This is a Royal 35-M, a 35mm rangefinder camera produced by Daiou Shashin Kōgaku in Tokyo, Japan starting in 1957. The Royal 35-M was one of six models made under the Royal name, and many others rebadged for sale with brand names such as Wirgin, Hanimex, Brumberger, Luxall, and others. The Royal 35-M was a typical late 1950s Japanese rangefinder equipped with a large and bright viewfinder, uncoupled selenium exposure meter, and fixed f/1.9 lens made by Tomioka. Although the Royal 35-M has a fairly common design and list of specifications, it was a well built camera with an excellent lens that could make high quality images.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/1.9 Tomioka Tominar coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 2.6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Copal MXV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate display

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 662 grams

Manual: https://cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/royal_35-m.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Royal 35-M is a high quality fixed lens 35mm rangefinder camera made by a company that was known for making good cameras, but didn’t survive the 1950s, and is relatively unknown today. Featuring a good lens and easy operation, the Royal 35-M makes great images, but struggles to differentiate itself from a huge number of very similar fixed lens 35mm rangefinders. If you can find one of these cameras in good shape, it is worth picking up, but if you’re looking for something different or unique, you may want to pass. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

As the Japanese camera market exploded in the early to mid 1950s, what started out as a cottage industry consisting of a variety of factories who previously produced optical goods for the Japanese military, into a thriving market with over several dozen manufacturers. While the histories of the most successful brands are well known, there exist a huge number of very small Japanese camera makers whose stories are largely untold. Many of these companies only produced cameras for a very short period of time, some even consisting of a single model. In fact, many companies who produced cameras in Japan at this time, weren’t even camera companies, rather they were in some other industry and for unknown reasons, decided to dip their toes into camera making.

As the Japanese camera market exploded in the early to mid 1950s, what started out as a cottage industry consisting of a variety of factories who previously produced optical goods for the Japanese military, into a thriving market with over several dozen manufacturers. While the histories of the most successful brands are well known, there exist a huge number of very small Japanese camera makers whose stories are largely untold. Many of these companies only produced cameras for a very short period of time, some even consisting of a single model. In fact, many companies who produced cameras in Japan at this time, weren’t even camera companies, rather they were in some other industry and for unknown reasons, decided to dip their toes into camera making.

For most of the Japanese camera makers who only existed for a very short time, the reasons for their disappearance are varied, and beyond the scope of this article. For many however, the companies that were successful succeeded because they had distribution. In my time researching Japanese camera makers, the most common reason a company failed was poor distribution. If you couldn’t your cameras into the hands of people willing to pay for them, you failed. This happened time and time again to smaller companies, and even some larger ones like Miranda and Aires.

This review is for one of the lesser known companies called Daiou Shashin Kōgaku who like many small Japanese camera makers started out as a small distributor in Tokyo. While I found very little information about the company online, I feel safe in assuming that they were similar to dozens of other Japanese distributors who sold photographic goods, both produced in Japan and imported from elsewhere, along with probably a large number of non-photographic goods in and around Tokyo, Japan.

There is very little info about Daiou Shashin Kōgaku online, but the usual sources claim the same sentence or two of facts over and over which is that the company produced cameras from between 1955 and 1959 and sold a number of similar fixed lens 35mm rangefinders with lenses ranging from f/1.9 to f/3.5, under a variety of names including under their own Royal Camera Company name, Wirgin, Brumberger, Hanimex, and a couple others. All of the Royal cameras have a design that loosely resembles the Contax or Nikon rangefinders, but should not be considered a copy as beyond a passing resemblance, the cameras are very different. In addition, all Royal cameras had fixed lenses, except for a very small number of Royal 35S models which had a proprietary screw mount, but is thought to be a prototype with a very low number ever produced.

While I have no reason to doubt this information, I believe there’s more to the story as Daiou Shashin had quite a few connections in the photography world. Securing distribution from so many different companies all over the world is not an easy thing to do. The company’s cameras sold everywhere, including the United States where it usually appeared using the Wirgin name, but sometimes also the Royal name.

Below is a gallery showing a sampling of various different cameras made by the Royal Camera Company. All images courtesy of Colin Clarke, flickr.

The most comprehensive list of Royal cameras courtesy of collector Colin Clarke includes the following models:

- Royal 35, 35S, 35M, 35LE, 35P, and Royal Mark S-2

- Hanimex C-35, D-35, and Holiday

- Mansfield Skylark E and V

- Brumberger 35

- Luxall 35

- Hiyoca

- Wirgin 19E

- Unicorn 35

- Torca

- Ogikon 35P

Of the models listed above, it is not clear which models were sold where. Hanimex was a brand often found in Australia and the Brumberger, Mansfield, and Wirgin models were known to be sold in the United States, but it is likely these cameras were sold in a variety of other locations such as Europe and elsewhere.

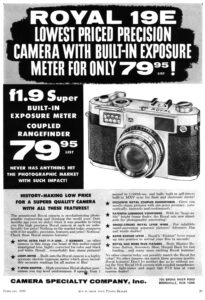

In the United States, the ad to the right appeared in the February 1959 issue of Modern Photographer for US based distributor Camera Specialty Company for a model called the Royal 19E which appears to be the Wirgin 19E with the original Royal name, suggesting that some variability between the different names also occurred. The Royal 19E carried a retail price of $79.95, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to around $850 today.

Exactly when the Royal Camera Company stopped producing cameras or what ultimately happened to the company is unknown. It does not appear that any portion of the company was merged into or otherwise absorbed by other companies.

One theory is that since many Royal cameras came with Tomioka lenses, and Tomioka had a relationship with Yashima/Yashica, and the Yashica 35 rangefinder shares more than a passing resemblance to some of the Royal models, that perhaps some of the company merged with Yashica, but that is just an unsubstantiated guess.

A more plausible explanation for why the Royal Camera Company disappeared was that in 1959, around the same time Royal cameras stopped being made, an organization called the Japan Machinery Design Center was created as a division of the Japan Camera Inspection Institute.

You’re probably familiar with those oval gold foil JCII stickers that appeared on many Japanese cameras and lenses from the 1950s through the 1980s. The JCII was created in 1954 to improve the quality of Japanese optical goods as a way of ensuring to the world that Japanese products were of the highest standard. Although some Japanese companies like Nippon Kogaku and Canon had high standards before the JCII, quality control was wildly inconsistent prior to that, and the Japanese government thought that cheap Japanese products were holding back the success of higher end products, so the JCII was created as a guarantee that any product with its sticker was a quality product.

While the JCII only acted as a governing body for quality control, the JMDC was created to throttle the widespread practice of so many different companies making so many similar designs. A huge number of Japanese companies were producing nearly the same styles of cameras. If you look at how many different similar fixed lens 35mm rangefinders, and 6×6 Twin Lens Reflex cameras were being made in the 1950s, you can see why the Japanese government wanted to end this practice as so many nearly identical models were confusing to the public and diluting the market.

It is my own personal opinion that pressure from organizations like the JCII and JDMC had an effect on Royal, the third, and most likely explanation was that the company ceased to exist, like a huge number of Japanese optics companies in the late 1950s, due to an overwhelming amount of competition. By 1960, the Japanese optics industry was in full swing, led by industry leaders like Nippon Kogaku, Canon, Chiyoda Kogaku, Konishiroku, and several others. With so many A and B-list camera makers out there, smaller companies like Royal just couldn’t compete and simply went out of business.

Today, Japanese cameras from the 1950s are generally pretty collectible. That models credited to the Royal Camera Company are part of this group says that people generally like adding these to their collection. While I’ve only ever found one collector who specializes in this one brand, I am quite sure that many collectors have at least a couple. and for good reason, they are attractive and reasonably well built cameras that usually came with good lenses. Royal cameras likely will never be the crown jewel (no pun intended) of anyone’s collection, but when found for a reasonable price, make an excellent addition.

My Thoughts

A long time ago, when I first started collecting cameras, the entire landscape of film camera history was foreign to me. In those early days, I could name a handful of the most popular models by the most popular makers. Nikon, Canon, Minolta, maybe a Pentax, but that’s about it. Whenever I would come across strange marques such as Braun, Nicca, or Clarus, they were about as foreign to me as a Nikon F3 is to my 6 year old daughter.

One day while browsing one of the camera collector groups on Facebook, I saw a post by a guy named Colin Clarke who for some reason, had a fondness for a very specific type of camera, 35mm fixed lens rangefinders by the Royal Camera Company, or in Japanese, Daiou Shashin Kōgaku. The particular camera that Colin was a fan of was the Royal 35, which itself had a huge number of variations, sub models, and name variants. Models with names like Brumberger, Luxall, Wirgin and Hanimex were all based off this one model and for one reason, Colin Clarke was drawn to it. I remembered thinking that I wanted one of my own, but lacking the knowledge, dedication, and financial resources to acquire one, I moved on and thought that maybe one day one would come my way.

It would turn out that day would come in 2020, during the early days of the COVID pandemic where house bound collectors like me spent all their free time on eBay looking for things to buy. As it would turn out, a nice looking Royal 35-M would go unnoticed by Colin and anyone else interested in these cameras and I was able to pick it up for a song.

If you’re thinking “Gee Mike, it is 2023, if you bought this in 2020, what have you been doing with it?”, well the answer is, I kinda forgot about it. Turns out I did such a good job of forgetting about this camera when I first learned of it, that I forgot about it again when I finally had one. In my defense though, my collection was WAAAAY bigger in 2020 than when I first started, and I am sure that right now, as I write this, I have cameras in a box somewhere in my house that I’ve forgotten about too.

But back to the Royal. With a body very loosely resembling a Contax or Nikon rangefinder, except with a leaf shutter and fixed lens, the Royal 35-M is an attractive camera with what should be a good lens. The build quality seems to be on par with at least a dozen of other Japanese fixed lens leaf shutter rangefinders from the mid to late 1950s, no better, no worse. The weight, viewfinder, lens formula, and ergonomics all fit into a crowded grouping of cameras that were churned out by the tens, possibly even hundreds of thousands back then.

Up top, the Royal 35-M has a pretty typical control layout. On the left is the rewind knob with fold out handle. Next is an accessory shoe with two small features above and to the right which are easy to miss. The first is a small electrical contact which the manual calls the “meter amplifier joint”. This is where an accessory selenium meter can be attached to the camera’s built in Sekonic meter to increase its sensitivity in low light. This is a feature included on other higher end 35mm rangefinder cameras like those made by Aires and other companies. Next to it is a zero adjustment screw for the meter display to its right.

The meter display is uncoupled, which means that no changes to shutter speeds or lens aperture has any effect on the readout. To use the meter, set your film speed to whatever ASA setting is applicable and then by pointing the camera at something, whatever light value the needle points to will give you an appropriate combination of shutter speeds and f/stops. This is a fairly rudimentary system, but was par for the course when this camera was new, and in my opinion, better than coupled Light Value Scales found on some other cameras.

Above and to the right of the meter display is the cabled threaded shutter release button, then the film advance lever, and finally a window for the automatic resetting exposure counter. The film advance lever requires a full 180 degree swing to advance the film one full frame, and cannot be done in several smaller motions, not that you would need to. The exposure counter is additive, showing the number of exposures made on the current roll.

Flip the camera over and on the bottom is a 1/4″ tripod socket on one side and what is perhaps the largest film rewind button I’ve ever seen on a camera. The diameter of the rewind button is greater than that of the entire tripod socket. This neither helps nor hinders its operation, but is a bit unusual. On the plus side, you could easily locate the rewind button with the camera to your eye, not that you’d ever have a reason to do something like that!

Around back, there is little to see other than the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder. Nothing else is on the back of the camera, not even a serial number or the camera’s name embossed into the body covering. The body covering on this example seems to be holding up well, and doesn’t show the typical signs of peeling or cracking often seen on lesser cameras.

The camera’s right side has a sliding latch for opening the film compartment door. Both sides and forward angled metal strap lugs. The orientation of the strap lugs help prevent the camera from tipping forward while out shooting with it. This is a feature which is more useful on SLRs as they may have very heavy lenses attached to it, but the fixed lens of the Royal doesn’t really make this a requirement, but it doesn’t hurt to have, either.

Opening the left hinged film door reveals an ordinary looking film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed take up spool, held in place by a large metal clip. Simply slide the tip of the film leader under the clip and rotate the spool to make sure it is attached and you’re done. Above and below the film gate are two metal rails, on the inside of the film door is a large metal pressure plate covered in dimples, and to its left and right are rollers and a pressure clip, all of which are features to aide in film flatness as it transports through the camera. The Royal 35-M predates the use of foam light seals. There is no light seal material in either of the door channels and a large piece of velvet on the door hinge, which on my example was still in place doing its job to protect the film compartment from light leaks.

Looking down upon the top of the lens, we see the controls for the Copal MXV leaf shutter. A black focus helix is closest to the body and has distance marks from 2.6 feet to infinity engraved in white. In front of it is a small depth of field scale, the control ring for the diaphragm which has stops from f/1.9 to f/16. Closest to the front of the lens is the shutter speed ring, with click stops from 1 to 1/500 plus Bulb. The Royal 35-M uses the older arrangement of shutter speeds with settings like 1/5 and 1/100, predating the modern system.

The Royal’s viewfinder is large and bright, featuring projected frame lines and a rectangular rangefinder patch. The frame lines have manual parallax hash marks and do not automatically correct. Although the example here has a bit of haze in the viewfinder, contrast is still good enough to be usable in less than ideal light. There is no other information about exposure visible within the viewfinder.

Up front, the selenium light meter has a door that swivels up for low light exposures. With the door shut, a narrow slit allows some light to pass through for bright conditions. Depending on whether the door is open or shut, you use the H or L indicator on the exposure readout knob on the top plate.

Two other things seen on the front of the camera are the flash sync port in the upper right corner, to the right of the main viewfinder, and a red tipped self timer lever near the bottom of the shutter.

For someone new to 1950s Japanese rangefinders, the controls of the Royal 35-M might seem foreign compared to newer cameras, but for anyone whose shot cameras of this vintage, the Royal follows established norms for ergonomics, which isn’t a bad thing. Of course, the location of the controls don’t mean anything if the camera can’t make good images, so does it? Keep reading…

My Results

Back when I first started seriously shooting film, I decided to try my hand at being economical and bought a 100 foot bulk roll of Arista.Edu 100 film. I got a bulk loader and started loading my own cassettes. This worked okay for the first few rolls, except I failed to develop an easy to follow routine for how I would load everything in complete darkness without ruining the film. I was good at protecting the cassettes, but not the bulk roll itself, and one night, while loading in a few rolls, I finished up, and turned the lights back on, before I realized I had put the film away (I didn’t have a bulk loader at the time). Dismayed that I had just ruined 80+ feet of film I put the Arista.Edu back in a can and on a shelf to decide its fate at a later time.

As it would turn it, that day would not come for 4 years, when one night I was surveying my supplies of film and I came across that light exposed roll of Arista.Edu. Figuring that the outer layers were likely ruined, I pulled out about 20 feet of film and threw it away, cutting a short roll from deeper into the roll and loading it into the Royal 35-M. I figured that if this roll still showed light leaks, I’d just discard the rest and try something else in the Royal at a later date.

As it would turn out, my idea of going deeper into the roll was good! The entire strip of film I loaded into an empty cassette came out mostly undamaged. There was some evidence of light leaks on the sprockets as light likely piped in through the edges, but it was little enough to where my scanner cropped it all out! Score! I had about 80, well maybe 78 more feet of “found film” to use!

Looking at the images, I was very pleased not only that the film was still good, but at how the Royal performed. I shot the film using Sunny 16, and noticed quite a few shots were a tad overexposed, so either my math was off, or the shutter was a bit sluggish at the speed I was shooting it at. Certainly nothing I couldn’t correct in post though. Another anomaly was some softness in the highlights. Taking a closer look at the lens while holding the shutter open in Bulb mode, there is a tiny bit of internal haze which caused this, but nothing that in my opinion ruined the image.

Even with the haze, I could very much see that the Tominor 45mm f/1.9 lens was on part with many 6-element sub f/2 Japanese lenses made by a variety of companies in the era. Sharpness was excellent in the center to the edges, with only the slightest hint of softness, but no vignetting in the corners. The glow in the highlights was lightly caused by the condition of the lens, but even in this current shape, I very much liked the look I got. I only shot black and white film through the camera, so I cannot comment on color accuracy, but by the late 1950s when this camera and lens were made, Tomioka was one of the premier lens makers in Japan and I have no doubt that when new and in perfect condition, the Royal 35-M was capable of stunning results.

Using the camera was enjoyable, and definitely on par with more recognizable fixed lens rangefinders made by a dozen other Japanese companies. Although I did not use the selenium meter, it was working and appeared to be accurate. I appreciated that the shutter and aperture rings on the shutter were not coupled, allowing me to freely choose whatever combination of speed and f/stop I wanted, without having to defeat some LV system. The film advance lever, while short and stubby worked fine, and I found the viewfinder to be large enough to where I could see all four corners while wearing prescription glasses.

In terms of things I didn’t like, anything I could say is well within the realm of nitpicks, such as the location of the shutter release, which I felt was too small, and squished too close to the exposure meter dial and front door covering the selenium meter. With the door open, its hinge gets in the way of your finger while pressing down on the shutter release. I also found the aperture and shutter speed rings to be a tad too thin, making them difficult to locate while looking through the viewfinder.

The Royal 35-M is a fine camera. From what little I’ve seen and read, every variation of this camera made by the Royal Camera Company was a fine camera. The best thing I can say about it is that it makes wonderful pictures, is easy to use, and is just like many other fine fixed lens leaf shutter 35mm rangefinder cameras made in Japan in the mid to late 1950s. The problem with it however, is that it is too much like many other fine fixed lens leaf shutter 35mm rangefinder cameras made in Japan in the mid to late 1950s.

The Royal 35-M is essentially a carbon copy of a multitude of Petri, Taron, Beauty, Yashica, Neoca, and probably a dozen other manufacturer’s offerings from the same period. My theory in the history section above that the JDMC was created to put an end to cameras like this probably has some truth to it, as I would suspect a customer walking into a camera store in 1957 when this camera went on sale, would likely struggle to tell the difference between it and half a dozen other very similar models.

Other than slightly different cosmetics than those other cameras, there’s not much to differentiate between them all. Depending on what you’re looking for, this may or may not be a good thing. If you just happen to really like this style of 35mm Japanese rangefinders with a fast lens, then this is definitely a camera that belongs in your collection, but if you already have one of many similar models and are looking for something new to try, buying a Royal 35-M will likely seem redundant.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Royal_35M

https://yashicasailorboy.com/2018/07/19/an-elusive-camera-the-royal-35-m/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/43063706@N02/albums/72157622471715773/

https://kellnerhank.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-reliable-royal-35-m.html

How did you process your Aristo Edu 100 film?