This is the Argus C-series. First released in 1938 as the Argus Model C, the C-series includes the best selling American camera ever made, the Argus C3. Over 2.2 million were produced over the course of 28 years, the C-series saw many subtle variations and incremental improvements, but generally retained the same brick-like shape and pre-war feature set until the very last cameras came off the assembly line in 1966. The reason for it’s success was it’s unique looks, quality optics, capable feature set, and affordable price. The C-series had an interchangeable lens mount, and had a variety of German made auxiliary lenses available for it. It was used by amateurs, professionals, students, the military, and countless other people in nearly every profession.

This is the Argus C-series. First released in 1938 as the Argus Model C, the C-series includes the best selling American camera ever made, the Argus C3. Over 2.2 million were produced over the course of 28 years, the C-series saw many subtle variations and incremental improvements, but generally retained the same brick-like shape and pre-war feature set until the very last cameras came off the assembly line in 1966. The reason for it’s success was it’s unique looks, quality optics, capable feature set, and affordable price. The C-series had an interchangeable lens mount, and had a variety of German made auxiliary lenses available for it. It was used by amateurs, professionals, students, the military, and countless other people in nearly every profession.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 Argus Cintar coated and uncoated 3-elements

Lens Mount: Argus Screw Mount

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Scale Focus and Split Image Coupled and Uncoupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Argus/Ilex Behind the Lens Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/5 – 1/300 seconds (varies, some models start at 1/25)

Exposure Meter: Clip On Selenium Cell

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Argus Flashgun Mount, (all have FP sync at 1/25, later models X-sync at all speeds)

Weight: 672 grams (C), 766 grams (Prewar C3), 756 (Standard C3), 800 (Match-Matic w/ Meter)

Manual (C2): http://www.cameramanuals.org/argus/argus_c-2.pdf

Manual (ColorMatic): http://www.cameramanuals.org/argus/argus_c-3.pdf

Manual (Match-Matic): http://www.cameramanuals.org/argus/argus_match-matic.pdf

How these ratings work |

The blah blah blah | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance, the most famous American camera ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 13.6 | ||||||

Prologue

Back on December 12, 2014, I posted my first ever camera review on this site, for the Argus C3 Match-Matic. The idea to write about an old camera was just something I thought up on a whim and put together that review with my thoughts, and some sample pics I got from that camera. Never in a million years, would I have imagined that nearly five years later, my site would have grown into what it was. Over the years, I’ve refreshed a few posts to bring them up to my current formatting standards, but with this review, I’m leaving that original post as it was when I first published it, and creating an all new article covering the entire Argus C-series. I hope you enjoy it.

History

Of all the American companies who produced cameras in the 20th century, Argus was second only to Kodak in terms of sales and brand recognition. If you consider that despite their tremendous success, Kodak was a film first company, whereas Argus largely stayed within the camera making business, so you could say that Argus was the most successful American camera company of all time.

Based in Ann Arbor, MI, Argus was founded in 1931 as the International Radio Corporation by a group of 10 investors including Ann Arbor mayor, William Brown and businessman Charles Verschoor. The new company was located in the former headquarters of the Argus Furniture Company, located at 405 Fourth Street.

Back then, IRC made a variety of different radios, many of which had pioneering designs largely using Bakelite plastic, a relatively new material in the construction of radios and other electronic appliances. IRC’s products included the Kadette which was the first mass produced AC/DC radio. Bakelite was a very flexible product that could be made in a variety of colors, including a wood grain which gave it a look of a much more expensive radio. It sold extremely well and allowed IRC to release other Kadette products like the Kadette Jr, which was the world’s first pocket radio, and the Kadette Clockette which was one of the first clock radios.

In the first half of the 1930s, IRC’s radio business was so successful in that it was the only company in Ann Arbor that was able to pay dividends to it’s share holders during the Great Depression. Nearby Detroit was heavily hit by the recession, so in the entire state of Michigan, IRC was one of the few financial bright spots.

By the mid 30s as the depression dragged on, other competing radio manufacturers were able to make inexpensive radios that ate into IRC’s profits, so the company needed to find a way to diversify it’s product offerings. On a trip to Germany, Charles Verschoor looked at a Leica camera and thought that with his expertise at making inexpensive items using Bakelite, that he could do for the camera industry, what he did for the radio industry.

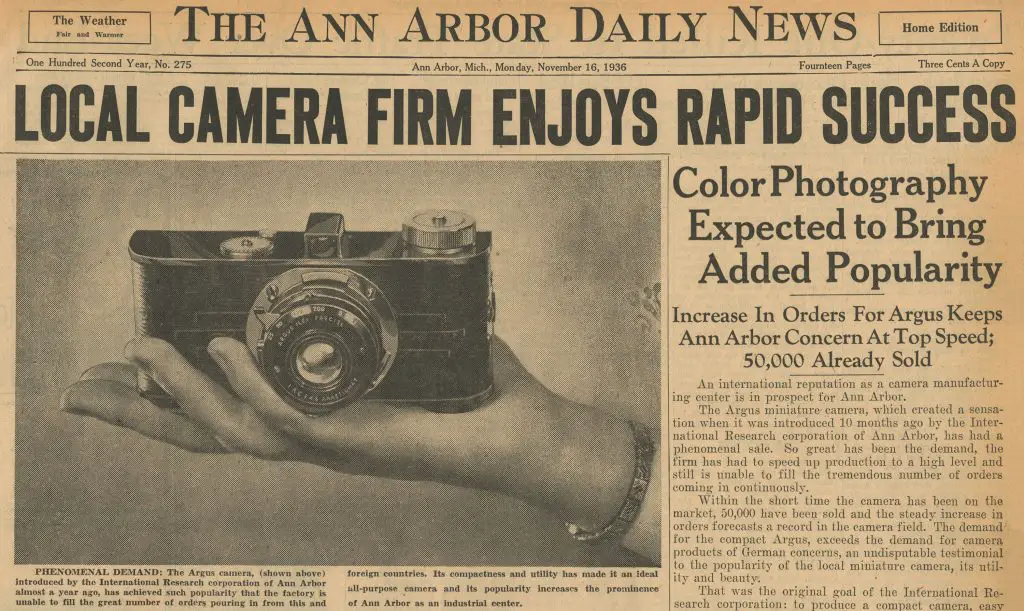

IRC would release the Argus Model A camera in 1936 to immediate success. Like it’s radio division, the Argus Model A was an inexpensive Bakelite body camera that brought photography into a price range that didn’t have a lot of competition. The price of the Argus A then was $10 (some sites say $12.50) which meant it could be afforded by the average lower to middle class family.

The design for the Argus Model A is most often credited to a Belgian designer, professor, and engineer named Gustave Fassin. Fassin was a bit of a freelance of sorts in the 1930s as a part time professor and designer for Bausch & Lomb, Kodak, Argus, and perhaps other companies. I found no evidence that suggests he was a permanent employee of IRC, so perhaps he was paid as an independent contractor to come up with the design.

The Argus A was the very first American made camera to use Kodak’s new 135 format 35mm film cassette. Even though Kodak had already been selling the Kodak Retina for 2 years prior to the Model A’s introduction, the Retina was designed and built by Kodak AG Stuttgart, Kodak’s German subsidiary.

It sold very well, so well in fact, that IRC decided to stop radio production altogether and focus entirely on producing cameras. In 1938, due to the success of it’s cameras, IRC officially became known as the Argus Corporation and sold off it’s radio division to an entirely new company.

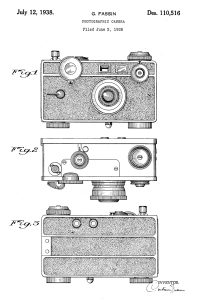

Sensing an even greater need to offer more competitive features in a camera at a low price point, later that year, Argus once again tapped Gustave Fassin for the design of their next camera. Fassin filed design patent 110,516 on June 2, 1938 for what would become the Argus C.

Although Fassin designed the camera, the shutter was built by Theodore M. Brueck, while working for the Ilex Optical Company of Rochester, New York. Patent 2,176,621 was filed with the US Patent Office under Brueck’s name assigned to Ilex on August 1, 1938 around the same time as the release of the Argus C. This patent clearly shows the front of an Argus C, but has no mention of the company or the Argus camera by name. Instead, the text within the patent mentions the need for a very shallow and compact shutter that can be attached to “a camera of the type to which my invention is applied”.

Although clearly showing an Argus front plate, there are some notable differences between the shutter showed in the patent and what actually appeared in the camera. For one, the shutter speed dial is located on the front plate of the camera, to the left of the lens mount, with speeds 1/2 – 1/300 plus B and T on a single dial. This of course is not how the shutter speed dial ever looked. There is some kind of sliding switch above the dial which the documentation describes as a “setting pin” but it’s function is not clear to me.

Another deviation between the drawing in the patent and the real Argus shutter is that the patent shutter has five blades whereas all Argus shutters I’ve ever seen have only three. The patent shutter also looks far more complex than any I’ve seen in an Argus suggesting this shutter isn’t at all the same as the one in the final camera. Since the patent was filed in the same year as the camera went on sale, perhaps the patent shutter was a proposed version for a later Argus camera, but never developed, or maybe even this shutter is not at all related to the ones found in the Argus C-series, and maybe Brueck just liked the Argus design and used their front plate design as a template for a completely unrelated shutter.

Is this a glimpse of a future Argus prototype or an early iteration of a shutter that was later simplified? We’ll likely never know the answer, or what role this patent shutter plays in the final version, but its a fun look at a possible alternate version of what might have been.

Argus’s new camera shared almost nothing with the earlier Model A. Featuring a distinct brick-shaped Bakelite body with polished metal front and back panels, an interchangeable lens mount, and an uncoupled split image rangefinder, the Argus C was quite a step up from the Model A.

Fun Fact: There actually was an Argus B produced in 1937, but it was just a variant of the Model A with a German Prontor II shutter and Argus 50mm f/2.9 lens. This model was produced for a very short time and only a couple hundred are thought to exist.

Perhaps the best feature of the Argus C was it’s price. Argus believed that the average American working family should be able afford a high quality and competent 35mm camera, so they priced the C at $25, which was the average weekly salary of a typical American family at the time. This price compares to $454 today which before taxes, adjusted for a 52 week year, compares to someone making $31,477 in 2019.

The Argus C saw several updates very soon after it’s release, the first being a redesign of the slow speed governor on the shutter. It was found that the original model’s “Fast/Slow” shutter was unreliable, and it was simplified to have a single shutter speed dial with speeds from 5 – 300 on it. Both Arguses with and without this hi/low speed switch are officially called the Argus C.

The next change was the addition of a coupling wheel in between the lens mount and the rangefinder wheel. Although a seemingly minor feature, it meant that adjustments to the focus distance on the lens automatically moved the rangefinder whereas prior, when a distance was measured on the uncoupled rangefinder, the photographer would have to separately rotate the lens. Models with the coupling wheel were called the Argus C2 and the price remained $25.

The third change was an upgrade to the shutter for flash synchronization and adding two small holes on the camera’s right side, which connect to a proprietary Argus flash gun. When using flashbulbs with this flash gun, the camera was synchronized at all speeds. Models with the flash synchronization were called the Argus C3.

The C and C2 both debuted in 1938, with the C3 in early 1939. The original model was only offered one year, the C2 was produced through 1942, and the C3 was produced both before and after the war.

The new C-series was an immediate success and many were sold, but Argus was losing money as fast as they could make it. Company president, Charles Verschoor was a visionary businessman and keen salesman, but lacked financial prowess. A lack of proficient bookkeeping, overgenerous stock dividends, and elaborate corporate spending, caused the company to have a net loss, despite great sales. This resulted in Verschoor’s resignation from Argus in 1938.

Under new management led by businessman Robert D. Howse, Argus reinstated radio production and quickly turned to military contracts for the US war effort in Europe. In the early 1940s, Argus became profitable again producing binoculars, gun sights, radio power supplies, remote controls, and other products for the United States and it’s allies. They also increased capacity for the Argus C3 35mm rangefinder and started producing a medium format twin lens reflex camera called the Argoflex.

By 1942, business was very good for Argus, with profits up to $4.8 million from a net loss in 1938. After the war, Argus sought to remain dominant in it’s consumer camera divisions but planned to continue it’s work with American and foreign militaries, using it’s experience to continue to develop optical and radio products. This was rather unique in the optics industry as most companies who turned to military production during the war, ceased all government contracts afterwards, but not Argus.

Argus was so invested in the war effort, in 1945 they produced a propaganda video to showcase the company’s efforts in the American war effort. The video is shown below, and was digitized by the Ann Arbor District Library.

The aftermath of World War II caused a disruption in supply of cameras and other optical equipment from Germany which caused many American companies to take up the challenge of building all new models to compete for the American photographer’s buying dollar. Established companies like Kodak and ANSCO released new cameras in the late 1940s, as did some newcomers like Clarus and Vokar, but the Argus C3 remained a best seller.

During the 1940s and 50s, working for Argus was a big deal. Thousands of employees from the Ann Arbor area worked for the company, receiving generous profit sharing incentives. The company had a newsletter called “Argus Eyes” that helped connect each employee with the direction of the company. Argus sponsored many athletic events, even having it’s own employee basketball and bowling teams. The company had elaborate Christmas parties and other social gatherings, often sharing news of marriages and child births in it’s company newsletter. It was a great honor to work for Argus during this time.

In January 1951, Modern Photography magazine ran a 7 page article on the Argus C3 which was generally positive, spending a lot of time on using the camera and it’s accessories. The article cautions you not to allow your finger to get in the way of the cocking lever when pressing the shutter release, and also gives some negative comments on the bulkiness of the camera’s case and the position of the aperture ring.

When camera production resumed after the war, the Argus C3 immediately went back on sale in late 1945. Initially, the very first post war cameras were identical to the pre-war versions, but by July 1946, cameras were produced with coated Cintar lenses and other minor cosmetic variations. The price had gone up too. The November 1949 issue of US Camera shows an ad for the C3 with case and flash unit for $78.08 after tax, quite a lot higher than the original $25 price tag of the first model. Of course the higher price wasn’t due to greed, rather inflation and a disruption of supplies were likely contributors.

The Argus C3 was tremendously successful in each year after the war through the end of the 1950s when sales started to decline. Although Argus never kept any detailed production numbers, we can reasonably estimate based on known serial number ranges that average annual sales during this time was somewhere around 150,000 cameras a year which is pretty incredible considering how long it was produced.

By 1958, Argus was struggling to stay profitable and was on the verge of bankruptcy. Although they had released a few other, more advanced cameras such as the C33 and C4 series, people kept buying C3s, and Argus wanted to freshen up the design to make the camera more relevant, so that year, they released two new models, one called the C3 Standard, and the other the C3 Match-Matic. Both cameras got a redesigned Cintar lens with a more attractive and larger barrel, an accessory shoe on the top plate of the camera, a new shutter release, and came with an Argus selenium exposure meter for the accessory shoe.

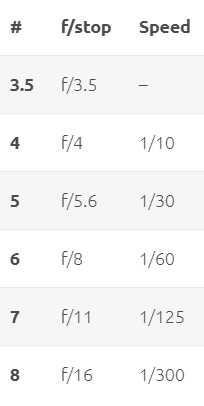

The Match-Matic came with a unique black and tan body covering, and simplified the exposure system by eliminating any reference to shutter speeds and f/stops, replacing them with numbers on the shutter dial and lens that you were to add together to get an EV (exposure value). The included meter indicated it’s light readings using these EV numbers, so if for example, the meter returned a reading of 12, any combination of numbers on the shutter dial and lens that added up to 12, would result in a properly exposed image.

In 1959, Argus would be bought out by Sylvania Electric Products Inc who themselves had merged with General Telephone to form General Telephone and Electronics (GTE). Under new leadership Sylvania started to outsource production of new Argus cameras to other German and Japanese companies such as Certo, Iloca, Petri, and Mamiya. The Argus V-100 seen to the left was one such camera, which is just a rebadged Iloca Rapid IIL.

By the mid 1960s, the Argus Match-Matic and Standard were the only Argus cameras still manufactured in the United States, and in 1966, after a run of 28 years, production came to an end.

By the late 1960s, Argus would close up shop in Ann Arbor and relocate to South Carolina. The Argus name would continue to linger about for the next several decades as a badge applied to cheap Instamatic and pocket cameras. By the 2000s, it was even applied to some Chinese made digital cameras too, but nothing remotely that ever came close to the C3.

Today, the Argus C3 remains one of the most iconic cameras ever produced. Not only is it’s appearance unmistakable, but it is a popular prop used in motion pictures which portray photography in the early mid 20th century.

Argus C-series cameras are highly collectible, both intentionally, and unintentionally. Argus C3s often show up for prices so incredibly low, collectors who aren’t even interested in them somehow find them in their own collections. I have personally acquired a few in lots of other cameras where I wanted something else in the lot and the C3 just came along for the ride.

That doesn’t mean that they are not deserving of their place. The Argus C3 and it’s family played an extremely important role in the history of cameras, and one that is deserving of recognition. They’re harder to find in other areas of the world besides the United States, but if you get a chance to pick one up, I strongly recommend giving one a shot.

Repairs

The Argus C3 was not only a popular camera for it’s capabilities as a camera, but also due to it’s reliability and ruggedness. Of course no camera is totally immune from dirt, grime, or the perils of time, but even when Argus C3s do experience problems, they’re usually pretty easy to fix even for someone with no experience repairing cameras, making them a popular choice for someone wanting to learn how to repair cameras.

As with any camera repair, having good tools, a clean and brightly lit working environment, and patience are all prerequisites to a successful repair. If you have access to more than one Argus, it might be a good idea to practice on the “lesser” one as a practice camera for the “better” one. The first camera I ever took apart was an Argus, and while I would never consider myself a master camera technician, I don’t know that I would have had the courage to do as much as I have, had it not been for the Argus.

Below, I will show you the three most common issues that Argus C3s and all the variants are likely to encounter, a stuck or sluggish shutter, dirty viewfinder and rangefinder windows, and a misaligned rangefinder. Each of these three repairs can be done by a novice with basic tools, and about an hour of your time. For these images I am using an early post-war Argus C3. I will make a note if there is a difference between this one and other Arguses I’ve seen.

Cleaning the Viewfinder and Rangefinder Windows

This is a job that nearly every single Argus C-series camera I’ve ever encountered has needed. Most old cameras can develop dirty or hazy viewfinders, and the Argus are no different. Most cameras require the removal of the camera’s top plates to access the viewfinder glass, which itself requires removal of rapid wind levers, accessory shoes, rewind knobs, and other parts. With the Argus, you only need to remove two circular retaining rings and two small pieces of glass, and use a wet Q-tip with some glass cleaner to clean it out.

The only tool you’ll need for this job is a small 1.0 mm precision screwdriver. I use Wiha screw drivers that I purchased from Amazon and they’ve worked wonders on many cameras I’ve repaired.

First, open the rear of the camera so you can see into the film compartment. Look inside each of the two windows for the viewfinder and rangefinder, and you’ll see a small black circular retaining ring holding the glass lens in place.

All you’ll need to do is use your screw driver and gently pry this retaining ring out. It is only in there with friction, so it will come out with a small amount of force, just be careful not to damage the glass lens. These also have a tendency to go flying, so its a good idea to lay a paper towel or something else above the camera to deflect this retaining ring in case it flies out of the camera once you get it out.

All you’ll need to do is use your screw driver and gently pry this retaining ring out. It is only in there with friction, so it will come out with a small amount of force, just be careful not to damage the glass lens. These also have a tendency to go flying, so its a good idea to lay a paper towel or something else above the camera to deflect this retaining ring in case it flies out of the camera once you get it out.

In later Arguses, once you get the glass element out of the rangefinder side, there will be a black plastic tube that will also fall out. Just set this aside and don’t forget to put it back in when reassembling things.

With each of the retaining rings out, the glass lenses just fall out of the camera and you can clean them with simple glass cleaner. Using a Q-tip, you can clean the inside of the front viewfinder window and another glass piece in front of the rangefinder. You won’t be able to clean the rangefinder mirrors this way, so if they’re cloudy, you’ll need to remove the rangefinder to give that a good cleaning, which I discuss in the next section.

When putting the viewfinder and rangefinder back together, the two pieces of glass are not the same. On earlier Arguses, the one that goes in the rangefinder is flat on both sides and it does not matter how it goes in, but on later models one side of the glass has a concave shape that must face inward to the camera. The viewfinder lens on all models, is convex on one side and flat on the other. The convex side must face inward to the camera with the flat surface facing the back of the camera.

When putting the viewfinder and rangefinder back together, the two pieces of glass are not the same. On earlier Arguses, the one that goes in the rangefinder is flat on both sides and it does not matter how it goes in, but on later models one side of the glass has a concave shape that must face inward to the camera. The viewfinder lens on all models, is convex on one side and flat on the other. The convex side must face inward to the camera with the flat surface facing the back of the camera.

Adjusting/Cleaning the Rangefinder

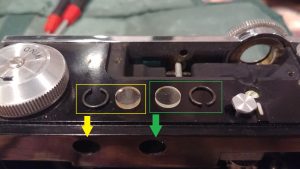

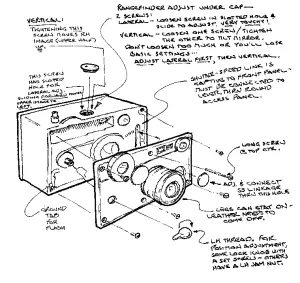

If all you need to do is adjust the rangefinder, there is a circular access port on the top of the camera that has two divots for a spanner wrench. Remove the circular cover indicated by the LIGHT BLUE arrow in the following image, and you’ll have access to an adjustment screw for the horizontal access of the rangefinder.

In some cases, you may need to give the rangefinder a thorough cleaning, or perhaps there is a problem with one of the mirrors that has become unglued from it’s mount, or perhaps it has desilvered and needs to be replaced. To do this, you need to remove the entire rangefinder, which is incredibly easy to do. Like cleaning the viewfinders, there is no top plate of the camera to remove in order to access the rangefinder. The entire rangefinder assembly can be removed through the top of the camera.

In some cases, you may need to give the rangefinder a thorough cleaning, or perhaps there is a problem with one of the mirrors that has become unglued from it’s mount, or perhaps it has desilvered and needs to be replaced. To do this, you need to remove the entire rangefinder, which is incredibly easy to do. Like cleaning the viewfinders, there is no top plate of the camera to remove in order to access the rangefinder. The entire rangefinder assembly can be removed through the top of the camera.

On earlier Arguses there are a total of three screws indicated by BROWN arrows in the image to the right, which are holding the rangefinder into the camera, two of them are simply screwed in the top plate, and the third is through the center of the exposure counter. On later Arguses, there is a fourth screw behind the exposure counter disc. You’ll need to remove that first before you can remove the fourth screw. A word of caution is when you unscrew the exposure counter, you’ll feel a gear shaft drop inside of the film compartment. Don’t worry, this is normal, you’ll address this later when reassembling. Some models will have a spring around the exposure counter shaft that you’ll need to set aside as well.

With all of the screws out, the rangefinder simply lifts off. There is a protruding “finger” from the rangefinder that goes into the circular compartment behind the rangefinder adjustment wheel that sometimes gets caught, but just be careful and it will come out. I’ve found that it is easier to get the rangefinder out of earlier Arguses. Later models have a slightly different design to the rangefinder which makes it a little trickier to get out. Don’t worry though, it will still come out.

With all of the screws out, the rangefinder simply lifts off. There is a protruding “finger” from the rangefinder that goes into the circular compartment behind the rangefinder adjustment wheel that sometimes gets caught, but just be careful and it will come out. I’ve found that it is easier to get the rangefinder out of earlier Arguses. Later models have a slightly different design to the rangefinder which makes it a little trickier to get out. Don’t worry though, it will still come out.

Now that the rangefinder is out, you can give both mirrors a good cleaning. If they have become unglued, simply reglue them into position. I have used rubber cement for this with great results. The rubber cement won’t damage the mirror, and is soft enough to withstand vibrations without having the mirror fall again. You should also be able to reach the inside of the tinted rangefinder window on the front plate of the camera to give it a good cleaning.

Now that the rangefinder is out, you can give both mirrors a good cleaning. If they have become unglued, simply reglue them into position. I have used rubber cement for this with great results. The rubber cement won’t damage the mirror, and is soft enough to withstand vibrations without having the mirror fall again. You should also be able to reach the inside of the tinted rangefinder window on the front plate of the camera to give it a good cleaning.

Once you’re done with the rangefinder, you put it back together the opposite of how you took it apart. Be careful of that finger that needs to go behind the rangefinder adjustment wheel. You may need to use a small screwdriver to hold the finger back while sliding it into position.

With the rangefinder back where it belongs, screw in the first two screws holding it into position and then for the one that goes through the exposure counter, you’ll need to open the film compartment of the camera. Near the top of the film sprocket shaft, you’ll see two gears. One of them is permanently attached to the sprocket shaft, the other connects to the exposure counter, but has fallen out of position.

Look at the image to the left and you can see the bottom gear, indicated by a PINK arrow, is not aligned. This is wrong. They must be aligned with each other, or else you won’t be able to screw the exposure counter back in.

Look at the image to the left and you can see the bottom gear, indicated by a PINK arrow, is not aligned. This is wrong. They must be aligned with each other, or else you won’t be able to screw the exposure counter back in.

You’ll need a screwdriver (Rick Oleson uses a Popsicle stick for this) and possibly a second person to put upward pressure on that second gear, so it stays aligned with the first gear, and then you’ll be able to screw the exposure counter screw back in. The image to the right shows the same gear indicated by a PINK arrow, in it’s correct location.

You’ll need a screwdriver (Rick Oleson uses a Popsicle stick for this) and possibly a second person to put upward pressure on that second gear, so it stays aligned with the first gear, and then you’ll be able to screw the exposure counter screw back in. The image to the right shows the same gear indicated by a PINK arrow, in it’s correct location.

This likely sounds much harder than it really is. Basically, with the second gear too low in the film compartment, the threads for the screw on the exposure counter won’t reach it, and you need to hold it in the upper position.

Cleaning the Shutter

The Argus C-series uses a fairly stout leaf shutter that is more tolerant of dirt and debris over time that would prevent it to from working, but any shutter has it’s limits, and many Argus cameras are found with an inaccurate shutter. I’ve never actually seen an Argus with a shutter that wouldn’t fire at all, usually the problem is that the shutter fires either too fast or too slow for the chosen speed and just needs to be cleaned.

It’s normally a pretty controversial by professional camera repair technicians to clean a camera shutter using naphtha oil or lighter fluid, I know this was a camera served by the US military on battlefields using whatever solvents they could find, so in this case, I feel no hesitation in recommending a lighter fluid flush on an Argus C-series shutter. You can use any brand name of lighter fluid such as Ronsonol or Zippo, or you can buy Naphtha Oil in bulk from your hardware store. A local chain where I live sells half gallon metal cans for about $7 each.

Gaining access to the Argus shutter is as simple as removing the entire front plate off the camera. There are 6 screws that hold the plate on, but they’re all behind the body covering of the camera. On older Arguses, the body covering can usually be peeled back with a small screwdriver to gain access to the screws without damaging it. Of the six screws, each of the five indicated by RED arrows are the same length with the last one, indicated by a YELLOW arrow is considerably longer.

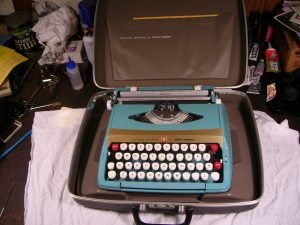

I’ve noticed later cameras, like the Match-Matic models use a paper thin material that tears very easily and won’t likely be removed without being destroyed. This is why the Match-Matic in my collection is blue and black. Since I destroyed the body covering, and no camera leather places offered a tan skin that matched the original color, I decided to just do something completely different.

I’ve noticed later cameras, like the Match-Matic models use a paper thin material that tears very easily and won’t likely be removed without being destroyed. This is why the Match-Matic in my collection is blue and black. Since I destroyed the body covering, and no camera leather places offered a tan skin that matched the original color, I decided to just do something completely different.

Before removing the front plate, you’ll need to remove the cocking lever. This lever is screwed on, but the threads are reverse thread, so lefty tighty, righty loosey. With the lever off, you’ll see a hex nut indicated by the BLUE arrow in the image to the left, behind it, remove this also.

Before removing the front plate, you’ll need to remove the cocking lever. This lever is screwed on, but the threads are reverse thread, so lefty tighty, righty loosey. With the lever off, you’ll see a hex nut indicated by the BLUE arrow in the image to the left, behind it, remove this also.

Assuming you’ve either peeled back the body covering or removed it entirely, remove all 6 screws, set them aside, and the top will lift off. The screw in the top center beneath the rangefinder window is considerably longer than the other 5, so make sure you keep track of that when putting the camera back together.

With the cover off, you can see a couple of different things. The first is the slow speed governor for the shutter indicated by a GREEN arrow in the image to the right. The Argus shutter is actually a single speed leaf shutter. It is able to vary it’s speeds by the use of this governor. Without a delay, the shutter fires at 1/300. With a tiny bit of delay, 1/100, with even more delay, the speeds continue to slow down. If the shutter on your camera is sluggish on the slow speeds, you’ll need to flush this out with lighter fluid or naphtha oil. Be generous with you, you won’t hurt anything. Get this governor clean and you’ll have more accurate speeds.

With the cover off, you can see a couple of different things. The first is the slow speed governor for the shutter indicated by a GREEN arrow in the image to the right. The Argus shutter is actually a single speed leaf shutter. It is able to vary it’s speeds by the use of this governor. Without a delay, the shutter fires at 1/300. With a tiny bit of delay, 1/100, with even more delay, the speeds continue to slow down. If the shutter on your camera is sluggish on the slow speeds, you’ll need to flush this out with lighter fluid or naphtha oil. Be generous with you, you won’t hurt anything. Get this governor clean and you’ll have more accurate speeds.

Next, is a brass ring behind the focus wheel on the front of the camera. This brass ring pushes on a finger connected to the rangefinder which allows you to see what focus distance the camera is set to. This ring can get dirty and sticky, so I recommend cleaning it thoroughly with some Q-tips.

Finally, on the back of the front cover, there should be a metal bar with a pin on the end which sadly, is missing in the previous image. I did not notice it wasn’t there when shooting these images, and by the time I noticed, the camera was already back together. What this bar does, is connect the shutter speed dial to the rotating disc, indicated by a PURPLE arrow, which rotates, pushing a long metal rod that activates the governor, depending on the position of the shutter speed dial. If this bar is out of position, bent, or missing like on the image above, the shutter will only fire at one speed. Make sure this piece is connected correctly and is clean before putting the camera back together.

The shutter blades themselves might also be dirty and in need of a cleaning. Using a naphtha soaked Q-tip, clean the blades as best as you can, and also clean the three pivot points indicated by ORANGE arrows in the image to the left. A very small drop of white lithium or synthetic grease on these pivot points can also help improve things.

The shutter blades themselves might also be dirty and in need of a cleaning. Using a naphtha soaked Q-tip, clean the blades as best as you can, and also clean the three pivot points indicated by ORANGE arrows in the image to the left. A very small drop of white lithium or synthetic grease on these pivot points can also help improve things.

That’s all there is to cleaning the shutter on the Argus. If it is physically damaged, or parts are missing, the camera is likely beyond repair and it would likely be more cost effective just to locate another Argus at that point.

With the cover still off, you have easy access to the rangefinder and front viewfinder windows. If you have not done the previous steps of cleaning the rangefinder and viewfinder windows, here is another chance to do it.

Make sure everything is in it’s correct position, put the front plate back on, and put the screws back in making sure to put the long one in the correct location and you’re all done.

Other Repair Information

If you’d like more information about repairing Argus C-series cameras, the Argus Collectors Group has a couple of different guides on their site with information on cleaning and repairing the C3. Those guides are here, here, and here.

Rick Oleson also has several drawings of the Argus in various stages of disassembly showing how things like the shutter works, how the lens is assembled, and how to repair the film counter disc.

Aly’s Vintage Camera Alley has a video showing how to give an external wipe down and cleaning of the viewfinders in an Argus Match-Matic.

Finally, Mektar Polypan has an excellent guide on his site with pictures showing how to completely service an Argus C3 and the Cintar lens.

Identifying the Argus C-Series

Argus produced the C-series from 1938 through 1966, but there were many changes along the way. Some received updates to the model number, others were just minor cosmetic changes that largely went unnoticed. I do not have in my collection every single variant of the C-series, but I have most of them so what follows is my attempt at a comprehensive identification guide.

Note: A large amount of the information below comes from the Argus Camera Information Reference Site by Phillip G. Sterritt. This is a wonderful resource that I strongly recommend you take some time to read if you’d like more information than what I have presented below. The range of serial numbers he lists for each year comes from a variety of sources, but most significantly a survey he did of readers submitting information about their cameras and should only be considered an estimate.

C (1938)

The original Argus C was produced only in 1938. It was the most basic camera and sold for $25 upon it’s release. The most distinct feature of the C is the lack of the coupling gear between the lens and rangefinder window. This means that the rangefinder and lens could be turned independently of each other. In order to take a reading, you’d need to look through the rangefinder window and get your images to line up, then look at the rangefinder wheel and see what distance is indicated, and then turn the lens to match the same distance and take your photo.

As you might imagine, this was rather cumbersome and was quickly resolved with the release of the C2 which added a coupling gear that appeared on all later models.

Fun Fact: Because the lens on the original C had to be focused separately from the rangefinder, it is the only Argus 50mm lens with it’s own focusing scale. All later Cintars only indicated distance using the rangefinder wheel.

There are two variations of the original C, the earlier ones with a “Fast” and “Slow” speed switch which alternated the available shutter speeds between two ranges of speeds. The shutter speed dial would have two numbers at each position, the slower for when the switch is in the Slow position and the other for the Fast position. Phillip Sterritt has some information including two drawings by collector Bill Powell that shows how the original C shutter worked and how it compares to the later design.

The earlier design must have been either problematic or too expensive to produce as Argus quickly replaced it with a simpler system in which the shutter speed dial has ten speeds from 5 to 300 on it. It is estimated that less than 1800 cameras were produced with this switch, with the rest having the single 10 speed shutter dial.

C2 (1938 – 1942)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/argus/argus_c-2.pdf

Shortly after the Argus C’s release, an updated model called the C2 debuted which added a coupling gear in between the lens mount and rangefinder wheel. This allowed for simultaneous adjustment of the focus distance while seeing distance changes in the rangefinder. By 1938, coupled rangefinders had become the norm in more expensive German cameras like the Leica II and Kodak Retina II, so to have this feature in an inexpensive American camera was a big deal.

Even more amazing is that the price of the C2 remained at $25 meaning the upgrade was essentially free. I found no information about this, but I wonder if Argus offered an upgrade or trade-in program to people who had already bought the original model, and wanted the coupled model since they sold for the same price.

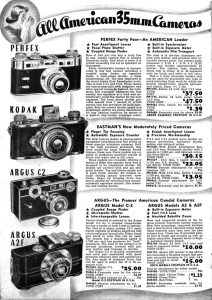

The ad to the right comes from the Lafayette Camera Corporation’s 1939 catalog and shows the Argus C2 selling for $25, which was lower than the non-rangefinder Kodak 35, and the top of the line American rangefinder, the Perfex Forty-Four.

The C2 saw a few minor cosmetic changes during it’s five year production run such as:

- Shutter release button changed shape in late 1939

- Lenses began being branded as Argus Cintar in 1940

- Lens aperture scale changed from 3.5, 4.5, 6.3, 11, 18 to 3.5, 4.5, 6.3, 9, 12.7, 18 in 1940

- Addition of Weston film reminder dial on the back in 1940

- Ten shutter speeds reduced to seven in 1941

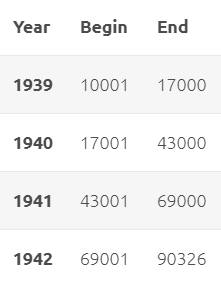

You can tell which year your C2 was made by looking at the serial number in the film compartment which will either be stamped in paint behind the take up spool, or pressed into the Bakelite beneath the film gate. For the cameras with the number stamped into the Bakelite, there is a prefix of ’02’ that can be ignored. According to

You can tell which year your C2 was made by looking at the serial number in the film compartment which will either be stamped in paint behind the take up spool, or pressed into the Bakelite beneath the film gate. For the cameras with the number stamped into the Bakelite, there is a prefix of ’02’ that can be ignored. According to

Fun Fact: Around 1939 or perhaps 1940, a small number of Argus C2 and C3 cameras were exported for sale in Great Britain under the name “Minca Speed Camera”. Not only were the cameras packaged under the Minca name, but the 50mm lens is identified as a Minca Cintar.

The image to the right shows a Minca C2’s original packaging.

C3 Prewar (1939 – 1942)

With the release of the C2, Argus wasn’t done improving upon the original model as in early 1939, they released a third model called the C3 which added flash synchronization to the coupled rangefinder of the C2. In addition to internal changes to the shutter, the camera would receive two holes on the camera’s right side that allowed a proprietary Argus flash gun to be connected.

The new C3 carried a $5 premium over the C2 and originally sold for $30 in 1939 but had risen to $45.05 by February 1942 due to rapid inflation as a result of the ongoing war in Europe. Each of these prices compare to $550 and $700 respectively, today.

When Gustave Fassin designed the Argus C, he likely had no idea how successful it would be or that it would be produced for another 28 years. He also likely did not intend for it to be a war time camera, but it’s rugged and reliable design proved to be a popular choice for soldiers wanting to photograph the war.

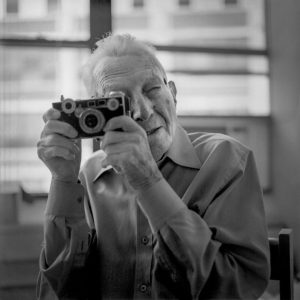

Perhaps the most well known use of someone using an Argus during war time, was Pfc. Tony Vaccaro who in 1941 purchased an Argus C3 for the price of $47 and upon being drafted into the US Army in 1943, took it with him to fight in the war. Vaccaro was a private in the 83rd Infantry Division of the U.S. Army and fought in Normandy, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. Often used as a scout, this gave Vaccaro many opportunities to get out and take photos. He was not an official Army photographer however, so he was responsible for acquiring, carrying, and developing his own film.

He would borrow helmets from other soldiers to use as tanks developing his film and would hang the negatives from tree branches to dry. After developing, he would carry his negatives with him until he could get them somewhere safe. It is estimated that Vaccaro shot over 8000 images on his Argus C3, many of which have become iconic war time photos. If you’ve ever seen a battlefield image from World War II, there is a good chance it was shot on a Prewar Argus C3 either by Vaccaro or someone else.

In 2016, HBO Documentary Films created “Underfire: The Untold Story of Pfc. Tony Vacarro” in which he talks about his time shooting his C3 during the war. Last August, EMULSIVE interviewed Tony Vaccaro in an article called “I am Tony Vaccaro and This is Why I Shoot Film”, in which Vaccaro talks more about his experiences in the war, and why he continues to shoot film.

In 2016, HBO Documentary Films created “Underfire: The Untold Story of Pfc. Tony Vacarro” in which he talks about his time shooting his C3 during the war. Last August, EMULSIVE interviewed Tony Vaccaro in an article called “I am Tony Vaccaro and This is Why I Shoot Film”, in which Vaccaro talks more about his experiences in the war, and why he continues to shoot film.

The C2 and C3 were produced concurrently and saw many of the same cosmetic variations such as the switch from ten to seven shutter speeds and the addition of a Weston film reminder dial. Other than serial number, the most obvious way to tell the difference between the two is the presence of the two flash sync ports on the camera’s side.

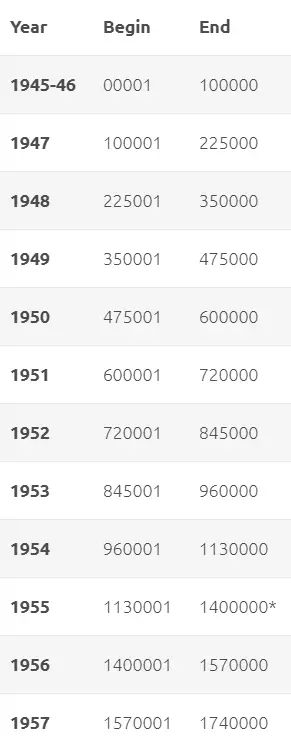

Like the C2, the exact year of manufacture can be determined by the serial number which can be found either behind the take up spool, or stamped into the Bakelite beneath the film gate in the film compartment. Serial numbers behind the take up spool have a prefix of ‘C3′ and serial numbers in the Bakelite have a prefix of ’03’ that can be ignored.

C3 Postwar (1945 – 1953)

During the United States’s involvement in World War II, Argus stopped producing cameras and concentrated on manufacturing goods for the American war effort such as radios, power supplies, and other optical products. When production resumed in late 1945, the Argus C3 returned mostly unchanged.

The first cameras produced until mid 1946 had the same uncoated Argus Cintar lenses, non standard aperture scale, chrome cocking lever, and blue tinted rangefinder as the prewar cameras did. I have no evidence of this, but it’s plausible that these cameras were built from left over parts from the earlier cameras. Whatever the case, by July 1946, C3s with coated lenses, a standard f/stop scale, black painted cocking lever, and yellow tinted rangefinder began to appear.

The years following World War II were some of the most successful for the Argus C3 as people remembered it’s popular reputation from before the war, but with a shortage of cameras from Germany, that left American companies like Argus as the sole providers of new cameras for returning soldiers.

Inflation caused the price of the postwar cameras to rise by 1949 to $78.08 including a case and flash, which when adjusted for inflation is comparable to $850 today which seems high, but if you consider in 1949, a Leica IIIC with f/3.5 Elmar sold new for $280, it was still quite the bargain.

The price of the C3 continued to fluctuate in the early 1950s, dropping to $59.99 in early 1950, and then back up to $66.50 in 1951, and finally $69.50 in 1953. Despite the varying prices, when adjusted for inflation, all three of these prices are comparable to around $650 today.

The C3 remained largely unchanged over the next several years with only a couple minor variances:

- The Weston film reminder dial on the back of the camera was replaced with one with ASA speeds in 1948

- A rectangular “Argus” badge appeared in the bottom left front corner of the camera in 1950

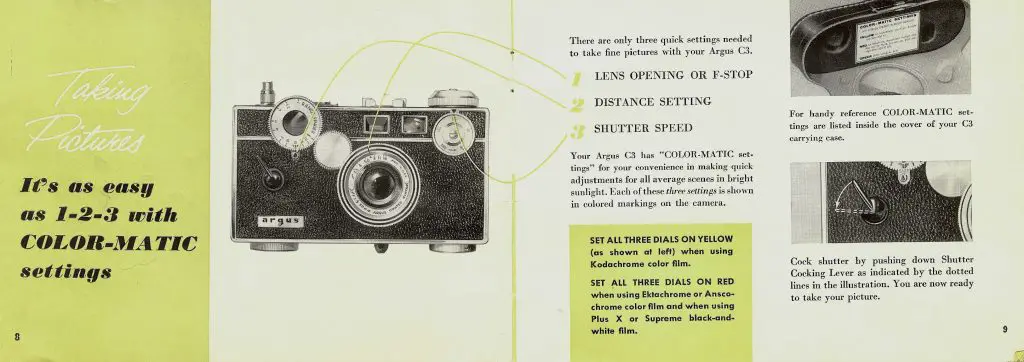

In 1954, a slightly revised C3 made it’s debut unofficially referred to as the C3 Colormatic. The use of the word “Colormatic” was used in Argus literature to refer to color coded numbers on the shutter speed dial, lens, and focusing scale that was there to help novice photographers get accurate snapshots in average lighting. The red markings were designed for Kodak Ektachrome or Anscochrome color film, or Plus X or Supreme black and white film. The yellow markings were for Kodachrome film. The shutter speed for 1/25 was also coded in green which was to be used with flashbulbs, indicating the correct flash sync speed.

An often overlooked feature of the C3 Colormatic was that for the first time, the camera supported electronic flash synchronization at all speeds when using an electronic flash. You still had to use an Argus flashgun, but you could get X-sync at speeds as fast as 1/300, which the earlier cameras could not do.

The C3 Colormatic also removed the circular ASA film reminder dial on the back door of the camera, instead having three separate strips of body covering separated by chrome trim. In 1957 only, the chrome trim was removed and the back door of the camera had a large single piece of body covering.

Although the C3 was nearly 20 years old, it was still a popular camera and between the years of 1954 and 1957 an average of about 150,000 were sold making these very common on the used market today.

Both the Postwar and Colormatic cameras can easily be dated using the serial number stamped into the Bakelite on the inside of the film compartment. Unlike the Prewar cameras, there is no prefix to the serial numbers. The chart to the right shows a wide range of serial numbers including both the original Postwar and Colormatic C3s.

Standard C3 and Match-Matic C3 (1958 – 1966)

The 1950s saw a great number of changes in the camera industry. The rise of quality Japanese cameras, a preference for SLR cameras over rangefinders, and the introduction of “electric eye” auto exposure cameras, so as the decade was coming to a close for there to still be a pre-war camera available for purchase must have seemed a bit odd to many potential customers.

Throughout the 1950s, Argus released several other models, many of which were much more advanced than the C3 and improved on most of it’s features, but the extreme reliability and performance of the C3 kept it a popular choice. While there were a great many minor changes to the camera, not much had changed since it’s introduction in 1938, and as a result, in 1958 Argus gave the camera it’s first real refresh.

Argus had already used the name C4 for a completely different camera, so for these new models, they were called the Standard C3 and Match-Matic C3. Upon it’s release in 1958, the Match-Matic had a list price of $74.95 whcih when adjusted for inflation, compares to $650 today which is consistent with inflation adjusted prices from the early 1950s. I was unable to find any pricing or advertising materials for the Standard C3, but I have to imagine it was the same.

Both the Standard and Match-Matic gained a new flat top shutter release button, an accessory shoe, and an accessory selenium cell exposure meter that was sold with every camera. The meter was mostly the same between the Standard and Match-Matic with the only difference between the LS-3 meter included with the Standard uses aperture f/stops and the LC-3 meter used the Match-Matic’s numbering system.

The accessory shoe also allowed for standard auxiliary viewfinders to be used for the wide angle and telephoto Argus lenses that were available. Prior to these models, the only auxiliary viewfinders were clip on types made specifically for the C3 that attached to the front and rear viewfinder windows.

The standard Cintar 50mm lens got a redesign too with a brushed aluminum exterior ring and a built in Series V retaining ring to allow for drop-in filters and other lens accessories.

Perhaps the biggest change for the Match-Matic was a new simplified exposure system that completely did away with standard shutter speeds and aperture f/stops.

Instead, the shutter speed selector and lens had a numbering scale that when added together was supposed to match up with a corresponding numbering scale on the attached meter. This was thought to be easier for novice photographers as they didn’t need to know anything about shutter speeds or f/stops. If the exposure meter was pointing to the number 12 on the meter, any combination of shutter speeds or lens apertures that added up to 12 would give proper exposure. The idea of a Match-Matic type system was not unique to Argus as other companies such as Minolta had them on their Autocords and other cameras.

The Standard C3 also came with the redesigned lens with Series V filter capability, an accessory shoe, and an included light meter, but continued to use normal f/stops and shutter speeds.

One final change for the Match-Matic was a very distinct two tone beige/tan and black body covering on the camera. The Standard C3 retained the original’s all black design. This, combined with the retro 1930s brick like shape makes the Match-Matic C3 one of the most distinct looking cameras of all time.

With the Standard and Match-Matic cameras, came a new serial numbering system. Instead of being stamped inside of the film compartment, serial numbers were now on the bottom of the camera and were eight digits long, with the fourth digit being a date code indicating which year the camera was made.

With the Standard and Match-Matic cameras, came a new serial numbering system. Instead of being stamped inside of the film compartment, serial numbers were now on the bottom of the camera and were eight digits long, with the fourth digit being a date code indicating which year the camera was made.

There are inconsistencies with cameras made in 1958 that did not follow the usual pattern, which Phillip Sterritt covers in his Argus Dating Guide but otherwise every other year follows the pattern shown in the chart to the left.

Golden Shield by Argus (1960 – 1961)

In 1959, Argus Inc. was acquired by Sylvania Electric Products Inc., who themselves had merged with General Telephone to form General Telephone and Electronics (GTE) and one of the other companies owned by Sylvania was the Golden Shield Corporation of Great Neck, New York.

The “Golden Shield” brand was exclusively sold through jewelry stores across the country in an effort to get more household products into the hands of buyers by “blinging” them up with gold trim and a fancy name plate. The price of the camera was sometimes listed as $64.95, but was more commonly offered as part of an installment plan with monthly payments.

Golden Shield was not limited to just cameras, as there existed a huge range of products like radios, typewriters, blenders, and vacuum cleaners. The ad to the right comes from the December 10, 1961 issue of the Decatur Herald and shows an ad for Carson Jewelers and their whole line up of Golden Shield products.

The image to the left is of a “Golden Shield by Smith-Corona” typewriter. Radio collector Joe Haupt, has a Flickr album of various Golden Shield radios in his collection if you’d like to see more.

The Golden Shield by Argus camera is identical in function to the regular Match-Matic, even using the same Match-Matic exposure numbering system and light meter. Golden Shield serial numbers even fall within the range of Match-Matic cameras suggesting these started off as normal Match-Matics and reskinned at a later time. The only difference was a textured metal foil body covering and a rectangular black, red, and gold name plate on the front of the camera where the normal Argus logo would appear.

I found several references to Golden Shield cameras and other products in newspapers all over the United States in the early 1960s, suggesting this was a nationwide roll out. One site even suggests that there was a Golden Shield catalog for the 1960 and 1961 Christmas seasons, but I was unable to find an example of one.

Argus never maintained official production numbers for it’s cameras, but it is estimated that about 2000 of them were ever made, making them one of the rarest of the entire Argus C-series.

Since the Golden Shield is not any different than a regular Match-Matic, there’s not much else to say about them, so here is a gallery of some more pictures I took of mine.

Lenses

The original Argus C was designed to be an interchangeable lens camera and that feature was retained throughout the entire series until the last Match-Matic cameras were produced in 1966.

The Argus’s mount is a simple screw mount with a diameter of about 33mm, but with the coupled rangefinder gear present on the Argus C2 and all later models, swapping lenses is a little tricky. I’ll get to changing lenses later, but for now I’d like to cover the various lenses available for the C3. Most people are aware of the German made Enna Sandmar 35mm f/4.5 and 100mm f/4.5 lenses as they were heavily promoted by Argus, but there were quite a few other ones available as well.

Starting with the standard Argus Cintar lens included on every C-series camera, this was the only lens produced by Argus directly. It is a Cooke Triplet with three lens elements in three groups. Many sites refer to the Cintar as a Leitz Elmar copy, but it is not as the Elmar is a four element in three groups design. They may have both derived from an earlier Cooke design, but the Cintar is not a copy of the Elmar.

Like the Elmar though, the Cintar’s simplicity works in it’s favor as it’s a surprisingly capable lens that delivers sharp and contrasty images with very little undesirable qualities like aberrations, coma, or vignetting which is characteristic of lesser lenses.

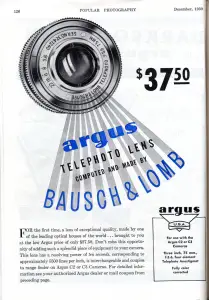

Ads as early as 1938 refer to the Argus C as having an Interchangeable Lens mount, but additional lenses did not become available until at least 1939 when the first mention of a 5-element 75mm f/5.6 telephoto lens made by Bausch & Lomb was available. The ad on the right from the Abe Cohen Exchange’s 1940 catalog shows the lens for an additional $37.50, which is more than the total cost of the camera. Phillip Skerritt’s Argus Rarities page has a picture of an Argus Camera box with a sticker indicating that it has the Bausch & Lomb lens included which suggested they were sold as a kit.

For reasons I was unable to discover, the relationship between Argus and Bausch & Lomb did not continue. There were a couple other companies who made accessory lenses for the C-series, such as Angenieux, Fujita and Soligor, but the most common was Enna-Werk Munchen who produced a 35mm wide angle and 100mm telephoto using the brand name, Sandmar. The two Sandmar lenses were heavily promoted by Argus and at some point were referred to as “Argus-Sandmar” lenses.

Here is a complete list of all known lenses developed for the Argus C-series. Some of these were produced in very limited numbers, which could suggest they were prototypes or special order lenses.

- 35mm f/4.5 Enna-Work Sandmar (in black and chrome)

- 35mm f/3.5 Fujitar Wide

- 35mm f/3.5 Soligor

- 35mm f/4.2 Zeika Wide (rare, ~10 known to exist)

- 35mm Angenieux (extremely rare, ~5 sets made, came with 100mm lens)

- 35mm f/3.5 Robin

The 53mm f/2.0 Enna Werk Lithagon was the fastest lens ever created for use with the Argus, and is extremely rare. Image used with permission, Phillip Sterritt. - 50mm f/3.5 Argus Cintar (Cintar name first used in 1940, early and later versions)

- 53mm f/2.0 Enna-Werk Lithagon (rare, 3-4 made)

- 75mm f/5.6 Bausch & Lomb (uncommon, ~1000 made)

- 100mm f/4.5 Enna-Werk Tele-Sandmar (in black and chrome)

- 100mm Angenieux (rare, ~5 sets made, came with 35mm lens)

- 135mm f/4.5 Fujitar

- 135mm f/4.5 Robin

- 135mm f/4.5 Soligor (in black and chrome, also Elitar-Soligor variant exists)

I did not have access to any of the rarer lenses in the list above, but I do have examples of the 35mm and 100mm Sandmars and the 135mm Soligor, so I thought it would be interesting to compare the three to get an idea of the range of focal lengths available to the camera.

The gallery below was shot on Kodak Vision3 50D film using the C3 Standard, and shows the same scene using the three accessory lenses, plus the 50mm “Standard” Cintar.

As you can see from the four images above, the focal length of the scene above changes from the widest at 35mm to the longest at 135mm, but what’s even more interesting is how each lens renders things a bit differently.

The 35mm Sandmar and 50mm Cintar both render sharp images with little vignetting. The sky takes on a cooler color with the 50mm lens than the wide angle. With the 100mm Sandmar, the sky retains a cool hue, but vignetting is clearly evident in the whole image. Center sharpness is still pretty good. The last image from the Soligor 135mm suffers from camera movement, which is my fault, but the colors seem washed out and there is heavy vignetting near the corners, almost like the lens has gone beyond it’s circle of coverage. I’ll have to experiment more with this lens in the future to see if I can improve things at all.

Using the Argus C3

If you’ve made it this far, it’s probably no surprise that for me to have put this much time and effort into this article, I must be a pretty big fan of the camera, and you’d be right.

I absolutely adore the Argus C3 and it’s entire family. Part of my fondness is due to the C3 being one of the first vintage cameras I ever handled, and the very first I ever reviewed on the site, but I also have a general appreciation for American made cameras in general. While Germany and Japan clearly were far more adept at making cameras, and had much longer histories doing so than the Americans, I like that pretty much every American camera was it’s own design. There were very few American cameras that look like anything made by the competition. Both the Soviet and Japanese camera industries got their starts copying German designs, and even within Germany, many companies were competing with each other, whereas the Argus released this solid brick of a thing to the masses, and it ends up staying in production for 28 years. What a story!

Not every collector has my level of appreciation for these cameras, and I completely understand why. The ergonomics aren’t very good, they’re crude, each time you fire the shutter, it sounds like someone is snapping a metal fork in half, and they’re not exactly pretty (at least that’s what other people say, I like their look.)

But if you’re looking to get started with film photography and want something different than another German rangefinder or Japanese SLR, the Argus is a fine choice. It has a lot of history, once you learn how to use it, it’s not that hard to use, and the lenses are capable of some really nice shots.

Note: For the remainder of this section, I will be using a prewar Argus C3 as it’s control layout is similar to most Argus C-series cameras you’ll find out there. There are a few minor differences with the later Standard, Match-Matic, and Golden Shield variants, which I’ll cover when necessary, but otherwise, everything you see here applies to all cameras.

Starting with the front of the camera, we see the shutter speed dial in the upper right corner. The number of speeds changed quite a number of times throughout the whole series starting as high as 10 speeds, down to 5 by the end. This wheel is designed to be rotated counter clockwise from the fastest speeds to the slowest. You can turn the dial clockwise, but you will feel a stop around 300. Do not try to force this wheel past 300 when turning clockwise (you can do it counterclockwise) or else you may break something.

Regardless if you have a 10, 7, or 5 speed model, the Argus’s slow speed escapement is infinitely variable, which means that in between speeds are possible. The numbers printed on the dial only seem to be approximations of what will fire at that point, but if you want something in between 100 and 300, you can do that. From everything I’ve seen online and while disassembling these cameras, the design of the shutter and slow speed governor never seemed to change, which suggests that the same numbers of speeds are attainable regardless of which variant you have. If anyone reading this has any information counter to my theory, please let me know in the comments section below.

On the left side of the camera is the rangefinder wheel, which is coupled to the lens on all versions of the camera except the original Argus C. The rangefinder has a base that’s approximately 44mm wide, which is just slightly longer than a Leica II/III for improved accuracy and has a range of 3 feet to infinity.

Fun Fact: Although all production Arguses had a focus scale in feet, a very small number made in the late 1930s had a metric scale. It is thought that these were made for special medical or scientific applications.

Below the rangefinder is the cocking lever. This lever must be pressed before each exposure, otherwise the shutter will not fire. The Argus C-series does not have double image prevention so you are free to make as many intentional exposures as you like on the same frame.

Pro Tip: One of the ergonomic failures of the entire C-series is that the cocking lever is in a position that is easily bumped by your hand while shooting the camera. Upon firing the shutter, the cocking lever needs to move freely back to it’s original position and any interference by your hand will delay the closing of the shutter, throwing off your exposure.

A really great tip is to rotate the lever 180 degrees so that it points toward the lens mount when cocked. To do this, you simply back off the cocking lever by rotating it clockwise (the threads are reversed, so it’s ‘righty loosey’ and ‘lefty tighty’ and then loosening the hex nut behind it just a little bit so that you can tighten the cocking lever and leave it pointing in a different direction than normal.

This might take some trial and error to get it rotated correctly, but when you’re done, it should look like the one in the image to the right. You still need to be careful when holding the camera, but at least this way, the long part of this lever will be facing away from your hand.

Perhaps one of the more notorious features of the Argus C2 and C3 is it’s interchangeable lens mount. Many people who are not fans of these cameras identify the lens changing procedure to be one of the camera’s worst features. My thoughts on this is that yes, the process for changing lenses isn’t ideal, but I also think it’s not nearly as difficult as some people suggest it is.

There is a ton of information online, including reading the original owners manual for the camera, that show how to change lenses, but I thought that making a video and showing it done with three different lenses would be helpful, so that’s what I did.

Although not shown in the video, when using any lens besides the 50mm Cintar, you must use an auxiliary wide angle or telephoto viewfinder such as the one in the image to the right. If you’re using a later C3 Standard, Match-Matic, or Golden Shield with an accessory shoe, you may use any viewfinder made for any camera, not just Argus. For the earlier models like this one here, there are Argus specific ones that clip onto the top of the camera over the front and rear viewfinder windows.

As mentioned in the video, if after mounting an accessory lens, the focus scale is not pointing up, you may adjust it by loosening small grub screws in the lens threads. Phil Sterritt has some instructions on how this is done.

The backs changed over the years, some having three sections of leather, some with one, some have a film reminder dial with Weston speeds, some with ASA speeds. Regardless of which one you have, the back of the camera has two round eyepieces for the main viewfinder on the left and the rangefinder on the right.

The back of the camera is secured with a chrome latch on the camera’s left side. This latch has a small hook on it that must be pressed inward to overcome. While putting inward pressure onto the latch, pull back on the rear door and it will open.

The right hinged door reveals a film compartment in which film travels right to left. This is contrary to how many 35mm cameras work from later in the 20th century, but in 1938 when this camera was first designed, it was pretty normal for film to travel this way.

When loading a new cassette, you must first pull out the rewind knob on the bottom right of the camera. Extend the leader across the film gate and onto the fixed take up spool which has a single large slit going through the middle. The Argus C-series is designed in a way where there is no need for light seals, so typically light leaks shouldn’t be an issue with these cameras.

The bottom of the camera has the rewind knob and a matching foot with an integrated 1/4″ tripod socket, and mini kickstand protrusion for keeping the camera level while sitting on a flat surface.

On top from left to right is the large film advance knob. It’s size makes getting a grip on it easy for advancing film.

If this were a C3 Standard, Match-Matic or Golden Shield, there would be a standard accessory shoe to the immediate right of the advance knob, but that doesn’t exist on the earlier models.

The large chrome circle with the two divots in it is a port for accessing a rangefinder adjustment screw. I explain in the Repairs section earlier in this article how to service the rangefinder either using this port or by removing the rangefinder altogether.

Next is the exposure counter and hexagonal film interlock release switch. The exposure counter is additive and must be manually reset upon loading each new roll of film. Like most 35mm cameras, when advancing film, the film advance will lock when you’ve reached the next exposure. This prevents you from continually advancing the film, wasting unexposed film like you might on an early roll film camera. The interlock release must be pressed prior to advancing the film to each additional exposure. To do this, give a gentle leftward pressure on this switch while turning the film advance knob. Once the interlock has been overridden and the knob starts to turn, you may release pressure on the interlock.

This interlock is also used to rewind film back into the cassette at the end of the roll. By maintaining constant pressure on this switch, you may turn the rewind knob on the bottom of the camera until all of the film is in the camera. While rewinding, the exposure counter will rotate, which is helpful if you want to leave the film leader out of the cassette. Keep rewinding until the exposure counter stops turning, and the leader will be left out of the cassette.

Finally we have the shutter release. The design of the shutter release has changed over the years, from the “mushroom” style of the original models, to the upright threaded one seen here, to the flat design of the later models, but they all support both Instant and Bulb modes.

With the shutter release in Instant mode, the shutter fires at whatever speed the front dial is set to. Rotate it to the B position and the shutter works in Bulb mode, where the shutter will remain open for as long as you provide pressure on the shutter release. This mode also disables flash synchronization on all C3s, disabling the flash. With a locking shutter release cable, you can effectively have a Timed mode in which you could lock the shutter open for very long exposures.

Like pretty much every 35mm rangefinder camera from the 1930s, the viewfinder and rangefinder windows are separate. Although this might seem unusual to someone only familiar with modern cameras, the split window design actually has a benefit in that the main viewfinder window is very bright and easy to compose with. Because the rangefinder window is separate from the main viewfinder, it can be magnified separately, improving your ability to see the split image. The downside of course is speed, because you have to shift your eye between two different windows, but other than that, rangefinders like that of the Argus C-series are usually easier to use than the combined coincident image style that was increasingly popular in the 1950s and 60s which become cloudy and harder to use over time.

Earlier Argus C-series cameras used a blue tinted rangefinder, but this was changed with the postwar models to have a yellow tinted rangefinder, but other than color, the two designs work exactly the same.

My Results

I did not have the time to shoot each and every Argus C-series model in my collection, so for the gallery below, I am including samples shot on three different models. Starting with the oldest to newest, I selected a roll of ORWO NP55 that expired sometime in the 1970s for the prewar Argus C3, whose serial number suggests it was made in 1940. I thought that by choosing a slower black and white film, I might recreate a look that those early uncoated Arguses likely would have delivered when they were new.

For the second roll, I shot fresh Fuji 400 color film in the Postwar Argus C3 with the Sandmar 35mm f/4.5 wide angle lens. I brought this camera with me to a Chicago White Sox game and the lower light was ideal for the faster 400 speed film. Even though the lens has a maximum aperture of f/4.5, I figured using a shutter speed of about 100 would match up well with interior shots of the ballpark.

Finally, I shot some Kodak Gold 200 in the C3 Standard. In both of the two earlier cameras, I took the time to clean the shutter and viewfinders and make sure the rangefinder was adjusted so that the camera would work correctly, but this Standard came in it’s original box and was in such nice shape, I thought I could get away with loading it up with film without doing anything to it. Would that be a mistake?

The prewar Argus C3 most closely matches that of the one Tony Vaccaro used in World War II and I wanted to use an older film that might capture a similar look to what he got, and I think I did. The uncoated Cintar lens loved the ORWO film, producing very natural looking images with good, but not overpowering contrast, good sharpness, and a ton of shadow detail. I have shot color film on uncoated cameras before so I’m used to that pastel/washed out look that you often get, so I was quite happy to see these results.

If I was going for a purely 1940s American shooting experience, I probably should have used something like Kodak Panatomic-X or perhaps even something more modern like Tri-X, but I’m very happy with the ORWO film and the images it made.

The second gallery was my first ever attempt at shooting an Argus with anything but the 50mm Cintar and I was astonished at how easy it was. Using the Argus clip-on viewfinder actually improved the shooting experience as nearly all of the images I shot were at or near infinity, so I never had to touch the rangefinder, so I was free to use the large and bright viewfinder for most of these images. Even when I did change focus, like in the images of the statue, corn, and yellow flowers, moving from the in-body rangefinder for focus, and the clip-on viewfinder for composition was not difficult at all.

The Enna-Werk lens is quite sharp, sharper even than the Cintar, and I loved the look I got from it. On any camera system, I tend to favor slightly more wide angle lenses over 50mm primes as that’s how I tend to see the world. I already had a high level of appreciation for the Argus C3, but with the 35mm Sandmar, my fondness for it grew. I love the 35mm Sandmar so much, it’ll likely take precedence over the 50mm Cintar on future rolls through my C3s.

This third gallery comes from the C3 Standard which I didn’t think I needed to do any kind of restoration as it was in such good shape. These images are my least inspired as they were just random walkabout images of stuff around my house and work, but in a way, these are the kinds of images the Argus was designed to capture. This was a camera originally priced to match the weekly salary of the average American worker and those were the people who usually bought them.

I did miss focus on a few images, especially indoors where I didn’t have the benefit of a wide depth of field, which suggests the rangefinder could benefit from some calibrating, but overall they’re not bad. The 50mm Cintar still delivers great sharpness and bright colors. I think the next time I take out this camera, I’ll check the rangefinder first, and then try a slower color film like Ektar or perhaps even Kodak Pro Image 100 to see how vibrant that later coated lens delivers.

So do I like the Argus C3? I think that after typing over 13,000 words over the course of 5 posts, it should be pretty clear that I am a big fan of these cameras. I love the Argus C-series for it’s looks, it’s history, it’s quirks, and it’s performance.

It does take some extra effort to shoot, but that makes it fun to me. For as great as Barnack Leicas are, so many were created that once you’ve shot one, you’ve shot them all. By the late 1950s and especially early 1960s, most cameras being sold (especially Japanese ones) were sterile and largely worked the same way. Sure, there were still oddities here and there, but nothing truly unique anymore. Shooting the C3 takes you back to those early days when the control layout and ergonomics were not fore gone conclusions.

I like the shape of the camera with hard corners, I like the separate viewfinder and rangefinder windows, I like the lens mount, the right to left film transport, and the film interlock release. I think these all add character to the camera. If I had to pick one thing I wish Argus had done differently, it would be the location of the cocking lever or heck, even a self-cocking shutter. Theodore Brueck’s patent design from 1938 hints at a version of the Argus shutter with this feature, and I wish that it was built this way.

I know that this article won’t change the minds of those who think the Argus C-series isn’t for them, but at the very least, I hope you’ve enjoyed the history and can at least agree that in the right hands, they are capable of nice images. These cameras show up so often and for so little, I see no reason why everyone couldn’t give one a try. Maybe you won’t have the same fondness for them as I do, but maybe you will.

There’s plenty of other people who have shot C3s over the years and you can find many galleries of other people’s works online, but one that I found which I thought was especially interesting was the work of Marco Balma, who has a whole Flickr gallery of images he shot with an Argus C3. Check out his images if you have the time.