This is a Monte 35A, a 35mm scale focus camera produced by Shinsei Optical Works in Tokyo, Japan starting in 1953. The Monte 35A was a subtle update to an earlier Monte 35 in which the shutter release was relocated to the top plate, an accessory shoe was added, and some minor cosmetic changes were made. All Monte 35 cameras share the same specs, a 50mm f/3.5 Monte Anastigmat Lens, collapsible leaf shutter with top 1/200 shutter speed, and an all metal body with oversized knobs. The Monte 35A has decent build quality, but is symbolic of the Japanese camera industry at a time when a huge number of one off models were released by unknown companies who came and went without much notice.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 Monte Anastigmat coated 3-elements

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: SKK Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/200 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 512 grams

Manual: None

In what could possibly be the shortest review I’ve ever written, this is the Monte 35, a 35mm scale focus camera by a Japanese company called Shinsei Optical Works in 1953.

Using all the resources I have, all of the books in my personal library, and all of the saved bookmarks I’ve accumulated over the years, I could find nothing about Shinsei Optical Works other than they made this camera and another called the Monte S in 1953. The lone example of a Monte S I’ve found credits the company as Seito Opt. Co. Sugiyama’s Guide to Japanese Cameras has a single image of the Monte S, which appears to be a very similar camera with similarly spec’d lenses and shutters. The example on the left comes from the Voncabbage Collection and has a Yosimar lens and KOC shutter which I’ve not seen on any Monte 35s I’ve seen online.

Beyond that though, there is no history of the Shinsei Optical Works that produced these cameras. A Google search for the company name does turn up a modern company called Shinsei Optical Co., Ltd, but according to their Company History on their website, this company was incorporated in November 1966, so they are likely different companies with similar names.

Between the Monte S and Monte 35, the latter is by far the more successful model as they show up for sale fairly often whereas the Monte S can’t be found anywhere online. A quick eBay search for “Monte 35” produces six examples for sale. This certainly isn’t a high number, but that at any given time at least one is for sale suggests that at least a few of these were made.

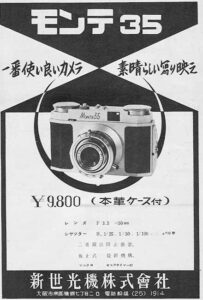

While researching this article, I found a single undated ad for the Monte 35 on an archived Japanese website that shows a price of ¥9800 which places it slightly above simple cameras like the Pax 35 and Riken Ricohlet.

Throughout its production, the Monte 35 had several cosmetic changes, most notably in the typeface of its name. A Google image search for the camera produces versions with logos written in black and red, some in cursive and not cursive, and some where there is a dash between Monte and 35.

In addition, two versions of the camera were made, one with the shutter release on the shutter itself, and another with a top shutter release. Most sites refer to the top shutter release version as the Monte 35A. It is not clear whether this was an official designation, or a moniker applied by collectors to differentiate between the two. The Monte 35A also has an accessory shoe on the top plate and has a body with a different finish than the earlier version.

Some sources online suggest that the Monte 35 may be related to a Czech camera called the Meopta Etareta. Looking at the two cameras side by side, I’ll admit the body shapes and contours of the covering are almost identical. In addition, both cameras have similarly large advance and rewind knobs, both have collapsible shutters, and similarly spec’d lenses and shutters. Beyond that though, the ergonomics of the camera are different, as as the locations of things like the shutter release, exposure counter, and viewfinder. In addition, the Etareta predates the Monte 35 by at least half a decade. I struggle to connect the dots between a low production Czech camera and Japanese company which little is known. It is possible that some European traveler brought their Etareta to Japan and someone used it as inspiration for a new camera, or its possible that there’s just only so many ways to design a simple 35mm camera and the similarities in design is just a coincidence.

The Monte 35 in my collection is inoperable as the shutter was completely seized. An attempt to flush it with naphtha was unsuccessful as I could feel some grit inside the shutter. I’m sure a full CLA could have restored functionality to this camera, but its low value, plus the fact that I probably have 100 other cameras I’d much rather spend the money on for a CLA means this one goes back on the shelf in inoperable condition.

Despite its lack of functionality, I can say that the build quality of the camera seems decent, at least above average compared to other entry level early 1950s cameras I’ve handled. The lack of things like a rangefinder or a more advanced shutter or lens would not have been an issue for the type of customer this camera would have been marketed toward. A Japanese language ad from 1953 suggests a retail price for the Monte 35 of ¥9800 which would have put it in between the Samoca 35 and Pigeon 35 cameras at ¥7500 and ¥10500 respectively. I found no evidence this camera was exported to the United States, so I am unable to come up with an inflation adjusted price in US dollars.

The body is very solid and appears to have some type of painted clear coat finish, which on the bottom plate is starting to yellow. Unlike earlier Montes that have a plain brushed metal body, the one on the Monte 35A looks a little more worn than earlier models. The synthetic body covering is in good condition and shows no signs of cracking or peeling.

Up top, I really like the large advance and rewind knobs, which if this camera had worked, would have made it ideal in cold weather conditions where someone was wearing gloves. Similar large dial cameras like the Kodak Signet 35 were made with the US Signal Corps in mind. While there is no reason to believe there was any military use planned for the Monte 35, it would have worked. Unlike the earlier Monte 35, the Monte 35A relocates the shutter release to the top plate and adds an accessory shoe, somewhat cluttering the top plate. A manually resetting exposure counter is in the middle and counts the number of exposures already made on the current roll.

Shutter speeds, aperture, and focus are all controlled from the front, as you’d expect from any leaf shutter camera. A large number of Japanese leaf shutter cameras had shutters made by different companies like SKK, TKS, and KOC. The camera shown on the camera-wiki page for the Monte 35 shows a “Monte” branded SKK shutter which is different from the one on mine. More than likely, these cameras were assembled from a hodge-podge of parts that were available at the time, so subtle control differences exist. Despite which shutter you have, they all appear to have the same range of speeds from 1 second to 1/200. I’ve not seen any Monte 35 cameras with anything different.

Loading film is straightforward in the film compartment. The viewfinder is small, but usable and with no other exposure information visible. A small lever on the front of the camera in front of the advance knob is used to deactivate the transport lock for advancing the film. Operation of the camera is pretty simple, with the biggest caution being that you have to remember to extend the lens before shooting. Looking inside the film gate, you can see the top plate shutter release disengages when the lens is collapsed, so pressing it will not do anything unless the shutter is properly extended.

When I first decided to review the Monte 35, I picked it because I wanted something quick that I wouldn’t have to do a lot of research on and could type up quickly. This particular camera was inoperable as the shutter was stuck open. You can see through the lens in the image of the camera back, and no amount of naphtha was getting it to close, so I figured this could be a ‘dead camera’ review.

Then, as these things do, fate intervened and on a late night eBay “browse”, I stumbled upon another Monte 35 for a price I couldn’t ignore. The second Monte was an earlier version with a black logo, lens mounted shutter release and unpainted bare metal body. The camera looked to be in nice shape so I bought it.

When it arrived, the shutter was also not working but at least it was closed. As I did with the first, a couple quick squeezes of naphtha and it started to fire. I figured, what the heck and loaded in some Jessop 100 film, which is a rebranded Ilford 100 film which was commonly sold in the UK back in the 90s and early 00s.

After shooting the test roll and looking at the images on my scanner, I noticed that several had prominent light leaks and of the ones that didn’t nearly every image was out of focus. I am pretty good at estimating distance on a scale focus camera, especially when shooting things far away, so that I missed focus on the entire roll suggests something else is wrong with the camera. Perhaps someone before me attempted to take apart the lens and didn’t line up the elements correctly, who knows. While it can be disappointing to get an entire roll of misfocused images, I still felt pretty good about what I got, and could see through the failure to estimate what kind of camera this could be in perfect working condition.

To my surprise, the parts of images that I did get in focus, sharpness was quite good. I also noticed a lack of significant vignetting near the edges. Additional softness was present near the corners, which I suspect would have been there even if the camera was working correctly, but not any more than you’d expect from an economical 1950s Japanese camera with a simple triplet lens would produce. I should point out that the Monte 35’s camera-wiki page suggests the Monte Anastigmat is a 4-element lens, which I have my doubts for as very few cameras in this segment would have had a lens like that. I believe this to be a much more typical triplet.

Earlier in this review, I compared the Monte 35 in price to the Samoca 35 and Pigeon 35 and after seeing these images, have no problem suggesting that image quality would have been on par with those cameras as well. Simply, the Monte 35 would have been an affordable 35mm camera for the aspiring Japanese photographer looking to get a balance of good quality, without spending a lot of money. The camera has a good build quality, a decent lens, a flexible 8-speed shutter, and a usable viewfinder. The Monte 35 wouldn’t have won any awards, but it wouldn’t offended any one either.

I was glad I had the chance to shoot the camera, because in addition to seeing the images, I found the experience to be generally positive. I would have preferred the top plate shutter release of the later model, but the shutter mounted one of the earlier version wasn’t difficult to use. The Monte 35’s film transport is not coupled to the shutter, so that means not only do you have to remember to manually cock the shutter before each shot, but you also need to deactivate the double exposure prevention before advancing the film to the next shot. This is done by flicking a small lever in front of the film advance knob while rotating it. The size of both the advance and rewind knobs are quite large and very easy to grip. If you’ve ever handled a Kodak Signet 35, the size and experience are very similar. I found the location of the film transport lever to be easy to reach with my right index finger while still being able to rotate the knob in one smooth motion.

My biggest complaint about the design of the camera, which is present in both the red and black logo Monte 35s I have, is that the film compartment is a bit crude, especially the exposure counter sprocket. This part of the camera has very sharp edges which if you don’t load the film correctly, can tear through the film. In my first attempt to load the camera, I absolutely shredded the perforations on the Jessop 100 film. Once I removed the damaged film and tried a new strip of film, I got through the roll without a problem, but upon developing it, I saw damage at the beginning of the roll from the sprockets. Running my fingers over the teeth, and they are very sharp. Other surfaces in the film compartment have unnecessarily angled edges as well. Although these other surfaces did not cause any problems with the film, they do suggest a lack of craftsmanship, that would have been there in a more upscale camera.

Beyond that though, the Monte 35 was a winner. I like the design of the camera and find both the red and black label cameras to be attractive additions to my collection. These are not high value cameras and they’re not super common, but if you manage to find one in anything close to working condition, as long as you don’t have the same focus issues I did, you will be rewarded with a nice roll of film if you choose to shoot it. And if you don’t they’ll look neat on your shelf.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Monte_35

https://cameracollector.net/shinsei-monte-35/

https://endoscopy.jp/moto/camera/camera_repair/monte35/index.htm (in Japanese)

Hi, I just had a look in my 12th edition of McKeown’s and found that I bought one of the Monte 35, Dec. 2017 for 25 dollars, the book value is $ 50-75. The camera was built in ca. 1953. The Monte S has in your pictures a Kodak type bayonet flash connector. Was it maybe made for the US market?