This is an Asahiflex IIa, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera, produced by Asahi Optical Company from February 1955 to April 1957. The model IIa was an upgrade to the original Asahiflex from 1952 featuring a front mounted slow speed dial with speeds down to 1/2 second, and an instant return mirror. The Asahiflex was the first Japanese camera and second overall to have this feature, which helped eliminate one of the objections of the SLR over more popular rangefinder cameras. The Asahiflex was a critically important camera for the Japanese camera industry, as it not only established Asahi (later Pentax) as a world class camera maker, but it would set the stage for an onslaught of Japanese SLRs that would appear over the next five years, forever changing the landscape of photography.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

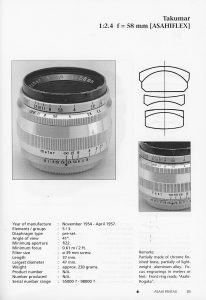

Lens: 58mm f/2.4 Asahi-Kogaku Takumar coated 5-elements

Lens Mount: Asahiflex M37 Screw Mount

Focus: 2 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Waist Level Finder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1/2 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: M and X Flash Sync, no accessory shoe

Weight: 745 grams (w/ lens), 515 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pentax_pdf/pentax_asahiflex_II-single.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Asahiflex IIa is the best featured of the early Asahiflex, featuring an instant return mirror, a fixed waist level finder, and with the 5-element f/2.4 Takumar, a very capable and sharp lens. Like later Pentax cameras, the Asahiflex is beautifully built with almost perfect ergonomics, and when found in working condition is a very capable shooter. These cameras aren’t common today and with a lens, can be quite expensive, but if you have an opportunity to pick one up at anything close to a good price, I highly recommend it! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance and above and beyond quality | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

History

Asahi and Pentax are two names that long have been associated with some of the best optical products Japan has ever made. Originally founded in November 1919, by Kumao Kajiwara in Toshima, Japan, a suburb of Tokyo as Asahi Kōgaku Goshi Kaisha, (Asahi Optical Joint Stock Co.), the company produced a variety of lenses and other optical products for the burgeoning Japanese optical industry. The use of the word “Asahi” in its name was a common theme among Japanese companies as Asahi loosely translates to “morning sunrise” which was a symbol of the Japanese people, and was the inspiration for the red circle on the Japanese flag. There were even other optical companies that used the name “Asahi” such as Asahi Bussan G.K. who distributed a series of unrelated Olympic cameras in the 1930s.

Asahi and Pentax are two names that long have been associated with some of the best optical products Japan has ever made. Originally founded in November 1919, by Kumao Kajiwara in Toshima, Japan, a suburb of Tokyo as Asahi Kōgaku Goshi Kaisha, (Asahi Optical Joint Stock Co.), the company produced a variety of lenses and other optical products for the burgeoning Japanese optical industry. The use of the word “Asahi” in its name was a common theme among Japanese companies as Asahi loosely translates to “morning sunrise” which was a symbol of the Japanese people, and was the inspiration for the red circle on the Japanese flag. There were even other optical companies that used the name “Asahi” such as Asahi Bussan G.K. who distributed a series of unrelated Olympic cameras in the 1930s.

Asahi Kōgaku Goshi Kaisha’s earliest products were lenses for eyeglasses, which gave them quite a lot of experience in the cutting and polishing of optical glass. With this skill, in 1923 they expanded their portfolio to projection lenses, binoculars, and other scopes. Early Asahi products were sold under the brand name “AOCO” which likely was an abbreviation for Asahi Optical COmpany. The AOCO logo would continue to be used on Pentax products throughout a large portion of the 20th century.

Quickly establishing themselves as a skilled maker of lenses, in the 1930s Asahi expanded once again into the market of camera and photographic lenses. Asahi’s photographic lenses were not sold under their own name, but rather under the names Zion and Optor which were produced for other Japanese companies like Konishiroku and Molta, who would both later become Konica and Minolta, respectively.

It is unclear whether Asahi designed the lenses, or just manufactured them to the specifications of their customers, but whatever the case, their previous abilities with eyeglasses and projection lenses gave them ample capacity and speed to make the lenses quickly, allowing both Konica and Minolta to establish themselves in Japan’s early camera industry.

In 1938, company founder Kumao Kajiwara passed away and an Asahi employee named Saburo Matsumoto took over. The company was reorganized by the Japanese government and its name was changed to Asahi Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K. and it produced optical products for the Japanese military up through the end of the war.

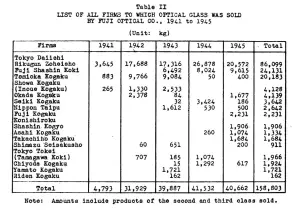

There is little information about Asahi’s exact role during this time. Did they produce lenses used in the assembly of military products by other companies, or did they supply complete optical assemblies such as binoculars or other kinds of scopes? In a study by the US Navy in August 1945 of Japan’s optics industries, it was found that Asahi Kogaku was a purchaser of glass produced by Fuji between 1943 and 1945. The reason for this is that Asahi would not have had the ability to melt down their own optical glass, requiring them to buy it from Fuji, who did.

By the end of the war, nearly all of Asahi’s factories in Japan were destroyed and the company was forced to close, but only for a short time. In 1948 (some sites suggest 1946, but I believe 1948 to be correct), Saburo Matsumoto was able to convince the occupying American forces to help re-establish the company in a new factory, this time as Asahi Optical Company, Ltd.

Like other Japanese optical companies of the late 1940s like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta), Seiki Kogaku (Canon), and several others, Asahi was required to produce optical products exclusively for export. Their first product was a telescope, produced in the spring of 1948 made specifically for viewing a total eclipse of the sun in Japan that year. The telescope was made out of cardboard but used Asahi’s high quality lenses and was quite popular. Later that year, they released a set of Jupiter binoculars which were of much higher quality than previous designs, and helped to establish Asahi as a worthy competitor in the Japanese optical market.

With the company on a roll, Matsumoto wanted to expand into photographic cameras and sensing a crowded market of German rangefinder cameras and other Japanese companies who were copying their designs, in 1949 he decided to pursue a Single Lens Reflex design.

The earliest Asahi SLR designs were not successful, and forced Matsumoto to reach out to his colleague Ryohei Suzuki who he had met while producing lenses for Konishiroku and asked if he would help build an all new 35mm SLR. Intrigued by the idea, but lacking in camera making experience, Suzuki contacted his friend Nobuyuki Yoshida who had the necessary experience working for Konishiroku and also as an independent camera repairman.

With Suzuki and Yoshida on board, Matsumoto had the team he would need to build his new camera. Work began in November 1950 and in a few short months, in May 1951 the first Asahiflex prototype was presented. Such a short turn around time is especially impressive considering the camera was designed entirely from scratch by a team of men who had no experience building a 35mm SLR. It is said that the only reference for what an SLR should be came from an old Kochmann Reflex-Korelle 6×6 SLR that Matsumoto had from before the war. Although 35mm SLRs like the Kine Exakta and Zeiss-Ikon Contax SLR did exist at the time, they were not exported to Japan so were not available for inspiration.

Three working prototypes were finished in October 1951 and presented to both Asahi leadership and the Japanese press. The new camera, now called the Asahiflex got its name by taking the name of the company and adding -flex to the end.

Upon seeing the finished camera and some sample images made from it, Saburo Matsumoto was very excited about his new camera and began to market it immediately. Initial reception was lukewarm however, as the SLR market had not yet grown as rangefinders were still the preferred choice by professional and semi-professional photographers.

Matsumoto was persistent however and eventually gained interest from the optical division of Hattori Tokeiten K.K. (predecessor to Seiko) who agreed to distribute the camera. Production models first went on sale in February 1952 at a rate of about 200 units per month, but quickly expanded to 500 per month, a very good number for a unique camera made by a small Japanese company.

The Asahiflex was an interesting camera as it contained both a non-removable waist level reflex finder along with an eye level Galilean viewfinder on the body of the camera. This second viewfinder was fixed at 50mm and allowed the photographer to quickly frame their image without it being reversed as was the case of all waist level viewfinders.

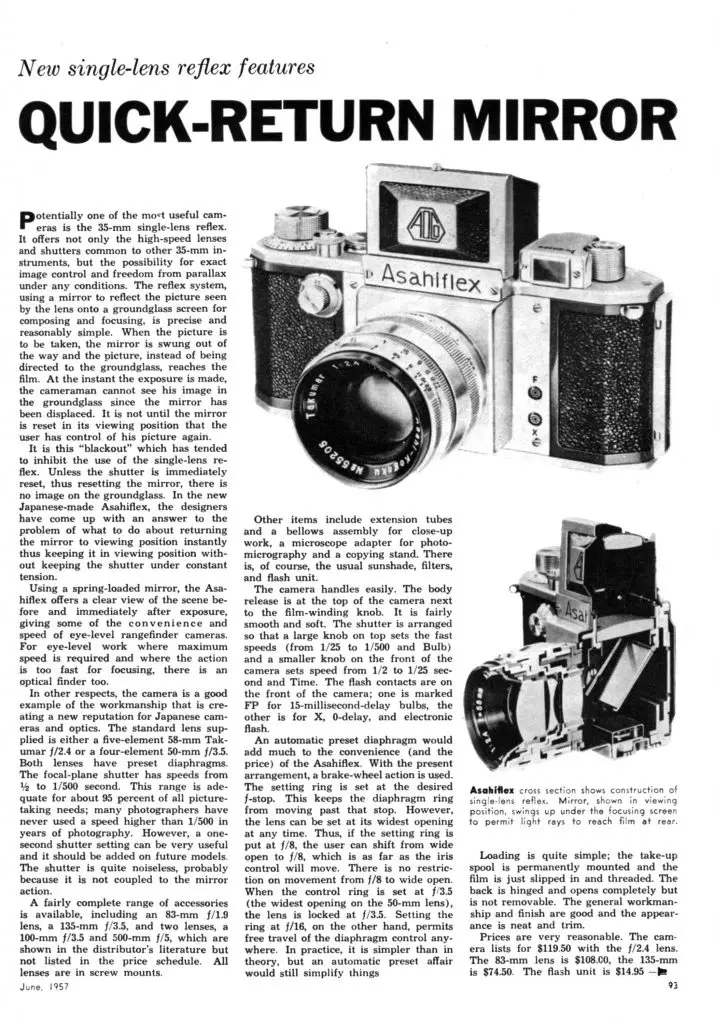

The Asahiflex had a modern (for the time) feature where the reflex mirror was coupled to the shutter release. When the photographer would press the shutter release, the mirror would flip up and remain in the up position for as long as the shutter release was held down. Upon releasing the shutter release, the mirror would return to the down position. This quick, but not instant return mirror was pretty significant for the time as most SLRs of the era had a mirror that would only return to its position when the shutter was cocked.

There were two versions of the original Asahiflex camera, the earliest version which has a single flash sync port for flashbulbs, and an unusual arrangement of shutter speeds. The second version, released in 1953 was called the Asahiflex Ia and added a second X-sync port and had a redesigned shutter that was simpler, more reliable, and changed the shutter speeds to a more standard arithmetic order.

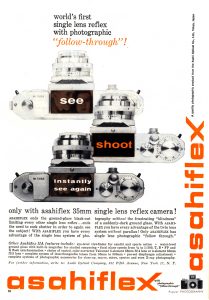

In February 1955 the Asahiflex IIa was released, which had a true instant-return mirror where the mirror would return to the down position immediately after the shutter closed, regardless if the photographer was still holding down the shutter release. This was a necessary upgrade as the IIa also had slow speeds, and using the old method, had the photographer chosen one of the slower speeds and released his or her finger while the shutter was still open would have caused the mirror to drop back down, interfering with the exposure.

At the same time as the Asahiflex IIa’s introduction, an updated model IIb (first released in November 1954) was also released that was identical except lacking in slow speeds. The IIb is easily differentiated from the IIa in that it has a round “dummy plate” in the location of the IIa’s slow speed dial, whereas the earlier cameras just don’t have anything there. This was done so that Asahi only had to build one body style for all their cameras.

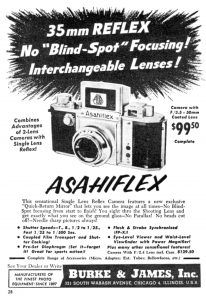

Initially the Asahiflex was exclusively marketed in Japan, but by 1957, Asahiflex branded models were sold in the United States by some distributors like Burke & James of Chicago. The ad to the right shows the Asahiflex IIa with a retail price of $99.50.

Perhaps the biggest source of Asahi cameras in the US was the Sears Roebuck Co who sold them under the names Tower Model 22, 23, and 24. Each of these three cameras were identical in features to the Asahiflex IIa, Ia and IIb respectively. Both the Tower 23 and 24 sold in 1957 for $79.50 with the Takumar f/3.5 lens and $99.50 with the Takumar f/2.4 lens, respectively. These prices compare to $730 and $915 today.

When it was released, the Asahiflex had two things working against it, a relatively unknown name to photographers in the west, and an SLR design that hadn’t yet swayed professional photographers away from rangefinders.

A combination of excellent build quality, excellent lenses, and the successful implementation of an auto return mirror allowed the Asahiflex to win over photographers, proving that not only could the Japanese build quality lenses and cameras, but they could be innovative too. The short review below, from the June 1957 issue of Popular Photography offers quite a bit of praise to the Asahiflex (the IIa model is clearly referenced). Compliments were given to the workmanship and clean design, usefulness of the instant return mirror, the quality lenses, and that the camera is quite affordable. This no doubt helped set the stage for continued success with Asahi’s later line up of Pentax SLRs.

By the mid 1950s, more and more German SLRs featured a pentaprism viewfinder which did not invert the image like on a waist level viewfinder. The first German SLR with this feature was the Contax S released by Zeiss-Ikon in 1949, but prototypes existed from before the war. The need for such a feature was not lost on Saburo Matsumoto, so in 1954 he demanded that a pentaprism version of the Asahiflex be created.

The first pentaprism prototypes look to simply be a regular Asahiflex with a pentaprism grafted onto the top. The camera lost the optical sports finder, but retained the knob wind, slow speed dial on the front, and the M37 screw mount.

As the camera evolved into what would become the first Pentax, the prism became more cleanly designed into the top plate, the camera gained a film advance lever, and the lens mount was changed to the M42 “universal” mount which at the time was exclusively used by German cameras like the Contax/Pentacon SLR, KW Praktica, and Wirgin Edixa Reflex.

The Pentax, along with Asahi’s line of Takumar lenses would go onto become one of the most successful 35mm systems of the 20th century. Their experience at making Single Lens Reflex cameras gave them a huge lead over other Japanese companies like Nikon, Canon, Yashica, and Konica who wouldn’t release their first SLRs until 1959 or 1960.

Pentax SLRs would retain their popularity as the lineup evolved, first with the new bayonet K-mount in 1974, and then with later auto focus and digital designs. The name Pentax still exists today, producing DSLRs manufactured by its parent company, Ricoh Imaging Company Ltd.

Today, nearly every generation of Asahi or Pentax cameras are collectible due to their excellent ergonomics, reputation for reliability, and superb optics. In his Top 20 Cameras of All-Time list published in Shutterbug magazine in May 2008, esteemed camera collector Jason Schneider ranks the Asahiflex IIb as number 15, ahead of other excellent cameras like the Zeiss Contax II, the Rolleiflex Automat, and the Hansa Canon.

Asahiflex cameras often have a special place on collector’s shelves because of their good looks and historical significance. Although the M37 lenses made for the Asahiflex are not as easily adaptable to modern digital cameras as later M42 lenses were, for the people who do manage to do it, they report that the optical quality on modern, high resolution digital sensors is very good. Whether you want to admire them on a shelf or shoot them, this is a camera you’ll definitely want to consider.

My Thoughts

I was so enamored with the Pentax AP and Pentax K after my double review of each camera in September 2019, I became curious about the earlier Asahiflex cameras. The build quality of those early Pentax cameras was on a different level of later cameras and I really wanted to see how good the company was with their first model.

As I began my search for an example I could review, I remembered that my friend Barry from Gary Camera in Merrillville, Indiana had one sitting in a display case in his shop. I visit Barry from time to time asking to scrounge around his “junk bin” of cameras that customers have brought to him, in various stages of disrepair and sometimes Barry lets me buy them off him for bargain basement prices.

The Asahiflex was one I knew he wouldn’t sell me, but after asking very nicely he agreed to loan the camera to me. He said he didn’t think the shutter worked, and upon a quick look at it in the store, I saw that it was hanging. Figuring I could at least do a camera of the dead review for it, I still took it.

As I had commented in the Pentax AP and K reviews, these early Asahi cameras are wonderfully built. While most people immediately think of Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Canon, and Tokyo Kogaku (Topcon) as the premiere Japanese camera makers of the 1950s, I absolutely believe that Asahi cameras were every bit as good in terms of design and quality control.

The top plate has a very “Leica-esque” layout to the controls, with the rewind knob next to a raised platform for the optical viewfinder that vaguely resembles that side of those rangefinders. The fixed waist level finder has an attractive lid with Asahi’s AOCO logo on top. To the right is a single speed shutter speed dial for speeds 25 through 500, plus Bulb.

Like most single speed dials of the era, the shutter speed dial rotates as the shutter fires, so you want to make sure you don’t touch it while firing the shutter as any amount of drag on the dial will throw off the shutter speeds. Changing shutter speeds should only be done after winding the camera on, as the indicated speeds will not line up with the mark when it is uncocked. Slow speeds from 1/2 to 1/10 plus T are selected with the dial on the front of the camera and with the fast dial set at the 25-2 position.

The shutter release has a smooth top to it and is externally threaded for a Leica style shutter release cable. Finally, the film advance knob also doubles as the exposure counter. The counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made, and must be reset manually.

The bottom of the camera has a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket and an A/R switch for advancing and rewinding film.

When looking at a side profile of the camera, the lack of a pentaprism throws off the proportions, making it look extremely long and front heavy. Notice I had to balance the camera with a small pebble beneath the lens. In reality, sitting the Asahiflex next to a Pentax Spotmatic, the camera is no longer front to back.

This side of the camera is where you’ll see the door release latch for the film compartment.

The Asahiflex’s film compartment is surprisingly modern with left to right film transport onto a fixed and multi-slotted take up spool. The pressure plate is spring loaded and has divots on it to decrease resistance as film travels across it.

Off the top of my head, I believe this is the first 35mm SLR feature a film compartment like this with a right hinged film door. Thinking about earlier SLRs, they all had either removable backs like the KW Praktina, had a right to left film transport like the Exakta, or had a left hinged door like the Zeiss-Ikon Contax SLR.

Up front, the camera has what at first glance appears to be a normal screw lens mount. Without a sense of scale, the Asahiflex’s mount doesn’t look any different from later Pentax cameras, but upon closer look, the mount here is much smaller at only 37mm, even smaller than that used by the Leica Thread Mount. Why Asahi chose such a small mount for their first SLR is anyone’s guess, especially considering the M42 mount already existed when this camera was being designed.

In the image to the left, you can see four common screw mounts starting in the upper left corner and going clockwise, the M37 Asahi Takumar, M39 (LTM) Nikkor, M42 Zeiss Tessar, and M40 Praktiflex Zeiss Tessar. Each of these four lens mounts were available for a variety of cameras in the 1950s and at a glance, look similar.

The Asahiflex’s viewfinder is a fixed waist level design, which means you cannot remove it. It wouldn’t have made sense for Asahi to create an interchangeable mount as at the time the camera was designed, no Japanese company had made a pentaprism viewfinder yet.

The viewing screen a solid piece of frosted ground glass that is bright and easy to use outdoors in good lighting, but darkens quickly indoors or when the available light is decreased. There is a hinged magnifying glass on the back flap of the hood that can be used for precision focus, but one feature that is missing is a sports finder in the hood. The most logical explanation for this is the inclusion of the optical straight through finder on the camera’s top plate which accomplishes the same task. Comparing the Asahiflex to the similar KW Praktiflex however, I found the flip down sports finder through the viewfinder hood to be faster and easier to use on the KW than the optical finder on the Asahiflex.

The 58mm f/2.4 Takumar is a preset lens, which means that it does not have an automatic diaphragm. You must manually open the lens to maximize viewfinder brightness when composing your image, and then stop it down again before pressing the shutter release to get the exposure correct.

For someone who has never used a preset lens, it is not as complicated as it seems. Looking at the lens, you’ll see that there are two rings with f/stops on them. The one nearest the lens mount actually controls the opening and closing of the iris. The other one is the preset ring, which acts as a “stop” prohibiting the first ring from going past whatever you set it to. This is useful because whatever the preset ring is set to, you can twist the main aperture ring back and forth between wide open and stopped down, but it won’t go any farther than what the preset ring is set to.

So for example, if you wanted to expose an image at f/8, you would set the preset ring to f/8 before peering through the viewfinder. Then while composing your image, you would grip the aperture ring and turn it all the way to f/2.4 which opens the iris to maximize viewfinder brightness. Then, when you’re ready to press the shutter release, you can turn the aperture ring all the way until you feel it stop without having to check it. This is faster than having to compose your image, and then take the camera away from your eye, to look at the aperture ring while turning it to f/8.

Handling the Asahiflex is incredibly easy. The control layout should be very familiar to anyone whose used any classic film SLR or rangefinder. Build quality is excellent, easily on par with the best German cameras of the day. With a weight of 745 with the Takumar lens, the camera is very dense, but not heavy. Without a lens, the body is 70 grams, or about 12% lighter than the Pentax K, likely due to the lack of a pentaprism.

After that Pentax AP and K review, I had wondered if Asahi’s excellence extended into their earlier cameras, and I am happy to say that it very much does, but what about its images? Does the 5-element f/2.4 Takumar hold a candle to Asahi’s later lenses?

My Results

After handling the Asahiflex for a while and seeing that the shutter wouldn’t consistently fire, I started to realize that I may never get a chance to shoot this camera. About 2 months since I first borrowed the camera from Barry, I picked it up once again and started going through the speeds. I opened the back of the camera and watched the shutter open and close at all the speeds, and I noticed that 1/50 was the only one that fired pretty consistently. The frequency of when it fired correctly would increase the more I used it.

Realizing that my one and only shot at ever shooting this camera would require leaving the shutter speed at 1/50, so I looked through my collection of slower speed film and settled on a motion picture film called Kodak Vision3 50D. Kodak’s Vision3 film is designed for ECN-2 development because it has something called a Remjet coating that protects the film as it moves quickly through a motion picture camera. Although compatible with C41 chemicals, Remjet must be removed separately from normal development. Alternatively, you could just buy the proper ECN-2 development chemicals, which is what I decided to do.

Luckily, my friend Adam Paul turned me onto an Etsy seller named consofcart who sells home made ECN2 kits, so I picked one up and tried my hand at this new color film process.

Before I shoot any camera for the first time, somewhere in my mind there’s a “confidence level” for that particular camera. If it is a modern electronic camera that appears to be in good working condition, my confidence is very high. If it is an old folding camera with iffy bellows, a sluggish shutter, and a hazy lens, my confidence is low.

Considering the condition of the shutter on the Asahiflex and the fact that I made no attempt to mess with light seals (since it is not my camera), I really didn’t expect much from it. Sure, I knew the 5-element Takumar should be capable of great results, but I wasn’t prepared for what I saw when I pulled the strip of film from my Paterson tank.

For starters, the Heliar based Takumar delivered the goods in sharpness and contrast. The deep blue color coating of the lens is a refreshing change from the yellowed coatings more commonly seen on most M42 Takumars of the era, and produced some wildly vivid colors. Reds and blues were excellent as seen in the flag pic and the one of the toy car.

Shooting an ASA50 speed film on a camera with a 1/50 shutter speed, I didn’t expect much from the two interior shots I took of the Budweiser neon sign and the restaurant workers, but they came out great. Not that I had any reason to doubt it, but the Takumar lives up to its reputation as a world class lens that is as good as anything on the market, then and now.

The camera itself was a pleasure to shoot as well. Without a pentaprism, the camera is very short from top to bottom and had it not been for the length of the lens, I could have easily fit it into my pants pocket. The focus and aperture rings on the lens were smooth and nicely dampened, and the film advance and film transport felt like the camera was brand new,

The waist level finder was as good as any I’ve used on any other 35mm camera, and was easy to compose with in all but the dimmest light. This is especially impressive considering the slow-ish f/2.4 speed of the lens. The Asahiflex is one of only a few SLRs ever made with an optical viewfinder, so for fast action shots, you can get an approximation of your image using the one built into the body.

Perhaps the most impressive thing about the Asahiflex is how much Asahi got right with their first camera. Build quality is on par with German Leicas and Nikon rangefinders, the ergonomics are as good as, and perhaps even slightly exceed those from the KW Praktiflex/Praktica, and of course the Takumar lenses are are good as anything made by Zeiss or Leitz. It is clear that Asahi Optical got off to an excellent start and never looked back. The Asahiflex received several incremental updates in its short life span, before being replaced by the Pentax in 1957, and the rest was history.

The Asahiflex has the rare distinction of being beautiful to look at, beautiful to use, makes beautiful images, and is historically significant. There is nothing to not like about this camera, and one that even after returning it to its owner, will be one that I hope to add to my permanent collection some day.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Asahiflex

http://mattsclassiccameras.com/slr/asahiflex-iia/

https://www.pentaxforums.com/camerareviews/asahiflex-iia.html

Fantastic article, as usual. I recently sold a Tower 22 and loved the size and workmanship of the camera.

Nothing wrong with that lens, is there, Mike, and vintage mid-50’s design to boot. That film looks interesting, too.

An impressive write-up of an historical model.

The 58mm f/2.4 Takumar has the distinction of being the only 35mm SLR standard lens that was designed around the Heliar type (five elements in three groups) prior to 2001.

Eric Hendrickson at http://www.pentaxs.com in TN repairs Asahiflex cameras, along with most all 35mm SLR and medium format Asahi products. And he does a first class job at it. Eric is IMHO the Chris Sherlock of Asahi!

Nice camera! I am going to buy Asahiflex iia or Tower 22. May I get suggestion that which one has more value? They have same lense.

Id say the Asahiflex and Tower branded cameras have the same value. The bigger differentiator is the condition of the body and which lens it has. If everything else is the same, just buy whichever one you can find cheaper.

Thank you! Have a nice day 🙂

I just got Asahiflex ‘I’ instead 🙂

Hi.

Intersting post, and very impreesive results from the camera.

I own a few versions, and was recently given one with some issue to attempt a repair. Unfortunately there a few things Asahi didn’t get right, despite the good quality of the engineering .The camera I was working on had a blind shaft that had come out of its bottom bearing hole, and it turned out the blind tension spring is only locked in place by a bit of bent wire across some cuts in the top of the shaft. Worse still, that same piece of wire has to push the shaft downwards, because otherwise it will pop out of its hold again! For some reason Asahi didn’t step the shaft so it could not move upwards, and consequently it has a tendancy to come out of its locating hole in the base.

Plus the wind-on uses some very odd solutions to lock and release the shutter, which over time fail to work because of wear and in this instance a broken washer that jammed the release of the gears.

Compared with the more complex, but better designed , mechanics of later cameras there is no comparison. But when they work, they are little jewels!