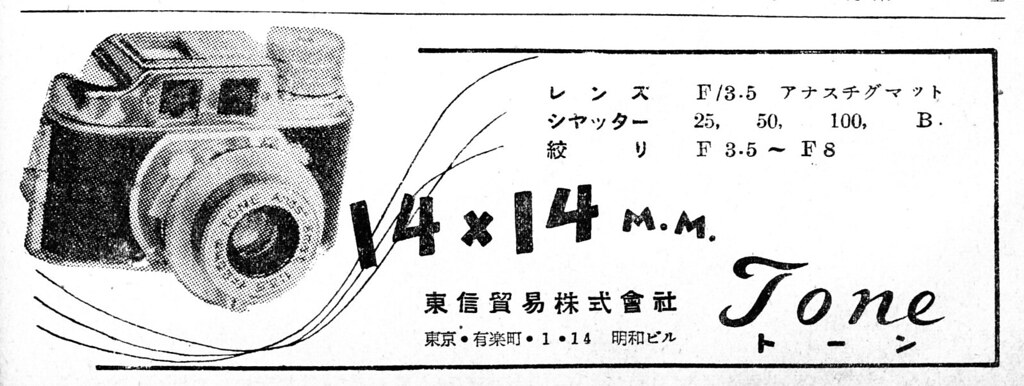

This is Toko Tone, a subminiature camera made by Tōyō Kōki Seisakusho in Tokyo, Japan starting in 1948. The Toko Tone is part of a class of cameras often called “Midget” cameras, named after a simpler model called the Misuzu Shōkai originally released in 1937. All “Midget” style cameras use special paper backed 17.5mm roll film and makes ten 14mm x 14mm exposures per roll. Unlike most models in this class of camera, which are very cheaply built with single speed shutters and fixed focus lenses, the Toko Tone is unusually advanced, with a higher build quality, a three speed shutter, adjustable diaphragm, and a full focusing lens. Many cameras of this type were sold as children’s toys or given away as promotional items, but the Toko Tone was sold as a serious camera and even at one time, exported to the United States.

Film Type: 17.5mm Roll Film (ten 14mm x 14mm exposures per roll)

Lens: 25mm f/3.5 Tone Anastigmat uncoated unknown elements

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Waist and Eye Level Scale Focus Viewfinders

Shutter: Metal Blade

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/100 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: None

Weight: 88 grams

Manual (similar model): http://www.submin.com/17.5mm/manuals/mighty/mighty1.jpg

How these ratings work |

The Tōyō Kōki Tone is one of the higher spec Japanese subminiature “Midget” style cameras ever made. It features a full focusing lens, three shutter speeds, and an adjustable diaphragm. On a technical level, this gives the camera a level of control not available on most cameras of it’s type, but that doesn’t necessarily translate into better images. I do not believe that I would have gotten significantly better images from another 17.5mm camera, but it’s still a cool, and well built example of a very popular sub-segment of camera collecting and worth adding to your collection, if only as a curiosity. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for inexplicable cool factor, although a really basic camera, it is a lot of fun to use | ||||||

| Final Score | 8.8 | ||||||

History

If someone were to ask you what was the most successful type of Japanese camera, one what was produced from the late 1930s all the way through the 1970s. A style of camera of which more than 70 major variations were produced and countless subvariants, several million made, and exported all over the world. Perhaps you’re thinking of cameras like Nikon rangefinders or SLRs, or perhaps Canon’s very popular Leica Thread Mount rangefinders, or maybe even Rolleiflex/Rolleicord style Twin Lens Reflex cameras like the Minolta Autocord or Yashica TLRs…

While each of those types of cameras are well deserving to be mentioned on lists of successful Japanese cameras, none of them are part of a style of Japanese camera that was produced more than other.

That distinction goes to Japanese subminiature cameras that use 17.5mm paper backed film. Often called “Midget” or “Hit” cameras, named after two common examples of the style, but also generically referred to as toy or spy cameras, the broad category of the Japanese “Midget” camera that uses 17.5mm film was produced longer and in higher numbers than any other style of Japanese camera.

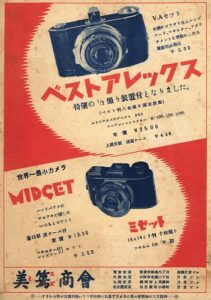

The origins of these tiny Japanese cameras start with the Midget Jilona I, a very small camera made of stamped metal with a single speed shutter, fixed aperture, and fixed focus. Credit for the design of the Midget goes to Nakamura Jirō who founded a small Japanese factory called Jilona Shōkai.

The Midget used paper backed 17.5mm film which was sourced from unperforated 35mm film cut in half and produced square images 14mm x 14mm in size. Prior to the Midget, the only two camera of similar size were the Uyeda Moment and Star Watch Camera, both pocket watch style cameras inspired by the American made Expo Watch Camera.

Although made by Jilona Shōkai, the cameras were distributed and sold by the Japanese distributor Misuzu Shōkai or Misuzu Trading Company. The camera debuted in the spring of 1937 and initially sold for ¥10 with each roll of film costing ¥2.50. Ads for the Midget later in that year show the price at ¥13.50. The inexpensive price and cheap build quality meant that the camera was likely sold as a toy or entry level photographic camera for someone who couldn’t afford more. Misuzu exclusively distributed in Japan, and it is unlikely that any of these cameras were exported out of the country.

Although made by Jilona Shōkai, the cameras were distributed and sold by the Japanese distributor Misuzu Shōkai or Misuzu Trading Company. The camera debuted in the spring of 1937 and initially sold for ¥10 with each roll of film costing ¥2.50. Ads for the Midget later in that year show the price at ¥13.50. The inexpensive price and cheap build quality meant that the camera was likely sold as a toy or entry level photographic camera for someone who couldn’t afford more. Misuzu exclusively distributed in Japan, and it is unlikely that any of these cameras were exported out of the country.

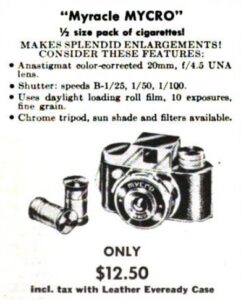

Very little information exists about the popularity of the camera, but with Japan’s weak economy at the time, and the fact that within a year of the Midget’s release, two competitors called the Mycro and Guzzi appeared, suggests that the camera was selling well. As was the case with nearly every Japanese product, World War II disrupted manufacturing of non essential products, so by 1940, cameras like the Midget disappeared from the market.

After the war, with both Japan’s economy and infrastructure in ruin, US occupation forces looked for ways to bring money into Japan by selling Japanese made goods. The simple design and ease of producing cheap cameras like the Midget and Mycro made them easy product to produce and sell.

Between 1947 and 1950, a huge number of “Midget” style camera, including a new version of the Midget called the Midget II and III entered production. Companies rose out of the ashes from other companies, some appeared overnight in small factories employing a small handful of people, even makers of other products like watches and cigarette lighters, all produced their version of a Japanese subminiature camera using 17.5mm film. This industry of cheap toy cameras was so popular, that the style of film they used was often referred to as Midget film.

Although popular in Japan, this segment of submini cameras would hit full stride in 1948 when multiple US distributors caught on to the Mycro camera and similar models made by Sugaya, Sanwa, Toko Photo Works, Tougodo, and many others. Ads for models like the Mycro and the Tougodo Hit appeared non photo magazines like Boy’s Life, LIFE Magazine, and Popular Science. Selling for as little as $9.95, the cameras appealed to children and amateur photographers.

Spy Cameras? Over the years, many of the Japanese Mycro and Hit style cameras have been miscategorized as spy cameras, and although their very small size would be an asset in clandestine photography, the cameras are of far too low of quality and the images they make are so poor that they would not be useful to actual spies. While I am certain many children pretended to be their own version of James Bond with their Hit cameras, these most certainly should never been considered “spy cameras”.

A huge majority of Midget or Mycro style cameras were extremely cheaply built with thin stamped metal bodies, primitive viewfinders, and no control over exposure, but a few more ambitious models were produced. A couple examples were the Shōwa Kōgaku Seiki Gemflex, a subminiature Twin Lens Reflex camera that used the same 17.5mm film but offered multiple shutter speeds, selectable f/stops, and a full focus lens with reflex viewfinder, the Konishiroku Snappy, a premium Midget style camera with an interchangeable lens mount, full focusing lens, and multiple shutter speeds, and the Toko Tone.

The Tone camera was made by Tōyō Kōki Seisakusho and was first produced in either late 1948 or early 1949 and was initially offered in Japanese magazines, but was later exported to the United States. It had a body resembling the size and shape of the cheaper Midget and Mycro cameras, but had a higher build quality, both an eye level and reflex viewfinder, a full focusing lens, three speed shutter, and adjustable diaphragm.

The Tone camera was made by Tōyō Kōki Seisakusho and was first produced in either late 1948 or early 1949 and was initially offered in Japanese magazines, but was later exported to the United States. It had a body resembling the size and shape of the cheaper Midget and Mycro cameras, but had a higher build quality, both an eye level and reflex viewfinder, a full focusing lens, three speed shutter, and adjustable diaphragm.

The Toko (short for ‘Tōyō Kōki’) Tone was imported into the United States by a variety of distributors including Spiratone and a Louisville, Kentucky retailer called “Good Housekeeping Shoppe”. When sold by Good Housekeeping Shoppe, the Tone had a retail price of $9.95 which less than what other US retailers were selling the cheaper Mycro for. This price, when adjusted for inflation, compares to about $120 today, certainly affordable by anyone looking for an entry level camera. A Good Hosekeeping Shoppe receipt showing the purchase of a Tone camera plus postage from August 1949 is included in the gallery below.

I could not find any contemporary reviews for the Tone as it was not common for proper photographic magazines to take notice of the camera, but a short 2 page article in the June 20, 1949 issue of LIFE Magazine previews the world of Tiny Cameras, including subminiature models like the Petal, Mycro, and Rubina. Although the article is very short, it no doubt helped fuel interest in this new segment of cameras.

With such little historical documentation regarding these cameras or how long they were produced, I cannot say with any level of certainty for how long cameras like the Toko Tone were in production. One of the more popular cameras imported to the US was the Tougodo Hit and according to camera-wiki, these cameras were produced “at least through the 1970s”. For how long, or exactly how many were made is unclear, but it’s safe to assume that the answers to those questions are “long, and many”.

Since a huge number of these cameras were regarded as toys and used for non photographic purposes such as Christmas tree ornaments, it is certain that a huge number of these cameras were destroyed and discarded. For the more common models like the Mycro and Hit, they can still be found for sale online, usually in mint, unused condition, but for the less common models like the Gemflex or the interchangeable lens Konishiroku Snappy, prices can reach into the several hundreds of dollars.

Today, there are collectors who specifically seek out subminiature cameras for their variety, curious design, and that unlike regular cameras, take up far less space to display. I have personally seen collections of micro cameras like the Toko Tone that filled up an entire display case without a single duplicate. If collecting toy cameras is something that interest you, be forewarned that the rabbit hole is quite deep!

My Thoughts

Holy bleep!

Those are the two words I assume everyone says the first time they’ve seen or held a Toko Tone or any of the many “Hit Style” cameras. Often described online as spy or toy cameras, this broad classification is definitely not correct. Certainly, toy-like is correct, but despite it’s incredibly small size, the Toko Tone and the earliest cameras that used 17.5mm film like the Mycro were meant to be real cameras.

Even after looking at photos, it is hard to prepare yourself for how small the camera is. Compared to a 35mm cassette of film, the Tone is wider and taller, but only barely. The entire camera fits within the exposed image size of a Zeiss-Ikon Nettar or Zenobia C camera. It is small enough to fit inside that little coin pocket within the front pocket of a men’s pair of jeans. At a weight of 88 grams, it is not only the lightest camera I’ve ever handled, but it is lighter than the 250mL Pyrex beaker I use to mix developer when developing my film.

The small size of the camera is impressive, even more is that this is a fully functional camera with a lens that focuses from 3 feet to infinity, it has three shutter speeds plus Bulb, a diaphragm with f/stops from f/3.5 to f/11, and two viewfinders! For such a small camera to have so many controls, you have to assume the controls are even smaller, and if you made that assumption, you’d be correct.

The example I had came with it’s original leather ever ready case, which not only was still in remarkably good condition, but was of surprisingly good quality. I am no leather expert, but the leather used here appears to be of similar quality as leather cases from other Japanese cameras of the era.

Starting from the left, the top plate has the film advance knob which is quite small, but takes up about a third of the entire top plate. The 17.5mm paper back film used in the Tone is a roll film that only transports one direction, so there is no way to rewind the film. Next is a hump containing both viewfinders. An engraving with the words “Tone Pat. Toko” is next to the square reflex viewfinder. The reflex viewfinder is not coupled to the lens so it does not show focus like a TLR would, and requires your eye to be at least a couple inches away from the camera to use.

Flip the camera over and there is nothing on the base of the camera. As mentioned earlier, you cannot rewind the film, so there is no need for a rewind button and although the shutter does have a Bulb mode, there is no tripod socket or any way to mount the camera to one. On any other camera, a Bulb mode without a tripod socket would be a pretty big miss, but for a camera this small, it would probably look pretty hilarious to see this camera atop a tripod.

The sides of the camera lack any strap lugs, which like the absent 1/4″ tripod socket, would look pretty ridiculous to see a camera this small dangling from some kind of neck strap. The only thing to see on the sides is on door release latch on the camera’s right side.

The back has a very tiny round eyepiece for the viewfinder, a round yellow window for reading exposure numbers on the film backing paper, a sliding latch to protect the window from excess light, and imprinted into the body covering the words “Made in Occupied Japan”.

Swinging open the left hinged rear door reveals the very tiny film compartment. Resembling a larger 127 or 120 roll film compartment, film transports from right to left onto removable metal spools. Like most medium format cameras, an old supply spool must be moved from the right supply side to the left take up side before loading in a new roll of film. The style of film used for this camera is paper backed, so to load it, you must stretch the paper leader across the film plane and attach it to a slit in the center of the spool. Once the paper is attached and you’ve wrapped it around itself a couple of times, you can close the film door and lock the latch. Turn the advance knob until the number ‘1’ appears in the round window on the back of the camera. The film compartment lacks any sort of light seals, which it definitely could have benefitted from as these cameras are very prone to leakage, but I guess that’s part of it’s appeal.

Looking down at the top of the lens and shutter, from left to right is the shutter cocking lever, shutter speed lever, and shutter release lever. The Toko Tone lacks any sort of double image prevention so you may cock and fire the shutter as many times in a row as you wish without ever advancing the film. This makes accidental double exposures very easy, but it also makes intentional double exposures easy, depending on what you’re trying to do. The shutter speed lever has recesses at each of the three speeds plus Bulb making choosing a speed very easy. Finally, the throw of the shutter release is moderate and easy to do with your right index finger. There is no provision for a cable release, not that you’d need one.

Not seen from the top of the shutter, but on the bottom, is the aperture control with engraved markings from f/3.5 to f/11. Unlike the shutter speed lever, the aperture lever has no recesses, so it moves smoothly, allowing for in between selections to be used.

Looking at the front of the lens, the entire front lens rotates in an almost complete 360 degree circle from minimum to infinity focus. Although the nearest focus distance of 3 feet is engraved into the ring, the lens rotates quite a bit beyond that, suggesting focus distances of probably around 30 inches is likely possible. In use, the depth of field covered by the tiny 25mm lens is pretty wide, so selecting a precise focus distance isn’t really necessary. The three indicated distances of 3, 10, and infinity should be considered the same as “Closeup”, “Group”, and “Landscape”.

Both of the eye and waist level viewfinders are predictably small, but bright enough that they still give you a vague idea of what you are pointing your camera at. When composing images on the Tone, it’s best not to attempt any tight images. If you’re shooting an image of a person, be sure to give them plenty of headroom and space to the sides as there’s no telling exactly what you’ll get on film. When shooting the camera, it’s best to just consider anything you see through the two viewfinders to be an approximation and hope for the best. In fact, if you wanted to just point the camera at something and press the shutter release without even using the viewfinder, you’d probably have the same chances of getting what you want.

It takes quite a while after handling the Toko Tone to fully absorb it all. Even now as I write this, months after I first picked up the camera, I still cannot decide what kind of camera it is. The thing is so small and so many compromises are made to use it, yet it has everything a real camera should have. It is clear that whoever built this camera thought to themselves that given the restraints of 17.5mm film, he or she wanted to make the best possible camera they could. And they did, but even though this has everything a serious camera needs to make good pictures, it is still laughably small. No serious photographer in their right mind would use this to make anything but novelty photos, or would they? Keep reading…

My Results

For all of the different film formats that were made throughout the 20th century, a good number of them are still available. Less common films like 127, 828, and 110 can still be bought from boutique sellers who hand cut larger films like 120 down to smaller size and reuse or 3D print new spools. For 17.5mm film, film is still available, however you have to get creative. The most common source of film are of the hand cut variety. Clever people who have found ways to make homemade jibs that can slice film down to any size they want in total darkness.

One such clever person is Ray Morgenweck who was the man behind the replica of Oskar Barnack’s First Leica. As it turns out, Ray is adpet at more than recreating ancient prototype cameras from black and white photos, he can also make any film size he wants, so for my first ever test of the Toko Tone, he cut down some expired film he had, paired it with some historically correct backing paper, and rolled it into repurposed 17.5mm spools. He sent me the film without telling me what it was, but said it should expose at about ASA 100. Using my vast experience with Kodak TMax, I shot the Toko Tone as if it had that film in it.

My first look at the images from the Tone was a mixed bag. On one hand, I was elated to get anything at all. This incredibly tiny camera with finnicky hand rolled film sent to me by a site reader couldn’t possibly make good images could it? When I saw the images on the film, many had light leaks. In fact, I shot a total of four rolls of film in this camera and more than half of my images were completely unusable. Thankfully, when Ray sent me the new film to shoot, he also included some developed rolls he shot and looking at his rolls, he had the same challenges with light leaks as I did. I ended up scanning the best of the images I shot, plus some of his. Both shot on two different Toko Tones.

It is difficult to come up with anything meaningful to describe the image quality from the Tone Anastigmat 25mm f/3.5 lens as the images are so tiny and the film so grainy, that details are difficult to see. Like most simple lenses, the image quality in the center seems pretty good. There is decent enough sharpness in these images to where portraits should reveal enough detail in faces of your subject, and even moderate size text should be legible.

Softness and vignetting near the edges is very strong, especially at smaller apertures. I noticed that in most of the outdoor images in the gallery where the sun would have been present, the corners are almost entirely black, giving the images a rounded look as if you were shooting through a circular hole. Images like the mirror selfies and the darker outdoor scenes where the diaphragm would have been wide open, don’t show the vignetting nearly as strong.

In the Tone’s defense, the film that was cut down for my sample images was of unknown age and type. I suspect that fresh film purposely made for these cameras when it was new could have performed better.

Image quality aside, shooting the camera was not the easiest thing to do. I certainly expected there to be some compromises due to the camera’s incredibly small size, but what I didn’t expect was how difficult everything else would be.

Things got challenging from the very first step of loading film into the camera. My fingers fumbled with inserting the narrow backing paper into the narrower slit in the take up spool. Although the process was fundamentally no different than any other medium format roll film camera, everything was much smaller. My fingers fumbled keeping both spools in the camera without one side wanting to fall out before I had a chance to close the door. I was also concerned with light damaging the film as I loaded it, so I did it in as little light as I could to minimize any change that the film would become fogged before I shot a single image.

When I was done shooting, there was no hope I’d be able to find anyone local to develop the film so I did it myself, except I don’t have any spools specifically made for 17.5mm film. I do have a couple stainless 16mm spools that I thought I would try and although the film did fit, that extra 1.5mm caused it to bunch up on the spools often. Loading slightly too large film on 16mm film spools I rarely use in complete darkness was definitely not fun.

Even after developing the film and seeing my images for the first time, I was not out of the woods yet as I had to get them into my computer somehow. If you thought finding 17.5mm spools for developing was difficult, wait until you try to scan 17.5mm film. To my knowledge, no company makes a flatbed film holder for this film size, so I had to resort to sandwiching the film between two pieces of glass, and laying them directly onto the bed of my Epson scanner. I’ve used this method before with 127 and 828 film and also with other super curly film stocks that wont lay in a regular film loader, but the scanner could not detect the tiny thumbnail images, so I had to manually select each image and try to come up with scan settings that didn’t blow out the details.

Once I had the images on my screen, I guess they looked okay. This is the first camera of this type I’ve ever shot, so I don’t have any other apples to apples comparison, but looking at images from other small cameras, like 110 Pocket Instamatics and the Tessina L, the quality of the images are certainly lower, but not by a whole lot. Although I’ve spent a lot of time in this article talking about how much more advanced this camera is compared to other “Midget” style Japanese subminis, I am not certain it really translates into significantly better images. If my examples above are the best an “advanced Midget” camera can do, I can’t imagine that a simpler Mycro or Hit camera looks all that much worse.

The one thing that impressed/shocked me the most is that these cameras were extremely popular from the late 1930s through the 1960s, maybe even later. Millions of similar Mycro style cameras were made in Japan and while I am sure many were sold as toys, I believe that a lot were used. Film was extremely expensive in mid-century Japan, so the need for small cameras like this came out of economic necessity. While I am sure with some repetition and better film, some of my challenges could have been avoided, shooting the camera, developing the film, and the extreme vignetting likely happened to the original owners of these cameras, yet they kept using them!

If I’m being perfectly honest, the appeal of these cameras isn’t in shooting them today. I imagine that a huge majority of people who collect Japanese subminiature cameras never shoot them. The difficulty in obtaining film, loading, shooting, developing, and scanning is going to put off all but the most dedicated masochists. That I was able to not only shoot mine, but also capture a couple of my signature mirror selfies is imminently cool, and I am glad I was able to do it.

Now that I’ve done it however, I can assure you, I will have no desire to ever do it again. If you have a couple of these cameras and want to follow in my footsteps (or perhaps you already have), good luck! It is a fun and rewarding process, but just don’t get your hopes up too high!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

links

http://www.submin.com/17.5mm/collection/tone/tone.htm

https://www.tiktok.com/@expiredfilmclub/video/7230934799601421594

Amazing images, very Edwardian-era. Many look to have been printed from glass negatives shot with a meniscus lens in 1890.

Now, Mike, tell us why the > other < name for these cameras is “Hit”.

The photos look just like they were daguerreotypes.

Very, very tiny daguerreotypes! 🙂

Nice! Those are better shots than I would have expected! (I am a fan of grain and vignetting.)

I have one Hit camera, and I still plan to try to shoot it. I’m going to make things a little easier on myself and use 16mm film in some old backing paper. I have a feeling that the 1.5mm difference won’t change the quality of the shots that much, and this way I’ll be able to use my 110 developing reels and film holder for scanning.

Good luck with yours! I was able to develop 17.5mm film on a 16mm reel that I use for 110 film. It didnt fit perfectly, but well enough that it worked! Good luck!