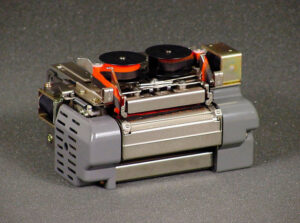

This is an Epson R-D1, a 6.1 Megapixel APS-C digital rangefinder camera designed by the Seiko Epson Corporation and built by Cosina of Japan between the years 2004 and 2007. The Epson R-D1 is historically significant as it was the first ever digital rangefinder camera and features a body with an almost film like user interface, including an optical rangefinder, shutter cocking lever, and a mode dial that looks exactly like a rewind knob on a film camera. The Epson R-D1 uses the Leica M-mount and was a high end camera upon its release, marketed towards Leica shooters who wanted to experience digital photography for the first time while still maintaining a very film like experience. The R-D1 received two minor updates throughout its life before the line was discontinued in 2014, an amazing 10 year run.

Sensor Type: 6.1 Megapixels APS-C Charge Coupled Device

Storage: 1x SD Card (1 GB Maximum)

File System: JPG, RAW (ERF Format)

Lens: 50mm f/1.4 Leica Summilux-M coated 8-elements in 5-groups

Lens Mount: Leica M Bayonet

Focus: 2.5 feet / 0.7 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder, 28mm / 35mm / 50mm Adjustable Frame Lines, 85% Field of View

Shutter: Electronically Controlled Vertically Traveling Metal Blade Shutter

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/2000 seconds

Exposure Meter: TTL Shutter Surface Direct Center Weighted Averaged Metering

Battery: 3.7v 1500 mAh Li-Ion Battery (Model EU-85)

Flash Mount: Hot shoe Plus PC Port M and X Flash Sync, X-Sync 1/125

Weight: 925 grams, 595 grams (body only)

Manual: https://files.support.epson.com/pdf/rd1___/rd1___u1.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Epson R-D1 was the world’s first and one of only a very small number of digital rangefinders. Built by Cosina for Seiko, the parent company of Epson, using the lens mount and with the build quality of a Leica, the Epson is an amalgam of analog in digital. The camera is strange by today’s standards but has excellent ergonomics, and despite only a 6.1 megapixel sensor, takes wonderful photographs. These cameras are difficult and expensive to find today, but if you can find one in good working order, are really fun and cool cameras to use. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for incomparable feature set, the most analog digital camera ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

At a high level, the brands Epson and Seiko don’t immediately register as a maker of fine digital cameras. If you’re like most people and you associate Epson with copiers, scanners, and printers, and Seiko with watches, you wouldn’t be wrong, as both companies have a long history of making excellent products in those categories.

At a high level, the brands Epson and Seiko don’t immediately register as a maker of fine digital cameras. If you’re like most people and you associate Epson with copiers, scanners, and printers, and Seiko with watches, you wouldn’t be wrong, as both companies have a long history of making excellent products in those categories.

For the photographic industry, Seiko has a ricer history as they produced a huge number of leaf shutters for Japanese companies under the Seikosha name. Cameras by Minolta, Yashica, Kowa, Aires, Ricoh, and many others used Seikosha shutters at one time.

The history of Seiko starts all the way back in 1881 with a man named Kintarō Hattori who started a small shop in his home repairing watches and selling replacement parts he created himself. Kintarō Hattori did this himself for a couple years before relocating to Tokyo in 1887 and incorporating his company as K. K. Hattori Tokei-ten which literally translates to Japanese Watch Shop.

Over the next decade the company was very successful, and in 1892 formed a manufacturing division with the name Seikōsha to manufacture clock and watch movements. The name Seikōsha translates loosely to “precision house”, which makes sense given the products they built.

In 1930, the Seikōsha factory built their own camera shutter called the Magna which was a copy of the German Vario shutter. The Magna was used on a large number of Japanese cameras, primarily those made by Kuribayashi (later Petri) and Konishiroku (later Konica). The company would eventually create a large number of other shutters like the medium format Licht shutter, and eventually the company’s own Seikosha shutter, which was originally a copy of the German Compur shutter, but would later evolve into its own design.

In 1932, a manufacturing branch of K. K. Hattori Tokei-ten would merge with one of the company’s subcontractors, Katsuma Kōgaku Kikai Seisakusho to form an all new company, Tōkyō Kōgaku Kikai K.K. exclusively to make cameras and lenses. This new company’s first products were simple folding cameras called the Lord and later the Minion. After World War II the company would be a lens supplier to many other Japanese companies with their Simlar and Topcor lenses. Tōkyō Kōgaku would produce multiple different 35mm and medium format cameras, but would see its greatest success with their Topcon SLRs. The company would eventually be known by Topcon, their most successful product, but due to declining sales in the 1970s, would cease camera making activity in 1980.

In addition to its many manufacturing divisions, Hattori Seikō also had a retail and distribution business as well. In the 1930s, Hattori Seikō was the exclusive distributor for the Japanese brands, Gelto, Lord, and Zenobia. Also at this time, they imported German brands like Zeiss-Ikon and Certo.

In May 1942, Hattori Seikō’s Seikōsha factory was evacuated to Nagano, Japan to shelter it from wartime activity. This new factory was given the name K. K. Daiwa Kogyo and was led by a Hattori Seikō employee named Hisao Yamazaki and continued to produce watches and other timepieces during the war. After the war, production at the Nagano factory continued even though the original Seikōsha factory was back in operation. Over the next decade, both factories worked in parallel until 1959 at which time K .K. Daiwa Kogyo took over the Seikōsha factory and changed its name to K. K. Suwa Seikōsha.

By the mid 1960s, K. K. Daiwa Kogyo had expanded into electronic circuits and semiconductor technology and n 1964 build Japan’s first table top quartz clock. In September 1968, the company released the EP-101, the world’s first compact lightweight digital printer. The EP-101 was used for print outs from desktop calculators and other early microprinters. It consumed one twentieth the power of comparable printers and was much smaller, expanding the printing abilities into market segments never before possible. The EP-101 was a tremendous success and led to the development of other smaller, and eventually more advanced printers.

In 1975, K. K. Suwa Seikōsha’s printer lineup was given the name “Epson” with the name supposedly meaning the “son” of the EP. By 1982, the company officially changed its name to Epson Corporation. Three years later, the company would come full circle and merge with K. K. Seikōsha to become the Seiko Epson Corporation, the name the company still uses today.

With such a long and rich history producing such a wide variety of products both in and out of the camera industry, and with Japan’s consistent aptitude making cameras, it was strange that it would take the company so long to make their own camera. In fact, it would take almost 20 years after the Epson and Seikōsha merger for the company to try their hand at making a camera.

Unlike other companies who cautiously jumped into the camera making business with a simple or unambitious camera, Seiko Epson went all in, creating the Epson R-D1, a digital camera with an optical rangefinder and using the Leica M bayonet mount. Although digital cameras had been around for more than a decade prior to the R-D1’s release, mass adoption hadn’t yet occured, so to create a premium item using the best lenses out there, with a feature set that was far beyond the needs of the amateur photographer, the R-D1 was a curious choice.

Seiko Epson had a tremendous amount of industrial knowledge, but had never made a camera, so for the construction of the R-D1 they turned to another Japanese company, Cosina, to build it. Cosina had already been making rangefinder cameras using the Voigtländer and Rollei names, which they had licensed from the German retailed Ringfoto who owned the brands. Cosina made Voigtlander Bessa and Rollei cameras like the Rollei 35 RF were produced from 1999 to 2013 and were seen as the last hurrah for interchangeable lens film rangefinders.

When the Epson R-D1 was released, the photographic press marveled at the strange marriage of old and new. A rangefinder camera in the style of the Leica M-series, build in a rugged magnesium and aluminum alloy body, but with a 6.1 megapixel sensor and support for memory cards up to 1 GB was completely new territory for pretty much everyone as no one had ever done it before. The digital cameras that were quickly gaining popularity were either of the point and shoot or DSLR variety.

Like the Leica lenses it was designed to use, the R-D1 was a premium camera that carried a premium price. In 2004, Epson listed the retail price of just the body at $3000. Actual street prices were likely 20% less, but even at the MSRP, when adjusted for inflation, compares to an astounding $4800 today, and that doesn’t even include a lens!

Whether anyone could, or was willing to afford it, there was quite a bit of excitement from the photographic world upon the Epson R-D1’s release. Not only was it the first ever digital rangefinder, but it also was built to a very high quality standard and appealed to existing Leica customers. At the annual 2004 TIPA (Technical Image Press Association) meeting, which awards the best photographic products available in Europe, the Epson R-D1 won an award for best “Prestige” camera.

Reviews like the two above from the Mar/Apr 2005 issue of American Photo and November 2006 of HWM Magazines reviewed the R-D1 and its successor the R-D1s with great praise. Both articles unanimously praised the image quality from the camera and the successful blend of old and new. Surprisingly, the inclusion of a lever to manually cock the shutter wasn’t loved, even by those used to film cameras.

Overall, the Epson R-D1 was perceived as a new take on what the digital revolution might bring. Although Leitz would release the Leica M8 digital rangefinder less than 2 years after the R-D1, this wasn’t a market segment that was hugely popular. The desire of most amateur and professional photographers was either through the lens viewing or total automation, with nothing in between.

The Epson R-D1 wasn’t a failure though as two follow-up models were released, the R-D1s which was the same physical camera, but with an updated firmware that added the option for Adobe RGB color space and support for RAW+JPG quality modes, plus a few other minor software tweaks. The firmware update included in the R-D1s could be loaded into the original R-D1 effectively turning them into the same camera.

A third version, released only in Japan was called the R-D1x and did have some hardware changes, the most significant was the replacement of the swiveling 2 inch viewfinder with a fixed 2.5 inch one. Other changes were support for new SDHC flash memory cards which could support more than the original models 1GB limit, and a provision for an attachment handgrip. Despite being released 5 years after the original model, the R-D1x used the same 6.1 megapixel APS-C sensor and offered no other additional features.

It is not clear when production of the R-D1x ended with some sites suggesting 2013, but this could also be the date in which warranty support ended on the cameras. According to an Epson press release, a total of only 10,000 cameras were produced throughout the run of the R-D1 and R-D1s but it is not clear if this also included the R-D1x.

In the years following the R-D1’s release, Epson would never again make another digital rangefinder or any prestigious camera, but in a surprise 2022 article, the company revealed that plans were in motion for a successor, however it was scrapped likely due to Epson’s lack of market share in the digital camera market. Renders of what a replacement for the R-D1 might have been were posted online.

In the renders above, it is clear the camera was an entirely new design and would no longer have an optical rangefinder and eliminated the film advance lever. The body design looks more compact than the Cosina body of the original, and the lack of any viewfinder of any kind suggests a mirrorless system with an EVF. The lens in the render says “Epson Zoom Lens” which could suggest Epson would have included their own “kit” lens, but it is not clear what lens mount is there. The release button is in the same position as, and looks very similar to the Leica M mount, so it is plausible that the lens mount would be the same. The shutter speeds go up to 1/4000 which means a new shutter, possibly something from a current generation DSLR or mirrorless from another vendor could be in play. Finally, the large rear LCD does not appear to swivel and has a directional pad, keeping in touch with the designs of digital cameras this unnamed camera might have competed against.

It is difficult to really know what a follow up to the Epson RD-1 might have looked like. The drawings above could suggest that something was in development, or these could be artist’s conceptual renderings of a design that never began production. Exactly how far Epson got is not clear, but from what little information exists. my best guess is, “not far”.

Epson would produce other digital cameras under their name, including the consumer friendly “PhotoPC” line, but all were inexpensive point and shoots. The RD-1 would be the company’s only attempt at a luxury or high specification camera, which is a shame as they did a great job with it. I wonder what the follow up might have looked like or other DSLR or digital mirrorless cameras had they made them.

By far, if you are into photography and own an Epson product, it is going to be one of their printers or scanners. In fact, on this site, since 2018, any film I’ve shot and developed myself was scanned either on an Epson V550 or V750 Pro scanner.

Today, Epson and Seiko are both recognizable names, but not as camera makers. Most collectors are aware of the Epson R-D1 and its submodels, but few have seen one. With less than 10,000 ever made, and prices well into the several thousands of dollars when new, very few people have shot one. Prices today on the used market are at a point where they’re more attainable than they once were, but that they’re from a very small niche of optical rangefinder digital camera, there simply aren’t a lot of people who would actively shoot one of these, which is a shame as the Epson R-D1 is a super cool camera. It has a very good build quality, excellent viewfinder, a unique viewfinder, and supports the Leica M-mount. There is a lot to like, so if you find one for a reasonable price in working condition, you owe it to yourself to check one out!

My Thoughts

If I were to tell you that I had a Japanese made digital rangefinder with analog watch dials that was sold under a brand name more well known for printers and scanners, you’d probably think I was crazy. If you actually knew what I was talking about, then you’d know I could only be referring to one camera (okay, technically three, but they’re so similar), the Epson R-D1.

The Epson R-D1 is one of the most strange and glorious cameras I’ve ever held, used, or seen. I was vaguely aware that they existed until I had a chance to get one for a price I could not refuse.

At first glance, the R-D1 bears a strong resemblance to the Voigtländer Bessa 35mm rangefinders built by Cosina throughout the early 2000s, and rightfully so as the body and actual construction was done by Cosina for Seiko, the parent company of Epson. The camera body has a very high quality feel to it, almost better than the Bessas. The R-D1 uses the Leica M-mount so it can mount any number of Leica M rangefinder lenses, but here I have the Leica Summilux-M 50mm f/1.4 which is drool inducing by itself.

The black painted body has a textured finished and the body covering is made of thick rubber that is very easy to grip and feels excellent in your hands. Unlike many rubber backed cameras from this era, this particular R-D1 is not exhibiting any signs of degradation or stickiness. Unlike some other black bodied cameras in which there are still some chrome accents like the flash shoe, dials, or film advance lever, the Epson R-D1 is entirely blacked out, which gives it a really cool, almost custom look. The body itself weighs a not insignificant 595 grams, but adding the solid metal and glass Summilux-M lens ups the total weight to 925 grams.

In the world of digital rangefinders, the Epson R-D1 really only has one competitor, the Leicas M8 – M11, which came two years after the Epson, and although the two cameras share some similarities, are very different. Both the Epson R-D1 and Leica M8 are uncommon cameras, but wouldn’t it look good to see a photo of them together? Oh wait a minute…

The Epson R-D1 is definitely a digital camera, but by looking solely at the top plate, you wouldn’t know that because off to the left is what looks like a totally normal film rewind knob, as you’d expect to see on a Leica M film camera or any number of other 35mm cameras. Even though it looks like a rewind knob, this dial is actually the mode dial that is used to rotate through options in both the menu and through various settings of the camera, but more on that later.

Next is a three position lever that lets you select between 50mm, 28mm, and 35mm frame lines. Since the R-D1 has an optical rangefinder like a Leica M1 through M7, you cannot see through the taking lens and the Epson R-D1 predates Live View, so there is no way to compose your image in a way where you can see what will be captured. In the center is a regular looking flash hot shoe, and then what can only be described as an analog watch dial. This deserves its own section so I’ll skip it for now.

To the right of the analog dial is a combined shutter speed, ISO speed, and EV compensation dial which surrounds the cable threaded shutter release. Manual shutter speeds from 1 to 1/2000 seconds plus Bulb are available, but when turning the dial to an AE position, you put the camera in aperture priority auto exposure mode. With the mode dial in the AE position, the dial becomes locked and will not move unless you press and hold a small button below and to the left of the dial. On either side of the AE position are positions to add EV compensation + or – 2 stops. The EV compensation dial works with AE mode only and cannot be chosen in manual exposure mode. For changing the ISO speed, lift up on the outer edge of the dial and rotate it. A small window next to the Bulb setting will show ISO settings from 200 to 1600.

Finally, there is the film…err I mean digital shutter cocking lever, with integrated On/Off switch above it. The Epson R-D1 has a power save mode, so even if you forget to turn the camera off, the camera automatically powers down after a set amount of minutes. In my testing of this camera, I left it On for well over a week and the battery was still fully charged, so while there are probably good reasons to turn it off, forgetting to turn it off, is not the big deal it is on most other digital cameras.

The presence of what looks to be a normal film advance lever on a digital camera is certainly strange, and one of the Epson R-D1’s greatest weakness or biggest strengths, depending on how you look at it. From a practical standpoint, there is no real good reason for a digital camera to require you to manually cock the shutter. This process absolutely slows you down, and if you’re anything like me, once you know you’re shooting digital, it is very hard to remember to advance the lever in between each shot. I lack the understanding of psychology which would explain how I have no problem winding a lever on a film camera, but when I have to do the exact same thing on a digital camera, it feels so strange. Then again, it is freaking cool! For anyone looking for a hybrid film/digital shooting experience, this is it!

Back to the large analog watch dial, which is without a doubt, one of the coolest features I’ve seen on any camera, digital or otherwise. There are many aspects of this cameras design that are clearly from Cosina. The camera also has more than a passing resemblance to a Leica, even using its lens mount. But the analog dial is entirely the word of Epson’s parent company, Seiko. In fact, the movements within this dial are straight out of a Seiko watch parts bin.

Instead of telling time, within this circle are most of the settings you’d typically see on a digital LCD, such as number of exposures remaining, white balance, image quality, and battery level. A large white needle extending from the very center to the edge, points to a ring around the dial indicating exposures remaining, starting with the letter E for empty, then counting up to 10, and then skipping to 20, 50, 100, and 500. As you shoot the camera, the analog needle moves, pointing to the number of exposures remaining. That it doesn’t give you an exact readout over 10, and has an upper limit of 500 is hardly the dealbreaker it might see, as this is an older digital camera, and even with a 1GB memory card, can still hold a lot of images, and does it really matter to know that you have exactly 209, 117, or 56 exposures? No, you just want to get an idea of how close to zero you are, and this dial accomplishes that.

From left to right, the first needle indicates white balance and has an A for Auto, and 5 icons indicating Sunny, Shade, Cloudy, Incandescent, and Fluorescent. Next is the battery level with E and F like a gas gauge, and finally image quality with three settings for RAW, High, and Normal. When selecting RAW, the camera can optionally save JPGs along with the RAW files using an option in the camera’s setup menu, or you can choose RAW only. Unlike other cameras, the High and Normal Quality settings do not affect the compression of the file, rather the file size with High saving a 6 megapixel 3008×2000 image and Normal saving a 3.3 megapixel 2240 x 1488 image. According to the user menu, JPG compression is fixed at 1/4, whatever that means.

Perhaps the coolest thing about the dial however, is that upon turning the camera on and off, all of the needles reset and do a sweeping motion to get back to where they were. This small little detail is super cool and feels so out of place on a digital camera.

Flip the camera over and the base has the door for the rechargeable 3.7v Epson EU-85 Lithium Ion battery, a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, and a sticker reminding you that the camera is by Epson and was, in fact, Made in Japan. I was fortunate that the original battery still holds a decent charge, despite being nearly 20 years old, but I was pleased to see that there are still aftermarket versions available on Amazon for $15.

The camera sides are symmetrical and have rounded edges with slight angles which make gripping the camera very comfortable. On each side are chrome metal strap lugs, which is a very welcome feature, considering the value of not only the camera, but the lenses you’re likely to attach to it, walking around with this camera and no strap would be a very bad idea.

Hidden behind an unmarked door on the camera’s right side are both the SD card slot and a USB port for connecting the camera to a computer. The first time I picked up the camera, it was not obvious this door was here and it wasn’t until I RTFM that I discovered it. In addition, the first time I looked in here, I didn’t even realize it had a USB port as mine still had a rubber plug protecting the port. You can see it in the previous image to the left of the card slot. The USB port is a mini-USB B port which was common back when this camera was new.

For the memory card, the original Epson R-D1 and R-D1s only support SD cards up to 1GB. Only the Epson R-D1x supports cards larger than 1GB, but with the low resolution of the camera’s 6 megapixel sensor, you can still fit a good number of images on the card. At the highest JPG quality, the average image size is around 3MB which means you can easily fit over 300 images on a 1GB card.

Around back, in the upper corner is a large round eyepiece for the optical rangefinder. Looking through the viewfinder, the camera looks almost exactly the same as a Leica M film camera or the Cosina Bessas. Opposite of the eyepiece is an unlabeled AE lock button, and a momentary two position switch for changing white balance and image quality. In order to change either setting, you must press and hold the lever in the direction of either setting, while also rotating the mode selection dial which looks like a rewind knob on the top plate. Doing this moves the analog needle for either setting to one of the available options.

In the middle of the back is the best indicator that this is a digital camera, the 2 inch 235,000 pixel LCD screen and 5 mode buttons. The screen is hinged and folds out 90 degrees from the body, allowing you to rotate it 180 degrees so that when you fold it shut, the LCD screen faces toward the body. When you do this, the backside of the LCD has a handy APS-C crop sensor conversion chart, showing you the focal length of common film lenses and what they would be after the crop factor. Other than seeing this chart or protecting the LCD, because the Epson R-D1 lacks Live View, there is no way to use this screen like you would on modern digital cameras with a swiveling screen at waist level, or for selfies. This camera is the original R-D1, but a later update to this camera called the R-D1x replaced the swiveling 2″ screen with a fixed 2.5″ screen.

The five mode buttons to the right of the LCD activate both the main settings menu and the ability to review previously shot images. Each of the buttons are indicated with only an icon, whose function is not always obvious. The menu system is also rather rudimentary which could be forgiven as most early digital cameras hadn’t yet worked out how a digital camera’s menu should work, but you’ll definitely need to RTM at least once to familiarize yourself with the menu here. I’ll cover the menu system later in this review, but for now options are here to choose between color and monochrome, change color space, RAW+JPG or RAW only, adjust the clock, numbering sequence, adjust the power save timer, assign a custom function to the User button, and format the SD card.

Up front, the Epson R-D1 looks like a Cosina/Leica hybrid with the Leica M-mount in the center and a stepped viewfinder containing the main viewfinder window, frosted frame lines window, and smaller rangefinder window. Like all Leica M cameras, the lens release is at the 9 o’clock position around the lens. Press and hold this button while rotating the lens counterclockwise to dismount and clockwise to mount. Despite the Epson R-D1’s film roots, the camera lacks a self-timer.

I cannot prove this, but based on the various other Cosina made rangefinders from the 2000s, it seems to me that the same, or very similar designs were used in the Bessa, Rollei, and Epson models. Each camera has an extremely bright and lifesize viewfinder with high contrast framelines with automatic parallax correction and a large rectangular rangefinder patch. Compared to a Bessa R2C I have, the Epson’s rangefinder patch has more squared off corners than the rounded ones on the Bessa, but otherwise give just as good of a double image as any rangefinder I’ve ever seen.

Three different sets of frame lines are available based on the position of the switch on the top plate of the camera. You have your choice between 50mm, 28mm, and 35mm. No telephoto options are available, however it is worth noting that the labels of 50, 28, and 35 are for Leica M film lenses. When mounting a Leica 50mm lens to the camera, set the position for 50mm, and the frame lines will show the correct 1.5x cropped image, so in reality, with the viewfinder at the 50mm setting, it looks more like what a 75mm frame line would look like, and the 35mm position is more like what a 50mm looks like. This is important to know that the viewfinder takes care of the crop sensor conversion for you.

In addition to frame lines, the Epson R-D1 has a projected shutter speed scale in red near the bottom of the viewfinder. This scale is not visible unless the camera is powered up and the shutter release half-pressed down. Once the scale is visible, it will remain lit up for about 15 seconds or until you fire the shutter, whichever comes first.

The scale works in both AE and manual exposure modes. With Automatic Exposure on, a half-press of the shutter release will illuminate the shutter speed the camera will select once you press the shutter release the rest of the way. You can alter the meter’s chosen shutter speed by choosing a different f/stop on the lens or using the EV compensation on the shutter speed dial. In manual exposure mode, the selected shutter speed will light up in red, and the shutter speed recommended by the meter will blink. This allows you to see both the recommended and your chosen shutter speeds, in a sort of “match LED” display. The display does not like up with the shutter in Bulb mode.

It is clear, that despite being known as a maker of printers and scanners, Epson’s first foray into digital cameras was no half hearted attempt. Epson aimed to make a splash with a precision camera that was made to the highest quality available, used the best lenses available, and had a feature set that no one else did. The Epson R-D1 is a solid camera with both excellent build quality and ergonomics. With the option of a huge library of world class lenses that would work with it, the Epson R-D1 was a serious camera with a serious price tag. Of course, its 6.1 megapixel sensor, optical viewfinder, and tiny rear LCD seem primitive by today’s standards, how well does it actually hold up? Can a camera that when new cost the equivalent of the price of a used car still hold up nearly 20 years later? Keep reading…

My Results

A distinct advantage to reviewing digital cameras compared to film cameras is that the testing process goes much faster. There’s no deciding what film to load and whether or not it will be compatible with the time of year, weather, and scenery I plan on shooting. As with all digital cameras, the economy of more shots without having to worry about wasting film means I could take more candid photos. Finally, not having to develop or scan the rolls of film into the computer before I get to see how the camera performed means almost instant results. The one challenge I had to overcome before shooting the Epson was finding a memory card old enough to work in it as it has a maximum supported capacity of 1 GB. Thankfully, I was able to locate one which I had in my “junk drawer”. I put it in, set the camera to AE mode and took it with me in late summer of 2023.

Any camera with a Leica M lens mount, regardless of who made the camera, has the advantage of supporting a large selection of some of the best lenses ever made. The Epson R-D1 is no exception, so for my test, I set the bar pretty high and went with both the 50mm and 35mm f/1.4 Summilux-M. For the images of the camera in this article, I had the 50mm lens mounted, but for a majority of the gallery shots, I switched to the 35mm to counteract the crop factor. The Epson R-D1 has an APS-C size sensor which means 50mm lenses compare to 75mm on the Epson, and the 35mm compares to about a 52mm lens. I used the 35mm lens as it most closely resembles what a 50mm prime would be like on a film camera.

Awesome. These images look awesome.

Whenever shooting early digital cameras with less pixels, there is always the worry of whether or not the loss of data will negatively impact the images they make. Much like the era of half-frame 35mm, a smaller image means less detail, so to counteract that, you need a sharper lens.

Both Leica Summiluxes are notoriously very sharp with no optical deficiencies, allowing the 6.1 megapixel APS-C sensor to really shine. For context, nearly every review on this site features digital images of the cameras I am reviewing. Over the years, I’ve used combinations of a Nikon D7000, Fuji X-T20, Sony a7II, and now a Nikon Z5, all of which have significantly higher resolution sensors than the Epson R-D1, but in every case, I resize the images down to 3000×2000, which coincidentally, is nearly the same as the native resolution of the R-D1’s 6.1 megapixel sensor. So when you look at a pretty picture of the Epson taken with my Nikon Z5, it is displayed on your screen at the exact same resolution that this camera shoots, and if I’m being honest, I cannot see much of a difference in quality.

For the entirety of the gallery above, the ISO sensitivity was set to 200, which is the camera’s lowest setting. I wanted to do a separate test for ISO in a more controlled environment, so for that test I setup three different scenes, two indoor shot at f/2 and one outdoor shot at f/8 and the camera in AE mode for all three. I changed the ISO setting between 200, 400, 800, and 1600 as indicated in each image.

Having shot other early digital cameras, I’ve seen significant drops in quality at every step of raising the ISO. I remember an early Canon digicam I had around 2005 which produced images at ISO 1600 that looked terrible, so I expected similar results from the Epson.

To my amazement, I thought that all four ISO settings delivered usable images. At full screen on my computer monitor, it was difficult to see a difference between ISO 200 and 400. At 800, there is an ever so tiny amount of noise, but you have to zoom in to see it. Only at 1600 could I see the noise without zooming in. In use, I was extremely impressed with the image quality at all four ISO settings, and with a fast f/1.4 lens and the camera at ISO 1600, I could get good looking hand held shots in very low light without motion blur.

The build quality of the camera is extremely high. Having shot this, a digital Leica M8, and other Cosina built film rangefinders, the Epson has a build quality much more in line with the Leica than any Bessa. The camera is very solid and is quite a bit heavier than a modern digital camera might suggest, giving it a luxurious, premium feel. The buttons and controls are all nicely designed with good ergonomics and move with a level of precision not found on cheaper cameras. I loved the choice of using the rewind knob as the menu dial. While not in the most intuitive location, using it was not a challenge and had very satisfying click stops as you rotated it. The viewfinder is as large and bright as any Leica M-series rangefinder I’ve used, and seeing the bright LED shutter speeds was easy, even outdoors. While shooting, you can easily control exposure and focus without ever lowering the camera from your eye.

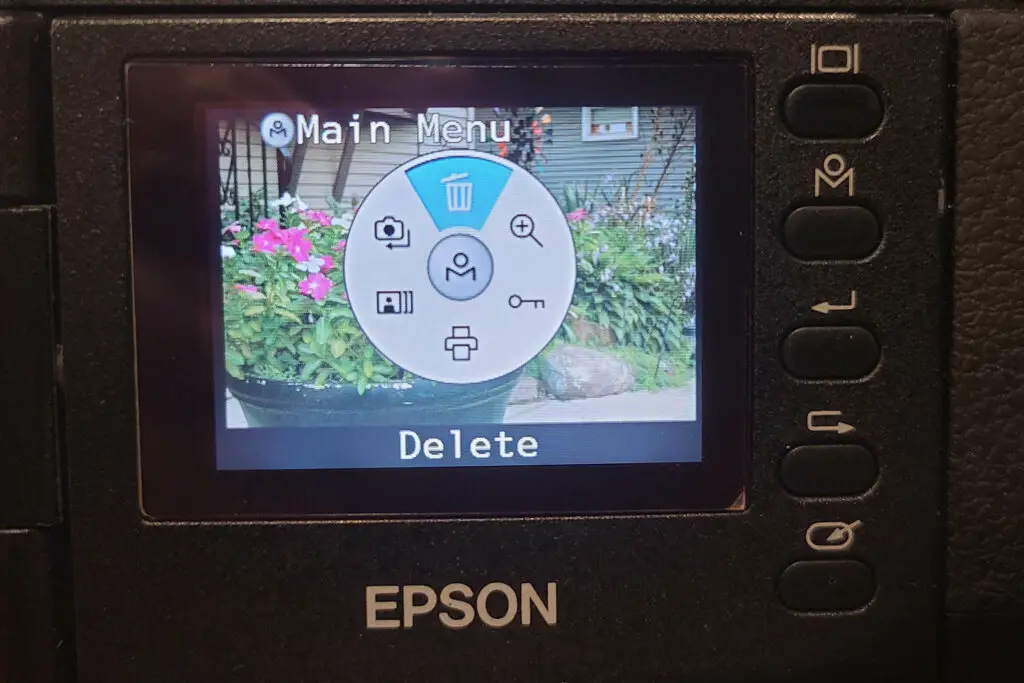

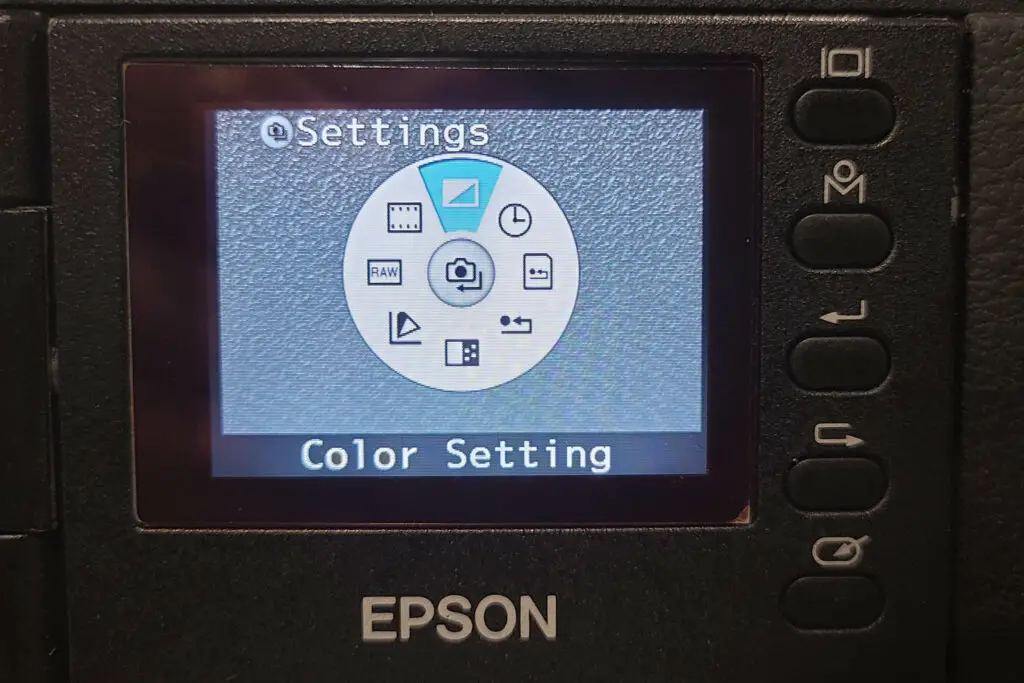

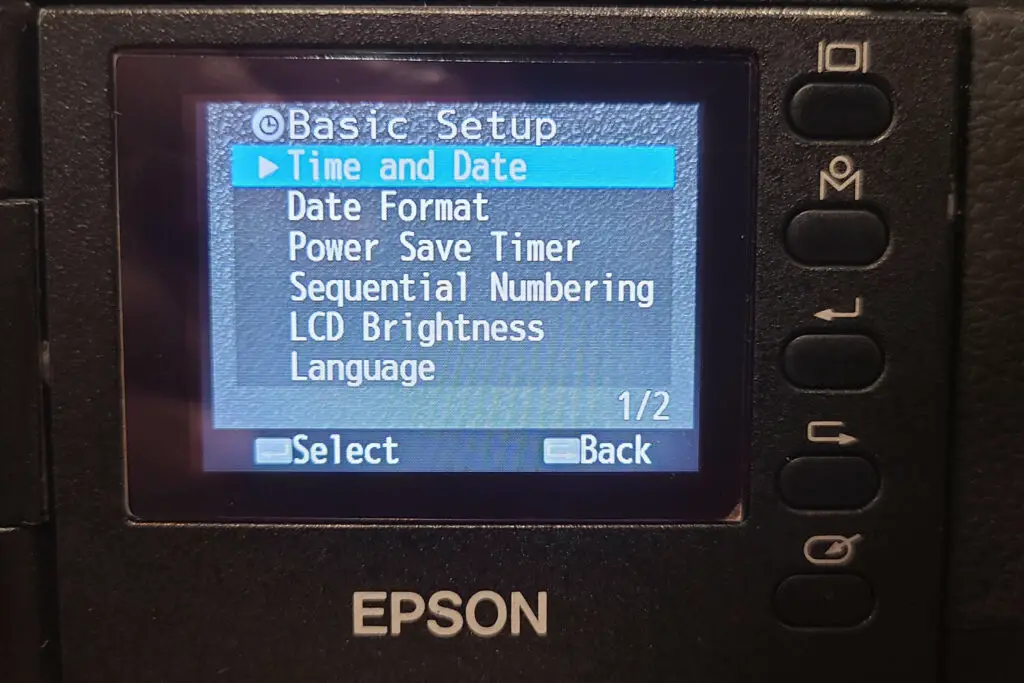

There is certainly a lot to like about the Epson R-D1, but one thing I really disliked was the menu system. I can be forgiving of an early digital camera made by a company who hadn’t yet perfected how an LCD menu should work, but the one here isn’t very good. For starters, the 5 buttons on the back of the camera have only icons to indicate their function and unfortunately, the icons don’t make a lot of sense. Pressing the top button turns on the LCD to review a previous image, but then you need to press the second button of the M with a circle above it to get to the menu. You cannot get to the menu directly with the screen off. The next to are an Enter and Back button, and the button button of an oval with an arrow pointing to it, is some type of custom function button.

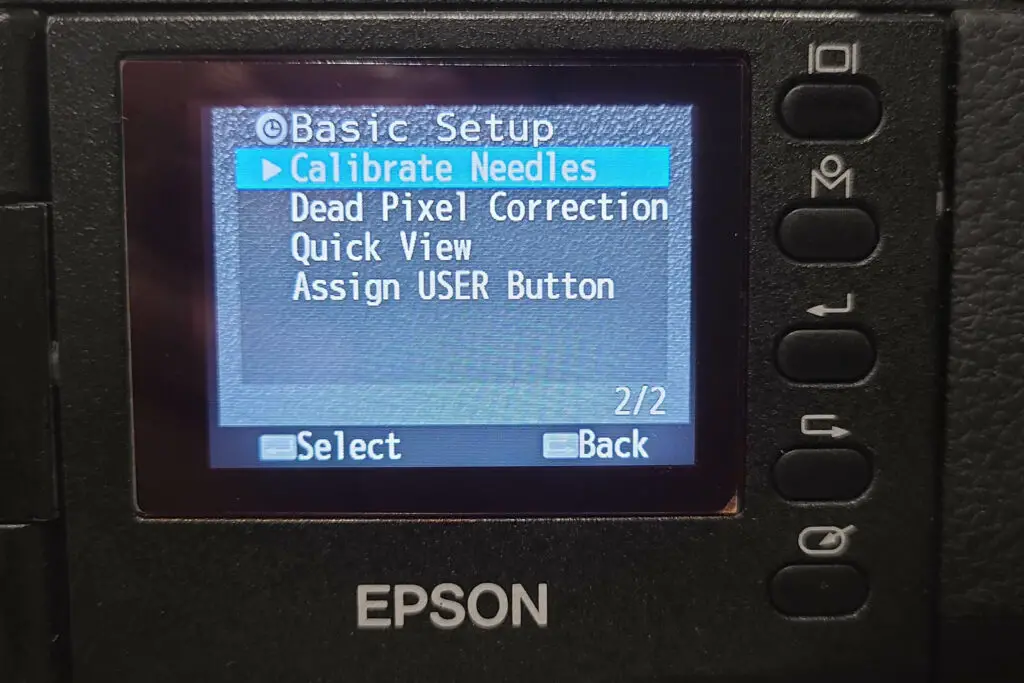

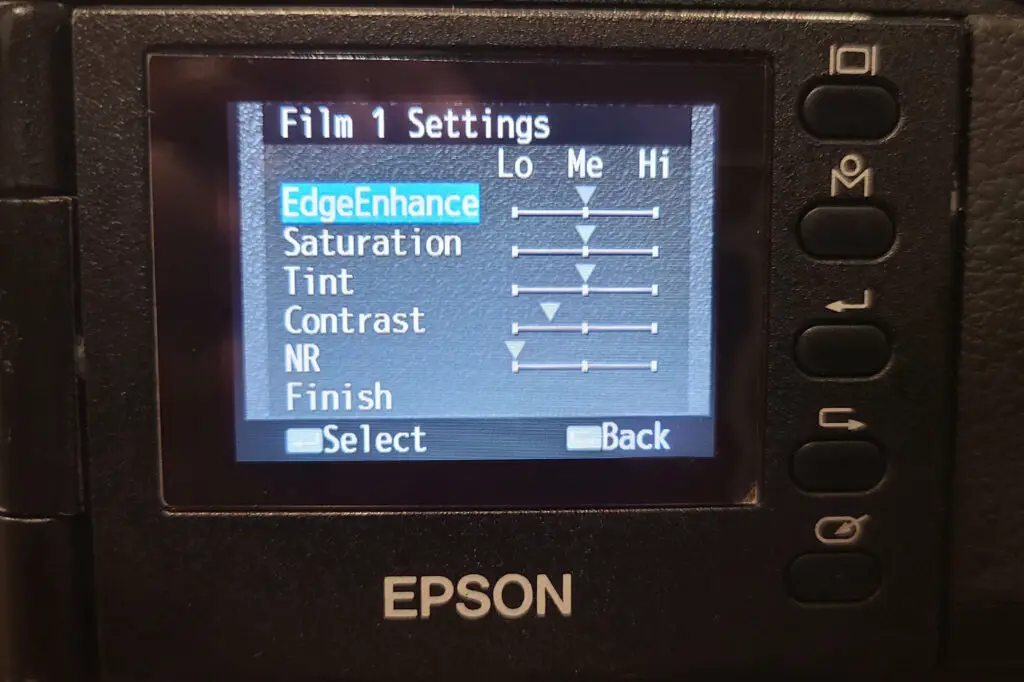

The gallery below shows several screenshots of the LCD, the first shows an image preview and the other five show various menu options including the Basic Setup menu.

Once inside the menu, more icons are arranged in a circle, which thankfully are labeled at the bottom to tell you what they are. To get into the camera’s settings, the icon of the camera with a right angle arrow beneath it opens a Settings menu. This menu gives you control over things like Color Space, RAW mode (assuming you have the new firmware), formatting the SD card and a few others, but yet another menu called “Basic Setup” is included here with more options, one of which is changing the camera’s language. This is important to know as when I acquired this camera, it was entirely in Japanese, and finding this setting took me a while. I am unsure if this camera was previously set to Japanese and left that way, or if after so long without a battery, the camera defaults back to Japanese. Either way, this is where you need to go if you need to change the camera to English.

Using the menu is definitely not intuitive, although I did like the feel of using the mode dial on top of the camera to cycle through options. Basic functions like magnifying a stored image, or changing the LCD brightness are unnecessarily complex. For more critical features like White Balance, Quality, and ISO setting, these are done with the camera’s physical controls, and not the LCD.

While I didn’t care much for the menu system, the good news is you don’t need to use it very often as all of the critical digital camera functions are accessed via the analog needles on top of the camera. You could go the entire lifetime of using the Epson R-D1 without ever going into the menu. This is a big plus considering everything else is great.

Over the past decade, there has been a retro shift in styling for premium digital cameras. Companies like Fuji, Olympus, and Nikon have produced a large number of digital mirrorless and SLR cameras that have styling cues from generations before. Pentax made a digital MX premium digital camera, Nikon’s Z series, including the ZF and ZFc look like a Nikon FM with a digital sensor, and Fuji’s X-series of cameras have mechanical knobs for shutter speed and EV compensation with an overall retro flair. Beyond styling, there has been a big push in the crowdfunding segment with devices like the “I’m Back” which turn actual film cameras into digital cameras with sensors that replace the film door. While none of these options faithfully recreate the shooting experience of a film camera, they at least suggest that many people really love the idea of a hybrid film and digital camera.

For me, the Epson R-D1 is that camera. It is a perfect blend of an analog film camera and a digital camera, and despite “only” having a 6.1 megapixel sensor, it shoots images that rival the sharpest film emulsion and drum scans of a 35mm camera. While the shutter cocking lever does slow you down a bit and the optical rangefinder doesn’t accurately frame the digital image, they work EXACTLY as they do on their analog film counterparts. The Seiko designed analog needles, while not truly necessary, add an element of analog coolness not found on any other digital camera.

Overwhelmingly, the Epson R-D1 is the best combination of a film and digital camera I’ve ever used, and perhaps anyone ever has. Other than the Leica M8, no other company made an interchangeable lens optical rangefinder digital camera. While the Leica M8 is a terrific camera too, it is a more of a pure digital camera, without any analog needles, a top plate LCD, and no advance lever.

Sadly, the Epson rangefinders are rare and very expensive. In addition, as with all early digital cameras, these cameras are approaching their 20th birthday, and like most other electronic cameras, are starting to suffer the perils of time much faster than an actual mechanical film camera would. I have no information about how many Epsons are still out there, or how many are in good operating condition, but I have to assume the answer is “not many” and every day, that number goes down.

So, if you are in the market for what is perhaps the purest digital camera with analog functionality, and you have very deep pockets, you should consider one of these before it is too late.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epson_R-D1

https://www.dpreview.com/articles/1924025521/epsonrd1

https://www.reidreviews.com/examples/r-d1.html

https://www.35mmc.com/23/03/2019/epson-r-d1-review-digi-film/

https://cameralegend.com/2022/05/02/the-epson-r-d1-202216-year-review/

https://luminous-landscape.com/epson-r-d1-opinion/

Wouldn’t the Leica M11 count as a digital rangefinder camera? Why only the M8? I can certainly use mine with the optical rangefinder.

Having never so much as seen an M11, I guess I should have clarified as including the Leica M8 (which I do own), and said “Leica M8 and up”.

Enjoyed the post. I have a couple of the Epsons, drifted away from them as digital took some huge leaps forward not because of any real problems. Their files made prints very comparable to shooting film if you stayed within an 8×10 print size and got your exposure right. Bought an M8 when they came out but wound up selling it. The last time i got the Epsons out i had problems with the rear LCD and havent found anyone here in US who will work on them. Are you aware of someone?

Jim, I am happy you enjoyed the post, but sadly, I am not aware of anyone who will touch these cameras. It is hard enough find qualified people to work on mechanical film cameras, but finding someone to do an early digital is nearly impossible. If you do find someone, please share!

I bought one of these brand-new when they first became available in late 2003. I wasn’t a rich person and it was, as I liked to say then, “the most expensive thing I ever bought that didn’t need license plates.” My photographer friends thought I was crazy to prefer it over my Nikon D100, but I had learned photography on rangefinder cameras and always gravitated toward them, so it had been exactly what I had been waiting for. 20 years later, the D100 and many cameras since are long gone, but I still have the R-D1 and still enjoy using it for personal photography… a pretty good return, I think, on my original $3000 expenditure!

PS — The photo caption says: “This is every single digital rangefinder camera ever made!” But… what, no Pixii?