This is a Steinheil Casca II, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by C. A. Steinheil Söhne in Munich, West Germany starting in 1949. It was an update to the original Casca I from 1948 adding a coupled rangefinder, a new lens mount, and having a few other changes. The Casca II was an advanced and highly featured camera, especially for one made by a company not known as a camera manufacturer. In addition to having a coupled rangefinder with combined viewfinder window showing multiple frame lines, it also supported interchangeable lenses, had a focal plane shutter with speeds up to 1/1000, and had a unique adjustable flash sync system supporting every type of flash available at the time. Both Casca cameras were unusually designed and with a long list of features also meant it had a high price. As a result, few were sold and the cameras were quickly discontinued making them very difficult to find today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/2.8 Steinheil Munchen Culminar coated 3-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Casca II Bayonet

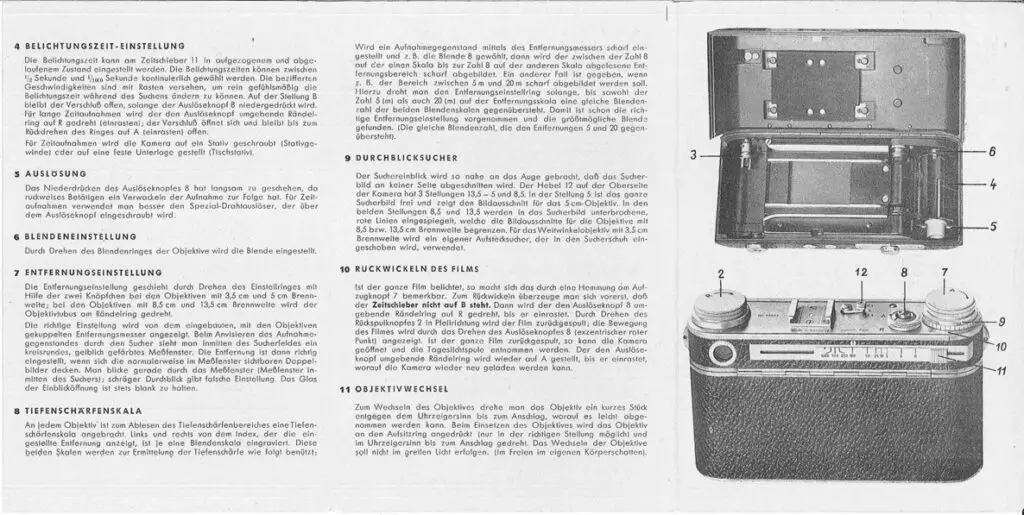

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync, if hotshoe, flash sync speed

Other Features: Multiple Frame Lines, Adjustable Flash Sync

Weight: 760 grams, 615 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Steinheil Casca II was an innovative camera with a long list of features not common in the era in which it was made. With a unique quick bayonet lens mount, multiple frame lines in the viewfinder, and one of the strangest shutter speed selectors of any I’ve seen there is a lot to like about this camera. In terms of use, it functions similarly like most focal plane interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinders out there. Since the lens mount is unique to this one camera, it is difficult to find anything other than the kit lens, but as a user, this is an interesting and very fun camera to use. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 13.0 | ||||||

History

Steinheil was a long lived and successful German optics company who was founded in 1855 by Carl August von Steinheil, a German physicist and astronomer. At the time of its founding, the company was called Steinheil Optical Institute and it produced telescopes and other optical equipment for astronomical observatories in Germany.

Steinheil was a long lived and successful German optics company who was founded in 1855 by Carl August von Steinheil, a German physicist and astronomer. At the time of its founding, the company was called Steinheil Optical Institute and it produced telescopes and other optical equipment for astronomical observatories in Germany.

In 1870, Carl Steinheil’s son, Hugo bought out his father’s interest and renamed the company to C. A. Steinheil Söhne and their focus changed from just telescopes to also include photographic lenses. One of the company’s first new lenses was called the Aplanat, a variation of the Rapid Rectilinear which was invented in 1866 by J. H. Dallmeyer in England.

The company would once again change hands in 1892 to Hugo Steinheil’s son Rudolph who would further expand the company’s business to producing photographic cameras. A variety of early wooden detective and stereoscopic cameras were produced by Steinheil, such as the Steinheil Detective Camera (Mod. I) to the right, from the early 1890s.

A large part of Steinheil’s business was never making cameras, as a majority of the company’s production was for lenses destined for other German camera makers. In the early 20th century, Steinheil earned a positive reputation comparable to other German optics companies such as Goerz, Meyer Optik, and Enna Werke München.

During World War II, like most German companies, Steinheil’s photographic operations were put on hold as the company likely produced goods for the Germany military. I found very little history about what Steinheil was doing during and immediately after the war, but shortly after the war ended, it was clear the company got back to doing what they did best, making lenses and cameras.

Perhaps the company’s location in Munich, which was in the southern part of Germany and away from Allied targets in Berlin and Dresden, spared it from bombing raids. It stands to reason that companies in areas that weren’t heavy targets during the war would have sustained less damage and been able to resume operations quicker as by 1947, the company was working on an all new top tier 35mm rangefinder camera.

Very little is known about the development of Steinheil’s new camera, which would be given the name Casca, which is an acronym of C. A. Steinheil CAmera. According to the book “300 Leica Copies” by Pont & Princelle, design of the camera shutter is credited to Karl Maiershofer of Augsburg. Exactly how much of the shutter or the rest of the camera was built by Maiershofer is unclear as I found no other reference to it either online, or in any reference book I have.

In 1948, the first of two Casca cameras would be unveiled. The first model was a scale focus only model with an interchangeable bayonet lens mount, a cloth focal plane shutter, and a distinct shape and a unique horizontal shutter speed selector on the camera’s back. The Casca had available to it four different lenses, ranging from a 3.5cm f/4.5 Orthostigmat to a 13.5cm f/4.5 Culminar, all Steinheil lenses.

The Casca was a complex and strange looking camera, with a large circular protrusion sticking out of the face of the camera with a geared wheel on top which controls focus. The focus wheel worked similarly to that of the top plate geared wheel on Contax and Nikon rangefinders, but differed in location. Another oddity of the camera was that it the film advance knob was also the film rewind knob. To rewind film, a smaller knob on the top plate must be moved to disengage the film transport and then the advance knob is pulled up and wound in the opposite direction. This design would have required a complex system of gearing under the top plate to make work and almost certainly added to the cost of the camera.

Several sites online suggest that the Casca was sold in the United States for $320, but I have found no such ads in any periodicals or reference material I have access to. I also question that price as $320 would have put it above that of a Leica IIIc, Ihagee Exakta SLR, or a Rolleiflex TLR and I just cannot see any company making an all new camera in a market they haven’t previously sold cameras in, releasing a scale focus camera with a limited selection of lenses as the most expensive 35mm camera in the world.

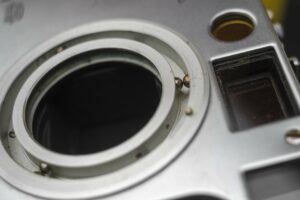

Very shortly after the release of the Casca came the Casca II a camera whose name and similar cosmetics would suggest was an updated camera, but in reality was an almost entirely different model. Like the original Casca, the Casca II had an interchangeable lens mount, but the mount was totally different from the first model. Instead of a traditional bayonet, the Casca II had a unique system in which three pairs of spring loaded ball bearings tightly grip the lens mount and can only be released when rotating the lens to a detent in the mount where the lens can be pulled off. Like the original model, Casca II lenses were made with focal lengths from 3.5cm to 13.5cm, but an additional 5cm f/2 Quinon lens was also made available.

The Casca II used a similar method for changing shutter speeds via a long sliding bar on the back of the camera, however the range of shutter speeds was expanded down to 1/2 second, improving from the original Casca which could only do 1/25. The viewfinder was changed, not only adding a coupled rangefinder, but also adding projected frame lines for the 8.5cm and 13.5cm lenses. Although a 3.5cm lens was available, the viewfinder could not accommodate it and required the use of an auxiliary finder.

Other changes to the Casca II were the removal of the body mounted focus control, a new two post flash sync system with adjustable delay for various types of flash bulbs and electronic flashes, a switch from a 3/8″ to 1/4″ tripod socket, different cosmetics on the base of the camera, plus a dedicated rewind knob that was separate from the original Casca’s combined knob.

In fact, the Casca II was so different from the original Casca that it would have been easier to simply state what was similar than what was different, and in that case it is that they both use the same kind of film and have a horizontally travelling cloth focal plane shutter.

In the “Tools and Techniques” section of the January 1949 issue if Popular Photography, an upcoming release of a Casca camera (clearly the Casca II) mentions that the camera was being imported to the United States by Instruments International of Washington DC with a list price of $300. I could find no further evidence the camera actually made it here however, nor could I find any information about the importer. Had it been sold in the US for $300, when adjusted for inflation, this price compares to a whopping $3920 today, putting it at the very top end of the most expensive cameras available at the time.

The short preview to the right describes the Casca’s features, including the standard f/2.8 Culminar lens, but incorrectly states that it has a removable back like the Contax. Whether there was at one point going to be a version with a removable back, or the magazine erroneously missed the top hinged door, is not clear.

Since I have no other information about either Cascas from the time of their release, I cannot guess how they were received but I have to imagine people would have been impressed. To see a 35mm rangefinder with such a large and bright viewfinder with switchable frame lines would have been very advanced for the time. Plus, the camera’s unique bayonet mount, sliding shutter speed bar on the back, and distinct cosmetics would have made it stand out at any trade show or camera store window it was displayed in.

In another “difficult to prove” piece of the Casca’s history is that there are reports that perhaps Ernst Leitz, makers of the Leica sued Steinheil for copyright infringements, resulting in both model’s early demise. This story too, is difficult to believe as there is so little about this camera that could possibly have stolen or borrowed anything from anything Leitz was making. Furthermore, since all prewar patents were voided after the war, even if Steinheil had blatantly ripped off the Leica rangefinder, they wouldn’t have been able to claim trademark infringement. It would have been more believable that the Casca II borrowed something from the Leica M3, except the Leica M3 didn’t exist yet, and wouldn’t be released for nearly 5 years after the original Casca’s release. If I had to pick a reason for the Casca’s short production run, it would be its complexity, cost, and difficulty in getting a camera from a company not known for making cameras, into buyer’s hands.

Exactly how many Cascas were made is also debatable. What little information exists online suggests that the total number is from a couple hundred to around 2000. A cursory image search of Casca serial numbers shows that the original Casca models usually have a serial number that begins with 5xxxx and Casca II models are 60xxx. I’ve seen original Cascas with serial numbers as high as 53553 and Casca IIs as high as 60887. While there is no way to prove that Casca cameras were produced sequentially starting at 50001 and 60001, if they were, these serial numbers suggest that perhaps as many as 3500 original Cascas and 900 Casca IIs were made.

Today, both Casca cameras fit into the category of “rare German rangefinders”. Had they been successful, they would have went head to head with the Leica and Zeiss-Ikon Contax, but for reasons that we’ll likely never know, barely made a blip on the radar and they quickly disappeared from the market.

The Casca II’s unusual design and innovative features should have wowed the market, but we now know it never happened, but that doesn’t mean they can’t still wow collectors today. It is a good thing too, that the Casca cameras are unusual because their rarity has driven up the prices sky high, putting them within reach of only the most dedicated of collectors.

My Thoughts

We’ve officially entered the area of rangefinder cameras that are so uncommon that most people don’t realize how cool they are. Surely Leica, Contax, Canon, Nikon, Minolta, and a ton of other brand rangefinder cameras are well known, but what about the more obscure ones by Mometta, Weiner, or Yasuhara?

For this review of the Steinheil Casca II, I’ll admit that I knew very little about this camera. An image or two likely crossed my path while browsing vintage camera collector groups on social media or while researching something else, but it is a camera I had never seen and knew nothing about until one day one showed up in a box at my doorstep.

Most camera collectors know of Steinheil from their lineup of rangefinder and SLR lenses made throughout the 20th century, but little is known about the short lived era in which they made cameras.

The Casca was an impressive attempt at making a premium 35mm rangefinder camera, something you wouldn’t expect from a company’s first attempt. If I were to tell you that a lens maker once tried to dabble with making cameras, you’d probably assume that first attempt would be some kind of box camera or a rudimentary scale focus 35mm focus free model.

The Casca and Casca II were quite innovative cameras with innovative features that would later become common on premium cameras made by other German and Japanese companies. It is worth mentioning that despite externally looking similar, the original non-rangefinder Casca and rangefinder equipped Cascia II are two very different cameras which I’ve discussed earlier in the section above, so what I’m about to discuss only applies to the Casca II.

For starters, the camera is quite large. It is bigger in every dimension, especially height, compared to a screw mount Leica. Sitting side by side, the Casca II sits almost an entire inch taller than a Leica IIIc, something that looks more impressive in person than reading about it online. The Casca II’s body is made of cast aluminum and tips the scales at 760 grams, which is less than had it been made of a heavier metal like brass. Considering the camera’s dimensions and complete lack of any plastic or other lightweight materials, it has good balance and feels more compact than it really is.

Up top, two large symmetrical knobs are on either side, one marked R for Rewind and the other A for Advance and they work as expected. Unlike later 35mm cameras, the rewind knob does not lift up to make rewinding easier. Next is the camera’s serial number and accessory shoe.

To the right of the shoe is a lever that chooses between three different focal lengths for the viewfinder, 8.5, 5, and 13.5. In reality, only the 8.5 and 13.5 positions display frame lines, at the 5cm position, the entire viewfinder is to be used for composition. Next is the shutter release with an A/R collar for the film transport. In the “A” position, the film advances as expected, and in the “R” position, it is deactivated for rewinding. The shutter button itself also has a red dot that spins when film advances, giving you an indication that film is properly transporting. Finally, below the film advance knob is the exposure counter. The counter itself is a ring with engraved numbers from 0 to 39. The counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made and must be manually reset after loading in a new roll of film.

A control you’d normally expect to find on the top plate of the camera is not there, but instead is located on the back of the camera. To the right of the circular eyepiece for the viewfinder is a long sliding bar which acts as the shutter speed control. A rectangular metal slider moves left and right across 10 click stops indicating shutter speeds from 1/1000 down to 1/2 second, plus one more for Bulb. This is without a doubt one of the most unique shutter speed selectors to ever appear on a camera as I cannot think of any other that works the same way. For as distinctly looking (and cool) this design is, it also has the unfortunate drawback of being very easy to accidentally change. A knurled bump on the right side of the slider is in the exact position your right thumb would be while holding the camera. Furthermore, it does not require a great deal of force to move, so regular handling or pulling the camera in and out of a camera bag can result in accidental shutter speed changes, so it is critical to check this before each and every shot. Beyond the eyepiece and the shutter speed selector, there is nothing else to see on the back of the Casca II.

Like the camera’s back, the bottom has a few interesting things. Starting on one side is a 1/4″ tripod socket. The location of the socket is not in the center of mass for the camera which means it won’t be balanced sitting on a tripod. Although this is consistent with most 35mm rangefinder cameras of the era, it is still something worth keeping in mind. Next is a sliding film door release. The letter Z indicates the film door is locked, and A is unlocked. Below the film door lock are two flash sync ports which are used for the Casca II’s unique flash sync dial to the right. A dial which adjusts the flash sync delay for various types of flash bulbs and “Elektroflash” which is the same as X-sync. A combination of German and English describe 5 different settings, most in red, but with a Focal Plane 31/Vakublitz M1 in black. The colors correspond to the shutter speed numbers where 2 to 25 are in red and 50 to 1000 are in black. With no printed manual available online, it is not clear what each sync delay is, but it is safe to assume that the fastest X-sync speed is 1/25.

The sides of the camera are nearly symmetrical with metal strap lugs protruding out of the aluminum body on both sides. The lugs themselves are strangely designed, resembling ears with a tiny hole through the center. It is not clear what kind of strap loop would fit through such a tiny hole, but upon the camera’s released, its designers must have had something in mind.

Using the door lock on the bottom of the camera, the film door is hinged on the top edge, flipping toward the top of the camera to reveal the film compartment. I have used other cameras with top hinged film doors and they all have the same problem, which is that it makes it very inconvenient to load film in the camera as the door keeps wanting to slam shut. With the lens attached to the camera, it is impossible to lay the camera face down with the door open, without it toppling over. Remove the lens however and it will rest flat, but it seems like an awkward process to have to remove the lens in order to set the camera down on a flat surface to load film. With the lens attached, you must delicately balance the camera to avoid accidental closures.

The Casca II normally comes with a removable take up spool. One was not included with this camera when I received it so I am uncertain what it looks like, but I found that a removable spool from an Ihagee Exakta or Exa (any version) works well. If you don’t have an Exakta spool handy, the plastic inner core of a 35mm cassette will also work, but it doesn’t quite sit perfectly. I think it should be fine to use, but will require you to tape the leader to the spool, and there is a chance the film will transport slightly crooked. An interesting feature of the film compartment is a spring loaded platform that holds the take up spool in place. To unload and load in a new roll of film, press down on this platform and it will lock into the lower position, allowing you to easily insert the take up spool. When the spool is in position, gently press the platform to the left and it will spring back to its normal position.

Beyond the oddities of the top hinged door and compatibility of the spools, the rest of the film compartment is standard fare. Film transports from left to right, across a normal 24mm x 36mm film plane with dual film rails above and below the gate. The inside of the film door has a black painted metal pressure plate covered in divots to reduce friction on the film as it transports through the camera. I have no evidence of this, but the Casca II may be one of the first 35mm cameras to have a pebbled pressure plate as this feature didn’t become common until the mid to late 1950s. There are no light seals of any kind to protect the film compartment from light leaks, but the camera seemed to not need it as I did not encounter any leaks during my tests.

Looking down upon the 5cm f/2.8 Steinheil Culminar, the lens looks like a normal rangefinder lens with a focus scale closest to the body and the aperture ring closest to the front. The focus scale is indicated in meters only, and has a depth of field scale and a red R index mark for IR film. Focus is changed on the lens using one of two handles that stick out about 90 degrees from each other, making them very easy to locate with the camera to your eye. The aperture ring has f/stops from f/2.8 to f/16 and turns smoothly without click stops.

Up front, the Steinheil Casca II has a unique appearance, unlike most other cameras. With a large chrome face place, flanked by pieces of leather body covering, a bronze colored rangefinder window and two very large, especially for the 1940s, rangefinder and viewfinder windows, the camera certainly looks unique. But the general appearance is not the most unique thing you’ll see with the Casca II, rather it is the lens mount, which strangely, is not the same as the rangefinder-less Steinheil Casca I.

The Casca II is technically a bayonet mount, but rather than using “ears” like pretty much every other lens mount, it employs three sets of spring loaded ball bearings that grip the lens at three indents on the back of the lens. To remove the lens, there is no lens release button, you simply grip the lens and give it a firm counterclockwise twist and it the ball bearings release, allowing you to easily pull the lens off. The total movement to release and attach the lens is very short, I’d guess about 10 degrees, which makes the process easy to do one handed. To put the lens back on, you must line up the three sets of ball bearings seen in the body, with three indents on the lens, press the lens into the ball bearings and then give it a firm clockwise twist to lock it into position. For as complicated as this sounds, it actually is quite easy to do. Perhaps too easy as a quick twist of the lens can result in it falling off.

Note: In the gallery above, I struggled to capture the red frame lines outdoors, so I took two images against a mirror where they were easier to see. Another issue popped up where the frame lines were crooked inside of the viewfinder. This is likely due to a fault in the frame inside the camera has come unglued from its correct position. This has no impact while shooting the camera with a 5cm lens, however.

There is a lot to like about the Steinheil Casca II, from the unique sliding shutter speed selector, strange ball bearing bayonet lens mount, to the camera’s overall cosmetics, nothing quite prepares you for what I think is the camera’s best feature, its viewfinder. The Casca II’s viewfinder is large and bright, offering two different telephoto frame lines which only appear when a switch is in the correct position. Although a large and bright viewfinder and adjustable frame lines isn’t exactly unheard of in a 35mm rangefinder camera, for one released in the 1940s it is. The Casca II’s viewfinder and coupled rangefinder is comparable to the one from the Leica M3, yet it came to market a full four years before the revolutionary Leica M-series rangefinder. Looking at other 35mm rangefinders available in 1949 when this camera was made, companies like Leitz and Kodak were making Leica and Retina rangefinders with squinty viewfinders barely larger than a piece of rice.

With the top plate switch in the 5cm position, no frame lines are visible, you must use the entire visible viewfinder to compose your image. I couldn’t find any technical data on the Casca II, but it does not feel like the viewfinder is quite 1:1, but it is close to life size. With the switch in either the 8.5cm or 13.5cm positions, red frame lines appear in the appropriate spots to frame for those focal lengths. The main viewfinder has a slight bluish tint and the circular rangefinder patch is tinted yellow, giving excellent contrast. If there’s one disappointing part of the otherwise excellent viewfinder is that the circular rangefinder patch is pretty small, and not at all close to the Leica M3s. Still, for 1949, the Casca II’s viewfinder and rangefinder were unmatched by anyone else. I cannot prove this, but if there is a chance Leitz designers had seen a Casca II while designing the M3, it is very likely that this was the benchmark they aimed to beat.

Overwhelmingly, the Steinheil Casca II is an impressive camera, especially coming from a company known better for making lenses. It is clear that whoever at the company was in charge of the camera’s design had no intention of copying anything being done by other German camera makers. Other than the format of film and the size of the image, this camera has nothing in common with a Leica.

Of course, any time you go against the grain and try something new, you’re bound to miss the mark on something. The Casca II isn’t perfect and after handling it for a few minutes, a couple cons are evident, but are they enough to take away from the enjoyment of shooting an otherwise really cool camera? Let’s find out!

My Results

The Steinheil Casca II’s name came to the top of the queue in December 2023 right before the holidays and coincidentally, we had an unusually warm patch of weather one weekend, so seizing a rare opportunity to go out shooting, I loaded up the Casca II with an expired roll of Kodak Plus-X 125 and took it out shooting. Although I have a decent supply of bulk Plus-X expired in the early 1990s, this was a 20-exposure roll probably from the late 1970s or early 1980s but I still felt it would shoot close to box speed. For the second roll, I loaded in some semi-expired Fuji 400 color so that I could see what the uncoated Culminar could do.

Before I get to the results, it is quite obvious something was going on with the expired Kodak Plus-X 125. While the exposures were close to box speed, there is some obvious mold that affected the film, resulting in what looks like tree roots all over the images. This clearly has nothing to do with the camera, and rather just one of those things you encounter when shooting expired film. For what it’s worth, in some of the images, I actually quite liked the look and had I known this was going to happen, I might have been able to use it to better creative effect.

Images from the f/2.8 Culimar were good, but definitely showed some limitations of the design. When stopped down in good lighting, sharpness and contrast were as good as any 3 or 4 element lens out there, however when opened up or shot in less than ideal lighting, some issues arose. I noticed some softness and lack of contrast, especially in indoor scenes. The condition of the Culminar lens was generally good, but there was a little higher than usual amount of front surface scratches which likely contributed to this.

Moldy roots aside, I much preferred the black and white images better, as the uncoated optics resulted in some washed out colors and a general lack of “pop”, part of which can be explained by the late December muted colors I shot in, but I suspect would have still been there on a warm and sunny spring day. That the black and white images looked better shouldn’t be a surprise as the film choices at the time of this cameras release would have heavily favored black and white, and perhaps an example with a perfect lens might have been better.

For all the differences the Casca II offers from a typical German rangefinder, the act of shooting it felt surprisingly familiar. Once again, that this camera was built and released in the 1940s feels so much like a camera from a decade later is quite the accomplishment. The ergonomics of the shutter release and the double focusing handles on the lens made adjusting the camera with it to your eye a pleasure. The large and bright viewfinder was definitely a huge plus, although the lack of any sort of parallax correction took away from a perfect experience. The adjustable red frame lines are imminently cool, however since I didn’t have access to either of the accessory lenses that would have required these frame lines meant I couldn’t benefit from them.

By far, the biggest issue I encountered while shooting the camera was how easily you can accidentally change shutter speeds. My technique for shooting test rolls of film in cameras is to use them to their strengths. One way I do this is to avoid the fastest and slowest shutter speeds because those are the ones which are most likely to be off. With a focal plane shutter, fast speeds can result in capping and slow speeds can result in stuck curtains or times that are way off. As a result, I tried to limit myself to shutter speeds of 50, 100, or 250, yet the number of times my fingers would accidentally move the shutter speed slider caused me some concern. I had to condition myself to check the shutter speed before each and every shot, even if I had just taken another exposure a moment sooner. In my opinion, the movement of the slider doesn’t feel overly loose, so my guess is this is how the camera would have been new. For as cool as it looks, accidental speed changes is almost certainly the reason why no other camera maker used a shutter speed system like this.

The Casca II is a super cool and great looking camera that has a surprising number of modern features for a 1940s camera, yet it was not successful. The reasons for this are many, but the most likely is that the overly complicated design, coming from a company not used to building premium cameras, resulted in extremely high prices keeping customers away. It also probably didn’t help that two cameras called the Casca I and Casca II had such wildly different designs and an incompatible lens mount. If you were in the market for one camera, you’d have to buy all new lenses if you ever wanted to upgrade.

If I could go back in time and give some advice to the people at Casca who build these cameras, I would have completely scrapped the first model. Release the Casca II first with the ball bearing lens mount and then release a rangefinderless Casca I later, but with the same lens mount and body. Get rid of the sliding shutter speed dial altogether and go back to a regular knob like everyone else was using, and expand the lens selection to include other German optics companies. While Steinheil lenses weren’t bad, they didn’t have the prestige or brand recognition of Zeiss or Schneider lenses. Finally, figure out a better distribution channel. That this camera never made it to the US was a big challenge, especially for Germany’s early post war economy that critically depended on an influx of western money.

Overall though, the Casca II is a super cool camera. That Steinheil chose a unique path with its design and features is one of the reasons this camera is so sought after today. There were tons of Leica copies out there and had they made yet another LTM bottom loading 35mm rangefinder, no one would have noticed. I’ll applaud Steinheil for trying something new, they just tried too much new stuff. As a result, we have a rare camera that looks different from anything else out there, and that means collectors want one. If you have deep pockets and are tired of the same old same ole, this is the camera to get!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Steinheil_Casca

https://cameraquest.com/casca.htm

https://sites.google.com/site/harrissonphotographica/home/the-casca-cameras

https://forum.xitek.com/thread-1511942-1-1.html (in Chinese)

I’m puzzled that steinheil would mount a lower-rank three-element Culminar lens on such a top-end camera. Why not a Quinon or a Quinaron?