This is a Fuji FP-1 Professional, a folding instant film camera made by Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd. in Tokyo, Japan starting in 1987. The FP-1 was part of Fuji’s Fotorama series of instant film products released in the 1980s. The FP-1 shoots ten 3¼ x 4¼” images on peel apart instant pack film which is no longer made today. Fuji was the last company to make its FP-100 and FP-3000 instant pack film, which it discontinued in 2016. Despite being considered a “professional” camera, its construction is pretty basic consisting of a mostly plastic folding body with a retracting bellows. The camera is entirely mechanical, with no exposure metering, no auto focus, and no automation of any kind. It has a coupled rangefinder and a leaf shutter capable of speeds from 1 to 1/500 seconds.

Film Type: Peel Apart Instant Pack Film

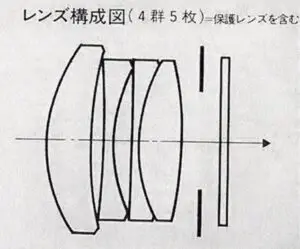

Lens: 105mm f/5.6 Fujinon coated 5-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 0.8 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder, 90% Field of View, 0.6x Magnification.

Shutter: Fuji Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: None

Weight: 1326 grams

Manual (in Japanese): https://mikeeckman.com/media/FujiFP1Manual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Fuji FP-1 Professional was Fuji’s first camera to shoot their new FP-100 peel apart instant film, which itself was based off Polaroid’s 660-series film. It is a very basic folding rangefinder camera, with a short list of features, but includes a good 5-element lens sure to get the most of the large instant prints it is capable of. While a huge number of customers at the time likely used a Polaroid camera to shoot the new film, the FP-1 Professional gave customers a new and reasonably well built option to shoot their new film and is one of the best ways to experience this film, if you are lucky enough to still have some. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.0 | ||||||

History

Fuji’s role in the development of the instant film industry is significant, yet largely unknown outside of Japan. Dating back to the early 1980s, Fuji has been a strong player in the instant film industry, out living both Kodak and Polaroid, the latter of which stopped producing their own instant film in 2009.

Fuji’s role in the development of the instant film industry is significant, yet largely unknown outside of Japan. Dating back to the early 1980s, Fuji has been a strong player in the instant film industry, out living both Kodak and Polaroid, the latter of which stopped producing their own instant film in 2009.

Fuji Instax film is the company’s best selling film product with year over year increases every year since its introduction in 1998. According to toyokeizai.net, all Instax film and Instax products (including cameras, printers, and accessories) makes up a majority of their consumer imaging segment, whcih in 2022 had sales which were estimated to be about 266.9 billion yen with an expected increase of up to 30% in 2023. Despite the widespread use of digital cameras and smartphones for general photographic use, Fuji’s Instax business is so significant that it accounts for nearly 24% of the entire Fuji Corporation’s annual profits.

For such a dominant product, you might think that learning the history of Fuji’s early entry into the business would be easy to discover, yet very little of this early history is documented in English with most information contained within Japanese language magazines and other press material. While researching this article, I found a spattering of source material in defunct Japanese websites at web.archive.org and one article from the October 1987 issue of Asahi Camera generously scanned and translated by site reader Jesse Wisdom.

Fuji’s entry into Instant Film began in 1981 when Fuji president Minoru Ohnishi announced a new instant photo system called Fotorama. An article published in the October 12, 1981 edition of Nihon Keizai Shimbun, Japan’s national newspaper claimed that the new system would challenge two US monopolies in the instant film world. Although not mentioned by name, it was obvious the two companies were Polaroid and Kodak. The need to expand into this new market came out of a need to reverse a slowing of sales in Fuji’s traditional markets. A visionary leader who during the 1960s and 70s studied the US photo market and its economy, Ohnishi was appointed president with the task of reversing Fuji Japan’s slowing domestic growth.

In the weeks that followed, Ohnishi would lead a presentation of Fuji’s new Fotorama system for 10 dealers across the country in Tokyo. The first products would go on sale on October 24th, consisting of two cameras, the Fotorama F-10 and F-50s, one type of ASA 160 color instant film called FI-10, and a compatible flash strobe.

At the time of Fuji’s entry into the instant film world, Kodak had already been producing their own instant film which would later be found to violate Polaroid’s international patents. Kodak’s design for instant film was quite a bit different than Polaroid’s at the time, and produced images that were 91mm x 69mm wide. Fuji’s Fotorama film was very similar to Kodak’s producing images of the same exact size and similar self-contained cartridges, but used a different emulsion with a slightly different speed. Despite these differences, Fuji’s film could be used in Kodak instant film cameras, allowing those with Kodak cameras to buy and use Fuji film.

Polaroid would eventually file and in January 1986 win a lawsuit against Kodak for violating its international patents, which resulted in the complete discontinuation of all Kodak instant cameras and film. Although Polaroid would at first take aim at Fuji for the same patent infringement as Kodak, Polaroid didn’t see Fuji as a competitor in the US, and would settle on an agreement between the two companies to share technologies, thus allowing Fuji to continue making instant film and cameras long after Kodak was forced out of the market.

When it was first released, sales of Fuji’s Fotorama system in Japan far exceeded expectations. This resulted in almost immediate production backlogs which slowed the release of Fotorama in export markets. In early 1982, the first exported products were sent to Indonesia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan in Asia and then in early 1983 into South Korea, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Beyond that, products would be exported to other Africa and South American countries, but not North America where Fuji had no intention of going head to head with Polaroid or Kodak.

Fuji’s lineup of cameras and film stocks expanded with models adding support for auto focus, build in flashes, and even cameras that could talk to you with “reminders” to “wrap the film cover” or “clear the film” similar to Minolta’s Talker 35mm camera.

After Polaroid’s successful lawsuit against Kodak in 1986 and Fuji’s subsequent technology sharing agreement, the company was allowed to begin exports of its products to North America. Around this same time, Fuji released a new 800 speed version of their Fotorama film that was no longer compatible with Kodak instant cameras as the cassettes were physically different but also that none of Kodak’s cameras had the ability to meter for 800 speed film. While this wasn’t explicitly said anywhere that I could find, I see this as further evidence of Fuji wanting to play nice with Polaroid. Beyond the Fotorama 800 speed film, further advancement of the film would be released in the 1990s as Fuji Ace Instant Film.

With a successful instant film system, in early 1987, Fuji would expand its product offerings to include peel apart instant packfilm, a style of instant film used largely by professionals as the images were quite large at 108mm wide and 85mm tall. Fuji would release two types, a color film called FP-100 and a black and white version called FP-3000B Super. Both films directly competed with Polaroid’s 660-series pack film, but would stay clear of Polaroid’s patents as they had expired.

Although Fuji’s new film was intended to be used in one of many packfilm Polaroid Land Cameras, the company would also release a camera of their own, which they conveniently called the Fujifilm FP-1 Professional. This new camera was designed specifically for Fuji’s new packfilm, and was a bellows type camera with a large coupled rangefinder, a 10-speed leaf shutter, and a 5-element 105mm f/5.6 Fujinon coated lens.

The FP-1 Professional would only be available in Japan and would go on sale June 25, 1987 for a price of 69,800 yen. The camera, despite being branded “Professional” was a pretty simple camera with no metering or electronics of any kind. Beyond the large and bright coupled rangefinder, the camera was quite retro, requiring manual exposure and manual focus. According to the article in Asahi Camera, this was done intentionally to keep the cost of the camera low, as adding any type of automation would have likely resulted in a camera costing 100,000 yen or more.

In comparison tests of Fuji’s new FP-100 and FP-3000B Super films shot in the FP-1 Professional camera compared to those shot on Polaroid’s own pack films, sharpness and clarity of the black and white FP-3000B Super was said to be identical to Polaroids and the FP-100 showing superior sharpness and more vibrant colors than the comparable Polaroid film.

We know that the FP-1 Professional camera was not exported to the United States, but it is not clear whether the film it used was. My best guess is that exports of the film came much later, likely in the 1990s when Polaroid Ace film and cameras started to be sold here. As I scoured late 1980s and 1990s photographic magazines, I found no mention of it until a February 1992 ad for Adorama selling a single 10-sheet pack of FP-100 for $15.49. This price, when adjusted for inflation compares to just under $35 today.

Fuji would eventually expand their peel apart film offerings to include other types of film such as a 100 and 400 speed black and white film, and in 2002 would revise the original FP-100 film and release an updated version called FP-100C which came in a less expensive all plastic cassette, but also offered more accurate colors and better archival life. A version of FP-100C called 100C Silk was also released which produced more muted colors and came with a textured finish which was less likely to show fingerprints compared to the glossy finish of other films. In addition to these new films, Fuji would also release a larger 4×5 size and a dedicated 4×5 back for large format sheet film cameras.

With the release of FP-100C in 2002, Fuji announced that they officially make available packfilm in the North American market, which suggests that earlier stocks sold in the US were imported through dealers not through Fuji directly.

With the release of in Instax in 1998, by the first decade of the 21st century, Fuji would have at least three different lineups of instant film available, the original 800 and Ace series integral films, the FP-series peel apart film, and the new compact Instax film. Fuji and Polaroid would happily co-exist in the market until 2008 when Polaroid would announce that the company was discontinuing all of its products and going out of business. With support from a much larger corporate family with a very diverse portfolio, Fuji wasn’t susceptible to the same financial woes as Polaroid and would continue offering both Instax and peel apart film (the 800 and Ace films were discontinued in 2010). Anticipating a shortage of supply due to Polaroid’s exit from the market, in 2009 Fuji would increase production to meet demand.

In the 2010s, sales of Fuji Instax film would remain healthy, posting year over year improvements in sales, but the market for peel apart film was trying up. With Instax catering to children and teenagers who saw instant film as a novelty, peel apart film was marketed towards serious photographers who by that time had all but give up on film. Sales continued to decline, and by February 2016, Fuji had announced that production of the two remaining types, FP-100C and FP-3000B would end.

After Fuji’s discontinuation of peel apart film, no manufacturer in the world made film that supported the huge number of cameras build for it like the FP-1 Professional. Unused left over stock began to flood used marketplaces like eBay at hugely inflated prices. If the film is refrigerated or stored in a cool temperature controlled location, Fuji’s film can survive upwards of 10 years beyond its expiration date, so with the final stocks produced having expiration dates in early 2018, that suggest there may still be viable ways to use this film until 2028. As I write this article in November 2023, some refrigerated packs of Fuji FP-100C and FP-3000B can be bought on eBay for over $180 each!

Today, cameras like the Fuji FP-1 Professional are rare to find. That they were only sold in small numbers on Japan and that the film they use is no longer made makes them a challenge to find. Even if you do manage to find one in good condition for sale, to spend a large amount of money on something that can’t easily be used makes for a questionable economic decision.

Fortunately, for readers of this site, supplies of Fuji peel apart film that has been refrigerated since new occasionally pop up and can be shared online. There aren’t too many people out there both with this camera or the film it needs, so what follows may be one of the last ever user reviews of the camera and the film. If you are motivated to buy and use one yourselves, I encourage you to act fast, and open your wallets wide as the window to shoot one is narrowing every single day!

My Thoughts

One of the greatest things about collecting and using old cameras is how many of them still work today. When a camera is inoperable, in most cases, they’re just in need of a cleaning or shutter service. To help every camera in need of a service find someone who is willing and capable of a service, I put together a Worldwide Camera Repair Directory which I’ve done my best to vet as many of the specialists out there.

Sometimes though, a perfectly working camera might not be usable because the film it was made for, no longer exists. If the film is something like Kodak Disc film or the Advanced Photo System from the late 1990s, there are no current makers of fresh film. While some clever hacks have been made to adapt modern films to these extinct film formats, they often are difficult to do, and produce lackluster results.

In the realm of instant film however, options for modern stocks range from less than ideal to downright unavailable. Somewhere between those two options is peel apart instant film. Polaroid made a large number of options with their 660 series pack films, but discontinued those stocks in 2009, leaving Fuji as the only maker with their FP-100C and FP-3000 films, but in 2016, they too discontinued their film, leaving no fresh film stocks available.

Since then, prices on expired peel apart film have escalated to ridiculous heights, with some selling for over $100 for a single pack of film. As demand exceeds available supplies, for most people, myself included, shooting cameras designed for this film seemed like a thing of the past.

In July 2023, I was fortunate enough to come across a stash of refrigerated FP-100C, FP-100C Silk, and FP-3000 film stocks and I wanted to find a camera that could use the film to test it out. The most commonly available options are the wide range of Polaroid Land Cameras made in the 1960s and 70s which use the film. In an earlier attempt for shooting this film, I loaded up a Polaroid Land Camera 250 to test, but unhappy with those results, and learning of the Fuji FP-1 Professional, I knew I needed to get one.

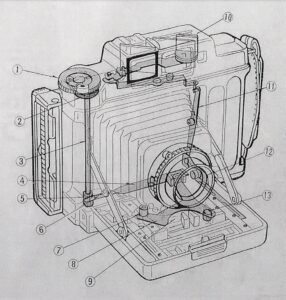

The Fuji FP-1 Professional is an interesting camera that is basically an old school folding bellows camera, except instead of shooting some type of roll film, it uses instant pack film. The camera has an almost entirely plastic body with some metal bits, a folding bed with bellows, leaf shutter with speeds from 1 to 1/500 and a Fujinon lens. The camera is entirely mechanical with no electronics or automation of any kind. The only feature that is even remotely “Professional” is the coupled rangefinder with thumbwheel focus.

The camera is quite large, much bigger than any 120 roll film camera and even some 116 folding cameras. Despite a large amount of plastic, the camera is quite heavy too, weighing 1326 grams (2.9 lbs) which when combined with its large large size, makes the camera quite cumbersome to hold.

Up top, other than the name of the camera, you’ll see an accessory shoe in the center which has a plastic circle that looks like it might have been intended to have a hot shoe, but was removed at the last minute. The camera does have a standard PC flash sync port on the side of the shutter, so with a clip on flash gun, the FP-1 could shoot flash exposures. In the far right front of the top plate is the cable threaded shutter release. Its location is comfortably located with your right hand wrapped around the side of the body.

The base of the camera has a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket and the camera’s serial number. The inclusion of a metal tripod bushing is a nice addition considering the camera’s large size and support for Bulb exposures although the lack of a self-timer seems like a curious omission.

The left side of the camera has a build in hand strap, which comfortably wraps around your left hand which when combined with a rather large hand grip that extends to the front of the camera, makes carrying the FP-1 quite comfortable. Despite a heavy weight, you could walk around with this camera attached to your hand for quite a long time with minimal discomfort. Hopefully you like hand straps because the camera lacks any sort of strap lugs, making the use of a neck strap difficult. The camera’s right side has the opening for exposed images, but more on that later.

Around back, there’s little to see. Near the top is a circular eyepiece for the viewfinder and a large thumbwheel for controlling focus. Like some earlier Fujica cameras such as the Fujicarex II and Voigtländer Vitessa, the FP-1 is focused by rotating this large wheel with your thumb. This allows for quick and easy one handed focus, without having to relocate your hand to the front of the camera when focusing. Beyond the eyepiece and thumbwheel, the rest of the back is a large sea of black plastic.

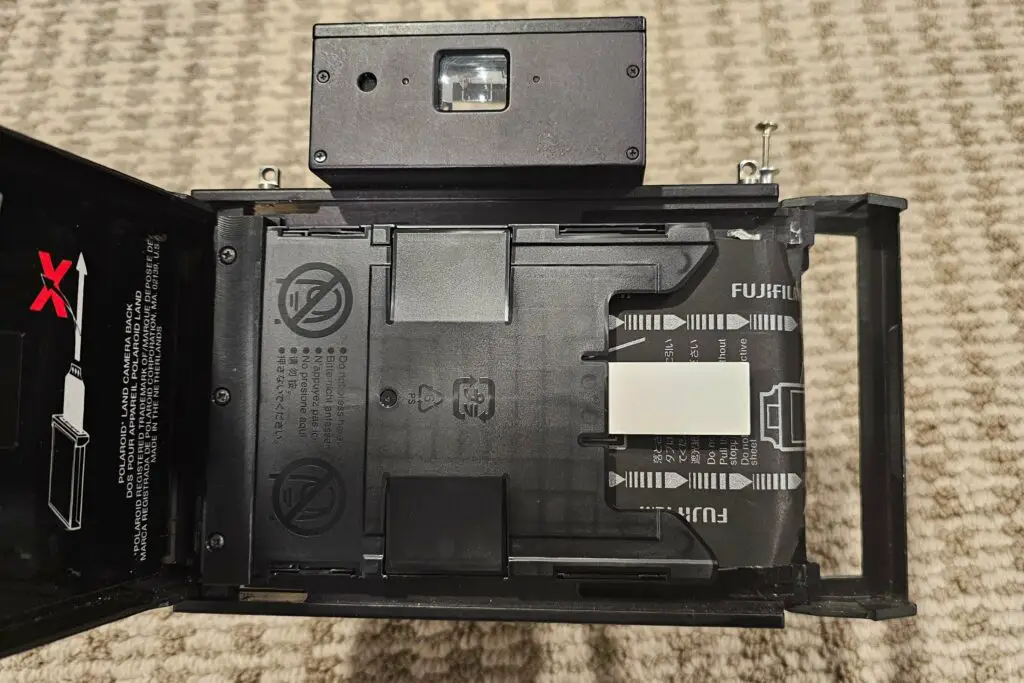

Loading film is a bit more involved than other types of instant film, but isn’t difficult. I’ll cover the process in greater detail below, but the short explanation is to simply open the door by first releasing the hinged lock on the right, and with the door open, insert a new film pack with the paper dark slide facing forward. Each pack of instant film has a bunch of paper tabs sticking out of one side. Make sure that before closing the door, none of the paper tabs will be obstructed by the door. With the door shut, fold over the lock to secure it, and completely remove the paper dark slide from the camera to ready the pack for the first exposure.

Looking down upon the shutter, you see the exposure controls for the Fuji leaf shutter. A lever closest to the body smoothly controls the diaphragm with f/stops from f/5.6 to f/64. A large chrome ring around the perimeter of the shutter controls shutter speeds from 1 to 1/500 seconds plus Bulb. The shutter speed control has strong click stops, reducing any chance of accidental speed changes. Since the camera has no traditional film transport, there is no coupling for cocking the shutter. Since film doesn’t transport through the camera, you must first cock the shutter before each new exposure using a lever near the top of the shutter. The FP-1 lacks any sort of double image prevention, so if you wanted to double or triple expose the same piece of film, it is very easy to do.

When opening the camera, the folding mechanism is not self-erecting, which means opening the door and extending the lens is done in two separate steps. Beneath the shutter are two gray plastic grips which when squeezed together allow you to manually push in and pull out the shutter and bellows to get it into shooting position. Also on the inside of the bed is a focus distance scale which is coupled to the thumbwheel on the back of the camera, showing distances from 0.8 meters to Infinity.

The viewfinder is very large and bright, showing projected frame lines with manual parallax correction marks, plus a circular rangefinder patch in the middle. The main part of the viewfinder has a bluish tint with the frame lines and rangefinder patch in frosted white, giving excellent contrast. Although I wouldn’t describe the rangefinder patch as small, considering the huge size of the camera and overall large opening for the viewfinder, I feel as though the camera could have benefitted from a larger rangefinder patch, as there’s clearly enough room for one. I found focusing the FP-1 quite easy in low light. This being an unmetered and fully mechanical camera, there is no other information visible in the viewfinder such as selected shutter speeds or any exposure information.

The Fuji FP-1 Professional made its debut around the time Fuji started making peel apart film. Prior to FP-100’s release, Fuji’s Fotorama film was designed to work in the company’s own or Kodak’s instant film cameras, but with the FP-1, an older, but more popular style of film was used that produced better results. The new film would have been compatible with a large number of Polaroid Land Cameras dating back to the 1960s, but with the FP-1 Professional, now Fuji had something to sell you.

That I have Fuji’s first peel apart instant film camera as my test bed for some of the last peel apart film in existence is very ironic in an “alpha and omega” sorta way, but I could not think of a better way to review not only a rare and uncommon camera, but also a film from an era that’s already gone.

Loading and Shooting Film

Loading peel apart film like Fuji FP-100C is unlike any other film out there. The most common type of instant film, Polaroid 600 and SX-70 is as simple as sliding a cartridge into a lot and the camera does everything for you. With peel apart film, the process is still very easy, but there are a few extra steps which I’ll go over.

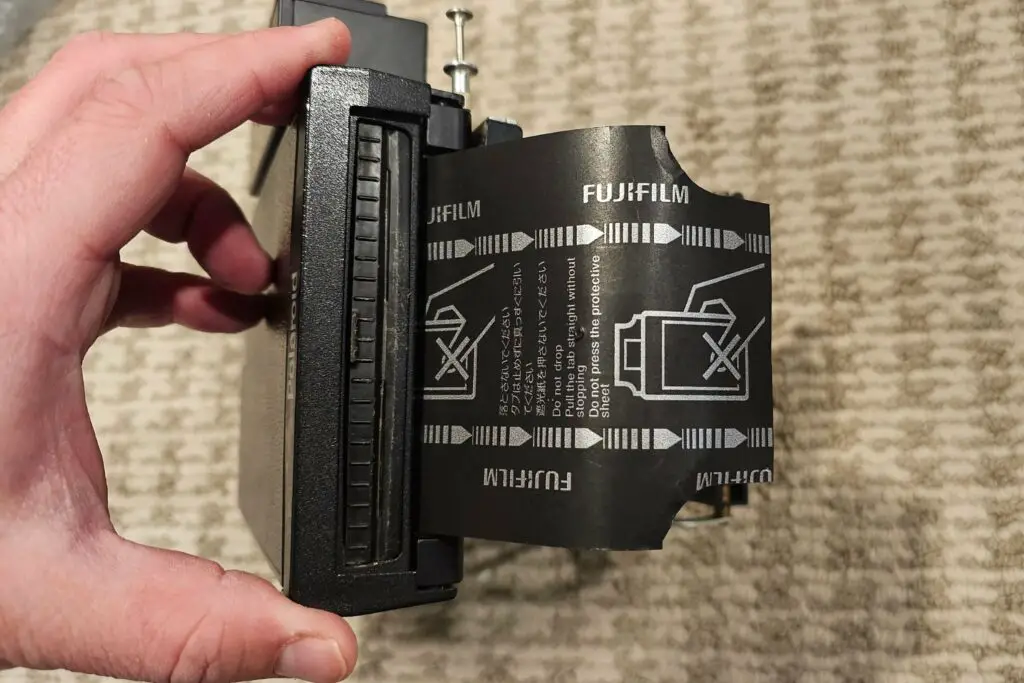

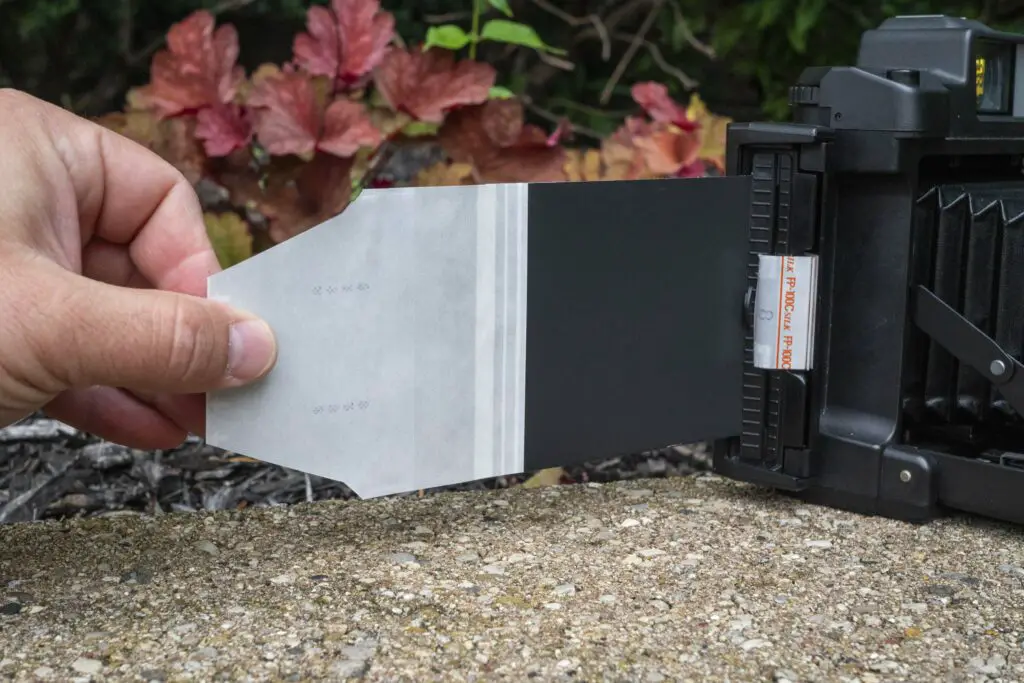

Note: The images below show a different camera from the Fuji FP-1, but the process is exactly the same.

All peel apart instant film comes sealed in a light tight foil wrapper to protect the film. You should leave the film in the wrapper until the last possible moment when it is time to load the camera. Although there is a dark slide to protect the light sensitive film, you should minimize how long the cassette is exposed to light.

Open the film compartment by swiveling the latch on the right outward and then swinging the left hinged door open. If there is an empty cassette still in the camera, lift it out and discard it. With the film door open and the new cartridge out of the foil wrapper, slide it into the film compartment with the paper dark slide facing the lens. Each cassette has a rectangular foam pad on the right side which should look similar to the images above.

Each new cassette will have a black paper leader that sticks out through the side of the cassette. This paper leader must pass through the opening on the door latch and must not be obstructed. Pay attention when closing the door and make sure this paper leader is not pinched or folder under something before closing the latch.

With the latch closed, securely grip the black leader with your fingers and give it a steady but firm tug and pull it completely out of the cassette. The paper leader is slightly over 12 inches long, so keep pulling on it until it is completely out of the camera. Once this black paper is removed, the film cassette inside the camera is no longer protected from light so do not open the camera until you have finished the cassette.

Assuming you did this correctly, another set of white paper leaders will stick out of the same area that the black leader was. There will be a total of ten of these white paper leaders as they are attached to each of the ten exposures of film. The cassette is designed in a way that after each exposure is removed from the camera, the next paper leader will automatically stick out of the camera. Each of the paper leaders are numbered 1 through 10 so you know how many exposures are left.

Once the first paper leader is sticking out of the camera, it is ready to shoot. Perform the steps needed to set exposure, cock the shutter, focus the lens, and then make the exposure. Once you’ve fired the shutter, the image has been captured on the film, but development does not being until you remove it from the camera. If you make a photo and leave it in the camera, you should not count that time towards development time.

To develop the photo, you must physically remove it from the camera. Do this by gripping the white paper leader, and like the black leader you removed earlier, give it a firm and steady tug until the film exposure is removed from the camera. It is important to pull the film out with even speed and try not to stop pulling with the exposure half out as it may cause an uneven spread of the development chemicals.

The time in which the film needs to be develop varies by the type of film and the outside temperature. When shooting instant film in colder weather, it takes longer for the exposure to be made. Generally speaking, it is best to wait a minute after pulling the exposure from the camera, before peeling it away from the backing paper.

Even after removing your exposed photograph from the backing paper, the image will still develop in normal light. Color film has a tendency to have a brownish tint with lighter colors immediately after being exposed. Assuming a proper exposure is made, the colors should correct within another minute after separating from the backing paper. If after several minutes, you are not happy with the look of your photograph, then you should try to redo the photo with different exposure settings.

My Results

I was fortunate when first acquiring the FP-1 to have a variety of film to test. With it, I received multiple packs of color FP-100C and FP-100C Silk and the black and white FP-3000B. Most of the film was stored in a fridge, but not all, and of the stuff that was in the fridge, I can only say that the person I got it from had it in a fridge, but I do not know the history of it before then. Based on the experiences from other people, this style of film seems to have a shelf life of up to 10 years after the expiration date if kept cold, but that can change dramatically as conditions vary. Nevertheless, I loaded up some packs and took with me the FP-1 on various family trips and while walking around the house.

I can split up my lifetime experience with instant film into two distinct eras. The first, was when I was younger and nearly every suburban family had some form of Polaroid instant camera. These models were usually consumer grade models from the 600 series, and produced the square prints that most people my age associated with instant film. Maybe some of my friends whose parents had more money went with a higher end Spectra camera, or possibly even Kodak pack film camera, but for the most part, these early instant photos were popular due to their convenience, not necessarily image quality. People back then didn’t care about color accuracy, or sharpness in their photos.

The second era in which I’ve experienced instant film has been with newer Impossible (now Polaroid Originals) film which is a “reformulation” of classic Polaroid film, but made by an entirely new company. While the effort that has gone into the new film to reverse engineer a very proprietary and complicated film is commendable, the results from the film…well, they suck. Improvements have been made since the earliest Impossible branded films, and the black and white film is okay, the color film is soft, with muted colors, and very low contrast. For the price it costs for a single 8 exposure pack (original Polaroid film used to give 10 exposures), I just don’t think the results are worth it.

Having never shot any peel apart film either made by Fuji or Polaroid, after hearing glowing reviews of the film, I was eager to give it a try. Equipped with one of the more capable peel apart film cameras ever made and a supply of film, I took it out shooting eagerly awaiting some results.

My initial reaction to seeing the first images were that this was, without a doubt, better than anything I had seen from Polaroid Originals. I lack the understanding of exactly how instant film is made, but it seems very complicated, and it is clear that Fuji was doing something that the new company isn’t able to. I noticed that colors were much more accurate, capable of vibrant blues and reds, while still showing good shadow detail. I did notice that my images were still a bit soft, at least compared to that of a similarly sized film negative or even a 35mm negative. It was still better than anything I got during my test of the Polaroid SX-70 however.

An additional benefit over images shot on the SX-70 and lesser instant cameras was the quality of the 5-element Fujinon lens. While some Polaroid cameras did come with high spec Tomioka lenses, and there was no shortage of high quality 4×5 cameras which could shoot instant film, most instant film cameras have simple lenses with questionable optical quality. I noticed that in brightly lit scenes where I stopped down the f/5.6 lens to f/11 or smaller, sharpness was excellent across the frame, but the images were definitely soft wide open. Images shot indoors or in poor lighting were universally soft across the frame, and I also noted that I missed sharp focus often suggesting some combination of the rangefinder not being in alignment and that the Fujinon lens has a very narrow depth of field wide open.

I got generally good results from the Fuji FP-100C and found the film to work best in bright sunlight. The FP-100C was similar, but I noted a warmer color pallette with enhanced browns, oranges, and yellows. Without a doubt, the biggest change with the Silk film is in the matte coating on the photos. Where the regular FP-100C was very glossy and easily showed fingerprints, I found the Silk film to have a very prominent texture, similar to the textures used on many photo paper from the mid to late 20th century. Sadly, all of my attempts shooting the black and white FP-3000C were poor, with noticeable degradation of the film and extremely washed out contrast.

I hesitate to go much further describing my results as I don’t want this to turn into a film review as I want to mostly talk about the Fuji FP-1, but I can positively say that the images you get from Fuji’s peel apart film are leaps and bounds better than anything currently still in production.

As for the camera itself, I found that the shooting experience of the FP-1 was mostly good with a few cons. For starters, the camera is very large and awkward to hold. I was happy with the large hand grip, which helped to retain a firm grip on the handle while walking around, but I felt that because of the camera’s large size and fragile bellows, this would be a difficult camera to carry around all day on a hike or family trip to the zoo where you might want to capture fun candid photos.

When it was time to shoot, the large and bright viewfinder was a joy. The rangefinder patch was large and easy to use, working like any rangefinder I’ve used on any number of 35mm and roll film cameras. I very much appreciated the location of the rear thumbwheel focus which allowed for each focus changes with the camera to your eye. Fuji employed a similar backwheel focus on earlier 35mm rangefinders and even their first SLR, the Fujicarex II, but it made the most sense here.

Having to cock the shutter before each exposure took a little getting used to when considering this camera was made in the 1980s, many decades after self cocking shutters had become the norm, but that this camera lacks any sort of film transport which would require a lever to cock the shutter, I was forgiving of having to do this before each shot. In fact, I found that having to remember to cock the shutter before each shot was a good way of not accidentally exposing any images. If you have recently paid the asking prices for some of this film in 2023, you will definitely appreciate not wasting any exposures.

A curious omission to the FP-1 that I wish it had was a self-timer. Instant film is very popular at social gatherings, and there are many instances where the photographer might want to include themselves in the image and the lack of any ability to fire the shutter with a delay seems like a curious omission, especially considering countless leaf shutters were manufactured on folding camera for decades before the FP-1 was built. While I understand Fuji’s desire to keep the costs of the camera low, a self-timer seems like it would have been an inexpensive, yet useful feature to add.

The Fuji FP-1 is a very basic folding camera from an era not known for folding cameras. If it shot regular negative or positive film, this review would be easy to write as I’d say it was a rudimentary, but refreshing nod to the past. A mechanical anachronism in an increasing modern and electronic era. But its use of peel apart film throws a wrench into my final opinion of it. On one hand, yes, it is considerably more capable than the hordes of basic Polaroid Land Cameras that used Polaroids peel apart film. The large and bright coupled rangefinder and back focus wheel make focusing a snap, and the 5-element Fujinon lens makes sharp and nicely detailed images when stopped down.

That this is one of the best (and only) ways I’ve been able to experience peel apart film is its biggest compliment. The 900 pound gorilla in the room of course, is the film itself. Fuji discontinued this film in 2016, and the last runs of film expired in 2018. Even with a best case 10 year shelf life, this film is already more than halfway past its usability date and as each day passes, less and less of this film is available to shoot.

If you REALLY want to experience peel apart instant film, your best bet is to get a time machine and go back in time. Assuming you’re all out of Deloreans or phone booths, go ahead and open your wallet wide and look for some film. If you happen to find some, then maybe consider picking up an FP-1. This might be the best way you’ll ever get to experience a type of film that likely will never be made again.

If however, you just casually are interested in this style of film (and still don’t have a time machine), I definitely encourage you to live vicariously through me or other people who have written about it as the cost of even a single pack of film has reached ludicrous heights. That, combined with the high prices of the better cameras that can use it like the FP-1 make for a very impractical photographic solution. I’ve never tried Instax Wide, but that seems like a much more economically viable alternative.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Fuji_FP-1

http://moominsean.blogspot.com/2012/03/its-fuji-fotorama-fp-1-style.html

https://www.filmwasters.com/forum/index.php?topic=773.0

https://bluemooncamera.com/museum/exhibit/12/fuji-fp1

https://www.reddit.com/r/Polaroid/comments/xwgj2i/fuji_fotorama_fp1_professional/

I’ll always regret not trying this film when I had the chance — but not enough to warrant getting both the film and a camera now — so I do appreciate this review (and many, many of your past ones as well) very much. Thanks, Mike, for allowing me to live vicariously through you.