This is a Zenit-6, a 35mm SLR camera made by Krasnogorski Mekhanicheskii Zavod (KMZ) in the former Soviet Union between the years of 1964 and 1968. The Zenit-6 was part of a series of new leaf shutter SLR cameras produced by KMZ that use the Zenit C-mount which is a variation of the DKL bayonet mount. The Zenit-6 was identical to the Zenit-4 in every way other than badging and that when new, it came with the Rubin-1 zoom lens as standard. The Zenit-6 was an ambitious camera for the Soviet market and had a coupled selenium meter, an interchangeable viewfinder, and an all new body unique among other Zenit SLRs. It was produced for a short period of time and as a result, very few were made, making them difficult to find today, especially in Western countries.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 37-80mm f/2.8 Rubin-1C coated 14-elements in 11-groups

Lens Mount: Zenit C-Mount (47.58mm Flange Distance)

Focus: 4.5 feet / 1.3 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: KMZ Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ Viewfinder match needle

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 1940 grams, 902 grams (body only)

Manual (HTML in Russian): http://www.zenitcamera.com/mans/zenit-6/zenit-6.html

Manual (Original Scan in Russian): https://mikeeckman.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Zenit6_manual.pdf

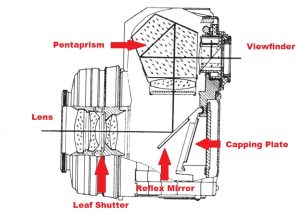

In the 1960s, a shift was happening in 35mm SLR design. Going back as far as some of the earliest Speed Graflex and Kodak SLRs from the early 20th century focal plane shutters dominated the reflex camera. The simplicity of the design and relatively low cost to build these shutters meant that they could be adapted to a wide range of cameras. When the earliest compact SLRs were built in the 1930s, nearly all of them had focal plane shutters as well.

While focal plane shutters had their merits, they were not ideally suited for flash photography as early shutters had sync speeds as low as 1/25th of a second. Flash sync aside, most focal plane shutters were made of cloth and were very fragile, not only from accidental touches by a careless finger while loading film, but also they were prone to pin holes forming in the cloth material as early rubberized coating sometimes would flake off, or burn if left in direct sunlight.

For rangefinder and TLR cameras, leaf shutters solved two of these problems in that they had flash sync speeds up to 1/500 (and sometimes higher), plus the shutter leaves were made out of a more durable material which was not prone to pinholes and was usually located in between lens elements, further protecting them from damage. While leaf shutters had their merits, they were not ideally suited for SLRs as their forward location would interfere with the reflex mirrors needed for an SLR.

In 1957, the German shutter company, Friedrich Deckel GmbH released a new type of leaf shutter which could be used in SLRs along with a new bayonet interchangeable lens mount. Although these new Synchro-Compur leaf shutters were still located forward of the reflex mirror, they had additional parts which allowed them to remain open while composing your image through the reflex finder, with an additional capping plate behind the mirror to protect the film from light.

Shortly after the release of their new Deckel bayonet mount and Synchro-Compur shutter, Kodak AG in Stuttgart released their first Retina Reflex SLR, and Voigtländer in Braunschweig released the Bessamatic, both 35mm SLRs using the Deckel mount and shutter. In the years to come, additional leaf shutter SLRs would be made by other companies like AGFA, Edixa and Braun. In addition, several Japanese camera makers like Kowa and Topcon would make their own copycat designs using shutters designed by Seikosha.

The rising popularity of leaf shutter SLRs did not escape the Soviet Union, whose robust camera industry monitored what other companies were doing, and upon seeing the benefits of leaf shutter SLRs, decided to make their own. A team of engineers and designers in Krasnogorsk, Russia, near Moscow were led by G.M. Dorsky and began work on a new Soviet leaf shutter SLR. Initial design work of the as yet unnamed Soviet SLR was based on the Voigtländer Bessamatic. Although the camera would not end up looking like the German camera it was inspired by, it shared many of the same features, including a copycat Soviet leaf shutter, and a very similar bayonet Zenit C mount.

Zenit C Mount vs DKL Mount Although very similar in look, the Zenit 4, 5, and 6 do not use the DKL mount. The biggest difference is in the flange distance, which on a DKL mount camera is 44.70mm, and on the Zenit is 47.58mm. Differences in bayonet configurations prevent you from mounting Zenit lenses to any DKL mount cameras, but amazingly, other DKL mount lenses will mount to a Zenit for macro and close-up work, however you cannot focus to infinity.

The new SLR would be manufactured by KMZ and be part of the Zenit line, although it would share almost nothing in common with existing Zenit cameras, which at that time were still very primitive. In addition to the new central leaf shutter and C mount, the new Zenit would have a removable pentaprism which allowed the user to use a waist level finder and any others had they been developed, it would be the first Soviet SLR with an automatic resetting exposure counter, and the first with a rapid rewind lever on the side with fold out handle. The signature feature was what KMZ called “semi-automatic” operation, the new camera wasn’t capable of auto exposure, but could couple the selenium exposure meter to a match needle visible in the viewfinder allowing for extremely easy exposure setting.

When it was released in 1964, the camera was released in three configurations, the Zenit-4, Zenit-5, and Zenit-6. The differences between the three were that the Zenit-4 would come with a standard 50mm f/2.8 Vega-3 lens, the Zenit-5 would have a built in battery powered film advance, and the Zenit-6 would be identical to the Zenit-4, but would come with an all new Rubin-1 zoom lens which itself was based off the Voigtländer Zoomar, which was available on the Bessamatic.

A fourth model in the series was called the Zenit-11, and despite the higher model number, would have been an entry level camera without an exposure meter. Only prototypes of the Zeni-11 were made as the camera never made it into production. Strangely, in 1981, another camera called the Zenit-11 would be released, but would be entirely unrelated.

When the Zenit-6 was sold, it often came in a custom leather case, allowing the Rubin-1 to remain attached, but facing down. Included in the case were two 77mm filters.

Along with the standard Vega-3 for the Zenit-4 and 5, and the Rubin-1 for the Zenit-6, the following lenses were also made for the Zenit C mount:

- Mir-1 37mm f/2.8

- Jupiter-25 85mm f/2.8

- Tair-38 133mm f/4

- Helios-65 50mm f/2

- Teletair-200 200mm f/5.6

- A revised Rubin-1A was produced in 1967 which changed the focal length to 37-75mm f/2.8

The Zenit 4, 5, and 6s were made with the logo written in both Roman and Cyrillic letters, but the Roman letter “ZENIT” cameras far more common suggesting more of these were sold for export than domestically. As is often the case with many Soviet cameras, I was unable to find any marketing or promotional material for the Zenit-4, 5, or 6. Most likely these cameras were sold in the UK and probably Germany, but I was unable to find any pricing material for them. Considering their much higher level of complexity compared to a Zenit-E, the cameras likely sold for quite a bit more.

The Zenit-4, 5, and 6 were all discontinued in 1968 and would end up becoming the only Soviet leaf shutter SLRs ever made as future Zenit SLRs would stick with cloth focal plane shutters. According to sovietcams, the Zenit-6 is the least common of the three with only 8930 made, compared to 19,740 and 11,616 of the Zenit-4 and 5 respectively. With a 4 year run and a total production of just over 40,000 total cameras made, this series of Zenit cameras are some of the least common ever made. Compare those numbers to the contemporary Zenit-E of which greater than 3 million were made over 21 years, it is fair to say these cameras weren’t that successful.

If the inspiration for the Zenit 6 was the Voigtländer Bessamatic with Zoomar lens, apart from a vague similarity to the lens and the same basic lens mount, there’s almost nothing else in common between the two. Keeping in the tradition of large and heavy Soviet cameras, at a weight of 1940 grams, the Zenit-6 outweighs its German inspiration by over 300 grams. That’s not to say the Bessamatic is a small camera, but at a weight with the Zoomar of “only” 1624 grams, it not only looks smaller, but feels it too. Where the Bessamatic has a certain elegance in its design with soft round corners, the Zenit has tall shoulders with boxy corners.

It is clear by just looking at the two, the Bessamatic and Zenit-6 are very different cameras, but so are their lenses. The Zoomar and Rubin-1 share only a similar zoom range and same f/2.8 maximum aperture, but are otherwise different lenses. In addition to cosmetics, the push/pull zoom on the Voigtländer lens is replaced with a less elegant rotating barrel on the Soviet lens. While many zoom lenses change focal lengths with a twist of the wrist, the very large diameter of the barrel makes the Rubin a bit more difficult to manage. That you can quickly go from wide to tele with a quick press of your thumb using the Zoomar, the Rubin is very difficult to zoom using a single motion. I am unsure of why the Soviet lens makes this critical switch, but it definitely doesn’t work as well.

In addition to a fundamental change to how the two lenses zoom, the advertised zoom range between the two is not the same either. Where the Zoomar clams a range from 36mm to 82mm, the Rubin-1 is 37mm to 80mm. In reality, differences of 1-2mm in focal range are difficult to detect. While looking through both lenses, I could not tell a difference so I am unsure if there really is a difference, or if the differences is a technicality. If the latter is true, it wouldn’t be a surprise as many lenses give a focal length which is an approximation. You’d be surprised at how many 50mm lenses aren’t actually 50mm.

In an effort to not focus only on the cons of the Zenit-6 and Rubin-1, I was quite impressed with the build quality of both the camera and lens. The Zenit-6 has a very high build quality, which in my opinion is consistent with the “professional” KMZ Start released in the late 1950s. It is clear that the designers of the Zenit-4, 5, and 6 had not only high aspirations for features, but also build quality. Soften the corners a bit and remove all references to anything Soviet related, and you could very easily pass this camera off as an early 1960s German design.

Lens aperture is controlled with a knob on the left side of the top plate just like the Bessamatic. Instead of fitting a tiny rewind knob in the center of this larger knob, the Zenit relocates it to the side of the camera. Rewinding film is as quick and easy as it is on other modern SLRs, just at a 90 degree angle. The opposite side has a large curved exposure counter which automatically resets when opening the film back and finally a film type reminder dial. A rapid film advance lever is on the back edge of the camera, which actually works well as the tall height of the camera would make a top plate film advance lever uncomfortable. Likewise, the shutter release is on the front edge of the camera, in easy reach of your right index finger.

While it should be pretty clear the Zenit-6 is hardly a copy of the Bessamatic, but if there was one area where this is extremely obvious it is in the viewfinder, or more specifically, the removable viewfinder. It would appear that KMZ had some professional aspirations when designing these cameras as they saw fit to make the pentaprism removable, allowing for other viewfinder types, such as a waist level finder to be attached. I do not believe any other viewfinders ever existed, but had they continued to series, perhaps some prevision focus or perhaps even CdS metered finders might have become available. Removing the viewfinder is incredibly easy, almost too easy however, as it is held on only by friction. Simply slide the prism towards the back of the camera and once you overcome a small amount of resistance, the entire thing comes off. I think some kind of lock button would have been a good idea to prevent accidents.

Around back is the large round opening for the pentaprism viewfinder. Next to it is the film advance lever. Considering the tall height of the Zenit-6, the location on the rear of the camera is ideal as it is in a comfortable location for your right thumb. To the left of the eyepiece is the KMZ factory logo and the camera’s serial number. The Zenit-6 uses the typical Soviet date code in which the first two digits are the year the camera was made. This particular example is from 1968, the last year of production for these cameras.

Looking down atop the Rubin-1, there are the familiar shutter speed and aperture control rings on the lens mount like you’d see on DKL mount cameras. These rings are coupled together and only the shutter speeds can be directly changed here. Since Zenit C and DKL mount lenses have no aperture control on the lens itself, adapting these lenses to other cameras requires a complicated adapter which adds back aperture control.

As an added bonus, with the Rubin-1 mounted, two metal strap loops exist on the lens barrel allowing for you to securely attach a strap to it in this location, which gives the camera better balance than trying to support everything by the strap lugs on the body.

With other DKL mount cameras, lenses cannot be swapped from one manufacturer to another. You cannot mount a Kodak Retina Reflex lens to a Voigtländer Bessamatic or a Edixa Electronica, and vice versa. Knowing this limitation and that the Zenit-6 doesn’t even have a DKL mount, that didn’t stop me from trying anyway. While writing this review, I can confirm that the Rubin-1 does not mount to any DKL mount SLR I own, but surprisingly, their lenses do mount to the Zenit-6. I was able to mount lenses for the Kodak Retina Reflex, Voigtländer Bessamatic, and Edixa Electronica to the Zenit-6. With these lenses mounted, the shutter and aperture control still worked, however I was unable to focus to infinity. With the lens set to the maximum distance, I found that objects about 6 feet away were in focus. With the lens set to 3 feet, objects about 1 foot were in focus. So while I wouldn’t quite call this “macro” it did allow for better close-ups than either the Rubin or Vega lenses did.

Loading film is uneventful. The right hinged door reveals a pretty typical film compartment for the era with the most notable exception being the film pressure plate is made from glass. Everything else is metal except for the large diameter, single slotted take up spool which is plastic. A felt light seal is along the hinge edge, but otherwise required no attention to prevent light leaks. I’ve found that economically priced cameras often skimp on quality in the film compartment, but the KMZ Zenit-6 shows no such signs of ‘corner cutting’.

The viewfinder is large and reasonably bright, especially when compared to other SLRs from the 1950s. There is some vignetting visible and the corners have a rounded shape, which cuts off part of the image. This is not an entirely unusual thing to see in old SLRs, but I’ve never found an explanation for why this happens. In the center is a large and very easy to use split image focus aide, not unlike those found in Ihagee Exaktas of the same time period. Around the split image is a large swatch of ground glass which absorbs some light, so using the camera in low light, even with the lens wide open, is a challenge. I was unable to see all four corners while wearing prescription glasses, although I was able to get close.

On the right of the focus screen is the coupled match needle which works similarly to other German and Japanese SLRs with the same feature. A thick needle with a large circle on the end is controlled by the aperture control, and a thin needle is connected to the selenium cell. At whichever point the meter needle passes through the circle from the aperture control, proper exposure is obtained. The most common use for this camera is to set a shutter speed close to whatever the combination of film speed and lighting is most appropriate, and make fine tweaks using the exposure control knob on the top of the camera. If the available light it beyond the range of the aperture control knob, change shutter speeds until a combination can be found. This style of exposure control was often referred to as “semi-automatic exposure”. While nowhere near as automatic

As I played with the Zenit-6 before using it, I became more and more impressed with it. While not as sleek and compact as the Voigtländer Bessamatic that was the supposed influence for this camera, the Zenit-6 did feel like it was a bit better put together than a typical Zenit 3 or E. Reasonably sure the camera was in good operating condition, I loaded in some Kodak Plus-X 125 that I had a bulk roll of and took it out shooting.

As I learned that true DKL mount lenses could be mounted to the Zenit-6 but that they wouldn’t focus to infinity, I thought it would be fun to try out a couple and get some closeups. Leaf shutter SLRs are notorious for having rather long minimum focus distances, so this was a good opportunity to get close with a couple lenses I had.

A Word About Lens Compatibility It should be obvious that the Zenit-6 was not designed to work with true DKL mount lenses. Although they do fit, and will allow you to see through the viewfinder, I found that the shutter would not fire with every lens mounted. Two lenses I tried which wouldn’t fire were the Schneider-Kreuznach Retina-Xenon 50mm f/1.9 from a Retina Reflex IV and the Voigtländer Septon 50mm f/2 from an Ultramatic CS. My best guess is that there is some difference on the faster lenses which causes the lens not to couple correctly. But with the Voigtländer Color-Skopar from a Bessamatic Deluxe, it worked fine, so I shot a second gallery of images using this lens on the Zenit-6.

I’ll comment on the second gallery first. As expected the Voigtländer Color-Skopar lens did an excellent job, rendering images that were sharp corner to corner, making excellent use of the contrast and shadow detail offered by the expired Kodak Plus-X 125 film. While I did not shoot any color film in this camera, I have no doubt the images wouldn’t have continued to look spectacular, because quite simply, that’s what Color-Skopars do.

If there was one difference that I really enjoyed about this combination is that all DKL lenses are known for having relatively long minimum focus distances. On a Bessamatic, the Color-Skopar bottoms out at just under 3.5 feet. Comparing to an M42 Asahi Takumar 50/2 and a Nikkor 50/1.4 lens from the same era which goes down to 2 feet, this is still significant. Since the Zenit-6 has a longer flange distance than a DKL mount camera does, mounting the Color-Skopar means that it is unable to reach infinity, however it has the advantage of being able to focus closer than it should. While I didn’t take any exact measurements, I’d say the minimum focus was around 1.5 feet, allowing me to get much closer than that Color-Skopar would ever get by itself on the camera it was intended for. I quite enjoyed being able to take some closeups with this combination and it made me long for actual DKL mount lenses that could close focus.

As for the first gallery, I shot about half of the images with the Rubin-1 zoom lens, and the other with a 50mm f/2.8 Vega-3 lens from my non-working Zenit-4 (which itself is very similar to the Color-Skopar). By car, the images from the Vega-3 were far superior to those from the Rubin-1. Normally, I’d have to split them in separate galleries, but a quick look at the images above, you can very easily tell the images shot with the Zoom lens. Had I not previously shot another Rubin-1 converted to M42 screw mount and gotten images of dubious image quality, I might have thought something was wrong with this lens. If the Voigtländer Zoomar was an early design of poor optical quality, the Rubin-1 is a Soviet copy with even less quality control.

Images shot with the Rubin-1 were not only soft, but no matter how I focused the lens, nothing was sharp. In addition, I got strange shadows and light artifacts which resemble light leaks, but I only saw them with the Rubin-1 mounted, suggesting there’s some kind of internal flaring or perhaps light bouncing around inside the lens causing strange artifacts. I didn’t hate the images shot with the Rubin-1, but they were clearly not up to par of the Vega or the Color Skopar lens.

Lenses aside, shooting the Zenit-6 was quite enjoyable. Although I’ve enjoyed shooting other Zenit cameras, they’re clearly more rudimentary compared to contemporary German and Japanese cameras. The Zenit-6 however, is quite a nice feeling camera. Build quality was very high, the viewfinder was very good, and all of the cameras controls were in ergonomically ideal locations and worked as well as they would on any other camera. In fact, compared to a Kodak Retina Reflex, this particular Zenit-6 was smoother and easier to operate than the German Kodak. Certainly, that doesn’t mean that all Zenit-6s will be this way, but in the most ideal of conditions, these cameras are quite nice, and one of my all time favorite Soviet cameras I’ve ever shot.

My only real nit pick is in its size and heft. This is a large camera. Mount the Rubin-1 to it, the weight escalates to an astronomical 1940 grams (~4.3 lbs). While the Bessamatic and Zoomar combo isn’t light either, that camera’s more rounded edges and shorter top plate makes it feel significantly more compact than this tall and heavy Zenit.

Size aside, the Zenit-6 is a terrific camera. I’d even go as far as to say, it is the nicest Soviet SLR I’ve ever shot. I am extremely pleased not only to have this camera in my collection, but that it worked so well, it am already looking forward to the next time I can take it out. I’ll just be sure to leave the Rubin-1 at home!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Zenit_6

http://www.zenitcamera.com/archive/zenit-4/index.html (in Russian)

http://www.photohistory.ru/index.php?pid=1207248179057456 (in Russian)

https://www.sovietcams.com/cameras/detail/4szmy6rwsytbztnracwfnd7hme

I’m not really sure what purpose this next link serves, but it is a very well done 3D rendering of the Zenit-6.

https://www.fab.com/listings/d2410510-64df-4b98-ba46-3b90e796429e