This is a Yasuhara T981, a 35mm rangefinder camera created by Yasuhara Co. Ltd. but built in Jiangxi, China by the Phenix Optical Company. The Yasuhara T981 was conceived by an ex Kyocera employee named Shin Yasuhara who created his own company with the intent of building cameras. The Yasuhara T981 was the company’s first of two cameras and uses a 39mm Leica Thread Lens Mount. A Leica copy in only the vaguest sense, the Yasuhara T981 features a Copal vertically travelling shutter with a top 1/2000 shutter speed, a TTL coupled exposure meter, hinged film door, rapid wind film advance lever and one of the largest combined image coupled rangefinder windows ever seen on a 35mm rangefinder camera. Only one lens was specifically made for the camera, a 50mm f/2.8 Yasuhara MC lens, but it supports nearly every LTM lens ever made, making for a very flexible camera.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2.8 Yasuhara MC coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Leica Thread Mount

Focus: 0.8 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder w/ Projected Frame Lines and Automatic Parallax Correction, 1.0x Magnification

Shutter: Copal Vertically Travelling Metal Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/2000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled TTL Silicon Photo Diode w/ Viewfinder Match LED Display

Battery: (2x) 1.5v SR44 Silver Oxide Battery

Flash Mount: Hot shoe and PC Port Flash Sync, 1/125 X-Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 720 grams, 525 grams (body only)

Manual (in Japanese): https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/t981.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Yasuhara T981 is a mostly faithful recreation of a classic interchangeable lens rangefinder camera but with modern touches. With support of the 39mm Leica Thread Mount, there are a huge number of excellent lenses to choose from at many focal lengths. With a modern shutter with fast 1/2000 top speed, exposure metering, and one of the largest viewfinders ever seen on a LTM camera, the Yasuhara has a lot going for it, but the camera is not perfect as it can be prone to light leaks through the SLR shutter blades, it has questionable build quality and its looks are ruined by the large and bulbous size of the viewfinder. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for an unusual mix of old and new that works quite well | ||||||

| Final Score | 8.0 | ||||||

History

The story of the Yasuhara T981 starts with Kyocera. Originally founded in 1959 as Kyoto Seramikku Kabushiki-gaisha, or Kyoto for short, Kyocera’s first products were ceramic insulators for early televisions. In the 1960s, as consumer and industrial technologies took off, Kyocera gained a positive reputation in the ceramic semiconductor industry. It’s products were used in early computers, medical equipment, and even by NASA.

In 1982, seeking more global expansion, Kyoto would change it’s name and officially become Kyocera Corporation. This began a period of rapid growth as the company acquired several other companies and produced consumer audio/visual products like CD players, radios, and laptop computers.

In October 1983, Kyocera would acquire Yashica, who in the 1970s had entered into a licensing agreement with Carl Zeiss to produce Contax SLRs, and other point and shoot cameras featuring Zeiss’s Tessar and other lenses. At first, Kyocera’s ownership of Yashica was not visible outside of the company as Contax SLRs and Yashica cameras continued to be built using the same names consumers were already familiar with. Within the next decade, Kyocera would start to release film and eventually digital cameras under their own name. The early years of the digital camera era saw many Kyocera branded cameras, many of which were sold exclusively in Japan, but some rebranded Kyocera cameras made it to western countries like the United States.

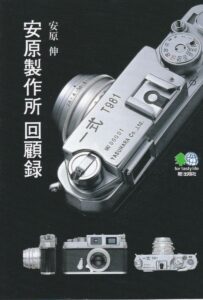

The story of the Yasuhara T981 starts with it’s founder, Shin Yasuhara who started working for Kyocera in the late 1980s. A bulk of the information about Shin Yasuhara comes from Peter Robinson’s excellent website about the Yasuhara T981 and a biography written by Shin Yasuhara regarding his time building cameras, called “Yasuhara Seisakusho Memoirs”. This book is out of print, but can still be ordered online, and is in Japanese only.

Born in 1964, Shin Yasuhara attended Kobe University near Osaka, Japan where he studied and earned his degree in Physics. After graduating, Yasuhara started working for Kyocera as an engineer in their camera division.

While working for Kyocera, Yasuhara was involved in a number of products in the Contax line including Contax SLRs and the Contax T2 compact camera. In his biography, he talks about one of the last products he worked on was a premium Contax SLR with a moving film plane. Although he doesn’t mention it by name, this has to be the Contax AX which was was the only Contax camera to have that feature.

Perhaps suffering from burn out or a loss of interest in the direction Kyocera was taking the Contax line, in February 1997, Shin Yasuhara would leave Kyocera to seek employment elsewhere. In his biography, he states that he didn’t leave Kyocera with the specific intent of making his own camera, but the delusion (his words, not mine) of creating an all new camera from scratch were there.

Using Google to translate Japanese to English can sometimes be hit or miss, so at times while reading the translated version of Yasuhara’s biography, some points were confusing to me, but it was clear to him at the very beginning that he had no idea how to build a camera, and even if he did, he wouldn’t have the resources to do so. He rented a small office which was around 25 square meters. He also knew that the cost in developing an entirely new camera from scratch could be in the hundreds of millions of yen, so if he was ever going to accomplish this feat, he needed a partner to both build the camera, but also to offset some of the development cost.

Reflecting on his experiences at Kyocera where he traveled to China to coordinate deals to manufacture cameras for Kyocera, Yasuhara says he contacted a factory which he does not name, but is almost certainly Phenix Optical Instrument Co., Ltd, in Jiangxi, China whom he had experience with and talked to them about his vision.

Reflecting on his experiences at Kyocera where he traveled to China to coordinate deals to manufacture cameras for Kyocera, Yasuhara says he contacted a factory which he does not name, but is almost certainly Phenix Optical Instrument Co., Ltd, in Jiangxi, China whom he had experience with and talked to them about his vision.

To his surprise, the Chinese factory was immediately interested in his vision, stating that his level of enthusiasm was not common for Japanese businessmen. They were used to dealing with numbers guys, and not visionary designers who were passionate about what he wanted to make. In his talks, the Chinese agreed to a deal where they would build the camera and pay for some of it’s development, but not all, in exchange for the rights to make their own camera and share in it’s profits.

For his share of the development cost, Yasuhara secured a loan from the local government who, as a result of a Japanese recession, was seeking small businesses to invest in. Yasuhara filed for the loan and was accepted as it met the criteria for business they wished to invest in.

Now fully funded, and with a partner to build his camera, Shin Yasuhara had to design the camera. His vision was for a classic interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder in the style of the original Leica, but with all modern technologies and conveniences. For the lens mount, he chose the 39mm Leica Thread Mount as it was both very simple and inexpensive to build, but also that there were millions of available lenses on the market, some of which were still being made, that could be used on his camera.

For the basic design of his camera, Yasuhara built upon his experience working for Kyocera and chose the Yashica FX-3 SLR as a starting point. Although the camera would not outwardly look like the Yashica SLR, many internal parts, such as the chassis, most of the film advance system, and the metering system were used. The shutter was a Copal design, made in Japan, which was already being used in the FX-3, so it’s choice as a modern and reliable option was retained in Yasuhara’s forthcoming camera.

Throughout his biography, Yasuhara never mentions Phenix by name, but since we know that the eventual camera was produced by them and he never mentions working with a second factory, both Peter Robinson and I have come to the same conclusion that Phenix was who he worked with the entire time.

Having sorted out the chassis and shutter for his new camera, one part that wasn’t yet finished was the viewfinder and rangefinder. Since the FX-3 was an SLR, things like the mirror box, pentaprism viewfinder, and the mechanics needed to actuate the mirror were not needed. Rather than come up with an entire new rangefinder and viewfinder from scratch, these parts came from Phenix’s parts bin.

Using the parts from the Phenix/Seagull 205, a majority of the rangefinder assembly could be adapted to the Yasuhara design. In addition to not having to design these parts from scratch, the existing design was ideally suited as it was very large and bright, and could support frame lines with automatic parallax correction, and the needed space for the match LED system which was taken from the Yashica FX-3. Unlike many contemporary rangefinders which use semi-transparent beam splitters, the rangefinder in the Yasuhara was made out of a block of optical glass, which had the benefit of being very bright, offering a high level of contrast, and also would be less likely to fall out of adjustment if the camera were to take a small hit.

The last part of the design of Yasuhara’s camera was the lens. Although the camera would use the 39mm Leica Thread Mount and therefore be compatible with a huge number of existing lenses, Phenix rebadged an existing 50mm f/2.8 design that had been built by Tiansai in China for many years. The lens would be badged with the name Yasuhara and would be the kit lens shipped with the camera. Now, with the camera’s design completed, Shin Yasuhara was ready to reveal to the world, his creation.

As part of the agreement with Phenix to build and help develop Yasuhara’s camera, they shared in some of the profits, but would also release their own version of the camera as the Phenix JG-50. The significance of the number ’50’ in Phenix’s camera was to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the birth of the People’s Republic of China, which was officially born in October 1949. Only about 500 of the Phenix JG-50s were made, making them far rarer than the Yasuhara models.

In his biography, Shin Yasuhara mentions that in early 1998, he made a website under the name Yasuhara Works and shared his ideas for a new camera that he wanted to design. Each time he came up with a new idea, he updated the site. Throughout the development process of the new camera, he would update the site. At first, few people ever saw his website because in 1998, the World Wide Web was so new, but periodically, he would receive emails of encouragement. When he was getting close to having a completed prototype, he posted that an announcement was coming on October 1st.

On the night of September 30, 1998, Yasuhara added some pictures of the completed prototype, with some information about the camera and announced that he would soon be taking pre-orders. He published his announcement at midnight on October 1st and then went to bed. The next morning, he attempted to logon to his site but couldn’t as it wasn’t responding. It took him several hours before he was able to gain access and when he finally did, he saw the number of hits on the hit counter was increasing by thousands!

Emails and requests for pre-orders came in immediately. Yasuhara was contacted by multiple members of the local media and asked to talk about his new creation. The camera hadn’t even yet been completed and Yasuhara had already gone viral!

When he officially started accepting pre-orders, a down payment of ¥5000 was required with the understanding that the finished camera might take years to complete. People accepted the risk and submitted their orders. A total of 3000 orders were received in one month. Yasuhara mentioned that one generous donor sent him ¥500,000 just to help encourage the project.

In his original announcement, Yasuhara’s new camera was given the name 一式 (Isshiki) which loosely translates to “everything you need” or “complete” to suggest that the camera had everything you needed in a modern camera that could use classic lenses. More mysteriously is the model number T981, whose meaning was less clear. Referring back once again to Peter Robinson’s excellent Yasuhara site, he hypothesizes that the letter “T” was a misspelling of the symbol 丁 for ‘ding’ and that the number 981 was actually a date code to mean 1st camera in 1998. Whether this is true or not has never been proven and is just a guess unless some other source comes along to disprove it.

An interesting side effect of how the camera was announced and promoted online is that Shin Yasuhara spent absolutely nothing on marketing or advertisement. It is not clear if that was in the original plan or not, but with the quick and immediate response he received online, there was no need to spend anything on advertising. For this reason, no ads or promotional material for the camera exist.

The first batch of cameras were completed quickly and shipments started going out in March 1999. It would take nearly two years to complete the pre-ordered cameras and after that, 1000 more were reportedly built, for a total production of around 4000 cameras. This total is disputed however as cameras with serial numbers in the 5000s exist, possibly suggesting that more than that many were built, but it is also possible that the serial numbers were not completed in sequence.

Upon it’s release, there was a tremendous amount of excitement for the camera as this was the first release of a classically styled rangefinder film camera with modern features. It’s release almost certainly helped drum up excitement for later releases of the Cosina built Voigtländer Bessa and Konica Hexar rangefinders, both in 1999.

Initial feedback about the camera was positive, but some criticism and a few problems quickly began to show up. The most prominent complaint about the Yasuhara was regarding it’s shutter. Although the Copal shutter itself performed really well, it was designed for SLRs, not a rangefinder camera. In an SLR camera, the shutter spends most of it’s time in darkness behind the reflex mirror. The mirror shields direct light from hitting the shutter blades and preventing any sort of light leaks that might make it through small gaps between the blades. In order for a focal plane shutter to be completely light tight when not in use, additional baffling needed to be included which the Yasuhara did not have.

In his excellent review of the camera on emulsive.com, Howard Maryon-Davis claims to have tested the light protection of the shutter by removing the lens with film in the camera and holding it up to bright sunlight. His test did not produce any light leaks, but that’s not to say that it still couldn’t in other situations, or using other samples of the camera. Rather than modify the shutter to add additional light baffles, Yasuhara acknowledged that users should shield the camera from bright light when changing lenses and keep the lens cap on when not in use.

Other criticisms regarding the accuracy of the rangefinder were brought up, possibly due to back focus issues. This problem was never actually confirmed by Yasuhara or in any official report, and dismissed as likely a result of the vast number of LTM lenses that have been made over the years having different tolerances which can throw off the focus calibration.

There were other criticisms about the look of the camera, specifically the huge rangefinder and viewfinder windows which made the camera look top heavy. Some contemporary reviews thought the viewfinder and rangefinder look grafted onto an otherwise good looking camera. There is some truth to this as this entire part of the camera came from the Phenix parts bin and added to the body later. Although some people liked the look of the camera, when placed side by side with other premium film rangefinders by Voigtländer and Konica, the Yasuhara does look a bit awkward.

Every one of the first 3000 T981s were sold through pre-orders directly from the company, but it is not known how the rest were sold. As best as I can tell, the camera was only sold direct from Yasuhara and was not officially exported out of Japan. For western photographers in countries like the US who wanted one, they would have had to contact a US distributor who had connections in Japan to get one.

The price of the camera was listed as ¥55,000 in 1999 and using an online international currency inflation calculator, this compares to ¥58,669.77 today, which when converting 2023 Japanese yen to 2023 US Dollars compares to just over $400 today, which if correct, means the camera was quite affordable at the time of it’s release.

Production of the Yasuhara T981 ended in 2001 and new old stock continued to be sold after that, but Shin Yasuhara was not done yet making cameras. After production finished of his first camera, Yasuhara turned once again to Phenix to help him build a second camera, which would eventually be called the 秋月 (Akizuki).

Like the T981, the new camera would have a model number of T012 and would be a 35mm rangefinder, but similarities between the two cameras would end there. Unlike the first camera, the T012 would have a fixed 30mm f/2.8 lens, and would support both aperture and programmed auto exposure. The camera would have an in-body electronic flash and would have a rectangular LCD screen on the top plate of the camera.

Unlike the T981 however, the T012 wasn’t very successful and only a couple hundred were thought to have been built. A lack of interest in a premium compact rangefinder company from a little known company, combined with the rise in popularity of digital cameras likely doomed the T012. Yasuhara would go out of business in 2004, ending all camera production, but would reappear in 2011 as a maker of third party lenses and accessories, a business they are still in today. Yasuhara’s current day website lists a variety of affordable lenses in Sony, Nikon, Canon, Fuji and Micro 4/3 mounts.

Today, the Yasuhara T981 is approaching it’s 25th anniversary, making it sort of a modern classic in that it was released at a time where it’s design was already retro, but has become collectible in it’s own right. This makes it somewhat of an odd duck for collectors. It is much newer and more advanced than the classic rangefinders it was inspired by, but is old enough that it has become a classic itself.

With at least 4000 made, finding one isn’t incredibly difficult today. Although an uncommon camera, there are many rarer cameras produced in smaller numbers which are harder to find. As I write this in July 2023, a quick eBay search returns 14 for sale with prices ranging from just under $400 to $800 making them much more affordable than other options out there.

In the time since Yasuhara made his two cameras, much has changed in the photographic world. Digital photography has put an end to nearly all mid to high end film cameras. Even digital cameras have been losing ground to smartphones, making cameras of any kind less and less common. Will we ever see a modern interpretation of a classic film camera like the Yasuhara again? Only time will tell, but for anyone who doesn’t want to wait, go buy one yourself as this might be the most affordable modern classic that will ever exist!

My Thoughts

The Yasuhara T981 is a camera I had only known of through web searches and the occasional post on Facebook camera collector pages where collectors lucky enough to have one shared theirs for everyone to see. In my quest to expand my collection, there are cameras, that I actively look for with the hope that one day I’ll find one cheap enough to able to afford, and then there’s a list of “bucket list” cameras that I’d like to at least be able to handle and if I was lucky enough, maybe shoot, but never thought I’d be able to own.

Using a tactic I’ve discussed a number of times on this site, and in my GAS Attack! Buying Cameras on eBay guide, patience and persistence would eventually pay off, and as unlikely as it sounds, patience did eventually pay off and a Yasuhara T981 came my way to be added to my permanent collection.

Reading as much as I could about the camera before it arrived, I knew this was a camera that many consider to be a very modern update to the classic Leica formula. Real Leicas are known to have exceptional build quality, and in one article that described the T981, it said, it was somewhere in between a Soviet Zorki and a real Leica. Learning more that the T981 was built off the chassis of the Yashica FX-3, I figured it would feel pretty good in my hands.

When it arrived, the camera was in excellent condition, and as promised, it’s build quality was very good, but I could see ways in which maybe it wasn’t quite “hand build German” good. The body was nicely chrome plated with black accents and thick body covering that was showing no signs of peeling or cracks. Considering this camera is quite a bit younger than the typical Leica copies I’ve handled, I expected everything to be in good condition, and it was.

If I put on hyper-critical laser focus eyes, looking for excuses to justify this was a Chinese camera not made in Germany, I did notice that the silver plating was shinier near the edges, and I could see some casting marks on the sides of the camera, especially near the eyepiece. Very, very small inconsistencies in the gap between the metal frame around the viewfinder and rangefinder windows, especially near the corners, are also evident of cost cutting, but hear me when I say this, these are all VERY MINOR! Overall, the build quality is a solid A, but not A+ if that helps you to better understand it.

Edit 10/23/2023: My comments above about the build quality were written after acquiring the camera, but before shooting it. My opinions will change on this, but more on that later.

The camera is deceivingly heavy and feels much more like a classic rangefinder than you’d expect than something based off the Yashica FX-3. The kit Yasuhara 50mm f/2.8 lens is made of brass and is very heavy. The lens weighs 196 grams by itself, or just over 27% of the camera’s total 720 gram weight. It has positive click stops and a very smooth focusing helix. The film advance lever is very light and precise, the sound of the shutter is surprisingly quiet, almost quieter I’d say than a cloth focal plane shutter on a genuine Leica, and the viewfinder is excellent. This is a very nicely built and designed camera with far more going in it’s favor than against it.

Up top, it is clear that the T981 takes it’s design from screw mount Leicas. The general location of controls and shape of the raised portion for the viewfinder and rangefinder are close enough that at a passing glance, it could be mistaken for one. But a look for more than a second and there’s quite a number of differences, not including the obvious name engraving. The rewind knob is about the same size as one from a Leica, but here has a fold out handle for easier rewinding. In the center of the top plate where an accessory shoe for a flash or auxiliary viewfinder might go, is a modern electronic hot shoe. Like the Yashica FX-103 SLR whose shutter this camera uses, the X-sync on the T981 is 1/125, up to five times faster than that of the original Leica I.

To the right is the shutter speed dial with speeds from 1 to 2000 plus B. A small post with a red dot to the left of the dial is the indicator that you must align your chosen speed to. In between B and 2000 is a small window for setting the ASA film speed. Choices from 25 to 3200 are available, and are changed by lifting up on the outer ring around the shutter speed dial and rotating it until the desired number appears in the window. Above and to the right is the cable threaded shutter release button. This forward location is more comfortable to reach than the rear location of the shutter release on screw mount Leicas and most copies. To the right is a rectangular window for the automatic resetting exposure counter, and below that the film advance lever. The film advance lever is made entirely of chromed metal but has an ergonomic shape similar to what you might expect from a 1990s film SLR.

The bottom of the camera is pretty sparse with only the rewind release button, metal 1/4″ tripod socket, and round door for the battery compartment. Not many classic Leica Thread Mount cameras were made that used batteries, the only other one I can think of is the Canon 7S. Two 1.5v SR44 Silver Oxide batteries are used to power the T981’s meter, but without them, the fully mechanical shutter will still work, just like the classic rangefinders of the past.

Note: Unlike most cameras that use SR44 (or similar) batteries in which the positive side of the battery faces the cap, on the T981, positive faces inside the camera. I made the mistake of inserting batteries in the way I would most other cameras and thought that the meter wasn’t working. It doesn’t help that there is no sticker or engraving anywhere on the cover or inside of the battery compartment letting you know correct polarity.

Around back, the most notable thing is the huge rectangular opening for the viewfinder. Like the windows up front, the massive size of the opening is a bit jarring at first, as even the largest Canon and Soviet screw mount viewfinders were quite a bit smaller than here. The large size is welcome for wearers of eyeglasses, and makes composition super easy, but is a bit weird looking. To the right is a PC flash sync connector, which on this example still has the plastic plug installed, covering the contacts. A large flat head screw in between two smaller screws likely is a cover for a rangefinder adjustment. I did not take it off to find out for sure though, although I cannot imagine it is used for anything else.

The sides of the camera are fairly symmetrical with little to see other than a front angled strap lug. The presence of strap lugs on this camera is a nice addition considering many screw mount Leicas and their copies did not have lugs. That they are facing forward helps prevent the camera from tilting forward while hanging from your neck.

The Yasuhara T981 has a hinged rear film compartment, which is an improvement from the bottom loading design of early Leicas. Many other screw mount copies like those made by Canon, Nicca, Tanack, and various Soviet factories switched to hinged rear backs as well, so it’s inclusion here should not be a surprise to anyone. What is unusual is in that the film back opens like a modern camera in which an upward tug of the rewind knob releases the latch. Lift up on the knob and the right hinged door swings open to reveal the film compartment.

The film compartment looks straight out of 1979, because the camera it was built on the chassis from is from 1979, so that means no DX encoding pins in the take up side, no electrical connections for a date back, and no automatic film load mechanisms. Film transports from left to right onto a non removable, plastic, and multi-slotted take up spool. Film winds on the spool clockwise, which means it rolls opposite that of the direction it is in the cassette, which is said to help with film flatness as it transports through the camera. Inside of the film gate are the metal blades from the vertically traveling shutter. The inside of the door has a large and black painted metal pressure plate covered in divots which help reduce friction as film passes across the plane. As with other cameras from it’s era, the T981 uses foam light seals on the door hinge and inside the door channels. Unlike many collector cameras however, the T981 is still new enough that the ones found here are almost certainly still going to be in good condition, not having crumbled away like on older cameras. That still doesn’t eliminate the need to inspect them every now and then however.

When Shin Yasuhara sought out to design his own camera, one of his goals was that it would be compatible with the huge amount of classic Leica Thread Mount lenses out there. In order to do that, the T981 is equipped with a standard 39mm screw mount which accepts almost every lens that works on a Leica. For those who wanted a more modern lens, Phenix, the Chinese company who built the camera created a Yasuhara branded 50mm f/2.8 multi-coated lens for the camera. The Yasuhara lens won’t excite too many people with it’s specs, but it’s compact size, good build quality, and modern 4 element optics meant it would be a good performer. Like all screw mount cameras, removing and installing the lens is a matter of “lefty loosey, righty righty”. Inside of the lens mount is a round rangefinder coupling, just like those found on original Leicas and quality Japanese copies. To the left of the lens mount is a mechanical self-timer lever which activates an approximate 8 second delay when firing the shutter.

Looking down upon the top of the Yasuhara branded lens, an expected layout consisting of the aperture control with f/stops from 2.8 to 22 is closest to the front. The focus ring is next, with indicated marks from 1 meter to infinity, and finally an engraved depth of field scale nearest the mount. This being a Japanese only camera, the focus ring is indicated in meters only, and requires about a 100 degree turn from minimum to infinity. A large metal tab with a finger size indentation is located near the bottom of the lens and is conveniently located for finger tip focusing.

Without a doubt, the most striking feature of the T981 is it’s monster viewfinder. It is hard to miss the two large rectangular windows perched atop what is otherwise a somewhat compact and cleanly styled camera. If there ever was a design element on a camera that was function over form, this is it. The strange thing is, the viewfinder itself isn’t any larger than other large viewfinder cameras like the Voigtländer Vitomatic IIa or the Chinese Seagull 205 rangefinder that this is based off. What makes the window seem so large here is the relatively compact size of the T981’s body and it’s close similarity to that of a screw mount Leica which always had a much smaller viewfinder.

Looking through the viewfinder, the image is gloriously large and crystal clear. Seriously, this is the clearest viewfinder on a rangefinder camera I’ve ever seen. Projected frame lines representing a 50mm image are very easy to see with good contrast. The frame lines support automatic parallax correction which means that as you focus the lens closer up, the frame lines shift down and to the right to accommodate parallax error. The rectangular rangefinder patch is very big and has good contrast allowing you to see the double image in even the most challenging lighting conditions.

With batteries in the camera, the T981 has a match LED display near the left side of the viewfinder. A red + and – sign indicate over and under exposure, and a green dot indicates correct exposure for the lighting conditions and exposure settings the camera is pointed at. I often struggled with seeing the LEDs as they easily get washed out in brightly lit outdoor scenes and also that in order to see the LEDs, my eye had to be in a very specific position as they would sometimes disappear. This isn’t a deal breaker, but definitely reduced the usability of the metering system.

Overall, the Yashuara T981 is an impressive camera. A modern take on the classic Leica Thread Mount rangefinder formula. Its mixture of old meets new is unlike most other cameras out there, and while my first impression did detect a couple minor nitpicks, I felt that overall, this should be a very enjoyable camera to shoot. Of course, just because something should be true, doesn’t always mean it will be…

My Results

Having never shot a Yasuhara before, but thinking that since it is one of the younger film cameras I’ve ever reviewed, I felt pretty confident in its operational ability, so I decided to take another risk on the film I shot in it. Along in the batch of cameras that the Yasuhara came in, I also had a couple rolls of Fuji Industrial 100 Color film. I am not totally sure that “Fuji Industrial” is the correct name for the film as all the writing on the green and white box it comes in, is entirely in Japanese and that is the name that it is often referred to online, but that’s what I’m calling it. From what I gather, this film is a 100 speed color film similar to Kodak ProImage 100 in that it should have somewhat muted colors, fine grain, but excellent sharpness.

While I do have at my disposal a huge number of excellent LTM lenses I could have used on the camera, that it came with the 50mm f/2.8 Yasuhara lens made specifically for this camera, I figured that would be the ideal lens to use. Featuring run of the mill specs found on many other lenses of its type, the Yasuhara should be good enough to produce nice looking photos.

As I had hoped, the images from the Chinese lens were excellent and very typical of the best 4 and 5 element f/2.8 lenses made throughout the 20th century. Although I don’t have any scientific proof of this, I would suspect that the modern lens coating used on this lens should render better contrast and color reproduction than a similar mid century lens with the same specs.

Sharpness was excellent from corner to corner with minimal softness near the edges and almost no vignetting. Colors were excellent as was contrast even on the expired Fuji Industrial 100. Strangely, the film’s reputation of making slightly muted colors didn’t match my results as I found most images were very vibrant, at least on par with Fuji’s 200 and 400 North American emulsions. These images were as good as any basic rangefinder or SLR made in the mid or late 20th century. While I likely could have used a lens with more “pop” that delivered corner to corner sharpness, I was quite pleased with the kit lens here, and had I been an original owner of this camera and lens, seeing these images would have lessened the desire to get a more higher spec lens.

Using the camera was a joy as I found the ergonomics to be as good as any I’ve handled on a screw mount rangefinder. The shape and size of the body and location of critical controls like the shutter release and film advance lever were instinctual to me. I also appreciated the Leica style focus “pad” on the lens which allowed me to easy focus the lens with a flick of a finger. I would have never guessed the T981 was based off a SLR as the body seems smaller somehow. Clearly, I need to get a Yashica FX-3 to accompany this as I really liked the feel of the camera.

So far so good, right? Unfortunately, for all of the good things I can say about the lens and ergonomics, the T981 has a number of “buts”.

One part of the camera that I’m having the most amount of trouble coming to a conclusion on is the massive viewfinder. To anyone who has read more than one review on this site, you know that I heavily value a good viewfinder. I have terrible vision and anything a viewfinder can do to make it easier for me to compose and focus my image, the better. The one on the T981 is huge, the frame lines are easy to see and the large rangefinder patch has excellent contrast making focusing a sharp image in low light a snap.

For such a large viewfinder, I found the location of the frame lines to be at the very limit of what I can see while wearing glasses and even then, I have to press my face uncomfortably close to the back of the camera to see them all at once. It works, but isn’t as gloriously easy as you might think based on how big it is. In addition, while it is very cool to have an exposure meter on what is otherwise a classic LTM camera, the location of the LEDs are within the frame lines and get washed out easily outdoors. I found that while shooting the camera in bright sunlight, I really struggled to see the LEDs at all. Indoors, the red LEDs for + and – are reasonably bright, but the green circle in the middle is still pretty dim. This being the only T981 I’ve ever used, I can’t say if this is normal or unique to my example, but either way, I feel as though this aspect of the metering system could have been better.

Earlier in the history section of this article, I speak of an issue often reported when the T981 first debuted in which the shutter used in this camera was originally designed for an SLR and can cause light leaks if direct sunlight hits the back of the shutter blades as they don’t offer enough light sealing protection. I’ve read that in certain instances, you’ll see light leaks on your images if the light hits the shutter a certain way, but I am happy to report that this wasn’t an issue for me. I took no special precaution while shooting the camera outdoors to shield the lens from sunlight. At one point, I even took the lens off the camera outside and let light hit the blades directly and there were still no leaks. That’s not to say that owners of this camera still shouldn’t take precautions, it’s not the major deal breaker the original reports made it seem like.

Edit 10/23/2023: I started on this review before I shot the camera, and in the section above, I talk about the build quality being pretty good. Not as good as an original Leica, but not bad either. Sadly, while shooting the camera, the shutter release completely broke off. Having shot nearly 400 different cameras for this site, I am no stranger to cameras failing mid roll, but I have never had a shutter release just break off. I can’t even claim responsibility for me dropping the camera or it taking a hit somehow as it happened while I had the camera in my hands in between shots.

Inspecting what is under the shutter release, I can see it is held on by a very small piece of plastic that simply cracked, probably due to the plastic getting brittle over time. Of course, this could be specific to my example, but after getting a better look at how this part of the camera is constructed, I can conclude that negative stereotypes of Chinese build quality are rearing their ugly head here. It is clear that from the outside the Yasuhara T981 looks respectably tough, on the inside, the camera is a cheap Chinese rangefinder.

The Yasuhara T981 is a very cool camera with a lot to like but there is also quite a bit not to like. Build quality is suspect, the viewfinder, despite being large is difficult to use with prescription glasses, the metering system easily gets washed out in bright lights, and I just could not get over the gaudy design of the viewfinder. Where German companies usually valued function and form together, it is clear that with the Yasuhara T981, form took a back seat.

To be fair, the T981 has enough features to meet Shin Yasuhara’s prerequisite of a classic camera with modern conveniences and I think the decision to build the camera in China made sense as it allowed the camera to be sold at a price people could afford, rather than some hand built model build in a specialty Japanese factory whose end price would have been quite high. Using parts from a reputable camera like the Yashica FX-3 was also a good decision as the shutter works well, the film advance, shutter speed dial, and most of the cameras controls are excellent. The 4 element Yasuhara lens won’t wow you with its specs, but it more than delivers the good in image quality.

In the world of modern interpretations of classic rangefinders, you have Nippon Kogaku’s 2000 and 2005 re-releases of the S3 and SP, Cosina’s Voigtländer and Rollei branded LTM, Leica M, and Contax mount rangefinders, and the Yasuhara T981. In every one of those examples, the people who created them successfully mixed old with new, with only a small amount of compromises.

Despite a few pretty significant issues, I still think the Yasuhara T981 is a worthy addition to your collection as it a lot of fun to shoot and is capable of great images, but I doubt it would ever replace any of the huge number of classic German and Japanese rangefinders. At least, I know it won’t for me.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Yasuhara_T981

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%AE%89%E5%8E%9F%E8%A3%BD%E4%BD%9C%E6%89%80 (in Japanese)

https://www.cameraquest.com/yasuhp.htm

https://www.cameraquest.com/yasu2.htm

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/kVmqGOY6fM8HSIg7Kq1h6Q (in Chinese)

https://web.archive.org/web/20061102004119/http://homepage3.nifty.com/madam/camera/YASUHARA.html

I spot a (most likely) translation error in the following sentence.

“ Phenix rebadged an existing 50mm f/2.8 design that had been built by Tiansai in China for many years”

“Tiansai” is actually the local translation or Tessar. So “Tiansai” is probably referring to the 50/2.8 lens design and not a specific company.

I was intrigued by this camera and bought one direct from Japan, in 2019. The large viewfinder sealed the deal as all other LTM rangefinder cameras (save for the ubiquitous Canon 7) were too small for my imperfect vision. Reading your review brought up the same issues I suffered; virtually impossible to use the meter in daylight and build quality. Specifically in my case, this was the first 35mm camera I had ever used that could not wind on film to the final frame. In this case, film wind ended at frame 19! It was an expensive purchase but I sold it and recovered the original investment made., Yes it’s rare and a more compact, metal alternative to the plastic Voigtlander Bessa R, but it was an expensive failure for me. The one positive I take from this unfortunate experience though, is I always run an exposed roll of film through every camera I buy, as soon as I receive it. I’m happy to say, every purchase made since, has passed the “film test” with flying colours.