This is a Samoca 35 III, a 35mm viewfinder camera made by Sanei Sangyō K.K. in Japan starting in 1955. The Samoca 35 III was part of a long running Samoca family of cameras made from 1952 to about 1961. All Samoca cameras were simple. but well built mid-level cameras with just enough features to allow for good photography, without the complexity of more advanced models. The Samoca 35 III shares the same body, viewfinder and lens as the two models before it, but upgrades the flash sync port, adds an accessory shoe, and an engraved depth of field scale on the front plate. It uses a simple two blade three speed shutter, and has a 50mm f/3.5 triplet lens. Later models in the Samoca series would add a rangefinder, more advanced shutters, faster f/2.8 lenses, a new body, and one model, would add a waist level finder, making it a twin lens reflex camera.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 C. Ezumar Anastigmat coated 3-elements in 2-groups

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical

Shutter: Twin Blade Vario Type Behind the Lens

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/100 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: None

Weight: 454 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/samoca_35_iii.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Samoca 35 III is an interesting mid-level camera that is neither cheap, nor high end. It has good build quality, a good lens, a capable viewfinder, and a serviceable viewfinder. It is a simple camera with just enough features to allow you to make great photos. Its compact size means it fits into smaller spaces making it easier to carry. Despite a small size, the ergonomics are not cramped, as using the camera for long shooting sessions is a snap. These are easily found online for a cheap price, and assuming you can get one in good condition, is a worthy addition to any collection. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.1 | ||||||

History

The 1950s was an exciting time for the Japanese photo industry. In the immediate years after World War II, Japan’s economy and infrastructure were decimated. Utilities like electricity and natural gas were in short supply, as were raw materials needed for all manner of industry.

In charge of overseeing the rebuilding of Japan’s economy was General Douglas MacArthur and the office of Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, or SCAP for short.

SCAP oversaw a large number of aspects of the Japanese rebuild, including the drafting of a new Japanese constitution, the creation of a welfare system, overseeing Japan’s first democratic election in 1946, land reform including the creation of new agricultural and commercial sectors, plus raw material allocation. To accomplish many of the ambitious projects associated with this, MacArthur knew that he needed to find a way to inject money into Japan’s economy quickly. Immediately after the war, companies petitioned SCAP to start or resume building of goods and products to be sold for export.

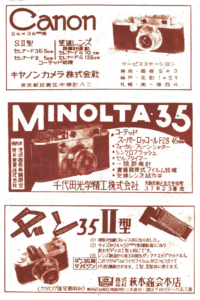

One of the early successes of this program was the photographic industry. As it would turn out, Japan was pretty adept at making cameras and lenses, having been led by Japan’s official optical company, Nippon Kogaku before and during the war. Between the years 1946 and 1948, a large number of other companies like Fuji, Mamiya, Canon, and Minolta quickly started churning out cameras, lenses, and other types of photographic equipment.

At the time, western photographers from Europe and the United States were leery of buying Japanese goods as they were seen as inferior to similar products being made in Germany. Working in Japan’s favor was that Germany was also experiencing turmoil from their role in the war, and with extremely high tariffs and trade restrictions levied on German products, many photographers started to look elsewhere for quality cameras and lenses.

In a chance encounter in June 1950 at Life Magazine headquarters, famous American photographer David Douglas Duncan was introduced to Nippon Kogaku Nikkor lenses, and after taking a tour of the Tokyo plant where they were made, Douglas started using Nikkor lenses exclusively. The outbreak of the Korean War a few weeks later led to a huge amount of exposure to Douglas’s photographs, and upon learning that the wartime images coming out of Korea were shot using Japanese optics, Japan’s photo industry was officially on everyone’s radar.

In a chance encounter in June 1950 at Life Magazine headquarters, famous American photographer David Douglas Duncan was introduced to Nippon Kogaku Nikkor lenses, and after taking a tour of the Tokyo plant where they were made, Douglas started using Nikkor lenses exclusively. The outbreak of the Korean War a few weeks later led to a huge amount of exposure to Douglas’s photographs, and upon learning that the wartime images coming out of Korea were shot using Japanese optics, Japan’s photo industry was officially on everyone’s radar.

Within the next couple of years, Japan’s optics industry went from an afterthought to competing with the Germans as Nikon and Canon rangefinders, Mamiya folders, and Minolta TLRs performed similarly, or in some cases outperformed the German competition, but at a lower cost.

To meet the huge demand of Japanese photo products, a large number of new companies were created almost overnight. A quick count of Japanese optical companies in the index of Koichi Sugiyama’s, “The Collector’s Guide to Japanese Cameras” I stopped counting at 100.

One of these new companies was Sanei Sangyō K.K. which in 1952 would release a new camera called the Samoca. Sadly, like many of these smaller companies, very little is known about the origins of the company, who created it, what they might have done before, and what they did after. One of the few known facts about the early Sanei Sangyō was that their products were heavily advertised by the Japanese retailer, Hattori Tokei-ten which was the predecessor of Seiko. Whether or not Seiko, or its parent company had any ownership or investment in Sanei Sangyō is unclear, but there was at least a connection.

As best as I can tell, the company did not exist prior to 1952 but based on similar histories of many other Japanese companies from this era, it is possible that someone responsible for the company likely had prior optical experience from another Japanese company.

Fun Fact: Several sites online suggest that Sanei translates to “three a’s” in English, which matches the logo found on Samoca cameras with three capital letter A’s in a triangle pattern. The spelling of Sanei Sangyō K.K. in Japanese is 三栄産業㈱, of which the first symbol 三 means ‘three’. Whether the rest of the explanation really means “three A’s” is anyone’s guess.

The original Samoca was a compact scale focus camera with a simple twin blade three speed shutter and a 50mm f/3.5 coated Ezumar triplet lens. Between 1952 to 1955, four different versions of the Samoca were made, all sharing the same body and lens. The differences between the four model are minor, but are:

- Samoca 35 – Original model, two blade, three speed Vario shutter, axial style flash connector, no accessory shoe

- Samoca 35 II – Same shutter and lens, new Kodak style flash connector and added accessory shoe

- Samoca 35 III – Same shutter, lens, flash connector, and accessory shoe, redesigned focusing lever and new engraved depth of field scale

- Samoca 35 IV – New Prontor style 5-speed shutter, otherwise same as previous model.

In 1955, a fifth Samoca 35 would debut with a new top plate and larger overall body, redesigned depth of field scale, and larger viewfinder. It would also lose the separate shutter cocking lever and unlike the previous models, would just be known as Samoca 35, instead of Samoca 35 V or anything indicating it was the fifth model.

Around this time, Sanei Sangyō K.K. would rename itself to Samoca Camera Co., Ltd. likely to associate itself with the camera it sold. I also believe this to be the time that Samoca cameras began to be exported to the United States. Although it is possible earlier models were exported to the US, I have not found any advertisements or mentions in any major American photographic publications.

The ad to the right from February 1957 for Brockway Camera Corporation in New York City shows the rangefinder equipped Super Samoca 35 with a retail price of $29.95. When adjusted for inflation, this price compares to about $325 today, making it quite an affordable camera. Had the earlier Samoca models been sold here, they likely would have been offered for slightly less.

The text in the ad suggests that the Samoca was new to America, but not American GIs, further claiming that over 100,000 had been sold to American servicemen and women. While this may be a boisterous marketing claim, there is some truth that cameras would have been very popular for the American military through the various Post Exchanges in which foreign goods could be purchased at lower prices, and not have to pay import taxes when bringing them home. Whether or not 100,000 Samoca 35s had actually been sold to American GIs, is anyone’s guess.

I could not find any contemporary reviews of the Samoca as its target audience was likely outside of the readership of photography related magazines such as Popular and Modern Photography. Its low price and good value, likely won over quite a few budget conscious buyers. A large number of variations of the Samoca were made over the next few years, including a strange looking twin lens reflex version called the Samocaflex and Samocaflex II.

Samoca would continue releasing new and relatively simple 35mm scale focus and rangefinder cameras until about 1962 when the company seemed to disappear. Most sites online suggest the last models like the Samoca MR and Samoca 35 LE-II ended production around that time.

There is evidence that Sanei Sangyō continued on into other industries as a Google search of that name returns a company with the exact same name who was said to have been founded in 1961. Whether this is the same company, or another with the same exact name is unclear.

In the mid to late 1970s, the Samoca name would be used once again on two cameras called the Samoca Winderflash EE and Winderflash EES. Both models were cheap all plastic automatic point and shoot cameras made in Hong Kong by Haking. According to camera-wiki, the Samoca Winderflash EE is a rebadged Halina MW35E.

Today, the market for the lesser known Japanese cameras is strong, but inconsistent. Some collectors build their entire collections around the rarest Japanese cameras, but often ignore common, but less desirable brands like Samoca. That these cameras aren’t as highly sought after like Canon and Nikon rangefinders, but aren’t as quirky as many other Japanese cameras, causes them to be in this middle range where collectors ignore them because they’re not rare enough, and users ignore them because they’re not good enough. The good news for anyone reading this article however, is that if you want to add one to your collection (and you should), prices on them are still very reasonable, and they’re common enough to easily find on eBay at a moment’s notice.

My Thoughts

Samoc ’em if you got ’em, they say! These days if you told someone you were looking for a Samoca, they would be just as likely to think you meant a vape pen as you might a camera. The reality is, that in the mid 20th century, Samoca was a line of cameras produced in Japan by Sanei Sangyō K.K. who later changed their name to Samoca Camera Co., Ltd. in 1955, right around the time the Samoca 35 III was released.

In my time perusing camera auction sites, Samoca cameras came up quite often. Having experienced the best, and “not so best” of what the Japanese camera industry had to offer, I couldn’t help but assume Samoca cameras weren’t worth my time. As they kept showing up on my radar over, and over and over again, I finally relented and picked a nice looking model III.

After the camera arrived, I could tell the Samoca was one of those rare in between Japanese cameras, that is better than the hordes of cheap and low quality Japanese toy cameras, but still not up to the lofty standards set with cameras like the Nikon or Canon rangefinders. The Samoca is quite a bit smaller than most 35mm cameras, but has a heft that suggests a solidly built camera. At 454 grans, it is a mere 55 grams lighter than a Canon IV Sb but significantly smaller. The body covering has a nice pebbled texture which gives it decent grip. Despite being over half a century old, it is in good shape, showing no cracks or peeling, suggesting that whatever it was made of and whatever adhesive was used was well made. The chrome plating is smooth and consistently applied, showing the same type of depth and quality of a more prestigious Japanese camera like an Asahiflex or Miranda SLR. All of the engravings, from the cameras name on the front plate, to the exposure counter numbers, to the aperture scale on the shutter, are all consistently deep and painted black, showing a high level of precision.

Up top, the Samoca 35 III shows nice symmetry with identically spaced rewind and wind knobs flanking the center hump and accessory shoe. A body skin covered box in front of the top plate is where the shutter cocking plunger and shutter release are located. An exposure counter is on a numbered disc beneath the rewind knob and counts exposures up from 0 to 35. A large red arrow on the film advance knob indicates proper orientation for film advance. Cocking the shutter is done by pressing down on the plunger in front of the rewind knob. The shutter release in front of the film advance knob is threaded for a cable release.

Flip the camera over and the symmetry continues as there’s not one, but two 1/4″ tripod sockets on both sides of the camera. While I normally applaud cameras with centrally located tripod sockets, the Samoca is small enough that one on the side shouldn’t cause much of an issue, so I’m not really sure why there are two of them here, other than perhaps the camera’s designed might have had OCD. In the center is a rotating lock for the film back. With the lock pointing to the L, it is locked. Move it to the letter O and it is unlocked.

Around back, there’s little to see other than the circular eyepiece for the viewfinder and a “Made in Japan” engraving and the camera’s serial number. The sides of the Samoca are equally barren, showing a smooth metal plate with three screws on both sides. The Samoca lacks any sort of strap lug, which is unfortunate as it means your only option for using a strap is either the original ever ready case, or a tripod socket mounted one…hey, maybe that’s why they have two sockets!

Unlock the film compartment and the entire bottom and back of the camera slide off. The film compartment continues with the symmetrical theme with a polished chrome metal film pressure plate that is attached to the body of the camera and hinged at the top. The take up spool is removable, allowing for cassette to cassette transport if you wish, however the camera does not support the Leica or Contax style reloadable metal cassettes. Loading film requires you to slide in a new cassette on the supply side, fold up the pressure plate so that the film rests on the film plane, and then attach the leader to the removable spool. If you do not have the original take up spool, the plastic inner core of any regular 35mm cassette will also work, however you’ll need to tape the leader to it. Once you have the film loaded, make sure you fold the pressure plate over the film gate and film, then slide the back onto the body and lock it using the latch on the bottom and finally reset the exposure counter to 0.

Looking down upon the top of the shutter, the focus helix is closest to the body and has engraved distances from 3.5 feet to infinity. The mark for 24 feet is in red to indicate a zone focus mark for snapshots. A total motion of the focus arm is about 90 degrees allowing for quick changes to focus distance. A depth of field scale is engraved into the front plate of the camera for easy zone focus. A ring in front of the focus helix controls the diaphragm with f/stops from f/3.5 to f/22.

From the front of the camera, we see the depth of field scale above and to the left of the lens. Below and to the left of the lens is the flash sync port which supports flashbulbs only as the manual makes no mention of electronic sync.

Below and to the right of the lens is the shutter selection dial. Three speeds from 25 to 100 plus Bulb are possible with click stops at each setting. This location of the shutter speed dial is convenient for intentional shutter speed changes, but is also in a location that can sometimes interfere with your left hand while focusing the camera, causing accidental shutter speed changes.

The viewfinder is a straight through optical design. The glass in the viewfinder has a negative magnification ratio which shrinks the image seen through the viewfinder. The manual does not state what it is, but my best guess is somewhere around 0.6 to 0.7x. There are no frame lines or any kind of information about the status of the camera. The viewfinder is not very large, but is big enough that I could see all four edges of the frame while wearing prescription glasses.

I started out this section stating that the Samoca is an in between Japanese camera that’s better than the cheap toy cameras the country was known for after the war, but isn’t quite to the standards of a Konica rangefinder. The Samoca is a simple camera that is easy to use, but is not so basic that it would prevent you from making good images. This is a solid camera that after handling it for a few moments, I was excited to throw a roll of film through.

Repairs

I was lucky to get the Samoca in good working condition, but while researching the camera, I found the below site which has some instructions for repairing the camera and has some images of the camera with the top plate removed. If you have a Samoca in need of repair, perhaps the following link may be of some help to you.

https://pheugo.com/cameras/index.php?page=samoca35

My Results

I had some concerns with the functionality of the Samoca as the shutter didn’t seem to fire consistently. It would fire off 2-3 shots in a row, and then decide to skip a frame or two before working again. Not having a lot of confidence in its ability to give me a whole roll, I split a 36 exposure roll of fresh Fuji 200 with another camera and took it with me to a White Sox game in late 2022. I figured the camera was compact enough I could keep it in my pocket and if I could get some good shots, then great, but if not, it wasn’t so big as to be a hassle lugging it around a busy stadium. For the second roll, I split a roll of Kodak TMax 100 with a different camera.

The Samoca 35 III is a simple camera, but has a lot going for it. The camera is very attractive, and will definitely appeal to those of you who love symmetry (I’m looking at you Von Cabbage!), but its greatest strength is its simplicity. The location of the two levers for cocking the shutter and shutter release are easy to reach and surprisingly enjoyable to use.

The images the camera are capable of are certainly not the best you’ll get from a 1950s Japanese camera, but they’re not supposed to be. This is not a camera meant to compete with interchangeable lens German rangefinders or interchangeable lens SLRs.

Sharpness is excellent in the center with reasonable drop offs near the edges. Outdoor shots show surprisingly little vignetting. I’ve seen four element Tessars with darker corners than this simple Ezumar Anastigmat lens. Whoever designed the optics of this lens definitely deserves a pat on the back!

While shooting the camera, I did have a few instances where the shutter didn’t fire, but that’s completely understandable for a 60 plus year old camera that likely hasn’t been serviced in decades. I also found a critical flaw in the camera’s ergonomics, which is that the shutter speed dial is in a location that allows it to be accidentally changed. In a couple images, like the one of the baseball players getting ready, I had accidentally moved the shutter to Bulb when I thought I was shooting at 1/50. Although the speed dial does have click stops, they’re not very strong, so all it takes is a slight rub of the camera against something in your pocket that can spin this dial, so for this reason, it is really important that you check your speed before each and every image.

Beyond that, the lack of a rangefinder might bother some people, but the camera offers good enough depth of field that you really don’t need it so I do not consider this a con. The viewfinder is small, but hardly any worse than what other companies were making at the time. And despite the tiny eyepiece on the back of the camera, I was able to consistently see all four edges of the viewfinder window, even while wearing prescription glasses.

And that’s pretty much all there is to it. The Samoca 35 III is a simple camera with a short list of features. It only has three shutter speeds, no rangefinder, no self timer, and no automation of any kind, but that simplicity, combined with its tiny size, better than you’d expect build quality, and lens that punches above its weight, this is a formula that’s a winner in my book.

If you’re in the market for a fun and easy to use, fully mechanical, compact camera, you could do a lot worse than the Samoca. I really enjoyed this little guy and definitely look forward to shooting it again. If you come across one in decent condition for a reasonable price, definitely pick it up. I would be shocked if you ever regretted it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Samoca_35_III

https://kknews.cc/photography/5pze3q2.html

https://www.aperturepreview.com/samoca-35-ii

https://www.japancamerahunter.com/2022/04/developing-a-relationship-with-the-samoca-35-iii/

https://pheugo.com/cameras/index.php?page=samoca35

https://randomphoto.blogspot.com/2022/05/the-samoca-35-iv-diminutive-gem.html

Hello dear friend! An excellent story about Samoca! There are several Samoca cameras in my collection. It seems to me that they have a design more old than cameras of other manufacturers of the 1950s. Samoca has the spirit of antiquity…

Nice post on a camera I have never heard of or seen, but I’m hooked, will be looking out for one now. I really like the look of them and the fact very few people seem to know anything about them, thankyou for posting. Phil.