This is a Nikon 28Ti, a premium point and shoot 35mm camera made in Japan by the Nikon Corporation starting in 1994. The Nikon 28Ti was the follow-up to the Nikon 35Ti from the year prior, widening the focal length to 28mm and adding a new flash mode and all black body, but otherwise the two cameras were premium point and shoots with titanium and aluminum metal bodies, premium lenses, and a long list of features not commonly found on point and shoot cameras. Perhaps one of the most distinct feature of both the 28Ti and 35Ti cameras is the large analog needle display on the top of the camera which shows things like focus distance, f/stop, number of exposures, and exposure compensation. Both cameras catered to a luxury crowd and carried very high prices, and as such are difficult to find today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 28mm f/2.8 Nikkor coated 7-elements in 5-groups

Focus: 1.3 feet / 0.4 meters to Infinity, Active Infrared Auto Focus, 541 Steps

Viewfinder: Aspheric Optical Viewfinder with LED Illumination and LCD Display, 92% Field of View, 0.35x Magnification

Shutter: Programmed Electronic Shutter

Speeds: 2 – 1/500 seconds, separate “Long Time” mode which allows the shutter to be open as long as 10 minutes

Exposure Meter: Silicon Photo Diode with Matrix Metering and Programmed and Aperture Priority AE

Battery: 3v CR123A Lithium Battery

Flash Mount: Built in Flash with 4 Flash Modes

Other Features: Self-Timer, Manual Focus, Infinity Focus, Date Back, Fully Automatic Film Loading and Rewind

Weight: 338 grams

Manual: https://archive.org/details/manual_28TI_OM_NIKON_EN

How these ratings work |

The Nikon 28Ti, and its sister camera, the Nikon 35Ti were two of Nikon’s premium 35mm point and shoot cameras, produced for about five years during the 1990s. With an excellent wide angle lens, a full host of auto and manual exposure and focus modes, a bright and easy to use backlit viewfinder, mode control dial, a large and very cool looking analog display up top, and a titanium metal body, there is a ton to like about these cameras. Everything about these cameras is very high quality, including the price, which puts it quite a bit higher than other 35mm point and shoots making for a less than economical purchase. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall excellence, a camera well deserving of its “premium” moniker | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, the world had become accustomed to Nikon cameras and Nikkor lenses as being at or near the top of the line when it comes to high quality cameras and lenses. Ever since the release of the Nikon F in 1959, Nikon took control of the pro market and never looked back. Even when the company released products for “less than” professional photographers, the company often struggled to make thing cheap. Nikkormat SLRs and later the company’s lineup of FM, FE, FA, and other SLRs were still considered premium options in their respective markets.

In the 1980s and 1990s when point and shoot 35mm cameras became the preferred camera for the family snapshooter, Nikon still made good stuff. Their first autofocus point and shoot, the Nikon L35AF was nicknamed in Japan, Pikaichi which translates to English as “stands above the rest” because of its excellent 5-element lens and excellent performance.

By the end of the 1980s, the Nikon Corporation would finally succeed at making true consumer oriented cameras with inexpensive prices, the company still leaned towards the high end for a large part of their product portfolio.

In 1992, when it seemed that the days of “premium” and “point and shoot” could refer to the same product, the Japanese camera maker Konica would release a true premium 35mm point and shoot called the Hexar. With a mostly metal body loosely inspired by a Leica rangefinder, and a lens that was based off the 7-element W-Nikkor 3.5cm f/1.8 rangefinder lens, the Konica Hexar showed the world what a premium point and shoot could look like.

The release of the Hexar seemed to inspire other Japanese camera makers to release their own premium takes on a point and shoot. For Nikon, the company would release two models, the first was the Nikon 35Ti in 1993 and the second a year later called the Nikon 28Ti. Both models would share the same basic layout featuring a titanium metal body with a fast f/2.8 lens and a very large and distinct analog gauge cluster on the top plate. Both the 35Ti and 28Ti would feature Nikkor branded lenses which was very unusual for a point and shoot as Nikon typically reserved that branding for their higher end SLR, and previous rangefinder lenses. Even with the release of consumer grade SLRs like the Nikon EM in 1979, the Nikkor name was usually dropped.

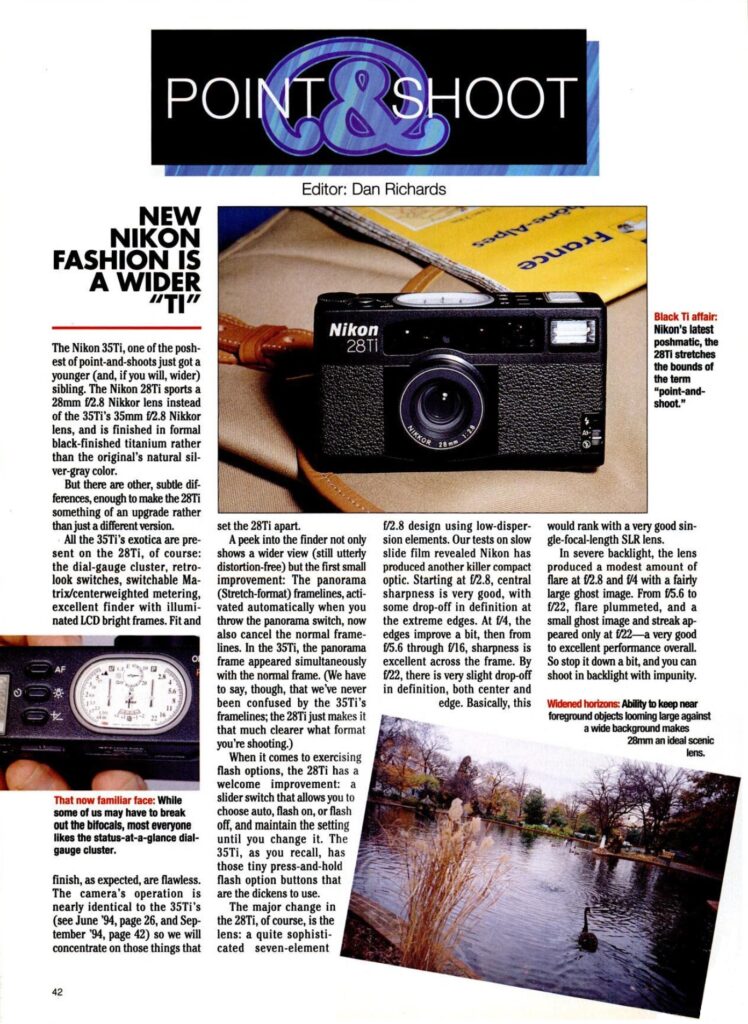

The Nikon 28Ti would come in 1994 with a wider 28mm 7-element Nikkor lens, a black instead of champagne body, an additional flash mode, a better support for panoramic photos. In a short review of the new Nikon 28Ti from the March 1995 issue of Popular Photography, the Nikon 28Ti carried a list price of $1220 with street prices between $950 and $1000. These prices when adjusted for inflation compare to $2500, $1950, and $2050 today, which almost certainly would not sell today.

In the review above, the 28mm lens was given excellent marks, calling its performance “killer” and saying that it would compare favorably to a very good 28mm Single Lens Reflex lens. It goes onto say that slight light falloff was observed wide open at f/2.8 but disappeared from f/4 to f/22, which was impressive for a wide angle lens, let alone one on a point a shoot. Additional praise was given to the bright and easy to use backlit viewfinder and “flawless” fit and finish. Very few cons were listed with one being the camera’s styling which some editors thought was understated, and at least one who wasn’t a fan of the panorama mode. Overall the review was very positive, saying that if you were a traveler who wanted a wide angle lens with precision performance and had a lot of “green stuff” in your wallet, this was the camera for you.

It is not clear how long the Nikon 28Ti or 35Ti were in production, but a point and shoot roundup in the November 1999 issue of Popular Photography still listed both cameras as current models, so its safe to say it was still being sold new then.

That the 28Ti and 35Ti were produced for at least 5 years suggests that at least some people thought they were successful, but after which time both models were discontinued, Nikon would never again release a premium point and shoot 35mm camera. This likely has little to do with any shortcomings of the 28Ti and 35Ti, but rather by then digital photography was already gaining a foothold. The demand for a premium 35mm point and shoot across the industry had almost completely dried up, but had it still been a popular segment, I would bet that Nikon would have followed up with a new model in the series.

In the years since the Nikon 28Ti and 35Ti were made, both cameras have maintained a base level of popularity as very good premium 35mm cameras, but with the recent increase in people shooting film within the past couple years, both models have risen to near “cult like” status, alongside other premium 35mm cameras made by Contax, Minolta, and Rollei. Prices for the Nikon 28Ti and 35Ti are unreasonably high and one of the few cameras whose value has appreciated since they were new.

Although terrific cameras that make excellent images, the biggest weaknesses of each model are the electronics in them which as I write this, are already over a quarter century old. As the years go on, integrated circuits, CPUs, and solder joints will continue to fail, and without any replacement factory parts available, these cameras will be come increasingly difficult to find in working condition, further raising the value of the ones that do. If you are in the market for one of these cameras, the best time to buy them has already passed you, but if you still want one today, buy quickly as prices are certain to keep going up.

My Thoughts

Marketing people love the word “premium”. The word premium evokes thoughts of high quality, luxury items, with a long list of features, improved durability, and usually a higher price tag. It doesn’t matter whether you’re talking about a car, a clothing line, a breakfast cereal, or a camera, companies produce premium versions of nearly every product as a means to showboat the best of what they can do, and maybe just get a few extra bucks from your pocket.

I’ve been thinking alot about premium compact cameras lately with my recent review of the “very premium” Konica Hexar earlier in 2024. Comparing the Nikon 28Ti to the Konica Hexar, these are two very different cameras. The Konica Hexar is a large camera with a styling that evokes classic rangefinders with a long list of features not typically found on a compact camera. It almost feels like a bridge camera, halfway between a manual control professional camera with some fully automatic features. The Nikon however, is styled more like a traditional point and shoot, with a very compact body, retractable lens, and although it does have quite a few manual controls, everything feels more consolidated.

The first time anyone picks up the Nikon 28Ti, or the similar 35Ti, their attention is almost always drawn to the huge cluster of analog needles on the top plate, but more on that later. The second however I think is the feel and heft of the titanium metal body. Titanium is often used in products due to its excellent combination of strength and lightweight, and while the 28Ti is definitely not a heavy camera, the feel of a metal bodied point and shoot is contrary to the countless number of plastic bodied cameras out there. With a a 36 exposure roll of film and battery loaded, the camera weighs in at 358 grams which isn’t much, yet it still feels substantial in your hand. Perhaps this is due to some psychological tactile link our brains have with things made of metal, but the Nikon 28Ti feels heavier than it really is.

In order to be a premium product, the Nikon 28Ti can’t only be heavy, it must feel good in the hands as well and Nikon did a good job here. The fit and finish of the camera is excellent, the pebbled synthetic body covering has a deep texture and feels quite thick, almost like the old vulcanite coverings on classic Leicas. Each of the cameras controls, especially the multi-mode dial on the top plate move with purpose and are nicely dampened, neither are too difficult or too easy to move, just like a premium camera should.

Up top, the Nikon 28Ti has a lot going on. On the left is a rather large plastic rectangle with a horizontal bar patten almost as if this was some sort of slider to reveal something beneath, but it is just a frosted viewfinder illumination window which allows light to enter the viewfinder so you can see the bright lines, autofocus oval, and the entire 7-segment liquid crystal display.

Inside this frosted window is a red LED which illuminates the viewfinder when there is insufficient natural light to see the frame lines and LCD. The use of a red LED helps reduce strain on your eyes that a bright white or blue LED might cause in a dark environment. Beneath it is a tiny LCD which when the camera is off, always has the word “off”, which I think is strange as it constantly drains the batteries when its off, to let you know it is off. With the camera on, this LCD is used to program the date back, show the charge status of the battery, and display how many exposures have been made, or if there is no film in the camera. Next to the LCD are three mode buttons for autofocus, a combined self-timer / low light assist mode, and +/- EV compensation.

Next is the signature feature of the Nikon 28Ti (and the very similar 35Ti), the large oval cluster of analog needles. The inclusion of this dial is curious and something I’ve never seen Nikon do before. As a maker of cameras and lenses, Nikon rarely took risks. From the company’s earliest days as a maker of Nikkor lenses and Nikon rangefinders, the company produced goods for professional photographers. Pros want high quality and durable cameras. When you shoot photos as your profession, you need a tool that is familiar, and works without having to think about it. Because of this, Nikon rarely implemented new technology or state of the art features in their premium cameras. Even when they did include new technologies in their lower tier cameras, they rarely were first. The company didn’t start downsizing their 35mm SLRs until the Nikon FM in 1977, they didn’t release a camera with auto focus until the Nikon L35AF in 1983 and they didn’t make a serious push into the interchangeable lens digital mirrorless market until the Nikon Z6 and Z7 in 2018.

The function of the analog display is pretty self-explanatory. Large needles point to a focus scale showing distances in both feet and meters and a separate scale for aperture with marks from f/2.8 to f/22. Both of the focus distance and aperture needles have a default position to indicate AF and Programmed AE are on. When shooting in manual focus or manual exposure modes, the mode dial is used to manually move the needle to your chosen setting. In the center pointing down is a smaller needle which indicates exposure compensation, and above it is an even smaller needle which duplicates the exposure counter from the small LCD. In addition to showing the number of exposures, this dial also shows when the camera is rewinding film, if it is empty, the self-timer is on, or “Long Time” exposures which is essentially an electronic Time shutter mode which allows the shutter to remain open up to 10 minutes.

The analog display works well and is very cool to watch. Much like the Seiko designed analog needles on top of the Epson R-D1 digital camera, the movement of each of the needles has a very “watch-like” feel to them, in fact, I would not be surprised to learn that Seiko made this display for Nikon. The analog display is very cool and is definitely something first time users of this camera would want to play with. One problem I have with it is, why? There is nothing that this display does that makes the user experience any better, and quite frankly, I think it looks out of place. I keep saying the analog display has a white background, but it is actually more like a light almond color. It sticks out like a sore thumb on top of this otherwise all black camera. I feel as though a large LCD like Nikon used on their SLRs of the era would have suited this camera better. They already had the parts to make them, why not just put one on a point and shoot? The inclusion of this feature, while very cool, is why I said earlier that it is curious as it is not like Nikon to showboat a feature like this that has no practical benefit, other than being “cool”.

To the left of the analog gauges is the silver painted shutter release with a combined power switch and exposure mode dial with settings for P, A, and T. The first two are for Programmed and Aperture Priority AE, and the T is for Timed mode, which allows you to manually control how long the shutter stays open. In the bottom right corner of the top plate is a round mode dial which is used in combination with several buttons on the camera to cycle through various options.

The base of the camera has a 1/4″ tripod socket off to the side, a small recessed manual rewind button, and the locking door for the battery compartment. The Nikon 28Ti is an entirely electronic camera, so it requires a single CR123A Lithium battery for power.

Around back is the rectangular opening for the viewfinder and to its left, two mode buttons for changing the date back settings on the top LCD. To the right of the viewfinder is a sliding switch to activate a gimmicky panoramic mode in which a movable baffle crops off the top and bottom 6mm of the exposed image area to produce 18mm x 36mm crop-panoramic photos. The film door has a plastic window on the right to read the name of the film cassette in the film compartment, and to the left is a rounded bump which acts sort of like a thumb grip when holding the camera. The film door itself is covered in the same high quality pebbled body covering as the rest of the camera.

The sides of the Nikon 28Ti are slightly more interesting than just another point and shoot. On the right is a hand strap look which when the camera was new would have had a small wrist strap attached. There is not an equivalent loop on the other side of the camera however, so there is no option to use a traditional neck strap. Above the strap loop is the film door release latch. The latch is of the “fold and twist” variety usually found on some higher end cameras like the Nikon F5 and Canon EOS-1N. On the left side of the camera is a small button which activate red eye reduction mode when using the flash. Why this option is here by itself on the side of the camera, rather than selectable with the other buttons on the top plate is an odd choice in my opinion.

With the left hinged film door open, the Nikon 28Ti has a predictably modern film compartment. Film transports from right to left onto a quick loading plastic drum. A red sticker on the opposite side of the drum, beneath the door hinge indicates how far the film leader must be stretched to before closing the door. After closing the door, powering on the camera, and pressing the shutter release, the camera will automatically pull in the film and advance it to the first exposure. The inside of the film door has a painted metal pressure plate covered in divots which reduces friction as it transports through the camera. A foam gasket around the film door peep hole, in addition to inside the door channels and near the door hinge complete the light sealing of the film compartment. This camera dates to the mid 1990s so the foam is only 30 years old, but over time will begin to degrade like any other camera and will need replacement.

Up front the only control we see is a three position sliding switch to select between Flash On, Auto Flash, and Flash Off modes. This is one area of the camera that differs between the 28Ti and 35Ti, as the 35Ti only has two modes selectable by momentary buttons for Flash On and Flash Off only. That the 28Ti uses a sliding switch that retains the flash setting instead of being momentary like on the 35Ti. Covering the lens with the camera off is an automatic lens cap which moves out of the way and allows the lens to extend when powering the camera on. Above the lens is a large plastic window with five various windows for the optical rangefinder, exposure windows, and main viewfinder. To the right of the viewfinder window is the flash.

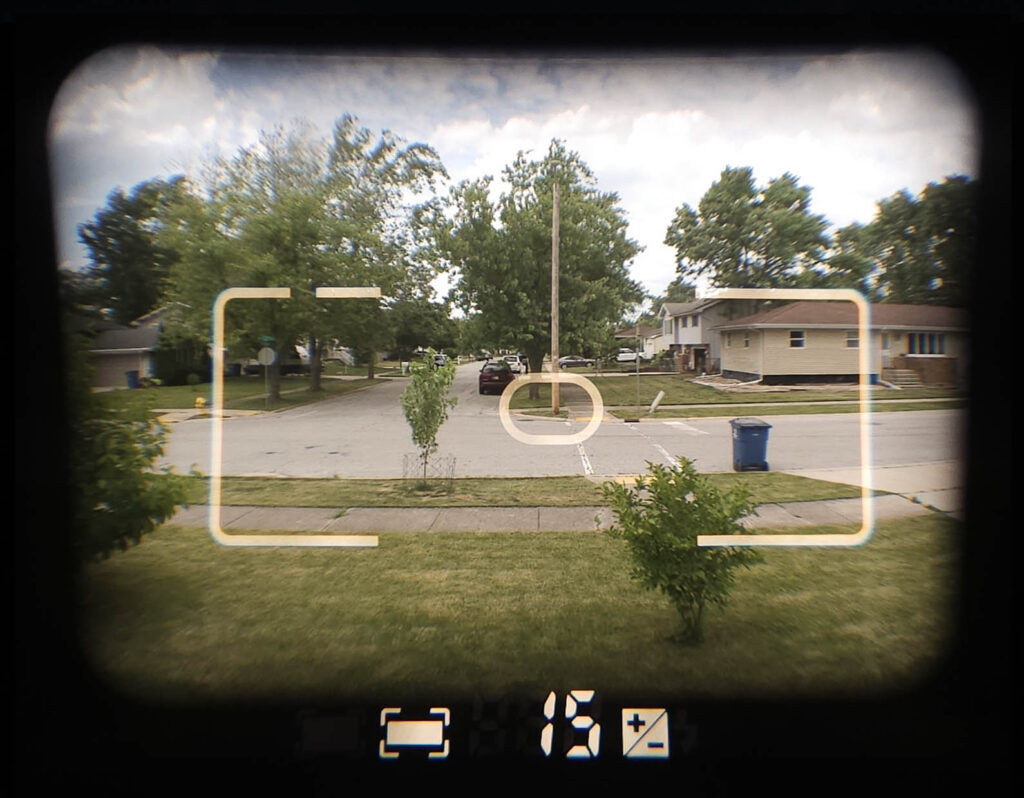

Most point and shoot cameras out there have a very similar design. There is usually some type of straight through optical design, with Albada type reflected framelines, or in more upscale models, projected frame lines. The center of the viewfinder is often some kind of oval or circle to indicate the auto focus area, and there might be some kind of analog needle or LED to indicate proper exposure or flash status, but little else. The Nikon 28Ti is not like most point and shoot cameras.

The Nikon 28Ti’s viewfinder is large and bright with projected frame lines, an oval auto focus spot, and a full information LCD display on the bottom. The light for the frame lines comes from the frosted window on top of the camera, so the viewfinder is brightest when there is light above the camera. For instances where there is not sufficient light to adequately illuminate the viewfinder, the camera automatically enables a red LED which turns the entire display red. In this red mode, the frame lines, auto focus spot, and LCD display are extremely easy to see.

The main frame lines have two additional parallax correction marks, the first of which is automatically illuminated when the camera is focused between 3.9 feet and 1.8 feet (1.2 m to 0.55 m) and a second set that is illuminated at distances below 1.8 feet (0.55 m). Unlike earlier rangefinder cameras with automatic parallax correction, the frame lines are not infinitely variable and illuminate at these specific ranges. When the camera is in panoramic mode, the main frame lines disappear and a smaller, more rectangular frame line appears approximating the panoramic image. The panoramic frame lines have a single set of parallax correction marks that are illuminated at distances below 2.6 feet (0.8 m).

Below the visible image is a 3-digit 7-segment LCD showing the shutter speed chosen by the metering system. To the left are indicators for “normal” vs panoramic mode, and to the right are icons indicating that EV compensation is enabled and whether the flash will need to be used. While each of these types of information are pretty ordinary for SLR cameras, they are not often found in point and shoots. The display in the Nikon 28Ti is the best I’ve ever seen in any compact camera, even besting that of the Konica Hexar and Contax T2. I very much appreciated being able to see the chosen shutter speed so that I could make good choices for stabilizing the camera and the automatic red frame lines in low light was a game changer. Apart from some type of through the lens EVF showing exactly what will be captured on film, the Nikon 28Ti has the best viewfinder of any point and shoot I’ve ever used.

Nikon was not the first company to make a premium point and shoot, but where many companies were satisfied just to give their cameras a slightly better lens and fancy paint job, it is clear that Nikon put a lot of thought and effort into their premium models. From the Titanium body with elegant finish, to the excellent 7-element lens, the large analog dial, and excellent viewfinder, the Nikon 28Ti sets the bar very high for what “premium” should mean. This is a great camera with great features and a great lens, but do you really need all that to make great photos? Keep reading to find out!

My Results

Both the Nikon 28Ti and 35Ti came to me in working order, and knowing that both cameras would likely work the same way, I decided to just shoot the 28Ti as it had the widest lens. I shot two rolls of film back to back, a fresh roll of Fuji 400 Superia and a lightly expired roll of Ilford FP4. Although the Nikon 28Ti is a camera with premium features, it is still a point and shoot, so I shot it like one as an everyday camera of random places I went.

Knowing full well that the Nikon 28Ti offered a great deal of features and manual control, I largely used it as a fully automatic point and shoot camera. In a couple instances, including the mirror selfie image, I tried the manual focus options and inside a local Hooters restaurant, I shot the camera in manual exposure mode, but a large number of the 36 exposures from the two rolls of film I shot were done “point and shoot”.

I had high expectations for the 28Ti and its 7-element 28mm f/2.8 Nikkor. In the short review of the camera from the March 1995 issue of Popular Photography I included above, it states that the lens on this camera is as good as an SLR lens, which is quite the praise for a point and shoot.

Upon looking at the scans on my desktop monitor from my first two rolls, I was mightily impressed. Sharpness and contrast was excellent. Although I am reluctant to call myself an expert on lens reviews as for me, a lens either looks good in the field or it doesn’t, I don’t care how it performs in a lab, my takeaway is that the Nikkor lens is as good as promised. If I had one nitpick its that vignetting is a bit more noticeable than the Popular Photography article suggests. The images of the red truck in my gallery show significant vignetting, as do other images where the sky is present. It is still within the norm for any 28mm lens though, SLR or not.

The camera also performed extremely well in both auto exposure and auto focus. In the mirror selfie, I did use manual focus, but other low light indoor shots returned accurate focus across the board.

The viewfinder is the best I’ve ever seen on a point a shoot. In addition to being decently large and bright, but the full information LCD display at the bottom with supplemental red backlighting is a game changer. There are very few point and shoots with this amount of information visible, and the red backlight is just damn cool! I did not use the camera’s panoramic mode as I find this style of switchable 35mm panoramas to be gimmicky, but from how I understand it, it seems to work well.

Beyond the viewfinder, using the camera was a joy. The camera’s ergonomics were good, with the shutter release in a logical and comfortable position. The location of the viewfinder on the rear of the camera near the upper left corner is exactly where I expect it to be and I had no issue finding the camera’s critical controls with it to my eye. And although I did not use it often, I definitely appreciated the mode dial on the back right edge of the top plate. Dials like this make the Nikon 28Ti work more like an SLR than a cheap point and shoot with mode select buttons.

The Titanium body and pebbled black finish not only looks good, but also feels good in the hand, reminding you that this isn’t just another plastic fantastic point and shoot. While I certainly would do everything in my power to not drop this camera, it has a heft which suggests it could handle small drops to the ground without breaking into a million pieces. The fit and finish of the camera’s moving parts, including the various buttons, mode dial, and film door are all very good and are consistent with a premium camera.

There is always uncertainty with electronic cameras from the era in which the Nikon 28Ti was built. How long will it keep working, when will the inner circuits short out, or the various plastic pieces inside wear out. I don’t have those answers, nor do I know of a sampling large enough of Nikon 28Ti users to tell you what the common failure points are of this camera, but one that I can predict is the motor that extends and retracts the lens each time you turn it on. Although both the 35Ti and 28Ti I had seemed to work fine, both had a concerning groan as the various gears spun, moving the built in lens cap out of the way and extending the lens barrel. I can picture in my head a bunch of off-white plastic or nylon gears, covered in 30 year old sticky lube, slowly grinding away, one step closer from complete failure. While that hasn’t happened yet, the simple act of turning the camera on and off will remind you of this generation of camera’s imminent doom.

So far in this review, I haven’t spent much time talking about the large analog display on the top plate of the camera. Hand a Nikon 28Ti or 35Ti to a first time user, and they almost certainly won’t comment on the red backlit viewfinder, the mode selection dial, or the location of the shutter release. I bet 10 out of 10 people will comment on the analog dials, and for good reason, they are really cool, adding an analog “watch-like” feel to this modern, state of the art camera. Each of the analog dials work as you’d expect, showing useful information like number of exposures, +/- EV mode, focus distance, and aperture f/stops, but the thing is, none of what’s up here make the camera better to use. Each of the things in this display could be just as useful with an SLR style LCD. None of this information is useful with the camera to your eye and requires you to lower it to see the setting. Lowering the camera to see the focus distance, or which f/stop you’re using isn’t very helpful.

I fully understand that this was supposed to be a premium camera, and with a premium camera it should have some features to stand out from the competition. The analog display certainly stands out, but I find it strange that Nikon, a company known throughout its history to not take too many risks, would go this route with a complex analog display, with what I assume is a bunch of really tiny parts to make work. Even stranger is that after all this effort, none of it really makes the camera better to use. Instead of this complex display, had there been a large LCD showing the same information, the rest of the camera would be just as good, and I suspect it would have been cheaper to produce and sell.

Clearly, the analog display is there to grab attention, and it does that well. It is neat. Only the Epson R-D1 digital rangefinder has something similar, and like that camera, it is cool, but doesn’t make the camera better. At the very least, if you pay the price to own a Nikon 28Ti, you can definitely say you have a camera unlike few other.

That little diatribe aside, both the Nikon 28Ti and 35Ti are excellent cameras with excellent lenses, excellent viewfinders, excellent exposure systems, excellent auto focus, and a long list of features. If you already have one, it really makes no sense to get the other as the difference between 28mm and 35mm isn’t much, and in my opinion, the rest of the changes aren’t worth buying essentially the same camera twice (I actually do prefer the champagne body of the 35Ti a tad more than the black body of the 28Ti).

If you’re in the market for a premium 35mm point and shoot with an excellent lens, have very deep pockets, and aren’t concerned with the imminent death of 1990s electronic cameras, the both the Nikon 28Ti and 35Ti are easy recommendations. These are without a doubt two of the best cameras of this style ever made and the best I’ve ever used. I am extremely grateful to have had a chance to play with both and tell you about them. I think you’d be crazy to buy one, but if you do, at the very least, know that you’re getting an awesome camera!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_Ti_cameras

https://casualphotophile.com/2022/06/29/nikon-28ti-point-and-shoot-film-camera-review/

https://www.thatvintagelens.com/blog/2018/3/15/nikon-28ti-a-champion-of-compact-quality

https://www.35mmc.com/10/03/2019/nikon-28ti-and-35ti-mini-review/

I stumbled over “are already over a half century old”: If I calculate correctly, it would be max. 30 years. Which doesn’t mean its electronics could not crumble, of course.

Whoops, I meant to say “quarter”.

Great review and timely for me. I bought a 35Ti not too long ago and absolutely love shooting it. I mainly bought it because I wanted the analog dials from the first time I saw it. But I never expected such perfect pictures. I had two flawless rolls and couldn’t be more pleased. When I later loaded the third roll, the camera failed and in a way that is likely what you guessed. Now the automatic lens cap goes on and off continuously and nothing else happens until you remove the battery. It is very likely a lens extension problem. I knew a failure could/would happen someday but I would have liked to use it longer. I had fun and love the look but am very hesitant to throw more money at it. Still, it was great fun while it lasted.

I’m sorry to read about the abrupt failure. Are there any repair shops that will try to work on these little jewels? Does anyone know?