This is an Alpa Reflex, a 35mm single lens reflex and rangefinder camera made by Pignons S.A. in Ballaigues, Switzerland between the years 1944 and 1952. The Alpa Reflex was the first generation of Alpa cameras and is one of only a very few reflex cameras to also feature a coupled rangefinder. The Alpa Reflex has an innovative camera with features that would become standard on SLRs to come by other manufacturers and was the forerunner to the very successful line of Alpa Alnea and later SLRs produced throughout the mid 20th century. Built with the precision and reputation of a Swiss watchmaker, Alpa cameras are considered to be highly sought after devices both for their build quality but also their rarity. The Alpa Reflex uses the company’s unique Alpa bayonet and featured lenses made by top tier French and German lens makers.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/2.9 P. Angénieux Alepar coated 3-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Alpa Reflex Bayonet, rangefinder coupled

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Waist Level Coupled Reflex Viewfinder and Coupled Split Image Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: P (Bulb), 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: None

Weight: 558 grams, 504 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Alpa-Reflex is one of the earliest 35mm SLR cameras ever made, and has the distinction of also having a fully functioning coupled rangefinder, allowing for ‘best of both worlds’ usage. The Alpa-Reflex is remarkably compact and light weight. I found both the waist level finder and horizontal rangefinders to be easier to use than later Alpas, and the collapsible triplet lens, while not up to par to some other SLR lenses I’ve shot, produces images with good image quality. The Alpa-Reflex is a historically significant, attractive and well made camera that makes good images and is a lot of fun to use. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for one of a kind styling, combination of features, and historical significance | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

History

The history of the Alpa camera can be traced to a man named Yakov Bogopolsky, a Russian Jew born in Kiev in December 1895. Not much is known about Bogopolksy’s younger years, but we do know that he moved around a lot, and with each new location, he changed his name more than once.

At some point in his youth, he relocated to Switzerland and by 1914, had enrolled in college in Geneva to study medicine. Now known as Jacques Bolsky, he would eventually change his field of study to mechanical engineering and would show an interest in photography, namely motion picture cameras.

By 1923, Bolsky had designed his first 35mm cine camera, known as the “Bol Cinegraphe” which made its debut at the Swiss National Exhibition of Photography. The Bol Cinegraphe was unique in that it could be used both as a motion picture camera, but also a projector. The camera attracted enough attention that Bolsky had received financial backing from some bankers and a man named Charles Haccius, and formed his own company, simply known as Bol S.A.

Over the course of the next several years, Bolsky and Haccius would design a variety of cinema film cameras. Earlier models used 35mm film, but due to the rise in popularity of smaller film stocks, they would primarily create 16mm film cameras. One of the company’s first successes was the Bolex, a feature rich 16mm motion picture camera that had interchangeable lenses using the cine C-mount.

The Bolex was quite popular and sold well, and as a result would become the name of the company at some point in the 1920s. Bolex would design a variety of different 16mm and eventually 8mm variants of the Bolex, but would run into financial trouble around 1929. At this time, Bolsky would reach an agreement to merge with the Swiss company Ernest Paillard & Cie who made a variety of products like gramophones, typewriters, and music boxes. On September 30, 1930, Jacques Bolsky would sell a majority of his assets and patents to Paillard who would continue manufacturing Bolex cameras under the name Paillard-Bolex.

Bolsky would continue working as a chief designer for Paillard until around 1935 at which time he ventured out on his own. It was during this time Bolsky had his earliest ideas to make a 35mm camera. Both Leitz and Zeiss-Ikon had already seen success with their Leica and Contax rangefinders, but Bolsky wanted something more. The idea of a through the lens reflex camera was already being worked on by Ihagee with the Exakta, but early SLR designs were slow and very bulky, plus the dark viewfinders reversed the image, making quick composition difficult. For those looking for snapshot photos, viewfinder or rangefinder cameras were superior as they offered brighter viewfinders that oriented the image as it was in real life, allowing for quicker composition and exposure.

Jacques Bolsky decided that the best approach to building an all new 35mm camera was to give it both a reflex viewfinder and a traditional viewfinder and rangefinder. It is not clear exactly when Bolsky first began work his new camera, but the first prototypes were shown in 1939 as the Bolca I. The Bolca I had a transversely mounted rangefinder in addition to a mirror box offering through the lens composition. Several prototypes of the Bolca were created with names such as the Teleflex and Viteflex, which perhaps were other names considered for the camera.

This first series of about 20 cameras were given serial numbers in the 10,xxx range and were referred internally as Series A cameras. The prototypes successfully combined some of the best features of the Leica and Contax with that of the Exakta, offering both a true reflex and rangefinder design, but in addition to that, the camera was much smaller and lighter weight than any SLR the world had seen. The camera had a very short flange focal distance, eliminating much of the bulk required of a traditional mirror box. In addition the first lens chosen for the camera was a collapsible SOM Berthiot Anastigmat 50mm f/2.8 triplet which when collapsed, further added to the compactness and portability of the camera. It was thought that Bolsky envisioned his new camera appealing to those who traveled in the mountainous regions in Switzerland where the camera was made. With such a small form factor and a collapsible lens, the camera would easily fit into a satchel or small handbag.

Other features of the prototype cameras were a horizontally traveling rubberized cloth focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/25 to 1/1000, a bayonet lens mount allowing for quick lens changes, a shutter release that did not rotate while firing, cassette to cassette film transport with the ability to rewind film, double exposure prevention, and a clever mirror up feature that allowed the reflex mirror to swing out of position when collapsing the lens.

Additional Reading: An excellent resource for much of the historical information and serial number production comes from the book, “Alpa: 50 Jahre anders als andere” by Lothar Thewes. The book is entirely in German, so for English speakers, you’ll need to find a way to translate it, but if you do, it is a worthwhile resource to find.

During this time while the prototype cameras were being developed, Jacques Bolsky was forced to flee Europe to escape Nazi Germany’s anti-Jewish sentiment and he emigrated to the United States, settling in New York where he changed his name to Jacques Bolsey. Work continued in his absence and in 1941, a final design for the new camera was settled upon and the name chosen for the camera was Alpa-Reflex. The first copies of Alpa-Reflex cameras were produced in early 1942 and were largely the same as the final Teleflex and Viteflex with the only major change being the addition of a slow speed escapement which extended slow shutter speeds down to 1 second. In addition a few varieties of 50mm lenses were offered, produced by SOM Berthiot and P. Angenieux.

Production of the first Alpa Reflexes were given serial numbers in the 11,000 range and were internally referred to as Series B cameras. At the same time as the release of the Series B Alpa-Reflexes, a version of the camera without the reflex finder was also produced and was called the Alpa-Standard. Apart from the lack of a reflex viewfinder, the cameras were identical otherwise.

Although the Series B cameras were well received, some problems with the design of the camera, namely the types of cassettes used for film transport and the thickness of the lens bayonet mount was found to be poorly suited to rugged use required some updates to the camera. Fewer than 600 Series B cameras were produced with the highest known serial number being 11,567.

A new series of upgraded Alpa-Reflex and Alpa-Standard models were released in 1944 which featured a revised film transport with a non removable take up spool and an all new bayonet lens mount which had a different arrangement of flanges.

The new camera would be called the Series C, and keeping in the tradition of incrementing sequential serial numbers, the Series C cameras were supposed to be in the range of 12,xxx, but due to a production mistake, were all given an extra 0 and were numbered in the 120,xxx range making them the only Alpa cameras with a six digit serial number.

Due to an entirely different lens mount, lenses built for Series A and B cameras were no longer compatible with the new bodies, however Pignons SA offered an upgrade path for owners of the earlier cameras to swap out the front plate of the camera with one featuring the new bayonet, ensuring that all future lenses would be compatible with their cameras.

A total of 700 Series C cameras were made between late 1944 and early 1946. For the first time, lenses with focal lengths different than 50mm began to be offered. In addition, Series C cameras were the first sold outside of Switzerland, and for the rest of the world were the introduction of the Alpa camera. Jacques Bolsey, now operating his own company in New York City, the Bolsey Corporation of America, began importing his own camera for sale in the US as the Bolsey Reflex.

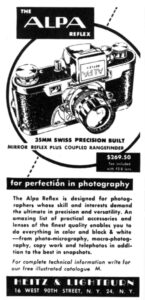

Later, Karl Heitz of New York would also import cameras as the Alpa Reflex. For all exported cameras, the serial numbers remained sequential to Alpa branded ones in Europe. In a 1948 ad to the left from Heitz & LIghtburn of New York, the Alpa-Reflex could be purchased with an unknown 50mm f/2.8 lens for $269.50. When adjusted for inflation, this price compares to just under $3500 today, making the Alpa cameras quite an investment for anyone considering purchasing one.

In mid 1945, a revision to the rangefinder coupling was made which required an almost complete redesign of the front of the camera. Until then, the coupling between the lens and rangefinder was visible just inside the lens mount and could easily be damaged while removing or installing the lens. In addition, the metal used was very thin and could fall out of calibration easily. A change was made to how the rangefinder coupling worked, whcih had the side effect of removing two large screws that were located in the bottom corners of the lens mount. These new cameras were called Series D models and are easily distinguishable from earlier models due to the lack of these two screws. The Series D Alpa-Reflex and Alpa-Standard models returned to a 5 digit serial number starting with 13,xxx and would be made through mid 1947 with the highest serial number being number 15,020.

In 1947, Series E cameras began to appear with serial numbers in the 20,xxx range. Early Series E cameras were very similar to Series D cameras with the biggest changes being some improvements to the reflex mirror assembly. Although initially not being very different from the earlier Series D cameras, two major changes would happen during this series, both in 1949 that did not warrant a new name or a new range of serial numbers.

The first was in autumn 1949 with the addition of flash synchronization to the Alpa. Different varieties of flash sync were made through the life of the camera, first only supporting FP bulbs, but later ones offering electronic flash sync. The second change was a switch from the waist level reflex finder to a new prism viewfinder which oriented the image correctly, without the horizontal reversal of the waist level finders. The first use of a prism on a 35mm SLR was on the Italian Rectaflex a year earlier and on a Zeiss-Ikon prototype SLR called the Contax. Alpa-Reflexes with the prism viewfinder were named the Alpa Prisma Reflex and were sold concurrently with non prism Alpa-Reflexes. Despite the addition of flash synchronization and the option for a prism viewfinder, these cameras were all considered part of Series E and did not get their own range of serial numbers.

The Series E Alpas would be the last of the first generation of Alpa SLRs before the redesigned Model 4, 5, and 7 would make their debuts in 1952. The highest known serial number of the 1st generation was 25,148, but it was actually a repaired earlier model from 1954 that was issued a new serial number. A few cameras, build with leftover original parts were produced throughout the years, the most recent being in 1976. This resulted in some gaps in the sequential serial numbers which makes getting an accurate count of how many were made, but it is safe to say that around 5000 Series E cameras were built, which if you add the totals from all five ranges of cameras, means that a total of about 8000 first generation Alpa SLRs were made.

Alpa would go on to produce a variety of successful SLR models from 1952 until the final Alpa 11si “Anniversary Editions” from 1989 giving them an incredible 50 year run from initial prototype to final model. That the camera stayed in production as long as it did was even more impressive considering the low volume output of such a small Swiss company, compared to the more well established camera behemoths from Germany and eventually Japan in the second half of the 20th century.

Today, all Alpa models are often at the top of the most desirable cameras to collect. The diversity of all the models produced, the quality, design, history, and exclusivity of the Alpa brand adds appeal for those who collect. That these were not mass produced cameras with production numbers in the realm of a typical German or Japanese camera maker, means that less Alpas are available for purchase, which drives prices up. A “common” Alpa model in rough shape can often still fetch prices of $500 and up with the more rare Luxus or anniversary models approaching $10,000, making them unaffordable to all but the most deep pocketed of collectors. If you are new to collecting, there are certainly more affordable options, but there’s also nothing quite like an Alpa, so if this is a camera you’d like to pick up, then it is definitely worth saving up for.

My Thoughts

Back in 2019, I picked up an Alpa Alnea Model 7 from a local estate sale and I remember the excitement I had as I was driving home with it. Alpas had perpetually been out of my price range and not knowing anyone who would ever loan me one, I thought this was a brand of camera I’d never have a chance to try out.

As I worked on the review for that camera however, I came to the conclusion that I didn’t really like that camera that much. While it had a gorgeous looks and I loved the Kilfitt Makro-Kilar lens that came with it, I didn’t enjoy shooting it. The biggest issue I had was the 45 degree angled viewfinder and dark prism. Since a critical component of using a camera is being able to see through the viewfinder, I could tell this was not a camera I’d come back to often, if ever.

Realizing my lack of excitement for it, I had an opportunity to trade it to another collector for a majority payment towards my Kodak Ektra, so I took it and ended up with the Ektra which I valued more.

With my fix for shooting Alpas subsided, I stopped looking for them, but then one day when I was least expecting it, I had the opportunity to pick up this nice looking Alpa Reflex. This particular model is called a Series E model and has a serial number which indicates it was made in 1948. In my research for the Alnea Model 7, I had read about these earlier Alpas with the combined waist level reflex finder and coupled rangefinder and was eager to give it a go.

Like the later Alpa, the earlier Reflex had a very high build quality. With Switzerland’s reputation as home to many quality watch makers, the Alpa cameras continue in this tradition. The main body is made of a lightweight metal alloy that isn’t aluminum. I know this because a magnet will stick to it, but at a weight of only 558 grams including the lens, the Alpa Reflex weighs less than most cameras of its era. The body has curved edges similar to a Leica, only thicker, and has a short top plate allowing for easy reach of the top plate controls without having to reposition your hand to change them.

Up top, the controls aren’t in exactly the same positions they’d be on later 20th century SLRs, but it is obvious enough what each does. Starting on the left is the rewind knob whcih can be lifted up to make it easier to remove the film cassette inside the film compartment. Next to it is the shutter speed dial with engraved markings from 1 to 1/1000 plus “P” which is Bulb mode. The engraved shutter speeds are colored black for speeds 25 through 1000, and red for speeds 1 through 1/10. The purpose of the red markings is that in order to use them, a lever on the front of the camera must be swung down to line up with a red dot. This front lever engages the slow speed escapement, similar to how many cameras where slow speeds are activated using a dial on the front of the camera. In order to change shutter speeds, you must first set the shutter by rotating the film advance knob, and then you can select a different shutter speed by pressing down on the shutter speed dial while rotating it in the direction of the arrow. Although the shutter speed dial is easy enough to use, its location is rather cramped between the rewind knob and viewfinder hood.

The center of the top plate has the viewfinder hood. The Alpa Reflex does not have an interchangeable viewfinder and there is no prism option. The waist level finder works as it does on pretty much every other SLR with this feature in which you lift up on the back edge of the film to reveal the ground glass within the hood. By sliding the finger grip on the back edge of the hood to the left, a rectangular magnifier swings into place for precision focus. Closing the magnifier can be done by sliding the finger grip to the right again.

Above and to the right of the viewfinder is a rectangular mirror up button. Pressing the button will manually flip up the mirror, blocking light from entering the viewfinder for as long as you hold it down. If you would like to keep the mirror up after taking your finger away, slide the button towards the front of the camera while pressing it down. The mirror up lever on the Alpa Reflex can be used to prevent body shake from the mirror flipping up at the moment of exposure, but it serves a second purpose, which is to allow for collapsible lenses to be attached to the camera. One of the most common lenses found on these cameras is the 5cm f/2.9 P. Angénieux Alepar/Alpar collapsible lens. You must raise the mirror and leave it in the raised position before attempting to collapse the lens, otherwise it will come in contact with the mirror and possibly damage it.

The base of the camera has a 1/4″ tripod socket on one side and a blank piece of metal on the opposite side. I am unsure of the purpose of this plate as there are no markings on it and there’s nothing directly above it on the inside of the film compartment. Perhaps this was intended for a future upgrade.

Around back, there’s little to see other than the two round eyepieces for the Alpa Reflex’s coupled rangefinder. The one on the left is for the split image rangefinder and the one on the right is for the direct viewfinder. The waist level hood on top of the camera does not have a provision for a sports finder, so for fast action shots, or those where it is impractical or difficult to see through the reflex finder, this is the preferred method for composing your shots. A compromise for having an SLR and a rangefinder on the same camera, is that unlike most coupled rangefinders, the two windows are very far apart, meaning there is a larger distance your eye has to travel to switch between the two. It is clear that the reflex finder was intended to be the primary way of using this camera, with the rangefinder as a backup option.

The rounded edges of the Alpa-Reflex are symmetrical with the only difference being the sliding lock for the film compartment on the camera’s right side. Slide the lock towards the top of the camera to remove the film door. The Alpa-Reflex lacks any type of strap lugs which means that the only way to carry the camera around your neck is by using the original leather case, or some kind of strap that connects to the tripod socket.

The entire back of the camera comes off when opening the film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a non-removable metal take up spool. The very earliest Alpa cameras had cassette to cassette transport, but this was changed in late 1944 to the design featured here. Although an early SLR, the film compartment looks and works like most SLRs to come over the next several decades. Inside the film door is a flat metal film pressure plate. The camera’s serial number is engraved into both the film door and inside the compartment where the film cassette goes. There are no light seals of any kind on the Alpa-Reflex which need to be replaced.

Looking down upon the P.Angeniex Alepar collapsible lens, there’s little to see. Like collapsible rangefinder lenses, you can extend the barrel by giving it a firm tug until it comes out the rest of the way. Unlike most rangefinder lenses however, there is no way to lock the lens into the “out” position. Once there, it just remains extended until you press it back in. In addition, you can rotate the lens barrel a full 360 degrees without any impediment. Near the front of the lens is a black ring for controlling the diaphragm with f/stops from f/2.9 to f/22. This ring turns smoothly, without click stops.

Up front, the front viewfinder lid has the name ALPA-REFLEX name along with MADE IN SWITZERLAND and PATENTS PENDING engraved. It is not usual for a camera maker to engrave the name of the country it is made, in such a prominent location, but I suspect they were proud of their Swiss heritage. Below and to the right of the lens mount is what looks like is a self-timer lever, but is actually the slow/fast speed lever I spoke of earlier. For all the black shutter speeds from 25 to 1000, this lever must be pointing to the right, however if you want to use the red shutter speeds from 1 to 1/10, this lever must be pointing down, towards a red dot on the base of the camera. The Alpa-Reflex does not have a self-timer.

To the right of the lens is a handle for controlling the focusing helix of the Alepar lens. From infinity, rotating the arm counterclockwise moves it along the distance scale to just under 1 meter. Distance markings are read from within a square frame that is inside of the arm. It is quite an elegant setup, but isn’t any better than a simple red or black mark like nearly every other lens maker uses.

The Alpa-Reflex uses a bayonet lens mount which is different from later Alpa cameras. Lenses for the Alpa-Reflex have a smaller throat diameter and a rangefinder coupling that is not present on other lenses. At the 3 o’clock position around the lens mount is the bayonet release button. Press this button and rotate the entire lens counterclockwise to dismount it. Reinstalling is the opposite of removal. A reminder is that if you are using a collapsible lens, the reflex mirror must be locked in the up position, otherwise the lens will make contact with the mirror.

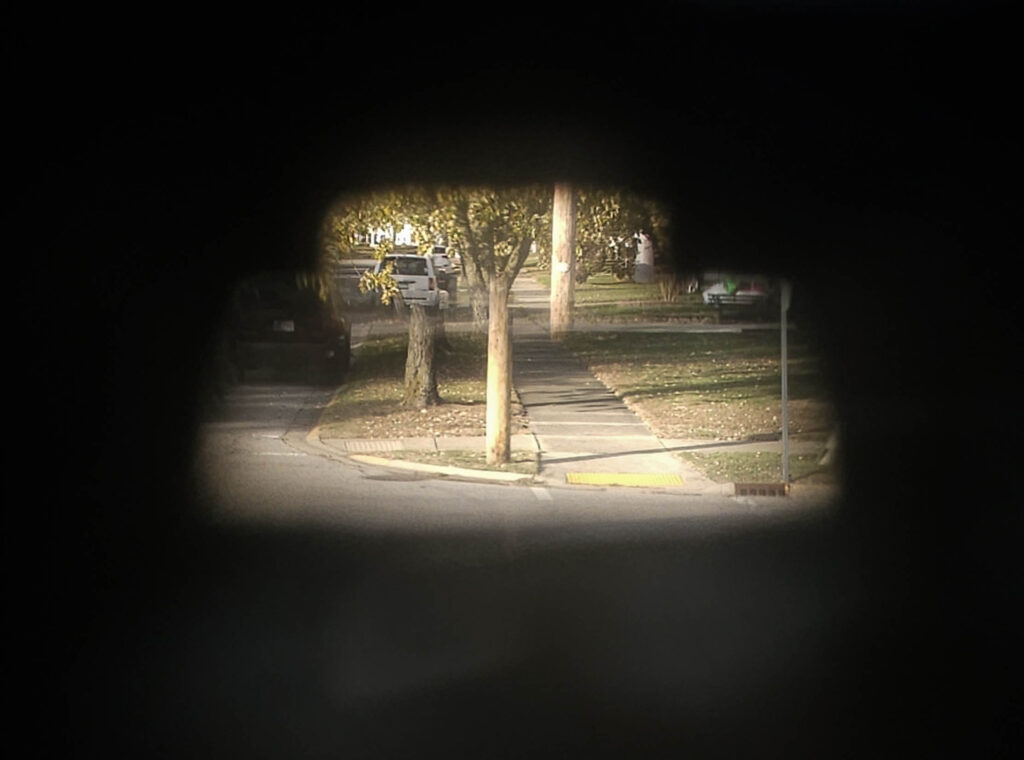

One of the coolest features of the Alpa Reflex is that it is both an SLR and a rangefinder in one. In 1944 when this camera was made, very few options existed for 35mm SLRs, and this one having a waist level finder which allowed the user to compose through the taking lens was a big deal, however, most people were still used to rangefinders, so that the camera could also do that meant that it had the best of both worlds. As is the case with all early SLRs, the look through the waist level finder is quite dim with heavy vignetting. Outdoors in bright light, the viewfinder is good enough to be used for most images, however indoors or in heavy shade, the image can become impossibly dark and that’s where you might turn your attention to the rangefinder. A black crosshair in the center helps to align the camera to a horizontal and vertical axis. No other focus aides or information about the camera is visible in the viewfinder. An optional flip up magnifying glass can be swung into position for critical focus using the waist level finder.

Utilizing a three window approach in which two windows comprise of an upper and lower half of the rangefinder and the third window being a complete separate viewfinder, you had the option of scale focusing through the large viewfinder, or measuring with a magnified split image in the other. The design of the rangefinder window is similar to that of cameras like the Argus C3 or the Kodak Medalist in which two separate images must be horizontally aligned. The view through the rangefinder is a magnified and doesn’t represent all that will be captured on film. When using the rangefinder, you must separately compose your image in the viewfinder window.

In my opinion, neither the rangefinder nor the reflex finders are better than the other. They both have their strengths and are useful in their own specific instances. That they work so well together was one of the main goals that Jacques Bolsky had when designing the first prototypes in 1939.

Even before rolling a single roll of film through the Alpa-Reflex, it was clear to me that this earlier model still had the good feel and build quality of the later Model 7 I had previously reviewed, but I was enjoying playing around with the viewfinders more. Despite being made over a decade earlier, would the Alpa-Reflex be more pleasurable to shoot? It certainly seemed that way, but there was only one way to find out. Keep reading…

My Results

Being reasonably certain the Alpa Reflex was in good working order, I did what anyone with a working Alpa did, and loaded it up with some film. What film you ask? Well if you’ve made it through a couple of my reviews, you’ll know that I most commonly test new cameras with bulk Kodak TMax 100, which is what I did here! I think TMax 100 is the perfect test film because I have a lot of it, but also that ASA 100 speed film matches perfectly with the shutter speeds in the range of 1/60 – 1/125 which on most cameras are the ones most likely to work properly. For first test rolls, don’t like to push the fastest and slowest speeds and I also prefer to use Sunny 16 in good daylight, which this film is ideally suited for.

Having already shot an Alpa SLR before and knowing the generally positive reputation of the lenses made for them, I had moderately high hopes for the modest P.Angenieux Alepar lens. The Alepar lens differs from similar looking Alpar lenses often found on these cameras in that the Alepar, with the ‘e’ in the name, have coated optics.

My first look at the images from the developed TMax 100 looked decent. I noticed that sharpness in the center was very good, but that there was an increase in smudgy details near the edges. Nothing that you shouldn’t expect from a 1940s triplet lens, but I was surprised at how soft the corners were considering the coated optics and reputation of Angenieux.

Minor nitpicks about edge softness aside, the images were certainly good enough and considering the Alepar was the base lens available for the system, it can be assumed that things only got better from here.

Using the Alpa-Reflex avoids one of the primary complaints I had about the Alpa Alnea Model 7 back in 2019 which was the 45 degree angled prism viewfinder. The Alpa-Reflex uses a fixed waist level finder which works like any other WLF you’ve used. The focusing screen is consistently bright with other early SLRs, but compared to later cameras is on the dark side. This likely shouldn’t cause an issue outdoors, or in good light, but if you needed to use the camera indoors or in heavy shade, I would definitely recommend using the rangefinder.

Another plus over the Model 7, is that if you choose to use the rangefinder, the orientation of the two windows is horizontal like pretty much every other rangefinder ever made. The later rangefinder equipped Alpa SLRs famously oriented the two rangefinder windows above and below each other which means that focusing the lens moves the combined image vertically, which is quite unfamiliar and further slows you down. Considering that the later Model 4-8 Alpa SLRs were considered upgrades to the original Alpa-Reflex, the viewfinders were a bit of a step back for me.

By far, my favorite attribute of the Alpa-Reflex is its compact size. Lacking a pentaprism, the height and overall size of the body is only marginally larger than a screw mount Leica. Placed side by side next to a Nikon EM, which is one of the most compact full frame SLRs ever made, the Alpa-Reflex sits a good half inch lower than the tip of the Nikon and barely half an inch wider. This allows for easy handling and better portability. Combine that with the convenience of a waist level finder as opposed to the unusual angled prism on later Alpas, and for me, the Alpa-Reflex is the better camera to use.

Nitpicks do exist, as you might expect from any 1940s SLR. I found the location of the shutter release uncomfortably close to the side of the viewfinder hood, the shutter speed dial is unnecessarily cramped on the left side of the camera and the confusing red/black fast and slow speed arrangements aren’t ideal. I think that had a more familiar ‘fast speeds on the top and slow speeds on a dial up front’ arrangement would have made more sense. For those who prefer the rangefinder over the reflex finger, the two eyepieces on the back of the camera are farther apart than any other I’ve seen, slowing down the process of focusing and composing. The lack of strap lugs means that you have to rely on a leather case to carry around the camera which is not ideal. One last nitpick is that the knurled edges of the mirror up lever immediately in front of the shutter release are asking to catch the camera on clothing, or scratch your finger as it rubs past things. A normal shaped button would have worked just as well and not been a snag-hazard.

Switzerland was known for many things, but outside of Alpa, making cameras wasn’t one of them. That this company went out on their own and released a pioneering new 35mm SLR years before many other companies and still managed to get as many things right as they did is a testament to their creativity and manufacturing prowess. The Alpa-Reflex is a very good camera, that despite some questionable ergonomics decisions, can still be a capable camera today. I doubt many people reading this will run right out and buy a 75 year old Swiss SLR and go on a photo walk across Europe, but for a few rolls, they are me preferred Alpa SLR.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/alpa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alpa-Reflex_Camera

https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/pp/alpareflex.htm

https://www.photrio.com/forum/threads/alpa-prisma-reflex-on-test-roll.198784/

https://web.archive.org/web/20161207191236/http://www.alpareflex.com/Cameras/AlpaReflexOriginal.htm (Archived)