exact distance between 8 perforations of 35mm kine film. This resulted in images with no spacing as each image touched the one next to it. Barnack later revised his design to add a 2mm space between each image, reducing the exposed image width to 36mm.

Since Barnack’s creation was never intended to be a complete camera and his employer had no interest in producing still cameras, the prototypes were set aside while Barnack and Leitz focused on other projects.

The Third Ur-Leica

Most versions of the Leica story say that a decade later, Germany’s economy was in ruins after their loss in the first World War and companies like Leitz needed to find ways to generate income. The microscope business was slowing and with still photographic cameras become more and more popular, someone at the company, perhaps Barnack himself, came up with the idea of revisiting his shutter speed tester to make a fully functioning 35mm camera.

While much of this story is probably true, it leaves out a third Ur-Leica which is thought to have been made between 1918 and 1920. The third Ur-Leica is very different from the first two, and show several changes that hint at the later Null-Series Leicas which Barnack had yet to build. The existence of this third Ur-Leica suggests that Barnack had envisioned his earlier exposure tester camera becoming a real photographic camera prior to 1923 when the Null-Series cameras were thought to have been started.

Looking at photos of the Nr 3 camera, we can see a prominent exposure counter on the front face of the camera, a folding viewfinder on top, domed shutter release, and most significantly, an adjustable slit shutter. Unlike the shutter in the first two Ur-Leicas whose slit has a fixed width, the one in this prototype can be changed from as little as 1.8mm wide to 50mm wide, effectively offering variable shutter speeds. A setting for Z, or Bulb was also available.

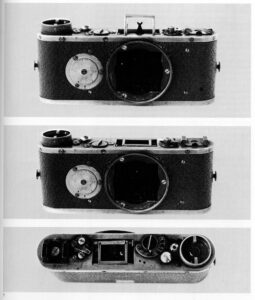

Null-Series Leicas

While we do not know Barnack’s original intent for the third prototype, or the exact year it was built, we know that in 1923, he would create an all new camera, simply called the “Leitz Camera” or “Leica” for short, by evolving the Ur-Leicas and improving them for photographic use. A limited run of cameras were built and were given to local photographers for their feedback. Three distinct batches of Null-Series cameras were built. Nrs 100 – 106 were the first to be built, 107 – 121 were from the second batch, and a third, consisting of Nrs 126 – 130 were later released as Leica I prototypes that were likely intended to be Null-Series cameras. It is generally assumed that no cameras with serial numbers 122 – 125 were built. Although these prototypes were never commercially sold or given any kind of “official” Leica name, in the world of Leica history, these first cameras have become known as the Null-Series or sometimes as the Leica 0.

The feedback from these original Leicas was extremely positive, which encouraged Leitz to continue to refine the camera and build it in larger quantities, eventually becoming the Leica rangefinder we know today. The rest is history, Leica rangefinders would become not only the most popular 35mm camera in the world, but also the most copied 35mm rangefinders, with millions of very similar copies made in countries all over the world from the Soviet Union, United States, England and others. The company still exists today as a maker of the best film and digital cameras. It is very possible that the company might not have survived the 1920s had it not been for Oskar Barnack’s almost accidental creation of what would become the company’s most successful product.

The Mother of the Ur-Leica

So far, nothing I’ve said is new. The story above has been told many times, even on this very site, and for the better part of the past century has been the standard history of the Leica and Oskar Barnack’s role in creating it.

But what if I told you that Barnack’s 1913 Liliput Camera wasn’t the first time he built something like it? What if Barnack had other exposure tester prototypes that he worked on prior to the one we know today?

The mystery behind Barnack’s first exposure tester starts with a story published in issue 50 of the German language magazine VIDOM from May 1992, in which author Georg Mann visits the Leica Museum in Solms. While there, Mann came across what he referred to as a ‘photo housing’ that had as of then, never been discussed in any known collector’s circles. The photo housing was kept in a sheet metal cabinet that was said to contain a number of early samples of Oskar Barnack’s work in it.

This strange device shared a similar rounded body and general dimensions of an early Leica, but none of the features of anything he had seen before. The body was made of aluminum and had a wooden inner core. A hollow brass tube extended from the front of the device and behind it what looked to be some kind of sliding dark slide. The back had a hinged brass door that could be swing open to reveal what looked to be the back of a film compartment. The bottom was removable, revealing a film compartment that strongly resembled an early Leica, equipped with a perforated sprocket shaft and hand made take up spools. The housing had no lens, focal plane shutter or viewfinder.

The camera had a red label taped to the back with “M 875” hand written on it. This number was a museum inventory number, and was not original to the camera. Beyond this label, the housing had no other identifiable markings on it. Georg Mann inspected the housing, which this article will continue to refer to as “M 875” and found that it had dimensions very similar to a Leica Model A. It’s overall width of 133mm was but half a millimeter from a Leica and it was within 2.5mm in height.

Beyond his initial observations, neither Georg Mann, nor anyone at the museum had any other information regarding M 875, but there was very strong evidence that this was likely an earlier version of Barnack’s Liliput Camera. In the years since that article was written, M 875 was transferred to Leitz’s private collection and a search for more information about it had begun.

Georg Mann’s article, “Die Mutter der Ur-Leica” (The Mother of the Ur-Leica) is presented below, both in the original German language, and translated to English below. I don’t actually have permission from anyone to post this, as I didn’t know who to ask, but if someone has an issue with it appearing here, please let me know!

Compared to the original Leica Model A or even the Null Series Leicas from 1923, the 1913 Ur-Leica was primitive, but at least it had a focal plane shutter, a lens, a way to focus it, and a viewfinder. Whatever M 875 is, it was much more crude. There is considerable debate as to whether or not M 875 is even complete as it lacks a lens or anything resembling a typical shutter.

As of late 2022, the current theory is that perhaps the 5cm f/3.5 Carl Zeiss Jena Kino Tessar lens from Barnack’s motion picture camera was used with the device as it fits perfectly inside of the hollow brass tube. It is entirely possible that Barnack’s original intention was to swap the lens back and forth between his cine camera and the exposure tester.

What we don’t know about M 875 is much greater than what we do know. When was the camera made? When did Barnack come up with the idea for an exposure tester? Did he ever envision a photographic still camera before he told anyone? Which lens was supposed to be attached to it? Were there even more prototypes from before M 875 or after, and if so, what happened to those?

The images in the gallery below were taken of the original M 875 camera, in possession of the Leitz Museum in Wetzlar by LHSA member, Bill Rosauer in October 2022. All images below are used with permission.

What we do know for sure is that this was an Oskar Barnack creation and that the Leica’s origins date back farther than the 1913 exposure tester that is commonly known about. Leitz is currently engaged in ongoing research into the camera’s history and origins. As of December 2022, the device is still in possession of the Leitz Museum in Wetzlar.

Ray Morgenweck’s M 875 Replica

Although M 875 is under lock and key in the Leitz Museum, that hasn’t stopped some very talented Leica collectors who have a knack for machining their own parts and making their own M 875 replica.

Such a person is Ray Morgenweck who analyzed every image of the original device he could find, and using his knowledge of other early Leicas, he recreated an exact replica from scratch. Using the measurements from Georg Mann’s May 1992 article in VIDOM 50 and the photos he took, Ray hand cut an inner wooden core and built around it an aluminum and brass shell using tools and methods consistent with what Oskar Barnack would have had access to over 100 years ago. Ray’s replica is about as close as most people will ever come to having the original, even making his own hand written M 875 label!

Photo Credits: Each of the photos of Ray’s M 875 replica were taken by me at Tamarkin Camera in Chicago, Illinois. I took this camera to visit Dan Tamarkin at his shop to see what he knew of it, and he was so impressed with it’s quality and history, that he insisted I use his shop as the backdrop for my photos.

The attention to detail in this replica is stunning. I am extremely impressed that Ray was able to make a replica of something that so little is known about just by looking at photos. In addition to the design, the amount of convincing brassing, scratches, and other signs of wear is impressive. Up close, Ray’s M 875 looks like it is over 100 years old, hand made in a work shop using all hand tools, when in reality this thing is only a couple of years old.

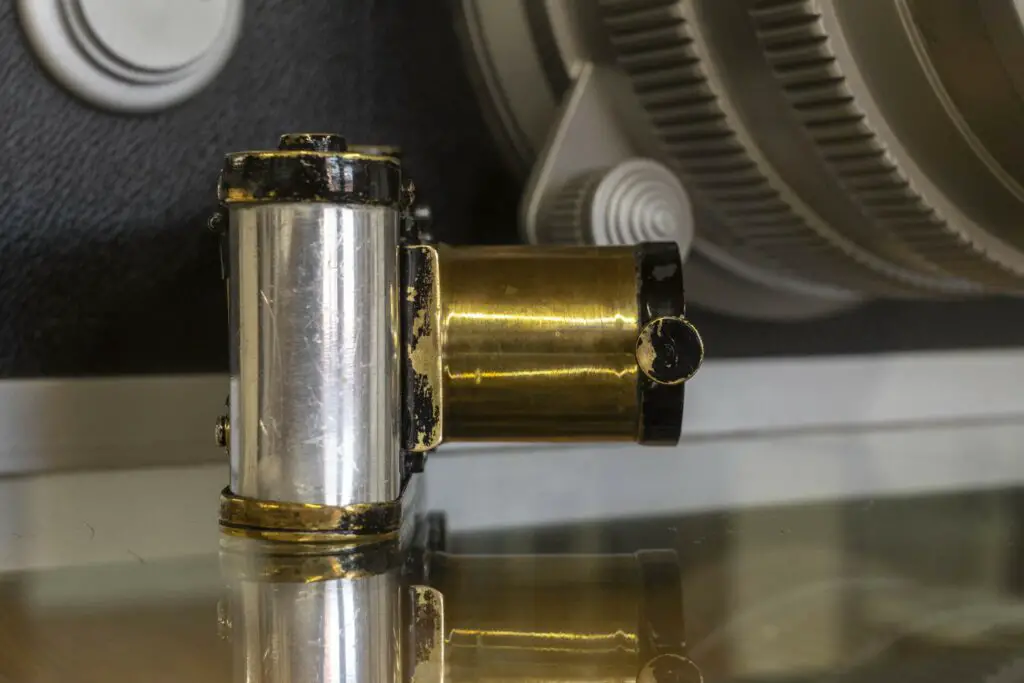

Although we believe that Barnack would have used the 5cm f/3.5 Tessar from his cinema camera, Ray took a 5cm f/2.8 Schneider Xenar from a Kodak Retina and mounted it into the barrel of his replica. There is no adjustable diaphragm, but he inserted a washer which approximates an f/8 opening to help improve depth of field and sharpness.

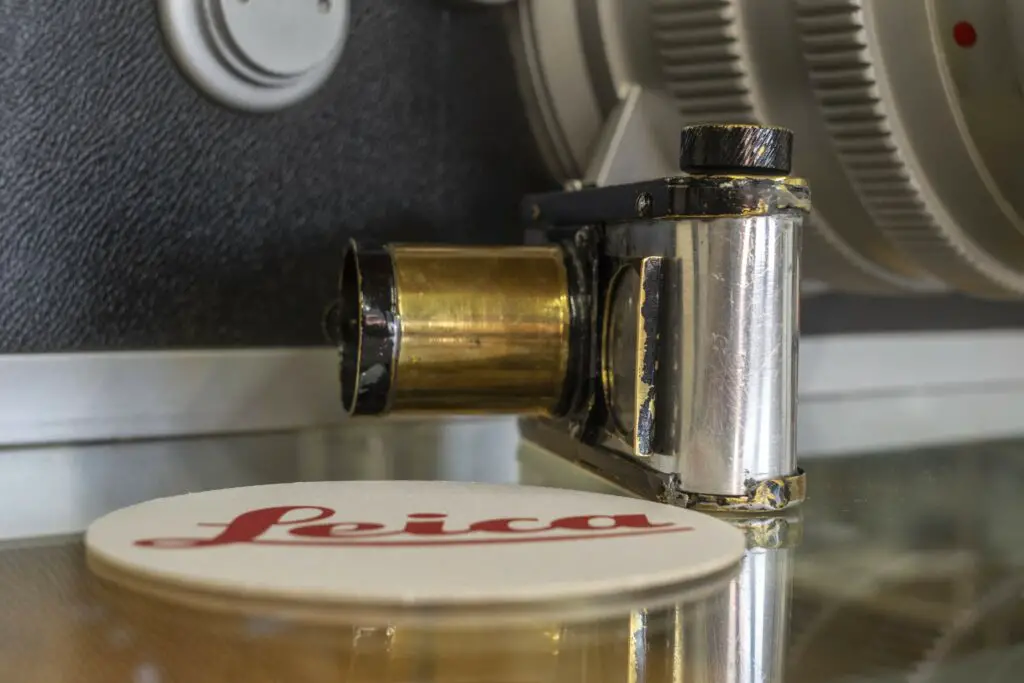

For the shutter, Ray uses the dark slide behind the hollow tube as a guillotine shutter, exactly how he believes Barnack designed it to be used. Holding the camera vertically, you can flick the slide open and closed to approximate a 1/40 second shutter speed, which is on par with what cinema cameras of the era would have shot at.

We really do not know what the intent of M 875 was supposed to be. Was it an early prototype of Barnack’s eventual Liliput Camera, or designed for something else entirely? We’ll likely never know, but one thing is for sure, the current state of M 875 is not a complete camera.

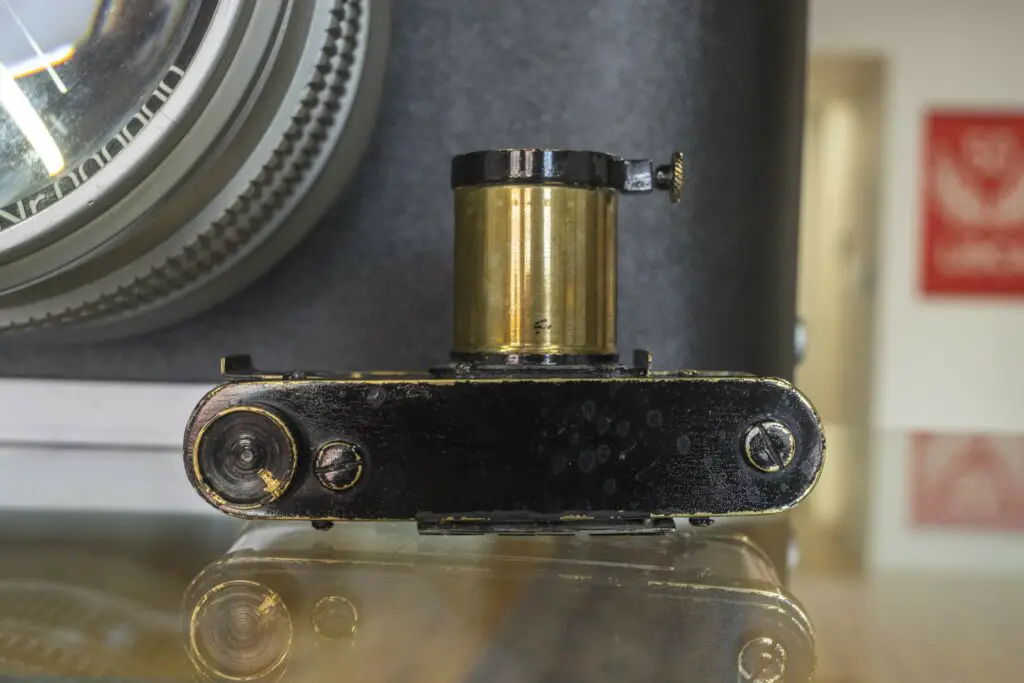

With such a simple device, it shouldn’t be a surprise to see that the camera is lacking in many of the features you’d expect to see from a “camera”. The top and bottom plates are very plain with only a film advance knob on the left and two large screws holding the body together. On this example, the wind knob has a notch in one side that is used to count how far the knob is turned when advancing the film. There is no exposure counter or any attempt to keep track of how much film you’ve used, so counting the number of turns is the only way.

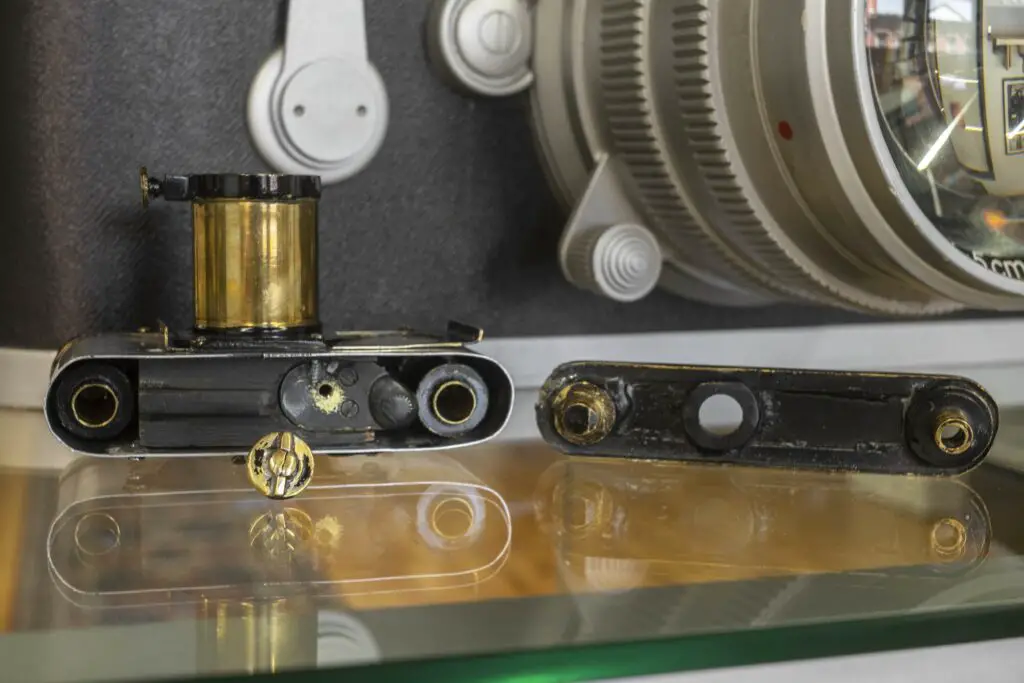

The bottom has a 3/8″ tripod socket on one side, just like you’d expect to see in a finished Leica. In the center is a knob with two “wings” on it that is threaded into a hole in the camera’s inner body. Unscrewing this knob removes the bottom plate for film loading. Unlike a finished camera, the knob does not stay attached to the bottom plate, so when it comes off, care must be taken to not lose it.

Like the other Ur-Leicas, film loads through the bottom onto two metal spools. Each side of the film compartment is too small for a reloadable or standard type 135 cassette, so film must be bulk loaded onto the spools in a dark room. A door on the back of the camera can be opened to inspect the film plane and also act as a rudimentary pressure plate, but it is hardly light tight, and Ray warned me that if I were to try and shoot it, I would need to shore up the seams with some electrical or gaffer’s tape.

With the bottom plate off, you get a good look at the wooden core of the camera’s body. In the early 20th century when the original camera was made, wood was a very commonly used material when building cameras as it was inexpensive, and easy to cut into any shape you needed. This replica holds true to that original design with an aluminum body wrapped around the inner wood core.

There is little to see on the sides. As with the later Leicas, M 875 has rounded edges and no hinge or seam for the film compartment. Although this means film loads from the bottom, it also means there is no chance of light leaks from either side of the camera. There are also no other features like strap lugs, flash sync ports, or other “camera-like” controls. A knurled knob on the side of the outer rim of the brass barrel serves no purpose on this replica, but on the original may have been used to hold a lens possibly from Barnack’s motion picture camera.

One thing I do find interesting is that the length of the barrel is much longer than that of a regular 35mm camera. Comparing M 875 to a screw mount Leica with a collapsible lens, where the lens would be on the front of the brass barrel puts it much farther away from the film plane, further suggesting that perhaps this device was intended to be used with a lens from some other camera. Ray’s use of a lens from a Kodak Retina required him to mount it further into the barrel, so that the proper flange focal distance of a Retina would be maintained.

The back of the camera is where we see a hinged brass door that opens to reveal the film plane. Unlike a more refined camera, the hinged door is held in place by two swiveling latches, the right one being much longer than the left. We do not know for sure the purpose of the round door on the back of the camera, but perhaps it was used as a sort of graphoscope similar to the Alfred C. Kemper Kombi. A graphoscope is a primitive slide viewer, in which developed images of film can be reinserted into the camera and by looking through light entering the front lens, you can see and inspect the image through the opening in the back. We may never know for sure the purpose of the round door, but it is interesting to see a foreshadowing of a very similar door re-appearing in 1953 with the release of the Leica M3.

In the bottom right corner of the back, Ray has mimicked the hand written M 875 label that is applied to the original in the Leitz museum. The original label is red however, whereas this one is white.

Lifting the hinged door, we see one of the exposure tester camera’s most unique features, which is it’s round film gate. Looking through the round hole in the metal body, we see a slightly smaller hole in the wooden body. In the original VIDOM article, it says the diameter of the opening varied between 23.2 to 23.8mm further suggesting that an attempt was made to fit an image between the rows of perforations on 35mm kine film. Although I made no attempt to measure Ray’s opening, from the naked eye, it looks pretty close to the same.

In the two images above, I show the back with the dark slide “shutter” closed and open. The sliding action of the plate is not light tight, so with film in the camera, light will constantly be leaking onto your film. All of Ray’s attempts of shooting film through his replica were done with extremely slow ASA 6 or slower film.

To make using the guillotine shutter easier to use, Ray built a custom bracket that screwed into the 3/8″ tripod hole in the bottom plate and mounted the camera to a standard tripod sideways. Since M 875 shoots circular photos, there is no difference holding the camera in portrait or landscape orientation.

I attempted to load film into the camera and mount it to my tripod using the bracket Ray included when he sent it but I kept running into problems, and this being a one of a kind replica of unknown value, I did not want to risk breaking it.

My first attempt at loading the camera ended up tearing the roll of film and I was so frustrated getting it in there, I gave up. In a second attempt, I was able to get film into the camera and the bottom plate back on, but no matter what I did, turning the advance knob would not move the film. Sadly, I have no images that I made with the camera, but Ray sent me two examples he shot. He did not specify which film he used to shoot the two images below, but he said he rated it at ASA 6, so it was probably some type of archival copy film.

Ray Morgenweck’s previous experience fabricating custom cameras made him the perfect person to take on creating an almost identical copy based solely on photos without ever having seen the original. The attention to detail is impressive and I would be willing to bet that if you showed his copy to 100 people and told him this was a ~110 year old prototype, 99 would have no problem believing you.

…and that’s it! The story of M 875 is still evolving. This is a camera that so little information exists about it, that even Leitz themselves doesn’t quite know what they have. As I learn new information about M 875, or perhaps other early Barnack works that might show up, I’ll be sure to update this article.

I Want My Own M 875 Replica: Unfortunately, Ray’s M 875 replica is a one of a kind and he has no desire to build another. If you’d like to create your own, using the images in this article and the information I’ve provided, you already know more than Ray did before he made his!

In my time writing this article, I thoroughly enjoyed the research, picking the brains of Ray Morgenweck and Dan Tamarkin, reading countless forum posts on the LHSA website, translating the German VIDOM article, and reading what little I could find in Leica history books. Thank you to everyone who helped me put this article together, and thank you to Ray for entrusting me with your one of a kind replica!

Hello Mike, This is a very nice article. I am doing research on this subject as well. It would be nice to get in touch so as to share information. Kind regards and take care, Roland Zwiers

Roland, feel free to email me using the contact form on this site.

I’m a Leicaista and am fascinated by the History behind Oskar Barnack, Leitz and Leica Cameras! Thanks for this article! I must add though, the link to Ray Morgenweck’s website is broken. Unfortunate, because I would enjoy seeing additional examples of this artist’s work

Thank you Mike for this story and the photos of the replica. I am working on a project of sorts on the Barnack Leica so this is fascinating. My hypothesis is that M875 was the actual cine film exposure tester, rather than the Ur Leicas. Functionally, M875 would have enabled various lenses to be tested at the very least for their image circle size, mounting distance from the film plane, and perhaps even exposure with the camera set in a controlled dark environment or with temporary measures to stop light leaks around the back. This would corroborate with the story, that cites the exposure tester as a separate device to the Ur Leica. It is functionally so close to a portable camera, Oskar Barnack must have been inspired by this and developed the idea into functional camera that became the Ur Leica.