This is a Gelto DIII, a collapsible lens viewfinder camera made by Tōa Kōki Seisakusho starting in 1937 and produced until at least 1952. The Gelto DIII shoots 3cm x 4cm images on 127 format roll film. A large number of variations exist for the Gelto, some with leather covered bodies, and others with silver or slightly gold finished metal bodies. Versions exist with a variety of different lenses and shutters. This model is a postwar version of the camera as it has a removable back and bottom with lever on the top plate for unlocking the back. Most prewar Geltos loaded film through the top plate with a few loading through the back, but have a completely different locking method than the postwar versions.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (sixteen 3cm x 4cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 5cm f/3.5 Grimmel Anastigmat uncoated 3-elements

Focus: 0.5 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Gelto Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1/5 – 1/250 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync, if hotshoe, flash sync speed

Other Features: None

Weight: 480 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Gelto DIII is a well built and attractive early Japanese roll film camera that was built in sufficient quantities to be relatively easy to find today. Although simple in operation, when used to it’s strengths, is a capable camera whose small size makes it very portable. A limited top shutter speed means the camera works best with slower film, but considering most options for 127 film today aren’t that fast, it’s not a huge problem. There are certainly better options out there for those wanting a compact roll film camera, but there are also many that are much worse. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.8 | ||||||

History

Usually when talking about pre World War II Japanese camera makers, names like Nikon, Canon, Minolta, and Konica come to mind. The reality is, there were many companies both before and right after the war that barely made a blip on anyone’s radar, sometimes not even making a single model that went into production. Others, like Tōa Kōki Seisakusho are somewhere in between because they made a somewhat popular model and for quite a long time.

The early days of the Japanese Photo Industry are difficult to understand, largely because of a huge number of “Camera Works” companies that all operated under a large number of vague sounding names, often masking the original manufacturer in favor of a distributor. The use of these Camera Works names started around 1910 and lasted until the early 1950s making the true identity of who made each camera almost impossible.

Further complicating history is that the Japanese economy was heavily dependent on domestic sales as Japan was not a recognized source of exported goods, especially photographic cameras so very few ever made it into the hands of Western photographers. A large number of independent camera makers existed, often changing names, merging with others, or simply going out of business over night.

In the 1930s, most Japanese cameras were copies of, or heavily inspired by designs coming out of Germany and the United States. Copies of Kodak folders and box cameras were as common as German inspired roll and sheet film cameras. In fact, it was not uncommon to find Japanese cameras with German Compur or Prontor shutters that were used instead of Japanese shutters.

Back then, film was very expensive to manufacture, sell, and develop, so small cameras were generally preferred over larger ones. Of the roll film cameras that were popular in the 1930s, many used 127 “Vest Pocket” film. Cameras like the Konishiroku Pearlette, Minolta Vest, Minion, and Ricohl all used 127 format, and in most cases shot sixteen 3cm x 4cm images per roll.

According to Sugiyama’s Guide to Japanese Camera, in 1936, a new company called Takahashi Kogaku created a new solid body 127 roll film camera called the Gelto. The Gelto had a collapsible 50mm f/4.5 Grimmel Anastigmat lens and was set in either a Gelto or Seikosha Licht 3 speed leaf shutter. A type II Gelto was also available which had a more advanced 6 speed shutter. Neither the type I or type II Geltos were identified as such on the camera.

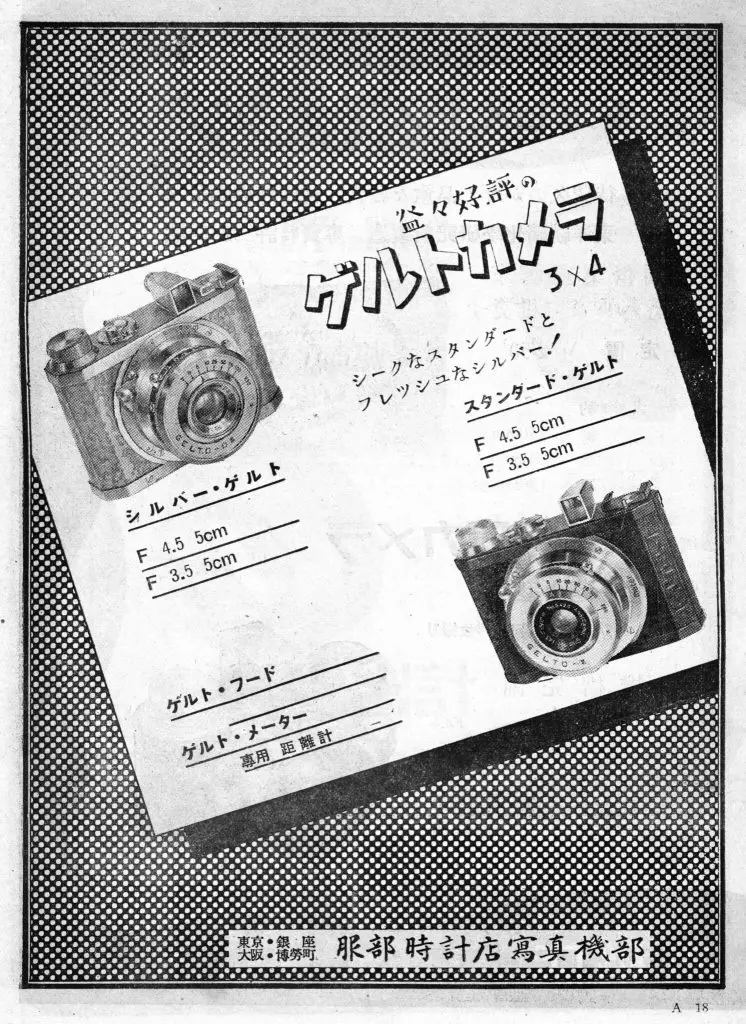

Very little is known about Takahashi Kogaku, their history, or who ran the company. What we do know is that like many Japanese makers of the era, the Gelto was distributed by Hattori Tokei-ten, a watch maker who in 1892 founded Seikōsha, maker of Seiko watches and later, of Seikohsa shutters. In addition to their camera shutter business, Hattori Tokei-ten imported Zeiss-Ikon and Certo Dolly cameras into Japan, and exported Gelto, Lord, and Zenobia cameras out of Japan.

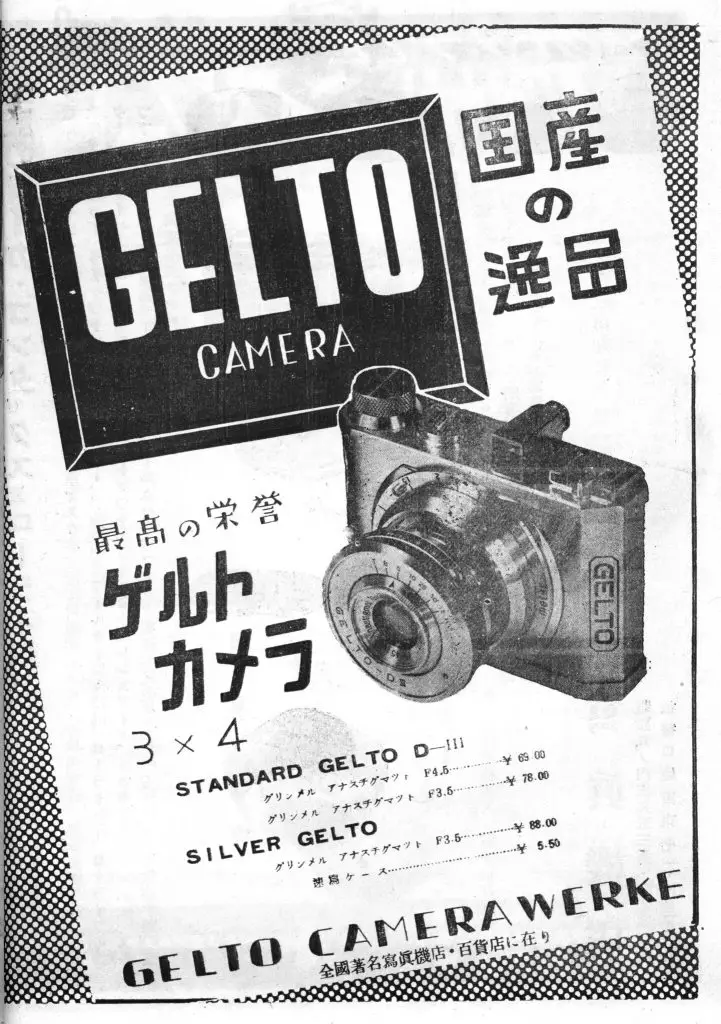

Between 1936 and 1938, Takahashi Kogaku would change it’s name to Tōa Kōki Seisakusho which in English means “Far East Optical Works”. In 1938, the Gelto III was released which improved the shutter to a faster 7 speed design, and also offered a faster f/3.5 Grimmel Anastigmat lens option. Around this same time, the Gelto D-III was released with the only new feature being the addition of sliding covers over both exposure number windows on the door. The Gelto D-III was offered in both black paint and leather and also in a textured silver body. Versions of the Gelto with a coupled rangefinder were also called the Gelto-D III but these are clearly different models.

Externally, the Gelto D-III was very similar to the earlier models and it is not clear exactly whether this was intended to be an all new model, or whether the name change from Takahashi to Tōa Kōki required it. A huge number of variations of Gelto D-III cameras were made, some with different combinations of lenses and shutters, different top plate designs, and different textures in the body covering. The Gelto page on the camera-wiki website does a pretty good job of explaining all the differences, so rather than re-type all that info here, I encourage you to check out their page if you want to know more.

Geltos with more significant changes include the uncommon Gelto S which adds an exposure counter and automatic stop film advance to the top plate. As best as I can tell, these cameras were only produced between 1940 and 1943.

In 1943 or 1944 an updated Gelto, called the New Gelto was made, which was probably intended to replace the earlier model. Until this point, all Gelto cameras loaded film through the top by removing the entire top plate and dropping the film in. This was similar to how the German made Wirgin Gewirette loaded. The New Gelto was the first version that loaded through the back with a completely removeable back and bottom plate. The New Gelto looks very similar to the regular Gelto D-III and retains the same Gelto markings on the shutter. The top plate has an engraving that clearly says “New Gelto” confirming that was it’s official name and not one applied to it by collectors. The only other identifying feature of the New Gelto is a round door lock on the bottom of the camera with O and L positions for Open and Lock.

After the war, production of the Gelto resumed, but most of the updates from the Gelto S and New Gelto were gone. Postwar models still had a removable back and bottom, similar to the New Gelto, but instead of a round lock on the bottom, used a lever on the top plate which locked and unlocked the back. As with the prewar models, there were a lot of subtle variations of the same basic formula, even some with add on rangefinders, but I’ll refer you once again back to camera-wiki’s page for that.

At some point between 1948 and 1952, Geltos were made by a company named Shinwa Seiki but it is not clear whether this was actually a new company, or just a renaming of the original company. Geltos from this era were distributed by Mizuno Shashinki-ten who also distributed a number of other Japanese cameras. The last appearance of advertisements for the Gelto were from 1952, and Mizuno appeared to go out of business in 1953, which both suggest the Gelto was no longer produced after that time.

There is no evidence that the Gelto was ever exported to the United States, so determining what it might have sold for here is difficult. In Japan, prices for the prewar Gelto ranged from ¥ 69 for the Standard Black painted model with f/4.5 lens to ¥ 88 for the Silver model with f/3.5 lens. The ad to the right from 1943 lists a version with f/3.5 lens for ¥ 117.94 and with f/4.5 lens for ¥ 103.48.

Using these prices and looking through other 1943 Japanese catalog prices, the Gelto was about half that of a Waltax Semi 4.5cm x 6cm folding camera, and roughly 3-4 times more than a Mycro “Hit” style camera. These comparisons should be taken with a grain of salt, but it’s probably safe to assume these were considered low to mid market options for amateurs, similar to what a point and shoot camera would be today.

Accurate records of serial numbers and production dates were not kept, so if you have a Gelto and want to date it, it can be difficult. Generally speaking, here are some truths that can help you narrow down your model:

- Does not say Gelto III or D-III on the shutter and loads film from the top, it is a 1936-1937 Gelto type I or II

- Says Gelto III or D-III on the shutter and loads film from the top, it is a prewar model.

- Has a stepped top plate with an exposure counter and auto stop mechanism, it is a Gelto S from 1940 – 1943

-

An early postwar design of the Gelto with a New Paragon shutter. Says New Gelto on the top plate and has a removable back with lock on the bottom, it is a New Gelto from 1943 – 1944

- Has a removable back and bottom with an Open and Lock lever on the top plate and engraved TOAKOKI on the side, it was made after the war, up to 1948

- No longer engraved TOAKOKI on the side, instead says GELTO, probably from 1948 to 1952

- Coated Grimmel C lens, very late, probably 1952

Today, the Gelto is somewhat of an anomaly as most prewar and early post war Japanese cameras are either 120 folders or 35mm rangefinders. Of the many 127 film cameras made during that era, most were produced in such small numbers, they hardly ever show up for sale today and are only collected by rich dentists. I wouldn’t quite say that the Gelto is a common camera, however they can consistently be found for sale on eBay. As I write this, a worldwide search produced 11 for sale, ranging in price from $81 to $340.

These were well made and good looking cameras, especially with the all metal bodies. Although 127 film isn’t commercially made, its one of the easier extinct formats to adapt and still shoot. With a steady hand and a clean lens, the 3cm x 4cm images these cameras make should turn out quite good, making the Gelto equally attractive to both collectors and shooters alike.

My Thoughts

Late last year I published my review for the Wirgin Gewirette, a compact collapsible lens camera that shoots 3cm x 4cm images on 127 roll film. Shortly after that, friend and site reader Roger Beal offered up a Gelto III, another compact collapsible lens camera that shoots 3cm x 4cm images on 127 roll film.

Comparing the two, the Gelto is larger in every dimension except depth and weighs considerably more. At 480 grams, the Gelto is misleadingly heavier than it’s small body would suggest. At 305 grams the Gewirette disappears in a medium to large coat pocket as it’s small size and weight aren’t nearly as noticeable as the Gelto whose weight approaches that of some 1980s electronic SLRs. Adding to the Gelto’s perceived size, it’s angular body and location of the accessory shoe near the edge of the top plate means it is more likely to snag while taking out of or returning the camera to a pocket or case. One last difference, is that although the Gelto’s gold tinted body and interesting texture are pretty, it is a bit more slippery than the Gewirette’s leather covered body.

The camera’s top plate is a bit crowded with the accessory shoe on the far left and optical viewfinder to it’s right. In the middle is a rather elaborate lever which is the film compartment release. The lever has two positions, “O” for open and “L” for lock. Finally, on the right side is the film advance lever with an engraved counterclockwise arrow indicating direction of travel. The knob is geared in a way where it will not spin clockwise.

The bottom of the camera is a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, and two feet on each side of the camera that I would normally suggest are there to stabilize the camera when set on a flat surface, except the Gelto is so front heavy, even with lens collapsed, will always fall forward resting on the bottom edge of the shutter. For display purposes, the focusing arm is just the right length to where if you position it facing directly down, it acts as a kickstand, supporting the weight of the lens. This wouldn’t be very useful for shooting with the camera on a flat surface however as with the focusing arm pointed down, the lens is focused to just under 1 meter. Long exposures with the Gelto will definitely require a tripod.

The sides of the camera are symmetrical and have no provision for any kind of strap. Rectangular plates on both sides continue the textured pattern from the front and back with the one on the left side saying “TOAKOKI SEISAKUSHO”.

Around back we see two sliders covering the twin openings for reading exposure numbers on the paper backed film. In the era this camera was made, the exposure numbers on 127 roll film did not account for 3cm x 4cm exposures. The only numbers would be numbers 1 through 8 for 6cm x 4cm. In order to count exposures on the Gelto, you must use each number twice. Since film transports from left to right, the first exposure is made when the number ‘1’ is in the left window. The second exposure is when the number ‘1’ is in the right window, the third when the number ‘2’ is in the left window, the fourth when ‘2’ is in the right window, and so on. The 16th and final exposure is made when the number ‘8’ is in the right window. Unlike more basic 3×4 cameras, the metal sliding doors protecting the red windows have their own sliding doors which can be independently opened, which is a nice touch, to minimize the amount of light that may hit the film. One last thing to see from the rear of the camera is how much taller the viewfinder is than the rest of the camera, which adds to the “snag factor” when taking this camera in and out of it’s case.

After moving the film release lever on the top plate of the camera to the “O” or open position, slide the entire back and bottom down, to reveal the film compartment. Film transports from left to right, which is a bit unusual as most 127 cameras go in the opposite direction. As with all roll film cameras, an old supply spool becomes the take up spool by moving it to the right position. A small chrome indentation on the bottom of both sides of the film compartment can be pushed down for ease of installing a spool. To the left and right of the film gate are chrome rollers to aide in film transport. The inside of the door has a polished metal film pressure plate to maintain flatness while film transports through the camera. There are no light seals of any kind on the body or the door of the camera.

Before shooting the Gelto, you must remember to extend the lens. This is done simply by pulling it forward from the body. Unlike many other collapsible lens cameras, the Gelto doesn’t have a lock which is normally achieved by slightly turning the lens after extending it. I am uncertain if other versions of the Gelto have this feature, but on the example here, the shutter and lens only go forward and back. Thankfully, the movement is pretty stiff, which helps to prevent it from accidentally being pushed back into the body while shooting which would result in grotesquely out of focus images.

Looking down upon the top of the shutter, there is a metal ring for controlling the diaphragm. F/stops from f/32 to f/3.5 are selectable from left to right. Around the front edge of the shutter is the shutter speed selector. Strangely, the shutter speeds cannot be read from above, only from the front. Speeds from 1/5 to 1/250 plus B and T are available on this version of the Gelto. Other revisions of the camera had different combinations of speeds.

While looking at the front face of the shutter, near the 1 o’clock position is the shutter cocking lever. The Gelto’s shutter is not coupled to the film transport so you must remember to cock the shutter before each exposure. Near the 11 o’clock position is the shutter release. There is no provision for double exposure prevention, so care must be taken to remember to advance the film after each exposure, unless of course you want to make double exposures. I quite liked the symmetrical location of both the shutter cocking and shutter release levers. I found this arrangement easy to locate with both my left and right index fingers while out shooting with the camera.

The entire lens and shutter are mounted to an focusing helix inside of the camera’s body. Thankfully the lube on this example had not dried up and was easy to move, although it wouldn’t be a stretch to anticipate this being a failure point on other cameras. Focus marks from 0.5 meters to infinity are on the front face of the helix and a complete motion requires approximately a 270 degree motion.

Caution: A word of warning is that the Gelto’s shutter and lens are attached to the body via a simple screw mount. If while trying to extend the lens, you give too much of a twisting action, you can unscrew the shutter from the body.

The viewfinder is a straight through optical design with glass elements in the front and back. The small size of the rear eyepiece meant that I could not see the entire image while wearing prescription glasses, although this is a minor issue as these kinds of viewfinders are usually just estimations anyway. A nice touch is that the rear eyepiece can easily be unscrewed to gain access inside the viewfinder for easy cleaning.

The Gelto DIII is certainly larger and heavier than other 3×4 cameras in my collection, not just the Gewirette. It’s increased size and heft give it a reassuring feel. Whereas cameras like the Foth Derby have hollowed out steel bodies, the Gelto is a large hunk of cast brass. Nickel and chrome plated metal pieces are all over the inside and outside of the body. Despite some claims I’ve read online about the Gelto’s being cheaply made, I don’t know that I agree. A touch less refined than German models yes, but not cheap. But how are they to shoot? Keep reading!

My Results

It would take me longer than I had originally hoped to get some sample images from the Gelto as my first roll was shot on what I thought was color film, but ended up being black and white and after developing the roll in C41 chemicals, I ended up with a roll of extremely faint exposures that I couldn’t salvage with my scanner. It would take me several months before I would try again, but this time, taking care to remember that I loaded in some bulk expired Fujicolor Pro 160 S that I hand rolled into a 127 spool, I actually developed this one correctly.

Looking past several light leaks and some discoloration in the 15 year expired color film, the images came out better than I expected. I was really impressed at the color rendition of the uncoated Grimmel Anastigmat lens as the colors were quite vibrant, at least as much as the expired Fuji film allowed.

Beyond the colors however, things started to fall apart quickly. Sharpness of the three element Grimmel was pretty decent in the center, but had significant fall off near the edges. I am not a lens anomaly expert, so I don’t always know the correct terms, but the edges and corners seemed to exhibit some type of barrel distortion as the aspect ratio seemed a little off to me. Considering this lens was designed to cover a 30mm x 40mm image which is only marginally larger than a 24mm x 36mm image from a 35mm camera, I would have assumed this lens would have had better coverage.

Beyond the issues with image quality, I can’t honestly say I loved using the Gelto DIII. With the lens extended, it does not lock into position with a twist like other collapsible lens cameras, meaning that the slightest bump can cause it to retract throwing off focus. The viewfinder was tiny and impossible to see the entire image while wearing glasses. Having the film door release in such a prominent location on the top of the camera made me nervous every time as I feared I would accidentally open the film compartment and expose the film.

What really bothered me the most about the Gelto were it’s ergonomics. To be fair, the control layout is pretty typical of cameras from this era. There aren’t many differences between the Gelto and cameras like the Wirgin Gewirette, or even the Foth Derby, both 127 roll film cameras that make 3cm x 4cm images. The issue for me, was with the slightly larger and heavier body with more angled, rather than rounded cameras, the Gelto feels like a larger and more cumbersome of a camera than it actually is. The angled corners of the body, the sharp edges of the accessory shoe and viewfinder, and the protruding cocking and shutter release levers always seemed to snag something when taking the camera out of my bag or a large pocket. I felt as though I constantly needed to keep checking the camera before using it. Again, it’s not dramatically different than other early collapsible lens cameras, but I feel that if I had access to both a Gelto and the Gewirette, I would have preferred the latter.

None of this means the Gelto is a bad camera however. I quite liked the looks of the camera and having a large sweeping focus helix as opposed to front element focus like on lesser cameras is a huge plus. I just didn’t enjoy shooting it as much as I thought I would. Maybe your experience will be different from mine, and if so, that’s okay.

My final opinion of this camera is that it is a solidly built and attractive camera from a period of Japan’s camera history that isn’t well known. Geltos aren’t exactly common, but there’s always a couple for sale at any one time online, so whether you’re just a fan of early Japanese cameras, or want something a little different, these make great additions to any collection, just don’t go out of your way to find 127 film and shoot one!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Gelto

http://floggingenglish.com/photography/gelto-diii-a-gem-among-cameras/

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/other/127_film.html#gelto

https://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/appareil-11733.html

http://asacame.fc2web.com/hspbest/gelto.htm (in Japanese)

http://otonyann.blog.fc2.com/blog-entry-418.html (in Japanese)

Mike, Would you be interested in reviewing some better 110 cameras if I lpoaned them to you with film? I use PRWO UN54 reloads… Terry