This is a Konica Hexar, a 35mm point and shoot camera made by Konica in Tokyo, Japan starting in 1992. The Konica Hexar was an unusually advanced point and shoot camera with a long list of options, many of which are not typically found on fully automatic cameras like this. Perhaps the camera’s best feature is its fast and incredibly sharp 7-element 35mm f/2 lens, but other stand out features are a nearly silent electromagnetic shutter, metered manual control, automatic parallax correcting viewfinder, and an optional clip-on flash which was sold with the camera new. Because of this combination of features, high price, and low production numbers the Konica Hexar has achieved somewhat of a cult status, making it a very desirable camera today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 35mm f/2 Konica Hexar coated 7-elements in 6-groups

Focus: 0.6 meters to Infinity, Infrared Active 290-Step Auto Focus with Manual Focus Lock

Viewfinder: Reverse Galilean with Projected Frame Lines, Automatic Parallax and Angle of View Correction, 0.59x Magnification

Shutter: Electromagnetic Stepper Shutter

Speeds: B, 30 – 1/250 seconds, Stepless

Exposure Meter: Silicon Photo Diode Meter with Programmed and Aperture Priority AE and Metered Manual Modes

Battery: 6v 2CR5 Lithium Battery (Camera), 3v CR2025 Lithium Battery (Date Back), (2x) 1.5v AA Alkaline Batteries (HX-14 Auto Flash)

Flash Mount: Hot Shoe, Optional HX-14 Accessory Flash

Other Features: Silent Mode, Focus Fix Mode, Various Flash Modes, EV Compensation

Weight: 536 grams, 670 grams (with HX-14 Auto Flash)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/konica/konica_hexar.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Konica Hexar was an early premium point and shoot with a lens that dates back to a 1950s Nikkor design. The camera’s long list of features, large size, simple controls, and excellent lens are the highlights of a terrific, but expensive camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for the complete package, one of the best premium compacts ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

The early 1990s was an era of great change in the photographic industry. A trip to your local camera store would have looked much different than it did 10 years prior with nearly every camera sold having auto focus and a whole slurry of automatic features. DX film encoding, auto film loading, Programmed AE and auto focus in professional level SLRs, and a whole bunch of strange looking advanced point and shoots unofficially known as “bridge cameras” adorned the shelves where manual focus SLRs, cameras with single exposure modes, and manual ISO dials once sat. The funny thing is, in just a few more years, the rise of the digital camera would further change the landscape of photography in ways the industry had never seen.

For most consumers looking to buy a new camera in 1993, there weren’t as many options as there used to be. Apart from Leicas, who were well out of the price range of the average consumer, rangefinders were extinct. Twin Lens Reflex and other medium format SLRs could still be bought, but once again, these cameras were priced for the deepest pocket professional only.

For everyone else, SLRs and point and shoots were what you had to choose from. In the SLR world, brands like Konica, Yashica, and Mamiya no longer made SLRs, and Olympus only offered fixed lens SLRs. Many brands like Exakta, Miranda, Argus, and many others no longer existed at all, at least not in any way where a consumer would buy anything from them.

In the point and shoot segment, cameras were getting increasingly more advanced, but also more simple. The amount of CPU controlled electronics were higher than ever before, modes specifically designed for macro, sports, or nighttime photography were being included in the settings, auto focus ranges were advancing from the simple three zone passive IR systems of the early 1990s to multi-zone active auto focus technologies. For most consumers, the need to know things like Sunny 16, the exposure triangle, or even how to measure distances in your head were no longer needed. You simply pointed a camera at something and pressed the shutter release, and you were guaranteed a decent looking photo.

But what if you wanted something where you didn’t have to entirely trust a CPU to decide exactly how your photo should look? Or what if you wanted a camera with a faster, more advanced lens than the 3 and 4 element f/3.5 and slower zooms that often adorned most point and shoots? Sure, you could get an SLR, but those were expensive, and big. Very few SLRs could be described as pocketable and usually required a separate carrying case to lug around.

For these consumers who wanted more than a simple point and shoot but thought an SLR was too expensive or bulky, and still wanted manual control and excellent lenses, a narrow category of cameras called the Premium Compact was created. In the early 1980s, the Japanese ceramics company Kyocera was one of the first companies to realize this segment when they started including slightly better than average Carl Zeiss lenses with T* coating on their Yashica point and shoots. Models in the Yashica T-series usually sold for a few bucks more than the competition and people took notice of their German optics. Kyocera, having licensed the Contax brand name from Zeiss in the 1970s, began releasing premium Contax compacts like the Contax T-series with Zeiss Sonnar lenses in 1984. Other brands would soon follow offering their own takes on a point and shoot camera with better lenses and more manual control, but at a higher price.

In 1992, Konica would release what at the time was the most feature filled, most premium point and shoot camera ever made. The story of how this camera came to be starts with the ill-fated Konica FS-1 SLR. When it was first released in 1979, it was the first 35mm SLR with a built in motor drive. Other features included an electronic shutter, Gallium Arsenide Phosphor TTL light meter, and shutter priority auto exposure. The FS-1 was an advanced camera for its era, but almost immediately after its release, suffered from poorly designed electronics. Many early examples of the FS-1 failed due to weak electronics, and needed to be serviced. Later versions of the FS-1 improved the reliability of the camera somewhat, but it was a poor seller, tarnishing Konica’s reputation in the SLR market.

The company would attempt to turn things around with the release of the Konica FT-1 Motor in 1983 which redesigned almost all of the weak points of the FS-1, revising the cosmetics, upgrading the meter to a Silicon Photo Diode, and a few other minor tweaks. Although the FT-1 Motor proved to be a more reliable camera than its predecessor, it could not overcome weak sales and would signal Konica’s exit from the SLR business and become the last SLR Konica would ever build themselves.

After the failure of the FS-1 and FT-1 Motor, the engineering team who built it would be assigned other projects at the company, one of which was the Konica MR.70 point and shoot from 1985 who introduced a new dual lens system which allowed the photographer to switch between a 38mm f/3.2 and a 70mm f/5.8 lens. The dual lens system was the first of its kind and would evolve into the MR.70 LX in 1987, the weather proof MR.640 from 1988, and finally the rugged Konica Genba Kantoku “site supervisor” camera.

Although the Genba Kantoku was primarily known for its large and rugged body which could stand the rigors of a construction job site camera, it added a third auto focus sensor to the camera for increased precision.

After the success of the Genba Kantoku and other advanced Konica point and shoots, the team that designed these cameras and previously worked on the FS-1 and FT-1 motor got to work on a premium Konica point and shoot which would be called the Konica Hexar.

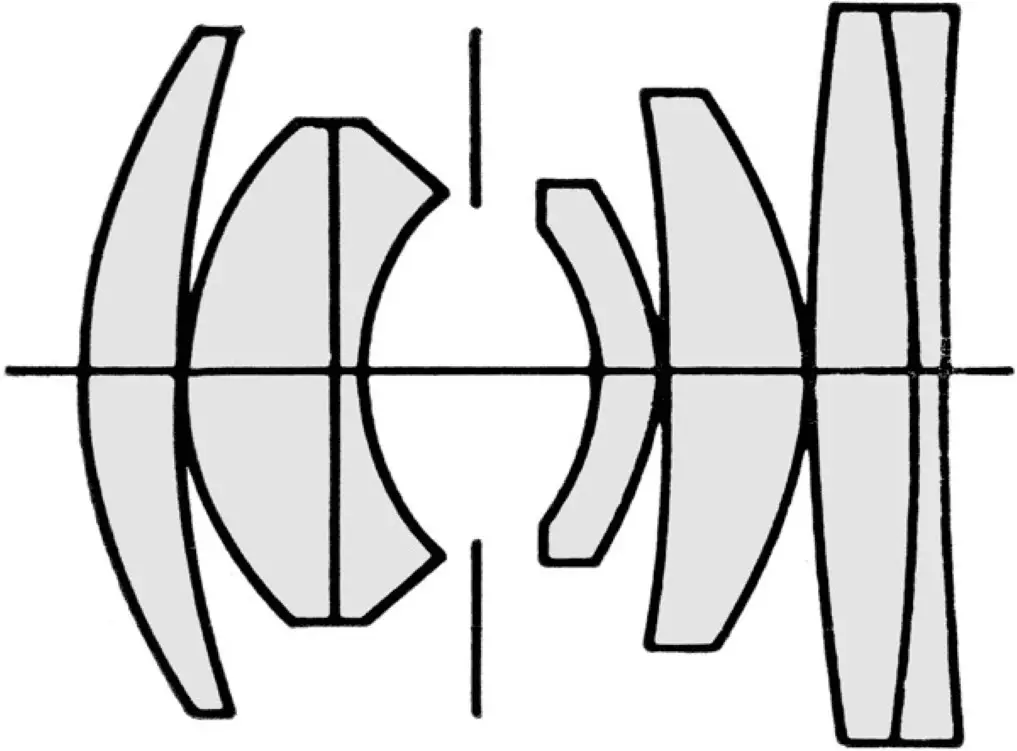

At the core of Konica’s new camera would be a 7-element in 6-group 35mm f/2 Hexar lens whose design goes back to the Nippon Kogaku W-Nikkor 3.5cm f/1.8 lens. Both lenses have a 7-element in 6-group design, but the Konica’s differed by having a slight gap between the second and third elements which gave greater negative power to the front group, which allowed Konica to fit an electronic shutter between the third and fourth element. Another slight change to the 7th element revised the curve of the rear surface which improved field flatness and reduced coma and spherical aberration.

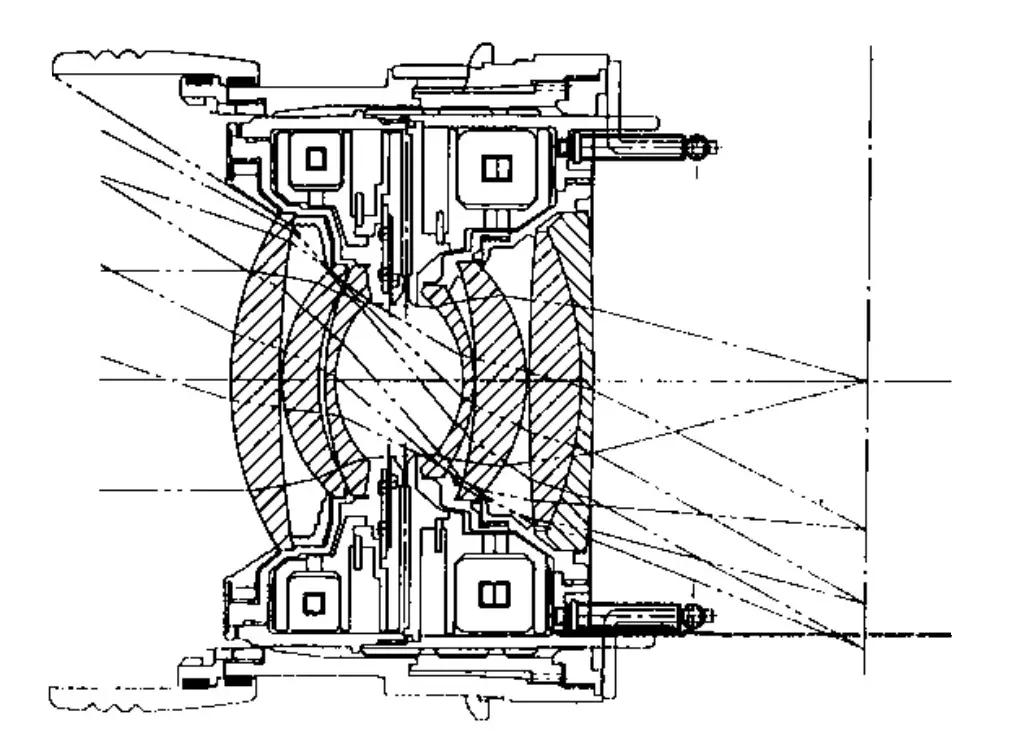

The new Hexar lens was optimized for sharpness and contrast wide open, so in order to make the most out of its capabilities, the camera needed an upgrade to the focus system. Improving on the three window design from the Genba Kantoku, the new camera used a single infrared spotlight in the center, and two rangefinding photodiodes which give the camera incredible focus accuracy. The auto focus system can detect distance to one of 290 steps, an unheard of number at a time when many cameras had systems with as little as 3 steps. In the event neither of the focus systems are able to receive a reflected IR image from the central spotlight, the focus system defaults to 20 meter, the lens’s hyperfocal distance. As one final focusing trick, the camera can be forced to infinity focus with a touch of a button or manually focused to any distance with a long press of the MF button.

The Hexar would have a number of other innovative features such as an automatic parallax correcting viewfinder, an optional HX-14 Auto flash with support for rear curtain sync, the ability to leave the leader out when rewinding film, changing the AF system to accommodate either 750nm or 850nm IR film, and a special silent mode in which the already quiet camera can be quieted further, by reducing the sound of the autofocus and film advance system by slowing them down. Rounding out the long list of features, the Konica Hexar came in a plastic and metal hybrid body covered in soft touch surfaces, and a rubber grip. The body was hefty, care of an all metal interior, and had excellent fit and finish.

When it was released in February 1992, the Konica Hexar was not only the most advanced point and shoot to hit the market, it was one of the most advanced cameras Konica had ever made. With the premium features, came a premium price. The suggested retail price at the time of its release was a whopping $1200, although the street price you were likely to pay was closer to $800. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to around $2600 and $1725 today.

When it was released, the Hexar came only in black, but some color variants would follow, first with a Gold plated version in March 1993 which came in a wooden display case to celebrate Konica’s 120th anniversary. A year later, in 1994 another anniversary edition called the Hexar Rhodium came with a champagne colored top and bottom plate and brown leather body covering to commemorate Konica’s century of making cameras.

Finally, in April 1997 came the Hexar Silver, which wasn’t a commemorative edition, but rather a less expensive version of the original camera, with a few omissions. The most significant was the disabling of the silent mode, which is rumored to because the technology ran awry of some copyrights owned by another company. Strangely, the silent mode feature wasn’t actually removed from the camera, but rather disabled. Clever owners of the camera can re-enable it by following a “Konami-code” like sequence to turn it back on.

It is probably safe to say that the Konica Hexar was not a camera the world was asking for prior to its release, but in addition to winning several industry awards in both Japan in Europe and being in production from 1992 to at least 1999 when the camera still showed up as new in dealer advertisements, it also inspired many other manufacturers to up their game in the premium point and shoot segment. Models like the Minolta TC-1, Nikon 28TI and 35Ti, may not have ever been released had it not been for the early success of the Konica Hexar.

Today, with an increase of interest in film photography there is an increase in easy to use point and shoot cameras, especially those with prestigious reputations or high end features. This has a tendency to drive up the prices of these models beyond even what they sold for new, but sadly, due to the widespread use of electronics in these cameras, plus a general difficulty in getting them fixed if something were to go wrong, spending a premium price on a premium camera that can’t be fixed is a risk. If however, you are willing to accept that risk, this is a terrific camera that has a feature set that few others had. It it easy to use, well built, and has a great lens, and even if you only get a chance to borrow one, I definitely recommend it!

My Thoughts

The segment of “premium 35mm point and shoot camera” is a somewhat controversial segment today with film enthusiasts. While a good number of examples were made in the 1990s and 2000s to help extend the appeal of higher end 35mm cameras, the problem with many of these cameras today is that due to the massive amount of electronics in these cameras, many are starting to show signs of failure, and with replacement parts non-existent, for most examples, when a premium point and shoot camera dies, it never comes back.

This causes a quandary for people looking to try one out as the prices on them are still quite high, but who wants to pay a premium price for a premium camera, that likely doesn’t work, or could soon stop working. With models like the Contax T2, Fuji Natura 1.9, and Nikon 28Ti ranging in prices between $600-$800, it certainly gives pause to anyone wanting to invest that kind of money into something that almost certainly is soon to become a paperweight. Until that day happens though, I will do my best to give you detailed reviews on as many cameras as possible, even if they’re ones that I wouldn’t personally pay the eBay asking prices for.

Such is the case with this truly mint condition Konica Hexar I came across in its original display case with flash and original paperwork. I am unsure if this camera had ever been used before, but if it did, it saw very little use as it looks brand new.

Immediately after picking up the camera, this models “premium” label becomes apparent as the Hexar feels like very few point and shoots I’ve ever handled. For starters, the camera is quite large. It is actually surprising that it doesn’t have an optical rangefinder or interchangeable lens mount. Compared to a Voigtländer Bessa R2, the Konica Hexar is exactly the the same width and height and a tad thicker front to back. Only in weight is the Hexar smaller, but not by a lot. With the flash and batteries installed, the camera weighs 425 grams which is like compared to a premium rangefinder, but still greater than most point and shoots.

The outer body is constructed of a what Konica called a “hybrid” body which is really just a combination of plastic, rubber, and metal, but the inner chassis and film compartment are all metal. The plastic parts have a soft touch matte texture that tricks your fingers into feeling something more substantial than it really is. Overall, the fit and finish are excellent and due to the large body and sparsity of controls, the entire camera has an uncluttered and clean appearance.

Up top, the camera starts off on the left immediately with an elegant silk screened “Hexar” logo. Next to it is the accessory hot shoe and film plane indicator. Skipping to the opposite side of the top plate is the combination power switch and exposure mode dial with four settings, OFF, Program, Aperture Priority, and Manual Exposure modes. Above and to the left of this switch is the soft touch shutter release button with a large metal aperture dial. The shutter release is not threaded for a cable release and allows for a half press of the shutter release to confirm and hold focus. Instead of shutter speeds as you’d expect on most cameras, Konica gave you control over apertures with a mechanical dial instead of shutter speeds, which I actually really like. When it comes to choosing between Aperture and Shutter Priority modes in a camera that offers it, I am more often than not an Aperture Priority guy. I prefer having total control over depth of field and other characteristics of different aperture sizes, than just shutter speed. Of course I like controlling both, but if I have to pick one, I’m an aperture guy, so having direct control over f/stops with a large mechanical dial is awesome. That the dial has a knurl to the edges making it easy to grip with positive feeling click stops only adds to the experience.

In between the aperture dial and hot shoe is a small LCD with a series of mode buttons to control various camera settings. In Program mode, the LCD displays the number of exposures remaining, in Aperture Priority mode, it displays EV compensation, and in Manual mode it displays shutter speeds. With combinations of buttons below and to the right of the LCD, this screen can also be used to manually set ISO film speeds, set manual focus distance, enable or disable silent mode, and when the battery is running low, a low battery warning. A dedicated button to quickly focus the lens to infinity is a convenient option when out shooting far away action shots where you don’t want to wait for the AF system to figure it out. A small recessed button labeled “R” is a force rewind button to rewind the film before you’ve reached the end of the cassette. An amazing feature of this camera which should not be overlooked is that you can manually set the ISO speed to any speed from ISO 6 to 6400. Considering most non-SLR auto exposure cameras of the late 20th century often don’t allow settings below ISO 100, to go down to 6 is an awesome feature.

While Konica figured out a way to get this tiny LCD to show all of the settings you’d need to know, its small size and that no two settings can be displayed at the same time (for example, you cannot see how many exposures are remaining while manually shooting shutter speeds), I feel as though this is a case where “more is more”. As it is, the LCD is cramped and I feel increasing its size would have gone a long way, without taking away from the clutter-free appearance of the top plate.

Flip the camera over and on one side is the battery compartment door for the single 2CR5 lithium battery, and next to it a metal 1/4″ tripod socket. While it is not common for many point and shoots to ever be mounted to a tripod, with the many different modes of this camera and its ability to expose images down to 30 seconds, a tripod socket is a must have.

The sides of the camera are mostly uneventful, with a metal door latch for opening the film compartment on the left, and the camera’s serial number stamped in the body and filled with gold paint on the right. Both sides of the camera have metal strap loops which is very convenient for long trips where you wouldn’t want to keep holding the camera.

Around back the camera has a large round opening for the viewfinder in the extreme upper right corner of the camera. As a left eye shooter, I don’t mind its location so far away from the middle, but I would suspect right eye shooters might. On the door is a clear window for reading the type of film on whatever cassette you have open and the controls for the date back. According to the documentation for the Konica Hexar, not all models have the date back. This isn’t a feature I ever use on my cameras, so I did not test it, although the manual does suggest there is a way to record date or time, which I guess could be useful. Sadly, like most cameras with date backs, you cannot select a date later than December 31, 2019.

Opening the right hinged film door reveals a very modern film compartment with electrical contacts for the dat back below the film gate and the DX contact points where the cassette goes. Film transports from left to right on a large quick load take up spool. Loading a new roll of film only requires you to extend the leader to a “Film Tip” mark stamped below the spool and closing the door. Above and below the film gate are polished metal rails, and on the inside of the film door is a large metal pressure plate with dimples, and a roller to the side, all of which are there to aide in the smoothest possible film transport. For anyone wanting to use the date back, a small battery compartment is in the door, partially behind the pressure plate. A rubber gasket on the inside of the film door seals the film compartment when closing the door, protecting it from light leaks. On mine, the rubber was still very supple with no cracks, suggesting it should have a long life. A regular foam seal around the film cassette peep hold could one day degrade and need replacing however.

Up front, there’s little to see as most of the camera’s controls are on the top plate. Above the shutter is a small window showing the focused distance set in manual focus mode or a green mark indicating auto focus. No other exposure or distance settings are visible from above. Around the front of the lens is a built in retractable lens hood, which sticks out just far enough to shield the lens from some flare, while not getting in the way of the 35mm lens. To the left of the lens on the front body of the camera is a red LED that blinks when the self-timer is set. To the left of the self-timer window is the AE sensor, which quite surprised me to see as it means this camera doesn’t do TTL metering. The lens is threaded for 46mm filters, which is a nice plus, but with the AE sensor outside the filter ring means that the exposure system will need to be manually adjusted when using most colored or neutral density filters.

The Konica Hexar lacks a built in flash, but like most premium cameras has a hot shoe for use with external flashes or speedlites. Included in the box with the Hexar is the Konica HX-14 Auto flash which offers basic speed light capabilities such as rear curtain sync and automatic distance control which changes the intensity based on the focus distance. The flash can also be partially controlled manually by setting it to “A” mode on the flash and then choosing an f/stop based on the film installed in the camera from ISO 50 to ISO 400. I did not play with this mode, so I won’t continue to elaborate more on it, but if you’d like to learn more, there is some additional information in the manual.

There is a lot to like about the Konica Hexar, but perhaps my favorite part is the viewfinder. The large round eyepiece on the back of the camera reminds me of the ones on the Leica M rangefinders. The viewfinder has a 0.59x magnification which is actually quite good, especially considering the lens is a semi-wide angle 35mm. Bright, and easy to see frame lines highlight the captured area and automatically correct for parallax. While automatic parallax correction is a common feature on modern rangefinders, this is an extremely uncommon feature to find on a point and shoot.

In the center, in place of a rangefinder is a crosshair to indicate both the auto focus and auto exposure area. Despite all of the advancements in this camera, it still only has a single AE/AF spot. The upper right corner has a focus scale that is coupled to the parallax correction feature. The scale only has two marks, one for infinity and one for 0.6m which is the minimum focus. A mark moves on a scale to give an approximation of what the distance the lens is being set to.

At the bottom of the viewfinder are 3 LEDs which you cannot see unless they are lit. Starting in the button right corner is a green LED that when lit means that focus is locked. A blinking green LED means the AF system could not determine the correct distance and you must either recompose, or switch to manual focus mode. To the left of the green LED will be two red LEDs in the shape of a + and – to indicate over and under exposure. If neither red LED is lit, then proper exposure is obtained. These lights work in P, A, and M exposure modes. In P mode, the presence of either LED means you’ve exceeded the physical limitations of the camera for the AE system to properly expose the image. In either A or M modes, the LEDs are telling you to make a corresponding adjustment to either the shutter speed or aperture to achieve correct exposure.

After handling the Konica Hexar for a bit, it is pretty clear that the people who designed this camera wanted to make the best possible camera, while still being in the realm of a point and shoot. Although the term “Premium Point and Shoot” was not in common use at the time this camera was released, it very well may have helped originate the team as this is one of the highest quality and fully featured point and shoots I’ve ever seen. The weight, size, viewfinder, and lens all scream rangefinder camera, but the fact that you can literally point it at something and shoot it…well, you know.

Of course, just because something looks like a duck, smells like a duck, and sounds like a duck, is it really a duck? Let’s load in some film and find out!

My Results

Excited to try out the Konica Hexar and seeing that it was in good working condition, the Hexar was one of the first cameras from Kurt Ingham’s collection that I shot last summer. I packed it in a bag with me on a family vacation and brought with a couple rolls of film. The two rolls of film from the gallery below are a fresh roll of Fuji 200 color (the kind made by Kodak), and a semi expired roll of Kentmere 400.

Let me cut to the chase. Holy cow, these images look great! I went into shooting the Konica Hexar assuming I’d get great images, but as I scanned each of these two rolls into my PC and I saw the incredible sharpness and detail jumping off the screen, I had to do a double take to make sure I was looking at the correct rolls, as quite simply, I have never seen images with such sharpness and detail from anything less than a top tier SLR or rangefinder before. Also, for those of you hardcore film shooters who won’t scan your film in using anything less than a perfectly calibrated Noritsu drum scanner, know that I scanned these on an Epson flatbed scanner. Laugh all you want at the stereotype that flatbed scanners aren’t good for 35mm film, these images look great!

Not that I expected anything less from a 7-element Konica Hexar (or is it a Hexanon) lens based off the excellent Nikkor 3.5cm f/1.8 lens which itself inspired many other lenses by Leitz and other manufacturers, but somehow when using a camera that doesn’t have a removable lens, your mind just somehow assumes the images won’t be as good. Sharpness, contrast, color accuracy, everything was perfect. If there was one optical characteristic I observed was that outdoors in images where the sky is present, I do notice a tad bit of vignetting, but it is the kind of pleasing vignetting that gently fades the closer you get to the edges, not the kind where there is a steep drop off sharply near the corners as if you’re about the reach the edge of the coverage circle.

I really hate the comparisons to Leicas on cameras that aren’t Leicas, but I feel comfortable saying that this is as close to shooting a Leica as you’ll ever come with while using a point and shoot camera. The Konica Hexar AF features a lens based on a classic rangefinder design, it has a huge and bright viewfinder with automatic parallax correction, a large and “full sized” metal body, full manual exposure and focus control (although it is not the easiest to use), and did I mention that lens?

I kept the camera in Program AE mode for most of the two rolls, but at times while shooting the black and white images, I did play with aperture priority mode and loved the control of the aperture via the large and very satisfying to turn dial. Combined with the match LEDs visible in the viewfinder, it was easy to forget I wasn’t shooting a classic rangefinder.

Although I applaud all of the manual exposure and focus modes, that they’re sorta buried with button presses and seeing the settings requires use of the tiny LCD, I didn’t find these as useful. I would suspect that a regular user of this camera would only choose a manual exposure more or manually focus for single shots in very specific situations, rather than shoot an entire roll this way.

One such way can be seen in my mirror selfie image and the one of the swimming pool, both of which were badly out of focus. As the only blurry images in the two rolls of film I shot, they were both ones where I had to shoot through glass. It is clear the IR autofocus system cannot see through glass, but instead focuses in the distance between the camera and the glass. This is actually a pretty common problem with many IR systems and by no means is a fault of this camera. The photodiodes that detect the IR light are seeing it reflected back off the glass, rather than through it. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, both of these situations would have benefitted from manual focus. At whatever point I shoot this camera again, and I definitely will, I will experiment with this more and maybe getting a better mirror selfie.

Besides that, there is one more “con” to this camera that often gets mentioned, which is its top 1/250 shutter speed. Why on Earth would Konica put so much time and effort into making so many aspects of this camera as good as possible, but then cripple the shutter with such a slow top speed?

While I don’t have an answer to that for you, I can say, that it isn’t as big of a problem as you probably think. As evidence, look at the images I got, both indoors, and outdoors, and I never once exceeded the limitations of the shutter. Second, when you look at cheap point and shoots or classic rangefinders with claimed 1/500 or faster shutters, it is highly likely the speeds aren’t actually coming close to hitting 1/500. I’ve seen shutter tests of cameras where 1/1000 speed shutters can have as much as 20-30% error on the slow side.

Beyond calibration though, the Konica Hexar makes most of its diaphragm which can stop down to f/22. Believe it or not, many point and shoots don’t ever tell you what their minimum aperture is, and when tested, rarely go above f/11. If you consider f/22 is stop stops slower than f/11, shooting the Hexar at 1/250 and f/22 is the same as 1/500 at f/16 and 1/1000 at f/11.

Also, keep in mind, while the Hexar is a flexible camera, it is designed for people with a discerning eye for photography. I doubt many pro photographers are going around loading in ASA 800 or 1600 speed film and shooting it in bright sunlight, and in the extremely unlikely instance where you need to do that, the lens is threaded for 46mm filters, so you can compensate with a neutral density filter.

For me, if I am going to shoot outdoors, I load in an appropriate film for that in the range of ASA 50 to 200. If I want to shoot indoors, I load in a faster film and let the camera take care of the rest. I would suspect that most owners of the Konica Hexar took that same approach and rarely, if ever, ran into an instance where they found the top 1/250 shutter speed to be a limiting factor.

If you’re not convinced, and have made it this far into this review still thinking the Hexar’s top speed is a deal breaker for you, that’s totally fine. Just use another camera!

While researching this article, I read several reviews of the Konica Hexar and all of them mention the top 1/250 shutter speed, but not a single one mentioned the biggest con to the camera, which is that the exposure meter is outside of the filter ring. I find this to be a strange, as this means that using any sort of filter other than a UV filter, you’ll need to manually adjust the exposure as the light coming into the meter is not the same as the light passing through the filter to your film. Camera designers as far back as the 1960s were cognizant of this as meters were usually relocated to inside the filter ring, or taken inside the body of the camera at the film plane.

Beyond that though, the Konica Hexar is an amazing camera. In fact, I was so impressed with using it and the images it made, it might be the most impressed I’ve been with a camera that I’ve used in a very long time. Sure, I can pick up a Leica M6 or a Nikon F5, but I’ll already have high expectations for those, but for a camera that despite what it looks like on paper, is still an electronic point and shoot camera, my expectations were seriously blown away and I am sure yours will.

Sadly, these cameras aren’t common and when found can fetch high prices, but for what it is, I would absolutely take this over any other premium point and shoot made by Contax, Nikon, or anyone else.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Konica_Hexar

https://cameraquest.com/konhex.htm

https://www.trentonmichael.com/new-blog/2018/3/31/hexar-af-kodak-proimage-100

https://cameralegend.com/tag/konica-hexar-af-review/

https://www.35mmc.com/16/07/2017/konica-hexar-review/

https://themachineplanet.wordpress.com/2018/02/25/konica-hexar-af/

The parent Nikon 35mm f1.8 W-Nikkor-C lens is available in LTM39 rangefinder mount. Pair it with your Canon 7, or your FED, and you’ll likely get the same results with zero worries about failing electronics. The total investment (especially with a Ukranian body) will be no higher.

I do have that lens in Nikon rangefinder mount and you’re right, the quality is the same. But there is a distinct difference between shooting that lens in a classic mechanical rangefinder, vs an advanced modern point and shoot camera. I get that the electronics in the Konica will eventually fail, but until that happens, I will happily keep using this camera.

A fiune lens indeed. But I mis-spoke: The S mount version is relatively affordable; the LTM39 version is several grand (if you can find one). I’ll stick with my vintage Canon LTM39 glass as it is superb and within $$$ reach!

Hi Mike,

As always, a great review… and your Hexar images are awe-inspiring! I’m wondering if an old tip about shooting though glass would help. It is to shoot at a slight angle so that the camera doesn’t really “see” the glass. Maybe it wouldn’t work with IR sensors? I don’t know. But perhaps worth a try!

Dave

Thank you for the compliment Dave! I didn’t try the “shoot glass at an angle” but I don’t think that would help either as you’d still have the IR beam reflecting off the glass, but now you’re at an angle and it would probably focus on something much farther than what you were pointing at. Then again, who knows, maybe it would work! Next time I load film into the Hexar, I’ll try this and report back.

As much as I love my UC-Hexanon 35/2 (L39 standalone re-release of the Hexar’s lens), I find it comes with moderate barrel distortion (not unlike a standard gauss lens) and severe mid aperture (f/2.8-f/5.6) focus shift (back focus) on digital Leicas.

Konica’s document says the lens was intentionally under-corrected for spherical aberration to keep the size down – which explains the focus shift, which in turn is automatically compensated by the Hexar’s AF system. For example, when shooting a subject at infinity @ f/4, the infrared rangefinder will instruct the lens to front focus a bit. Which means this lens only performs optimally when used in its native configuration – the Hexar AF body! Sort of a precursor to the modern day in-camera correction and quite a technical marvel for the early 1990s.

Hi Mike:

There is a comparison test of the Contax T2, Konica Hexar, and Nikon 35Ti, titled “Posh Point & Shootout” in Popular Photography’s September 1994 issue, beginning on page 42. This issue is available in Google Books.

I remember first reading about these cameras: “Wow, a thousand bucks is a whole lot of loot for a point-and-shoot!”

Hope you find it interesting

paul1513

Does anyone know of a repairman who will work on these? I would like to proactively have the two capacitors replaced that usually fail. Thanks.