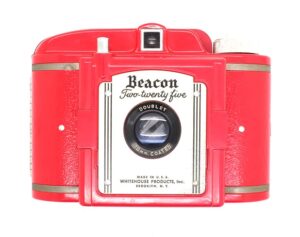

This is a Beacon Two-Twenty Five, an all-plastic medium format camera made by Whitehouse Products Inc, in Brooklyn, New York, USA between the years 1950 and 1958. It is a simple camera with a single speed shutter, fixed focus, collapsible doublet lens, and an aperture setting for Dull and Bright light. The body is made entirely of Bakelite, giving it a bit of heft, but if dropped, can be fragile. Most examples of this camera are black, but it also came in ivory, beige, turquoise, and red. Whitehouse made a variety of Beacon models, many of which used 127 roll film. This was the only model to use 620 film or make 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ images.

Film Type: 620 Roll Film (twelve 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ exposures per roll)

Lens: 70mm f/12.5 Beacon Doublet coated 2-elements in 2-groups

Focus: Fixed, ~5.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Rotary

Speeds: Instant ~1/50 and Time (Bulb)

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: None

Weight: 406 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/beacon_two-twenty-five.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Beacon Two-Twenty Five is an attractive, simple, yet capable medium format camera that despite it’s modest feature set is capable of taking pretty good images. Many American cameras of the 1950s were of this type that were inexpensive, easy to use, and made “good enough” images. A huge benefit of cameras like these is that they almost always still work great. If you find one in a closet or basement, wipe them down with a damp cloth, load in some film and experience mid-20th century photography! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.1 | ||||||

History

When it comes to inexpensive American cameras of the early to mid 20th century, a large number of brands come up, Spartus, Falcon, Universal, Utility Mfg, and Beacon. A great number of these cameras were produced either in New York or Chicago and most shot 127 or 120 roll film, but a smaller number shot 35mm film.

Nearly all of these cameras share a similar feature set, black plastic (usually Bakelite) bodies, with single or double element lenses, single shutter speeds, fixed focus, and usually limited exposure options. If the cameras offered adjustable exposure, it was not via an iris diaphragm, but rather a movable metal plate with various sized holes through it, resembling “Waterford Stops” used in large format plate cameras of the late 19th century.

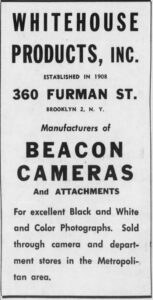

Search Google for “Beacon Camera” and you’ll easily find that these were made by Whitehouse Products, Inc in Brooklyn New York from the late 1940s to the 1960s. Dig a little deeper and you might find the company address listed as 360 Furman Street, and that they also made a rebadged Argus camera, and strangely, a fish shaped promotional camera called “Charlie the Tuna” for Starkist Tuna.

Beyond this, there is very little information online about Whitehouse, who created it, what other businesses they might have been involved in, and what became of them afterwards.

Typical Google searches and scouring the Internet Web Archive produced nothing helpful as the same one or two sentences kept showing up with the same information, over and over.

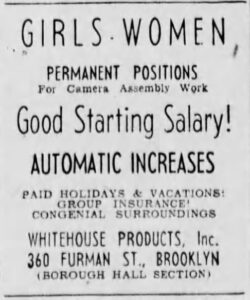

Once I directed my search towards old newspapers, I discovered a January 1954 ad for Whitehouse Products, Inc, at 360 Furman Street which suggests the company had been around since 1908.

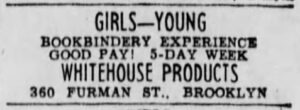

Another search for the same company resulted in a want ad from April 1946 looking for young girls with bookbindery experience. With the same name and same address, it would appear that Whitehouse didn’t just make cameras, and perhaps was also in the book publishing (or at least the book making) industry.

Further searches for Whitehouse Products in Brooklyn prior to 1946 didn’t return anything camera or optics related, further suggesting that Whitehouse was likely involved in many different industries. This is actually consistent with other inexpensive camera makers of the era as staking an entire business on the sales of cheap cameras likely wouldn’t have been profitable, so these companies often had to have their hands in other products as well.

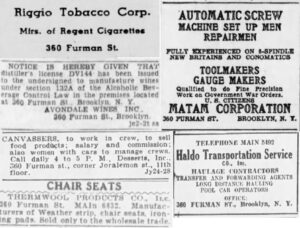

Searches for the address 360 Furman Street in Brooklyn turned up a huge number of other businesses ranging from a tobacco company, a wine company, some kind of mechanical tool maker, a food products company, a chair maker, and even a transportation service. Clearly 360 Furman Street was some type of multi-unit multi-purpose office building of which Whitehouse was merely a tenant.

It’s clear that Whitehouse was a manufacturer of a variety of goods, and worked in an office space with other companies, but what about the company itself, who founded it and what was their early history?

Going back to early 1945, I started to find ads for a company called Whitehouse Leather Products, Inc at the same 360 Furman St address. It would turn out that this link between Whitehouse Products and Whitehouse Leather Products was what I needed to go back farther into the company’s history.

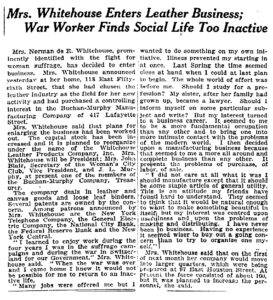

Searching for “Whitehouse Leather” produces a number of hits going back all the way to 1921. Interestingly, from at least 1921 to 1926, the President of the company was a woman named Mrs. Norman De R. Whitehouse, and in an article dated November 10, 1926 was a pioneer in facilitating a 40 hour work week among her all female employees. The article is in regards a New York law that stated a 48 hour work week which Mrs. Whitehouse was against.

Further searches about Mrs. Norman De R. Whitehouse led me to the Library of Congress who had her listed as a leader in women’s suffrage rights which eventually led to the passage of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution granting women the right to vote.

Most references to Mrs. Whitehouse from the 1910s and 20s use her husband’s name, and I struggled to find more about her previous career, but on a whim I searched Wikipedia for “Whitehouse suffrage” and found her actual name to be Vira Boarman Whitehouse, a suffragist leader who married stockbroker James Norman de Rapelye Whitehouse on April 13, 1898.

In 1918, Vira Boarman Whitehouse served Rosika Schwimmer, the Hungarian ambassador to Switzerland, who also was working to grant women’s rights to vote in her home country. Whitehouse’s work there helped cement her as not only a leader in the movement here in the United States, but also overseas.

After returning to the United States in 1921, Whitehouse would purchase the Buchan-Murphy Manufacturing Company, a leather making company and rename it to, you guessed it, Whitehouse Leather Products, Inc.

What exactly the history of Buchan-Murphy Manufacturing Company is, or whether they started in 1908, or if there was another Whitehouse company that started that year is beyond the scope of this article as I’ve already gone deep into this rabbit hole.

With so little information out there about the maker of Beacon cameras, I do feel pretty confident in saying that Vira Boarman Whitehouse, more commonly known as Mrs. Norman De R. Whitehouse was a part of that story. She was a women’s suffragist leader who dabbled in international relations and after returning home, bought her own company, in which she prominently hired women. She was an advocate of a 40 hour work week, eventually producing goods other than leather manufacturing, and eventually wound up making cameras, hiring many women to assemble them.

Whitehouse Beacon cameras first went on sale in 1946, although most sites online suggest 1947. I believe 1946 to be correct as the want ad for women to assemble cameras from November 1946 above suggests that production likely started that year. The first two models were the Beacon and Beacon II, both mostly plastic cameras that shot 3cm x 4cm images on 127 roll film. The only difference between the original Beacon and Beacon II was that the second model offered flash synchronization. Early versions of both cameras had a Bulb and Instant shutter setting, but later versions lost the Bulb setting.

![]() In 1950, a larger model called the Beacon Two-Twenty Five was released which resembled the earlier Beacon just with a larger body, shooting twelve 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ exposures on 620 format roll film. The name “Two-Twenty Five” was used to describe the 2 ¼ or 2.25 inch images the camera made.

In 1950, a larger model called the Beacon Two-Twenty Five was released which resembled the earlier Beacon just with a larger body, shooting twelve 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ exposures on 620 format roll film. The name “Two-Twenty Five” was used to describe the 2 ¼ or 2.25 inch images the camera made.

Both the Beacon II and Beacon Two-Twenty Five were on sale at the same time with both models selling for $9.95 and $14.95 respectively. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $115 and $175 respectively making them quite affordable.

Although both models are usually found in black, a characteristic of most Beacon models was that other colors were available such as red, ivory white, and teal blue.

Both the 127 and 620 Beacons were moderately successful with the Beacon II remaining in production until 1955 and the Two-Twenty Five until 1958. A third camera, called the Beacon Reflex was released that featured a twin lens design, in which a large and brilliant reflex finder allowed the photographer to compose images at waist level, while a simple taking lens beneath it exposed images to film. Unlike a true Twin Lens Reflex camera in which the viewing and taking lenses are coupled and can give an accurate image to what will be captured on film, the Beacon Reflex was simpler, more like a twin lens box camera.

Exactly what happened to Whitehouse Products throughout the 1960s is not clear. Vira Boarman Whitehouse would pass away in 1957 at the age of 82, so it is likely she stepped away from the company much sooner than that. It is possible that Whitehouse continued manufacturing goods for other companies, but in 1971 would be credited as making a strange fish shaped camera called “Charlie the Tuna” for Starkist Tuna.

It does not appear the company existed past the early 1970s as there is no other information I could find for Whitehouse Products after this time.

By the 1970s, inexpensive cameras were largely built overseas as much of the American camera industry no longer existed. That the company lasted as long as they did is remarkable considering their origins as a leather goods company.

Today, cameras like the Beacon II and Beacon Two-Twenty Five aren’t exactly collectible, but they’re common enough that they’re easy to find, especially in the United States. Although no production records of each model were produced, the ads in the collage above suggest that over 400,000 were produced between 1946 and the early 1950s. Based on the availability of models for sale on eBay the 127 Beacons are far more common than the Two-Twenty Five, but neither are rare.

For collectors, the colored versions are much more desirable as prices can sometimes exceed five to ten times that of a black model. Still, for someone looking to collect the wide number of American made cameras, there is definitely a place for these cameras. And for anyone crazy enough to want to use one, they’re simple enough that there’s little to go wrong, so in most cases these cameras are usually found in operating condition.

My Thoughts

I have a bit of a loyalty to American made cameras, not just because I am American, but rather there is a prevalent belief by many collectors that all American cameras are cheap and of poor quality and that they should not be considered worthy of being collected.

The thing about American cameras is that many simple models were built with the expectation that they made snapshots. Simple images that required little input from the user, meant to capture “slices of life” for posterity sake. Growing up in the United States and coming from a family whose photographs were taken by these cheap snapshot cameras, I look at old family photo albums and never once do I think, “Gee, it’s too bad these weren’t shot with a Leica or a Rolleiflex”. I marvel at the images from the past allowing me to remember people who are no longer with us, or from homes that we have since left, or the old station wagons that my dad used to drive.

Although Kodak made a great deal of these simple snapshot cameras, companies like Whitehouse Products made their Beacon cameras which accomplished the same thing. Simple snapshot cameras that allowed their user to make good images that captured memories with a minimal of fuss.

This Beacon Two-Twenty Five is actually my second Beacon as I once had a Beacon II which I never got along with and decided to never review, when I saw this larger and less common model, I was intrigued. It also helped that it appeared to work perfectly.

The Beacon is made mostly of black Bakelite with minimal use of metal. Weighing a total of 406 grams, the camera is not heavy, but it’s larger size required to shoot 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ comes at the expense of pocketability. The camera will still slide into a large coat pocket or medium handbag, but it certainly won’t fit into the same spaces that the smaller Beacon II might.

The Beacon Two-Twenty Five has a collapsible front, which slides in a plastic box, without the use of bellows. While this is a more rudimentary design than cameras with bellows, it has the benefit of not having to worry about pinholes. Unless it becomes physically damaged, the Beacon Two-Twenty Five should never have any sort of light leak as the black Bakelite body does a good job of keeping unwanted light out. Opening the camera is as simple as grasping the entire front plate of the camera and pulling until it locks in place. There is no front release button that you must first press. To close it, press in on two metal clamps on the sides of the box while pressing it into the main body of the camera.

Up top, there’s little to see. The top plate has a couple humps in it and rounded edges that factor into it’s styling, but apart from an aluminum film advance knob on the left, there are no other controls. If I had the optional flash module made for this camera, most of the top plate would be covered by the flash itself.

The bottom of the camera is simpler than the top, with a flat expanse of plastic and a 1/4″ metal tripod socket in the middle. The camera does offer a Bulb mode for leaving the shutter open for long exposures, so having a tripod socket was a useful inclusion.

Around back, you’ll see the round eyepiece for the viewfinder, next to it is a threaded sync port for attaching the optional Beacon flash unit, and in the center of the door a rectangular red window for reading the exposure numbers on the film’s backing paper. The Beacon lacks any sort of sliding door to protect the red window, so be sure to keep the back of the camera out of direct sunlight, especially when using a faster film.

The sides of the camera are rounded, which improves the ergonomics while holding the camera. Beyond the sliding lock for the film door on the camera’s left side, there is little to see. The Beacon lacks any sort of strap lugs which means if you wanted to carry it around your neck, either the original case or a strap that can connect to the tripod socket would be needed.

With the latch in the Open position, the right hinged film door swings open revealing the film compartment. The Beacon Two-Twenty Five uses Kodak 620 film and is incompatible with 120 film. While testing the camera, I attempted to load in a 120 spool and it physically would not fit. Some people will suggest that you can modify a plastic 120 cassette by trimming it with nail clippers or sandpaper, but I strongly recommend against doing this. The best way to shoot film in a camera like the Beacon is to hand roll 120 film into 620 spools. It is very simple to do and can be done in less than 90 seconds.

Film transports from right to left, and as with all roll film cameras, you’ll need to move the empty spool from the right to the left when loading in a new spool on the right. The Beacon is a step up from rudimentary 6×6 folding cameras, in that the film plane is flat, with a traditional metal pressure plate on the inside of the door. The pressure plate has small divots on it to reduce friction as film passes over it. On both sides of the film gate are chrome metal rollers to further aide in film transport.

One additional thing that is worth mentioning, is that when opening the film door, the viewfinder is split in half, with one glass element staying with the door and the other staying with the body. This grants you access inside of the viewfinder for easy cleaning. If you come across a Beacon Two-Twenty Five with a dirty viewfinder, simply open the back and use some Q-tips to clean it out. Finally, there are no light seals of any kind on the door or the film channels as they are deep enough to not require any.

The Beacon Two-Twenty five is designed to be easy to use so it has few controls. While looking down upon the top of the camera, on the right side of the top of the shutter plate is the chrome metal shutter release button. The shutter release is threaded for a cable release, which would be useful with the camera in Timed (Bulb) mode. The shutter release is designed in a way where it will not work unless the front of the camera is erected. This prohibits accidentally exposures while the camera is in storage.

Below and to the left and right of the lens are two sliders for exposure control. On the left is a slider for Dull and Brite. With the slider at Dull, light may pass through the lens to the film plane unobstructed, but with it set to Brite, a metal plate with a smaller hole moves in the way of the light path, effectively stopping down the lens to approximately f/16.

The slider on the right has two settings for Instant and Time. The Instant setting fires the shutter at an approximate 1/50 shutter speed, and the Time setting works exactly like Bulb in which the shutter remains open for as long as pressure remains on the shutter release. The Beacon is a fixed focus camera, so there are no controls on the lens itself.

The viewfinder is a straight through two lens optical design. The image seen through the viewfinder is has a lower magnification, making images smaller than life size to approximate the slightly wide angle 70mm focal length of the lens. Using a focal length convertor, 70mm on 6×6 compares to 38.5mm on 35mm film allowing you to fit more into the frame than would otherwise be possible with a 75mm or 80mm lens.

I mentioned above that the design of the viewfinder allows you to clean inside both viewfinder elements with the film door open. This means that any Beacon Two-Twenty Five out there no matter how dirty, should have an easy to clean viewfinder. Other than the image, there is no other information about exposure visible.

At first glance, I can see how some people might group the Beacon Two-Twenty Five into the category of bottom of the line, cheaply made, plastic roll film cameras, and while it certainly is simple, the camera has a number of nice touches like the metal front plate, adjustable exposure settings, accidental shutter release protection, metal film pressure plate, and two element lens that elevates it slightly from other bottom of the line cameras. While it wouldn’t be fair to compare the Beacon to a Voigtländer Perkeo II or the Super Fujica-Six, I definitely got the feeling the images it was going to made would be better than I expected. But did it? Keep reading…

My Results

Feeling pretty confident that the Beacon was in good operating order and knowing that I was about to take it out in the middle of December, filled with dreary winter lighting, I chose a roll of fresh Foma 200 that I had recently picked up from B&H. Knowing that the camera has a single 1/50 shutter speed but that I was going to consistently be in situations with 1-2 stops of low light, I figured the 200 speed film would still allow me to get a roll of properly exposed images.

As I opened the Paterson tank and pulled out the roll from the Beacon, I was immediately pleased to see what looks liked twelve properly exposed and in focus images. I had no doubts that the camera was making photos, but as to how good the “Doublet” lens performed, I had only skeptical optimism.

As it would turn out, the images were better than I had expected. As was the case with many American camera makers of the mid 20th century, cameras were produced with lenses that were good enough for a bulk of people who just wanted nice snapshots. That the Beacon produced large 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ images that could be printed at a decent size, or turned into super slides for projection on a large wall meant that the images had more detail than a comparably inexpensive 35mm camera of the same era would have produced.

One of the few disappointments from my first roll is that my traditional mirror selfie pic did not come out. With 200 speed film loaded in the camera, a single 1/50 shutter speed wasn’t enough to compensate for the slow f/12.5 maximum aperture. From the looks of it, would have needed another 2-3 stops of speed to get a proper exposure, but hey, at least you can see me and what camera I have!

Images exhibit excellent sharpness in the center with some obvious softening near the edges. Clearly better than a simple meniscus lens, but not quite as good as a Tessar, the 70mm doublet lens holds it’s own in image quality against many other mid-level cameras. Images with this type of softness and subtle, yet noticeable vignetting give them a very distinct, “vintage” look that many Instagrammers today would gladly use a filter for. I absolutely loved the images I got from the camera, and couldn’t wait to shoot the camera again.

Using the Beacon Two-Twenty Five was as easy as you’d expect. This is a focus free snapshot camera in which your only setting you need be mindful of is the Dull and Brite setting. With the appropriate speed film loaded, set it to Brite in sunlight, and Dull in everything else. Don’t attempt any close ups, or shots in dim light or indoors, and you’re good. I did not have one of the Beacon flashes for this camera, but had I had used one, I am certain that indoor portraits would have looked nice as well.

If there’s one thing that can elevate an “okay” camera from a great one, is the viewfinder, and although the one here is quite simple, that it’s so easy to clean means that everyone who tries to use one of these cameras should have a bright and crystal clear viewfinder, giving an accurate representation of what shooting one was like when they were new.

I won’t go as far as to say the Beacon was perfect, or that anyone reading this needs to run out right now and buy one, but if you like medium format, or square format images, and want to try a mid century American medium format camera that produces large images with good, but vintage-y image quality, the Beacon Two-Twenty Five is an excellent choice. That they can often be found for very cheap is just icing on the cake. If you find one of these at a local garage sale, or even have one already sitting on your shelf, pick it up, load in some film and shoot it. I guarantee you, you won’t hate it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Whitehouse_Products

https://alysvintagecameraalley.com/2020/07/13/the-beacon-two-twenty-five/

http://beacon225.blogspot.com/2012/01/beacon-two-twenty-five.html

https://camerashiz.wordpress.com/beacon-two-twenty-five/

https://www.photo.net/forums/topic/481803-whitehouse-beacon-two-twenty-five/

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=723 (in French)

http://historiccamera.com/cgi-bin/librarium2/pm.cgi?action=app_display&app=datasheet&app_id=2034

Thank you for the American social / political history behind this camera’s maker. That’s an overlooked component in many stories of America’s entrepreneurs.

Wishing you and your family a noisy and patriotic Fourth of July!

“That the company lasted as long as they did is remarkable considering their origins as a leather goods company.”

Interestingly enough, there are examples of other companies that started out in leather and became something radically different. Coleco, for example: Now best known for electronics (ColecoVision, the failed Adam home computer) and toys (Cabbage Patch Kids), Coleco started as a leather goods company. In fact, the name Coleco is a syllabic contraction of “Connecticut Leather Company”.

Wow, that’s something I didn’t know! Thanks for sharing! 🙂