This is a Zeiss-Ikon Hologon Ultrawide a 35mm camera made by Zeiss-Ikon AG in Stuttgart, West Germany starting in 1970. The Hologon Ultrawide is unusual as the camera itself is nothing more than a vessel to use the Carl Zeiss Hologon 15mm f/8 lens on a body other than the Contarex, which up until that point, was the only camera it could be used on. The Hologon is a very compact ultrawide triplet lens whose design requires it to be mounted extremely close to the film plane, something that traditional SLRs struggle with. By creating the Hologon Ultrawide camera, the body from a Contarex is modified to remove the prism, reflex mirror, and permanently mount the lens inside of the camera. In a sense, the body only services as a light tight box to hold the film.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 15mm f/8 Carl Zeiss Hologon 3-elements in 3-groups

Focus: Fixed, Depth of Field is about 1.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed Optical Wide Angle Viewfinder w/ Bubble Level

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 1112 grams (with handle and shutter release, 752 grams (camera body and lens only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Zeiss-Ikon Hologon Ultrawide is a camera built entirely around a lens. With fixed focus and a fixed f/8 aperture, the camera’s only controls are the shutter speed selector, film advance, and large wide angle viewfinder. Using the camera is extremely easy, but composing images through it require your brain to “see” the world differently, which can take some getting used to. Once you do though, this is a special camera that can capture images unlike any other. It is a specific use tool, but when you need it, is a lot of fun! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for undeniable cool factor, there has never been another camera like it | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

History

In the realm of influential leaders in lens design, it is hard to argue against Carl Zeiss being the most successful lens makers of all time. While a good number of lenses were produced by non-Zeiss companies, with a catalog of lens designs to their credit such as the Tessar, Planar, Sonnar, Biogon, Distagon and many, many others, there is a good chance that almost everyone who has ever picked up a camera at least once in their lifetime has either used a lens directly made by Zeiss, or is copied from a Zeiss design.

In the realm of influential leaders in lens design, it is hard to argue against Carl Zeiss being the most successful lens makers of all time. While a good number of lenses were produced by non-Zeiss companies, with a catalog of lens designs to their credit such as the Tessar, Planar, Sonnar, Biogon, Distagon and many, many others, there is a good chance that almost everyone who has ever picked up a camera at least once in their lifetime has either used a lens directly made by Zeiss, or is copied from a Zeiss design.

By the middle of the 20th century, lenses with focal lengths from around 28mm to about 300mm were common and easy to build by a number of German and Japanese lens makers. Schneider-Kreuznach, Meyer-Optik, Nippon Kogaku, and Asahi Optical all made world class lenses that could compete with the best of the best.

When it came to lenses outside of that “common” zone, things got more difficult. Lenses longer than 300mm were often extremely large and heavy, and required large pieces of precisely ground glass, and in the case of catadioptric (or mirror) lenses, also required precision curved mirrors.

On the wide angle side, lenses wider than 28mm were often referred to as ultra-wide angle lenses. Most lenses are what’s called rectilinear, in which the lens is able to maintain straight lines throughout the exposed image. Some lenses with extremely short focal lengths are not rectilinear. These lenses are more commonly referred to as “fisheye” lenses, in which lines are curved. The image produced by these lens has the effect of looking through a glass bowl. They have the advantage of capturing a huge amount of visual information, but at the expense of no straight lines, hence the fisheye nickname.

After World War II, the US Signal Corps, having been aware of advanced lenses and optical equipment being designed by Carl Zeiss in Jena, it was suspected that a treasure trove of experimental lenses and other optical equipment may be there for US troops to confiscate. Under the leadership of Lt. Colonel Harry B. Cuthbertson, a collection of more than 2000 lenses was discovered and shipped to the Signal Corps Photographic Center at Astoria, Long Island and then again to Fort Monmouth in New Jersey where the collection could be cataloged and analyzed.

Many strange and exotic prototype lenses were cataloged and researched by the Signal Corps, one of which was an ultra wide angle 1.9cm f/6.8 fish-eye lens code named V1936 Nr. 18 (the V stands for “Versuch” or “Experimental”). The lens had the official name Sphaerogon, which was used on a variety of extreme wide angle lenses created by Zeiss during and after the war, but V1936 Nr. 18 was the widest and the fastest. The Sphaerogon was so unique, that it was permanently mounted to a dial set Compur leaf shutter and installed into a Voigtländer Bessa 6×6 camera. The lens was tested and revealed to the public in the September 1949 issue of Modern Photography in an article called “Bug Eye Zeiss”.

Although the 1.9cn f/6.8 Sphaerogon lens was only a prototype and never went into production, some less advanced versions did, as did fish-eye lenses by other manufacturers such as the 8mm f/8 Nikkor from 1962 and f/7.5 Nikkor from 1966.

In the years after the war, Carl Zeiss would continue to research and develop new lenses. At first, the widest lenses were fisheyes, but soon, rectilinear ultra wide angle lenses started to appear. By the mid 1960s, options included Zeiss’s own 18mm f/4 Distagon made for the Contarex, Asahi’s 18mm f/11 Takumar, and Canon’s 19mm f/3.5 lens.

In a never ending one-upmanship of lens design which still continues to this very day, optical engineers at Zeiss wanted to push beyond the 18mm barrier with an even more ultra-wide angle lens. There, one of Zeiss’s lead designers, Dr. Erhard Friedrich Glatzel got to work on a new lens. Glatzel had been with Zeiss since 1954 and by the mid 1960s was already in charge of the lens design department. His previous work included designs for the Biogon, Distagon, and updated versions of the Tessar, Sonnar, and Planar. One of his most famous achievements was the 50mm Planar f/0.7, the world’s fastest lens, designed specifically for NASA’s Apollo missions, and later used by director Stanley Kubrick while filming Barry Lyndon.

In September 1966 at that year’s Photokina, Glatzel would reveal the Hologon, an ultra wide angle 15mm f/8 triplet that had an unusual design. The root of the word Hologon is taken from the latin word “holos” which means “everything”.

The Hologon was innovative for a number of reasons, one of which was that it was one of the first Zeiss lenses designed with the use of computers. Dr. Glatzel was a big proponent of the possibilities of computers, saying that the design time for a new lens could be dramatically reduced with their use. The computer used was an IBM 7090 which Zeiss had purchased for this specific purpose at a cost of roughly $2.9 million, which when adjuster for inflation, compares to around $28 million today!

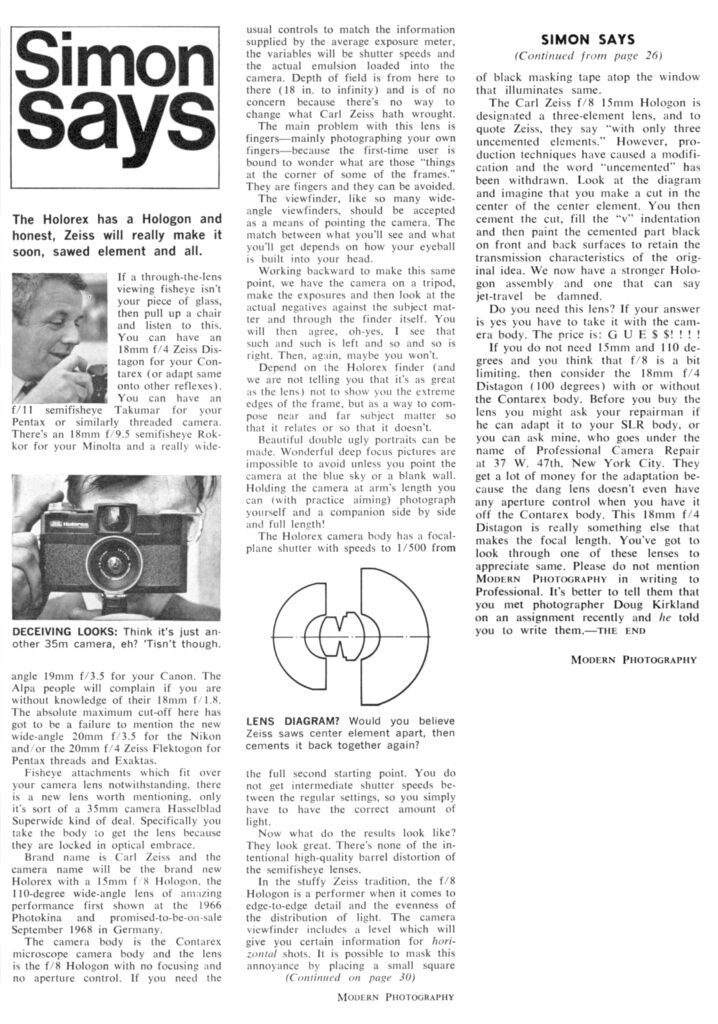

The new lens had only three elements, the front and rear of which were shaped almost like a sphere. The elements themselves were tiny and tightly packed together, so tight in fact, that there was not enough room between them to insert a diaphragm. As a result the Hologon had a fixed f/8 aperture that could not be changed. In addition, the light path created by the Hologon required the rear element of the lens to be a mere 4.5mm away from the focal plane which meant that not only would the lens only work with focal plane shutters, but also that it could not be used in a traditional reflex camera.

Since the lens could not be used in an SLR, and had far too wide of an angle to be practical in a rangefinder, it was adapted to a specially modified microscope Contarex body. The mirror, mirror box, and entire viewfinder was eliminated, leaving only the body, shutter, and film compartment from the Contarex. The Hologon lens was permanently mounted inside the camera with the front lens element almost flush with the front of the camera and the rear element only a millimeter away from the cloth shutter curtains.

Since through the lens composition was not possible, a custom built, and egregiously large viewfinder was added to the accessory shoe, to approximate the 15mm 110 degree field of view. The viewfinder itself was almost as large as the camera, and although I could not find any reference to it, must have weighed a ton.

In a short article from February 1967, the preview of the Holgoon from the previous year’s Photokina suggests the lens and camera would be available later that year with prices starting around $300.

It was not until two years later at the 1968 Photokina that a more practical, consumer friendly version of the Hologon would make its debut. Like the 1966 prototype, the new Hologon was permanently installed into a modified microscope Contarex, but instead of the huge clip on viewfinder, a much smaller one was built into the top plate of the camera, still offering an approximate 110 degree field of view. In addition, a bubble level was added to aide the photographer in keeping the horizon, or horizontal lines level.

Interestingly, the viewfinder required 7 elements to accomplish its job, compared to the actual lens which only had 3. Another change to the 1968 version was that the camera was to be called the Holorex (clearly an amalgam of Hologon and Contarex).

In another preview of the Hologon lens and Holorex camera from the July 1968 issue of Modern Photography, comments about the lens performance were positive. High marks were given to the amount of visual information captured with a 15mm lens and that the Hologon’s depth of field of 18 inches to infinity offered a great deal of flexibility. Vignetting and distortion near the edges was noted, but was completely understandable considering the pioneering design of the ultra-wide angle lens. In this article, no price was given, other than that they could only GUE$$ at what would likely be a high price.

Actual production of the Holorex camera would be delayed another year to late 1969 at which time the Holorex name was dropped and the camera was officially renamed the Zeiss-Ikon Hologon Ultrawide. According to Larry Gubas’s “Zeiss and Photography” book, only a single batch of 1400 cameras were made in 1969 with the camera officially going on sale in the spring of 1970.

When the Hologon Ultrawide went on sale, it came with a removable hand grip with remote trigger release. Although the camera could be used without the grip, without the grip, it was extremely easy to capture your fingers in the exposed image due to the ultra wide angle of view offered by the Hologon. One additional accessory was not included with the camera, could be optionally purchased which was a center weighted neutral density filter that helped even out the exposure across the image, helping to reduce vignetting that was visible in nearly every shot.

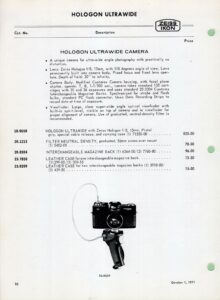

Prices for the Hologon Ultrawide were quite a bit higher than the $300 estimate from the February 1967 preview. According to Larry Gubas, catalog prices varied from $750 in November 1969 to $825 in February 1971. The center weighted filter was an additional $70 to $78 depending on when it was advertised. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to an astounding $6100, $6325, $570, and $600 today!

If the prospect of a unique and highly specific camera with limited flexibility wasn’t enough to drive most customers away, its price definitely did. The Hologon Ultrawide sold very slowly, and no additional cameras were produced after the original batch of 1400 from late 1969. Additional challenges within Zeiss-Ikon also didn’t help as the company was struggling across the board with all products. By 1972 all camera operations would be discontinued and the era of Zeiss-Ikon in West Germany came to a close.

Carl Zeiss, who operated as a separate controlling entity of Zeiss-Ikon would continue to produce lenses, and around the time of the end of camera production, would fulfill an order of 400 Hologon lenses ordered by Leitz, adapted to the Leica M mount. Only one production run of 400 Hologon M-mount lenses were produced and sold out within a month. These lenses are extremely rare and highly sought after by collectors.

In the years after the Hologon’s era, lens designs continued to advance. Eventually other manufacturers like Nippon Kogaku, Canon, and others would produce rectilinear 15mm lenses that were faster, had traditional diaphragms, and did not require such specific lens mounts. Lenses like the Voigtländer Super Wide Heliar 15mm f/4.5 and Nikkor 10-20mm f/4.5-5.6 can be bought today at prices that are a small fraction of the original Hologon, have superior optical performance, and can be used on a number of “regular” cameras, but that doesn’t make the Hologon’s achievement any less significant.

The Hologon was a tremendous accomplishment and rightfully wowed people for generations. Despite there being cheaper, faster, and better performing lenses today, shooting a camera with one of these classic super wide angle lenses is a sight to behold, whether you’re using the Leica M-mount version of the one permanently embedded into the Hologon Ultrawide camera.

Today, the Hologon Ultrawide is extremely collectible. That only 1400 were ever made means they are very difficult to find today. The good news is that these were proprietary cameras that likely saw very little use, so examples today can usually be found in excellent to near mint condition. The cloth shutter from the Contarex has proven to be as reliable as cloth shutters from other 1970s SLRs, and usually holds up today. If you are fortunate enough to find a Hologon Ultrawide, be sure to get the complete kit as both the handle and center weighted filter are both very useful. Even if you can’t find them, picking one of these up for anywhere close to an affordable price is not likely to happen often, so if you get a chance, definitely take it.

My Thoughts

Who doesn’t love wide angle lenses? Being able to fit more into an image than you would otherwise see looking through a standard prime is inherently cool and one of my favorite parts of photography. Of course, there are many very cool things you can do with telephoto lenses, but I’ve always found longer lenses to be more of a specific use type of thing, whereas a good 28-35mm wide angle lens can be used for photographing things from a child’s birthday party, to a classic automobile show, to closeups of flowers.

When it comes to ultra-wide angle lenses wider than 20mm however, I have far less experience, especially with film cameras. Sure, 16-18mm crop sensor zoom lenses are extremely common and border into the realm of ultra-wide angle, but in terms of dedicated lenses with a single focal length, my experience is only with the Voigtländer Super Wide Heliar 15mm from the Bessa L and some Tamron 17mm lens from many years ago which I barely remember.

This Zeiss-Ikon Hologon Ultrawide comes to me from Kurt Ingham, my friend and collector who recently passed away. The Hologon was one of the last cameras Kurt sent me before he passed. He had hoped to see this review when it was completed, but life had other plans.

Thankfully, Kurt didn’t just send the body, but also the original handle grip with remote shutter release, center weighted filter, and the leatherette case that the kit would have original came in. Everything was well presented and up to typical Zeiss-Ikon standards. I had previous experience with the Zeiss-Ikon Contarex Bullseye so I had at least a little idea of what to expect when it arrived.

Picking up the Hologon Ultrawide, the camera felt both solid and heavy, while also being lightweight at the same time. What I mean by that is, the body is just like the body of the Contarex. From behind the cameras look almost identical with the only noticeable difference between this and my Contarex Bullseye was the color, the inclusion of plastic tip on the end of the film advance lever, and the lack of a prism. It was interesting to notice how much of a difference the lack of a prism, mirror, and mirror box make as the Hologon Ultrawide feels significantly lighter. The weight of the Contarex body is 924 grams and the Hologon Ultrawide body and lens is 752. If there was a way to separate the lens from the body, the difference in weight between the two would be even more noticeable.

Another striking difference is how tiny the lens is. From the side, no part of the lens is visible from the front of the camera. The entire three lens elements are contained within the space of where the reflex mirror is on the Contarex. If there was any doubt that this lens wouldn’t work in a traditional SLR, this is it. In fact, even with the Hologon Ultrawide specific front lens cap, the camera looks no different than a regular SLR body with a body cap on.

Up top, the Hologon Ultrawide definitely looks strange as the lens cannot be seen from this angle, nor is there a standard prism or waist level finder like you’d expect to see on any other camera. On the left is a rewind knob with fold out handle and film reminder dial beneath. The Hologon Ultrawide has no meter, so this dial is just there for your convenience. In the middle above the viewfinder is the opening for the bubble level which can be read both through the top plate and from within the viewfinder.

To the right is the film advance knob with integrated exposure counter and shutter speed dial beneath. The shutter speed dial works similarly to the one on the Contarex, except it replaces the top 1/1000 shutter speed with a T setting for timed exposures. I am uncertain of why this switch was made, as I would think one extra faster shutter speed would be more useful than a dedicated Timed exposure setting. The exposure counter is subtractive, showing the number of shots remaining on a roll of film and must be manually reset after loading in a new roll.

Each of the sides and the back of the camera are pretty barren with little to see. Each side has a chrome metal strap lug, which is nice for those long treks in which having a camera at the ready without occupying your hands is a nice convenience. The circular eyepiece on the back is internally threaded, suggesting that all eyepiece accessories made for the Contarex should fit the Hologon Ultrawide.

The base of the two cameras are very similar, with the same dial keys on both sides of the camera for unlocking the film door, plus a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket.

Like the Contarex, the door lock on the right doubles as a rewind release. With this lock turned towards the “R” the film transport is deactivated for rewinding the film at the end of the roll. Minor differences between the Contarex are in the shape of the foot around the tripod socket, and that the Hologon Ultrawide is engraved “Made in West Germany”, compared to just “Germany” on the Rex.

Like the Contarex the Hologon Ultrawide is based off, the back of the camera slides completely off the camera revealing the film compartment. Unlike my two other Contarexes, there are additional baffles that wrap around both sides where the cassette and take up spool go. Whether this was a design decision made for later cameras, or if it was somehow necessary for the Hologon Ultrawide, I cannot be certain. Another difference is a red plastic clip on the base of the take up spool, which holds the leader in place when loading in a new roll of film.

The edges of the film compartment are very deep and have no light seal material of any kind. This means that no rotted foam seals need to be scraped off and replaced like other cameras of its era. The film pressure plate is a large piece of flat black metal. No additional features to smoothen film transport are present.

The viewfinder is…something else. In my research for this camera, I learned that the optics required to approximate a 15mm focal length and 110 degree field of view consist of 7 elements. It would seem that just as much effort, if not more, went into the viewfinder than the lens itself, yet the image seen through the viewfinder isn’t very good. Lines have extreme curvature distortion and color fringing. Near the edges of the viewfinder, the optics are so bad, it is difficult to make out fine details. I would compare the look through the viewfinder to be similar to that of cheap plastic cameras. But this is no cheap plastic camera. I seriously expected a bit nicer of a viewfinder on this camera.

On the plus side, it is big, bright, and assuming I can approximate what will be captured on film, I guess it works good enough. Below the visible viewfinder is a reflected image of the yellow tinted bubble level on top of the camera. This bubble level is only useful for vertical alignment and not horizontal as the bubble goes forward and back, with correct alignment when it is between two black lines. Other than the bubble level, there is nothing else to see within the viewfinder, nor is there any ability to “see” focus. Not that you need it though as the fixed f/8 aperture delivers depth of field from 18 inches to infinity.

Up front, the Hologon Ultrawide has all of the controls of a fixed focus point and shoot camera….because it basically is a fixed focus point and shoot camera. Other than the curvature of the front element and vanity ring, the only other thing to see are the threads for the proprietary lens cap and filter made specifically for this camera. Because of their location around the outer perimeter, you cannot use normal filters or lens caps on this camera.

The Hologon Ultrawide has no focus ring, no aperture ring, no depth of field preview, nothing, not even a self-timer, which actually would have been useful. With the huge amount of information that the 15mm lens is able to capture, the Hologon Ultrawide would have been a good camera for group photos in which the photographer may have wanted to include themselves in the image.

When purchasing the Hologon Ultrawide, it would have come with a large black pistol grip and remote shutter release cable like in the image to the right. Unlike other cameras with optional pistol grips, the one here isn’t really optional as it is very difficult to hold the camera without getting your fingers in the image. With other wide angle cameras like the Widelux or Bessa L with 15mm Super Wide Heliar lens mounted, the 15mm Hologon lens is recessed so far inside of the body that there is no room for your fingers to hold the camera without getting them in your image. With the handle mounted, you can be sure there won’t be any unwanted body parts in your images. Not shown in this image, but the handle can be mounted to the camera in one of eight positions, so that it can be angled to the left, right, or even backwards if you so wish.

The Zeiss-Ikon Hologon Ultrawide might be the simplest, most impractical camera ever built. A proprietary camera built exclusively for one lens. Its exclusivity extends beyond the lens to a very small group of people able and willing to afford it. The camera can best be described as a “one trick pony”, a very EXPENSIVE one trick pony, but boy is that trick neat! For regular readers of this site, you should know that this is the time where we get to see some sample images, so let’s get to it!

My Results

Immediately after the Hologon Ultrawide arrived from Kurt, I struggled to contain myself so I quickly loaded in a fresh roll of Fuji 200 and took it out on a spring walk through one of my favorite local photographic hotspots, downtown Crown Point where I took some of the same photos I’ve taken with many other cameras, except this time seeing them with the perspective of a 15mm lens.

With bated breath I developed and pulled my first roll of film from the Paterson tank. While there was no doubt in my mind that a Zeiss-Ikon product would create great images, shooting such a special use camera with a fixed focus, fixed aperture lens, I had no idea of what kinds of images I would get. Furthermore, as the Hologon viewfinder was not at all coupled to the taking lens, looking through it only approximates what you’ll capture on film.

As it turned out, nearly the entire roll turned out mostly great. The camera unfortunately has started to develop some pinhole light leaks that show up in some images, however this is an age related concern and not anything that is the fault of the camera. Unlike other recent cameras I’ve shot with wide angles of view, using the pistol grip handle meant that my entire roll was free from seeing my own fingers in the images! I did tend to overexpose a few shots here and there, but mostly, I nailed exposure.

Although I did have the center weighted neutral density filter made for the Hologon Ultrawide, after seeing the first roll of images without it, I chose not to use it as I actually enjoyed the look of the vignetting. In my opinion, the “imperfect” corners helps to accentuate the ultra-wide angle look of the images. When making close up portraits with the camera, I felt the darkened corners helped to accentuate what was in the middle. In hindsight, I probably should have given it a try, so maybe I’ll do that on some future roll. But at the very least, if you find yourself an owner of one of these cameras and are missing the filter, I don’t think you need to go out of your way to find one.

With or without a filter, the images from the 3-element Carl Zeiss Hologon were glorious. I’ve shot ultra wide angle lenses before such as the 10-20mm Nikkor DX Zoom, there seems to be something distinctly unique about the images this lens makes. Maybe its that I’m not used to such a wide field of view on film or maybe it is just some kind of optical voodoo, but I thought the images looked great. That anything 15 inches to infinity is in focus also allows for some creative forced perspective that looks really cool. I lack the optical vocabulary to accurately describe what’s happening when shooting a lens this wide, but if I had to summarize it into one word, it would be, “Wow”.

We are lucky today to have access to such a wide range of lens options, so it is important to remember that back in 1970 when this camera made its debut, shooting anything at 15mm was a luxury. This camera was not cheap when it first came out so those who could afford it were treated to images that couldn’t be had any other way. I still believe that even now, more than half a century after the Hologon Ultrawide made its debut, the images it makes are still impressive.

Although the camera is technically easy to use with its minimal controls, the greatest challenge to getting good image from it, is having to “reprogram” your brain to see like a 15mm lens does. The human eye does not see the world like the Hologon, forced perspective, distortion, and vignetting will be present in your images, and while great images can be made, getting those great images does take some practice as not every scene benefits from a 15mm perspective.

An interesting side effect of the Hologon lens, is that due to the close location of the rear element to the film plane, when an image is exposed onto the film, light from the lens extends underneath the edges of the film gate. This results in images that are slightly larger than 24mm x 36mm. Looking at the developed negative, each exposure touches each other, which on any other camera, might suggest a film transport problem, but on the Hologon Ultrawide, you’re just seeing a little extra image in the blank space that would normally be in between each image. When cutting the film after processing, you will need to take extra care to cut as close as you can between the images.

I didn’t love the viewfinder. Although it is impressively large and does an okay job of estimating the view of the 15mm lens, the edges of the frame were not clearly defined making it difficult to fully realize how much of what you are seeing will be captured on film, and even before you get to the edges, there was significant distortion. Looking through the viewfinder is somewhat like looking at a funhouse mirror where everything is blown way out of proportion. I understand why a camera like this couldn’t have a through the lens viewfinder, but upon hearing that the viewfinder is made of seven pieces of glass, I was surprised at how much distortion there was.

I wish the camera would have included a self-timer as it would have allowed the photographer to include themselves in large group photos in tight spaces, plus having a self-timer is always useful for long exposure photography in low light to eliminate body shake from pressing the shutter release. This is even more strange as the original Contarex had one. Perhaps Zeiss-Ikon knew the camera’s price was already reaching astronomical heights and wanted to do whatever they could to keep prices from getting any higher.

I spent most of this section of the review talking about the lens, because once you get past that, there’s not much else to say. Like the Hasselblad SWC, this is a camera body built around a lens. After loading in film, choosing a shutter speed, and advancing the lever, there’s no other steps needed. Just point and shoot!

The Zeiss-Ikon Hologon Ultrawide is an interesting….tool. It is not entirely accurate to call it a lens as there’s certainly more than just a lens here, but I don’t know if calling it a camera is right either because everything beyond the lens is only there to just use the lens. Whatever you want to call it, the Hologon Ultrawide is unlike any other photographic tool I’ve handled. Its looks, shape, ergonomics, viewfinder, and results are all special.

When new, this tool was beyond the reach of most photographers, even many professionals who could afford a professional SLR like a Nikon F. Even today, with so few made, collector prices on these cameras are still beyond the means of most normal film enthusiasts. That I had a chance to shoot one is amazing and something I’ll always cherish. Of any camera in my collection, I think this one will remind me of Kurt the most because of the timing of when I got it and how highly he spoke of it before sending it to me. Thanks Kurt!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Hologon_Ultrawide

“[…] rectilinear ultra wide angle lenses started to appear. By the mid 1960s, options included Minolta’s 18mm f/9.5 Rokkor”

-> The Minolta UW.ROKKOR-PG 18mm f9.5 is a fisheye, not rectiliniear. I have one… It was later replaced with the 16mm/2.8 fisheye. I guess when it came out, the term fisheye wasn’t that common and so they just called it ultrawide (UW).

Thanks for the catch, I have made the correction. I was repeating something else I had read! 🙂