This is a Canon 7, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Canon starting in September 1961. The Canon 7 would be the last new model to use the Leica Thread Mount which they had been using since the release of the Canon S-II in 1946. Canon took a big risk releasing the Canon 7 as it came after nearly every other Japanese camera maker, including Canon, had already starting producing a 35mm SLR model. To help compel buyers to still consider a rangefinder camera, they offered several upgrades never before seen on any Canon rangefinder model such as an exposure meter, switchable visible frame lines, and a secondary bayonet mount for the Canon f/0.95 “Dream” lens. The age of the reflex camera had already started when the 7 was released, yet it still managed to become Canon’s best selling rangefinder camera and a popular collector’s item today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 Canon Lens coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: M39 Screw Mount and external Canon “Dream Lens” Bayonet

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder w/ Adjustable 35mm – 135mm Frame Lines and Automatic Parallax Correction

Shutter: Metal Foil Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate read out

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync, if hotshoe, flash sync speed

Weight: 893 grams (w/ lens), 620 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/rl/00038/00038.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Canon 7 was the end of the line for the Leica Screw Mount rangefinder which made it’s debut in 1931. Other than using the same film and having a compatible lens mount, the two camera share nothing in common. Canon improved the formula in every conceivable way, making the ultimate camera. What Canon accomplished back in 1961 when the Canon 7 was released is nothing short of extraordinary, an accomplishment that translates into an excellent camera that holds up well today. The Canon 7 is nearly perfect, with only a few minor issues like a missing accessory shoe and a meter that is almost found in non-working condition today. But don’t let that dissuade you from trying one out, as this is one of best cameras ever made. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall excellence, the complete package | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.2 | ||||||

History

Over the last four decades or so, it has been easy to see Nikon and Canon as equal competitors at the top of the photographic world, each releasing some of the best cameras and lenses any company could offer. If you were a professional photographer, buying either a Nikon or a Canon was a good choice as the quality and selection of bodies, lenses, and accessories for each system was immense.

Over the last four decades or so, it has been easy to see Nikon and Canon as equal competitors at the top of the photographic world, each releasing some of the best cameras and lenses any company could offer. If you were a professional photographer, buying either a Nikon or a Canon was a good choice as the quality and selection of bodies, lenses, and accessories for each system was immense.

It wasn’t always that way however. I’ve written quite a lot about how Nikon, then called Nippon Kogaku got started making cameras and lenses after the war, but even though Nikon is the older of the two companies, it was Canon that first started making consumer cameras and lenses. In the 1930s, Canon, like many small optics companies of the day started out by making copies of the Leica rangefinder. When their first model was ready to go on sale in 1936, the Hansa (or Standard) Canon shared a lot in common with it’s German inspiration.

The original Hansa Canons did not use the 39mm Leica Thread Mount, instead opting for a complicated bayonet mount designed and built by Nippon Kogaku. After World War II when it became necessary for Canon start producing cameras to help rebuild Japan’s economy, they opted for the Leica’s simpler, less expensive, and more reliable screw mount which at the time they called the “Universal Mount”. Canon’s first camera to have this mount was called the Canon S-II in 1946.

Canon was not content to simply make a copy of the Leica and call it a day. From the moment they announced their first prototype in the 1930s, all the way through their post war models, Canon took the best parts of the Leica and improved upon them. Instead of separate windows for the viewfinder and rangefinder, Canon went with a combined coincident image viewfinder. To accommodate lenses with focal lengths other than 50mm, Canon deployed a clever adjustable viewfinder which used a rotating prism that depending on how it was turned, could show one of three different focal lengths.

In the first few years after the war, Canon, like most other Japanese companies struggled to get their products into the hands of western photographers. Japanese made products weren’t known to be of high quality, and even if they were, it was difficult for Americans to put trust in something made by people who only a couple years earlier were at war with them.

Eventually however, Japanese products by Canon, Nippon Kogaku and other companies started to win over the west. Japanese cameras were no longer cheap knock offs, they were seen as viable competitors to quality cameras and lenses made in Germany.

Although Canon’s rangefinders were clearly based off the Leica III, they were often sold at a discount as lower cost alternatives to German cameras. It was Nippon Kogaku who went head to head with the best that Germany had to offer. With models like the Nikon S2 and later the SP, Nippon Kogaku strove to attract the buying dollar of the world’s top professional photographers.

After Leitz released the Leica M3 in December 1953, the leadership at Nippon Kogaku saw that the writing was on the wall for professional rangefinders. The Leica M3 took Japan and the rest of the world by complete surprise and Nippon Kogaku’s head of design, Masahiko Fuketa realized that there wasn’t a whole lot more that could be done to continue improving upon existing rangefinder models. In 1955, as they worked on what would become the Nikon SP, Nippon Kogaku made the bold decision to develop alongside the SP an all new Single Lens Reflex camera.

The SLR was not new in 1955, as 35mm reflex cameras existed since the 1930s, however these early designs had several cons that prevented them from widespread adoption by the pros. Things were changing though as pentaprism viewfinders, instant return mirrors, and more reliable shutters improved their appeal.

Japanese companies like Asahi Optical and Miranda were the first to market with a Japanese SLR and Fuketa knew that if Nippon Kogaku was to stay competitive in the professional market, they’d need a model too.

Perhaps due to strong relationships Nippon Kogaku developed with American photographers like David Douglas Duncan, Horace Bristol, and Carl Mydans, Nippon Kogaku always had the ear of professional American photographers stationed in Japan. Fuketa intently listened to what the pros wanted in their cameras, and with his new reflex camera still in development, a great deal of feedback went into creating it’s features.

Canon on the other hand, was doing quite well with their screw mount rangefinders. At the same time the Nikon S2 was hitting the market, Canon was readying their V-series cameras which were a dramatic upgrade from the earlier models. Significant changes to the V-series from all previous Canons were all new bodies with back loading film compartments, self-timers, larger viewfinders, and later models with metal foil shutters and top mounted film advance levers or those with bottom trigger advances.

Canon was not unaware of the looming rise of the SLR, but it seems they did not value as much input from the pros when they created what would become the Canonflex SLR in 1959.

When it was released, the Canonflex was a nice camera with excellent build quality, a good shutter, and interchangeable viewfinders, but it had a clunky breech lock lens mount, lacked any sort of motor drive coupling, any provision for metered viewfinder, it relied on a bottom trigger film advance that made mounting to a tripod very difficult, and upon it’s release had a poor selection of lenses available.

The Canonflex was a failure and was not produced for very long, eventually being replaced by mid-tier SLRs in the early 1960s. All was not lost however as Canon’s sales of rangefinder cameras was quite strong. Although the pros were abandoning their rangefinders in favor of SLRs quickly, sales were still strong in other markets.

Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, no one could compete in the pro market with Nippon Kogaku, so most companies didn’t even try. In order to keep up with immense demand for the Nikon F, Nippon Kogaku abandoned rangefinder development, creating a huge opportunity for companies like Canon to keep innovating and releasing new models.

When it was released in December 1958, the Canon P was the last of an almost constant release cycle of new Canon rangefinder cameras. From their early postwar S-II up to the P, 33 different Canon models were released with confusing model numbers that seemed to jump back and forth between II, III, IV, V, and VI models. Some with features that came before others without them, and some seeming to be identical to earlier models just with a different name. Canon’s development cycle never ended and until 1958, never stopped to take a breath and come up with an all new model.

For Canon’s next rangefinder, and their first new model after the release of their failed Canonflex SLR, the company took things much slower, handing over the design to Masamichi Kakunodate, allowing the design and construction to come together over time. The new camera, now called the Canon 7 would not be released until June 1961. Included in it’s feature set was every feature Canon thought a rangefinder user could want, with the notable exception of an accessory shoe.

The Canon 7 was a very large and heavy camera, more than 350 grams heavier than the original Canons from the 1930s, but with the increased size came a long list of features such as a coupled selenium exposure meter, a large and bright viewfinder with five different adjustable frame lines, a metal foil focal plane shutter with speeds from 1 to 1/1000 second, and a new external bayonet lens mount.

For the first time in a Canon rangefinder, the viewfinder used projected frame lines instead of a rotating prism. This allowed for focal lengths of 35mm, 50mm, 135mm, and both 80mm and 100mm to be shown. In order to accomplish this, magnification was reduced to about 80%, down from the Canon P’s near 100% view. To compensate for the loss of magnification, the rangefinder base length was increased by 50% from previous Canon rangefinders to 59mm.

The exposure meter was large and much more accurate than others found on cameras of the day. It featured a high and low sensitivity mode, selectable by an unlabeled wheel on the back of the camera. Using the Canon 7’s meter was very easy as a curved display would indicate the exact f/stop needed to make a proper exposure. There were no complicated EV or LV numbers to contend with like on other metered cameras.

The shutter used the same metal foil curtains of earlier models, but internally it was reworked to be more reliable, quieter, and also to add a T mode which was missing on the Canon P and all VI models. The shutter on the Canon 7 was said to be nearly identical to the one used on the Canonflex SLR and Canon’s early SLRs, except the SLRs all had cloth shutters instead of the metal foil like on their rangefinders. The reason for this is to prevent pinholes being burned into the cloth material if the camera is exposed to direct sunlight with the lens set to infinity. On cloth shutter rangefinders, when this happens, the lens acts as a magnifying glass on the sunlight and can actually burn holes in the cloth material. On an SLR, the reflex mirror prevents this from happening so using metal foil wasn’t necessary.

The shutter used the same metal foil curtains of earlier models, but internally it was reworked to be more reliable, quieter, and also to add a T mode which was missing on the Canon P and all VI models. The shutter on the Canon 7 was said to be nearly identical to the one used on the Canonflex SLR and Canon’s early SLRs, except the SLRs all had cloth shutters instead of the metal foil like on their rangefinders. The reason for this is to prevent pinholes being burned into the cloth material if the camera is exposed to direct sunlight with the lens set to infinity. On cloth shutter rangefinders, when this happens, the lens acts as a magnifying glass on the sunlight and can actually burn holes in the cloth material. On an SLR, the reflex mirror prevents this from happening so using metal foil wasn’t necessary.

Although still supporting the original 39mm Leica Thread Mount, the Canon 7 added a second bayonet lens mount around the outer perimeter of the screw mount for an all new 7-element f/0.95 lens. Weighing in at over 600 grams, the new lens was massive, blocking out nearly a quarter of the view through the 50mm frame lines in the viewfinder.

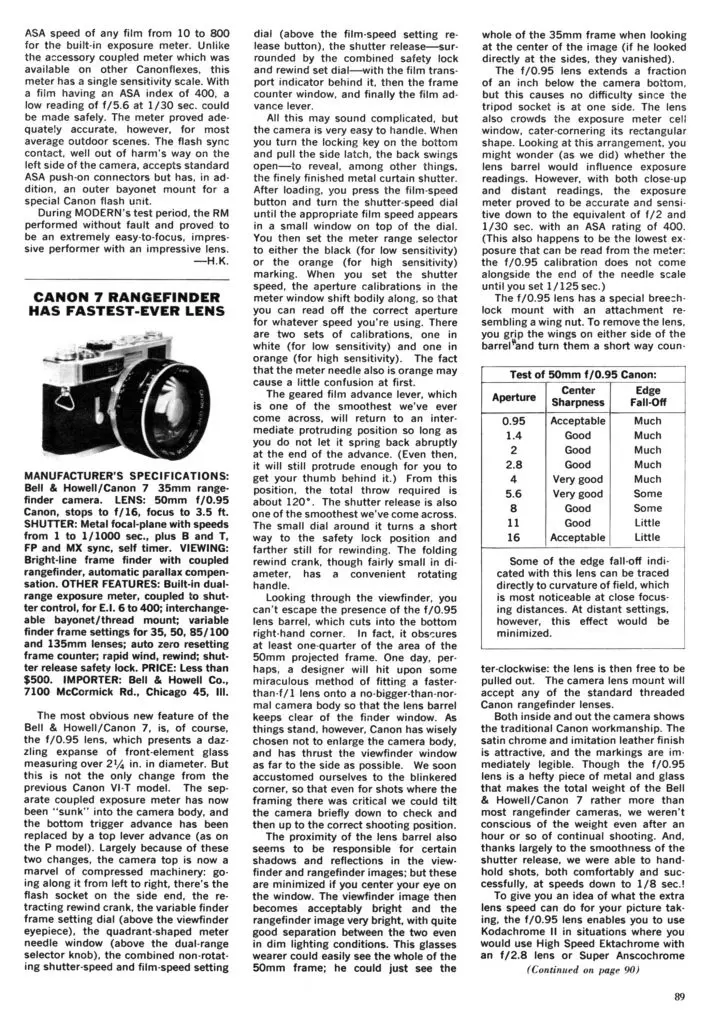

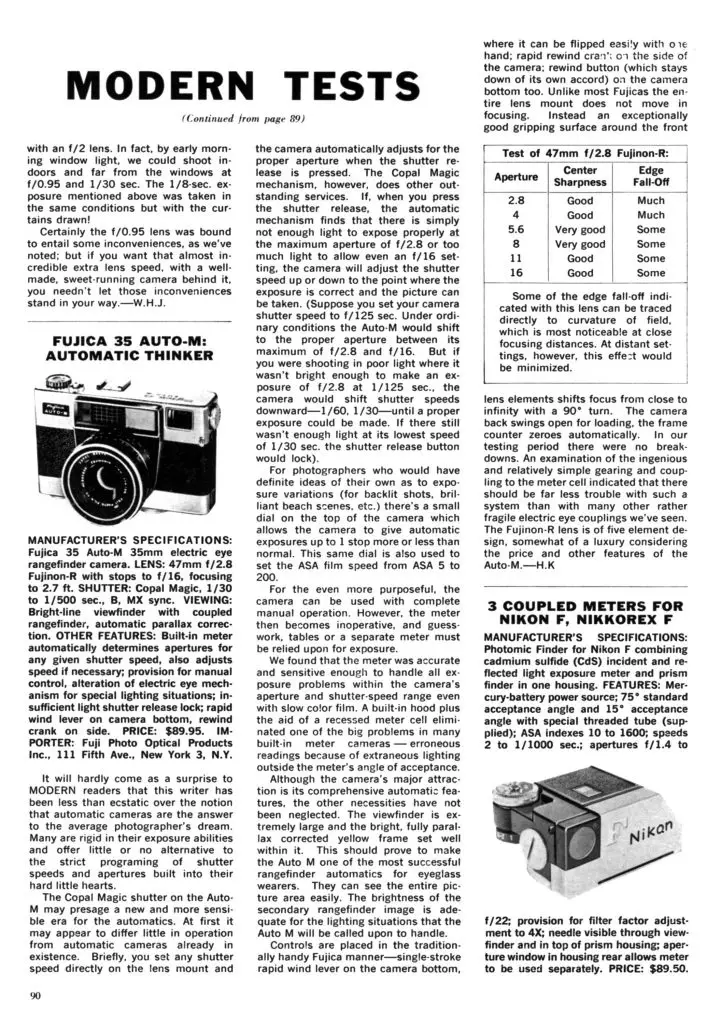

The f/0.95 lens was nicknamed a “Dream Lens” by the British press, a name which it continues to be referred to by today. It had a look that was extremely soft wide open and suffered from significant field curvature. In a short Canon 50mm lens test from the April/May 1968 issue of Camera 35, it never attained a center sharpness higher than 56 which is quite low.

The Dream Lens also flared like crazy if any sources of light were near the front glass element. Despite these optical imperfections, it was the fastest regular production rangefinder lens ever made and was highly sought after. Shortly after it’s release some lenses were adapted to other mounts such as the Leica M-mount as there was no lens with comparable specs for that system. Along with a new Canon Mirror Box 2 reflex attachment that also used the bayonet mount, no other lenses or accessories were created for the bayonet.

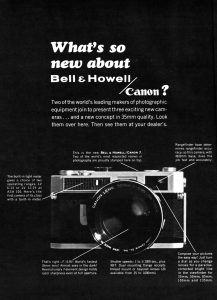

The Canon 7 was sold worldwide, but through Canon’s exclusive distribution channels in the United States, the camera was co-branded as the Bell & Howell/Canon 7. It carried a retail price of $200 body only, or from $289.95 to $499.95 when equipped with a range of lenses from the 50mm f/1.8 to the 50mm f/0.95 lens. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $1729, $2500, and $4325 respectively today.

Despite not being a camera designed for the professional photographer in mind, the Canon 7 was not cheap. It’s price with the f/1.8 lens was on par with SLRs like the Canonflex RM and Minolta SR-7 at $299.95 and $270 respectively, and only a little cheaper than the Nikon F at $329.50.

It would seem that Canon’s efforts to continue investing in high quality rangefinder cameras paid off, as the Canon 7 was extremely successful, outselling all previous Canon rangefinders by a wide margin. According to Peter Dechert’s Canon Rangefinder book, 137,250 cameras were sold between June 1962 and November 1964.

The Canon 7 was so successful that Canon revised the model twice, once with a name change and once without. The first revision came in February 1965 and was called the Canon 7s. Addressing one of the few omissions to the original 7’s feature set was the re-addition of an accessory shoe. This necessitated a change to the meter readout display, being slightly smaller and more rectangular.

The biggest change however, was the new CdS exposure meter, replacing the dated selenium meter. At a quick glance, the Canon 7s is easily distinguished by it’s round meter window in place of the large rectangular window on the earlier model. The addition of a CdS meter meant that for the first time, a battery was a needed in a Canon rangefinder camera. To make space for the type 625 mercury battery inside the camera’s base plate, the tripod socket had to be relocated to an offset position near the door key. One final change was to the small meter sensitivity switch on the back of the camera, which was now a meter on/off switch. A ring around the front meter window allowed the selection of high and low sensitivity modes.

Finally, around August 1967, the Canon 7s received one final update which was not given a new name, but has unofficially become known as the Canon 7sZ as the letter “Z” indicates the last of the line. The only change made to this model was an updated viewfinder that reduced ghost images and improved the view for people with nearsightedness. The easiest way to identify the 7sZ from a 7s is to look for the location of the rangefinder adjustment port. On the 7s, this port is next to the shutter speed dial, above the rangefinder window, and on the 7sZ it is above the second letter “n” in “Canon”. It is worth noting that some sites online incorrectly suggest another change to the 7sZ was a larger rewind knob, and while it is true that the 7sZ does have a larger knob, this was actually a mid-model change to the 7s, and not unique to the 7sZ.

The final Canon 7-series models were produced in September 1968, making them the longest lived Canon camera until that point. If you group all Canon 7-series cameras together, sales topped 157,000 units, which exceeds the total number of all Nikon rangefinder cameras by nearly 20,000. Quite an impressive feat considering this was a model that was being sold parallel with a huge number of competing SLRs.

Today, all Canon rangefinders are collectible, including the Canon 7. Considering the large number of them made, they’re not that hard to find today, and as a result, prices for them are extremely reasonable. You can easily find Canon 7 bodies online for around $100 or sometimes less. With a lens, in good condition, samples can be had from between $150 to $200, which is an incredible bargain considering what you are getting, making them one of the best rangefinder values of any camera by any company, ever made.

My Thoughts

I was well aware of the Canon 7’s excellence through reading about them on many blogs and researching the camera myself several times over the years, but for one reason or another, this was a model that eluded me for quite some time until I picked one up from site reader Bob Houlihan who also sold me my Tower 45 in the fall of 2019.

The Canon 7, as literally every site online suggests, is a wonderful full size rangefinder camera with nearly every feature you would want on a camera of this era. It is definitely larger and heavier than the onslaught of compact rangefinders that would hit the market in the late 1960s and into the 70s, so if you have small hands, or are sensitive to heavy pieces of metal, this might not be the camera for you.

For everyone else, the controls on the Canon 7 are nicely laid out and work well for people with average to large hands. The top plate is a bit cluttered and reveals the cameras biggest omission, which is the lack of an accessory shoe, as was available on the Canon 7’s predecessor, the Canon P.

Also missing from the Canon P is the neat, recessed rewind knob, instead replaced by a more traditional pop up knob with fold out handle. A larger diameter knob would start to appear on the later Canon 7s midway through it’s production, but the one here is of sufficient size and works fine.

Next is a dial for selecting different frame lines within the viewfinder. This dial has four different positions, allowing you to select 35, 50, 85/100, and 135. Although changeable focal lengths have been a common feature in Canon rangefinders all the way back to the IIB from 1949, they all used a rotating prism that optically changed the light as it passed through the viewfinder. The Canon 7 was the first model with changeable projected frame lines that showed different focal lengths.

The viewfinder is extremely bright and contrasty. The main viewfinder image has a subtle blue tint which contrasts nicely with the pale yellow tint of the rectangular rangefinder patch and projected frame lines. In the gallery below, you can see what all four combinations of frame lines look like. Both 85mm and 100mm frame lines are shown together as both are very similar. Finally, note that in the 135mm frame line images, the field of view is narrower than the other three, but that’s because I had to hold my cell phone farther away from the camera to get the 135mm lines to show up properly. This is not how it looks in person. All of the frame lines, regardless of focal length, are automatically corrected for parallax.

Back to the top plate, in the center where an accessory shoe appears on the later 7s is the meter scale from the coupled selenium meter up front. Although I am generally not a fan of top plate meter read outs as I find that they slow me down, the one on the Canon 7 is the best I’ve ever seen.

The meter is coupled to the combined shutter and film speed dial next to it. As you select different speeds the f/stop scale changes. Two different sets of f/stops are displayed, some in white and others in orange. These sets correspond to the high/low sensitivity dial on the back of the camera, indicated with a black and orange notch. With the black notch selected, you use the white numbers, and with the orange notch selected, you use the orange numbers.

With the camera pointed at your subject, the orange needle farthest from the shutter speed dial will point to one of several zebra stripes which act as pointers to an appropriate f/stop for the chosen shutter and film speed you have set. Using the example above, with the shutter speed set to 1/125 and film speed of ASA 100, the camera is recommending an f/stop of f/2 if the meter was in high sensitivity mode, or f/16 in low sensitivity. It’s not as simple as a camera with auto exposure would be, but for a fully manual selenium metered camera, this was as easy as it got!

Next to the shutter speed dial is the cable threaded shutter release with three position collar around it. The letters “A” and “R” indicate normal film advance and rewind, and a red dot is for a locked position in which the shutter release cannot be depressed, even if it is cocked. Below the A/R collar is a small circle with a red dot that spins as film is transported through the camera.

The film advance lever is sufficiently long and has a full throw of less than 180 degrees from closed to fully cocked position. The lever has a combination of just the right amount of resistance with extremely smooth travel, making for a very pleasant and fast motion. When shooting, the lever can be left out about 30 degrees into a ready position making for an even shorter throw for the next exposure. Finally, between the shutter release and advance lever is the automatic resetting exposure counter.

The back of the Canon 7 shows the large opening for the viewfinder along with the high/low dial for the exposure meter. To the left of the Made in Japan engraving is a small, unlabeled button that when pressed, allows you to change the ASA film speed setting on the shutter speed dial.

The bottom of the camera is pretty sparse, with only the 1/4″ tripod socket on one side, and the door release key on the other.

Like the Canon P and earlier Canon rangefinders, the Canon 7 has a double film door lock, in which the bottom “Leica style” lock controls a metal tab that sticks out of the side of the camera, beneath the door latch. This prevents the camera from being opened accidentally while film is in the camera. In order to open the camera, you must first release the bottom lock, and then pull down on the release latch on the camera’s left side.

The most striking thing about the Canon 7’s film compartment is the smooth metal foil shutter. Contrary to popular belief, Canon’s reason for using a metal foil shutter was not because it was faster, or weighed less, but it was to make it impervious to pin hole light leaks that were common with rangefinder cameras when left out in sunlight.

Because there is no obstruction between the lens and the shutter on a focal plane rangefinder, if you leave the lens at infinity in direct sunlight, the lens acts as a magnifying glass on the sun, which can quickly burn a hole in cloth shutters. With the metal foil shutter, this is not likely to happen.

Otherwise, the film compartment is pretty typical, with left to right film transport onto a fixed, single slotted take up spool. The film door has a smooth metal pressure plate and a metal roller to maintain flatness and resist friction as film transports through the camera.

Up front, there is the large faceted window covering the selenium light meter with integrated rangefinder window. To it’s right is the frame line illuminator window for the viewfinder, and then the main viewfinder window.

On the main body is the mechanical self timer and screw lens mount. Like all Leica Thread Mount cameras, the lens is removed by rotating counterclockwise and installed by rotating clockwise. The Canon 7 is rangefinder coupled on lenses only down to 3.5 feet. You can use lenses with a closer minimum focus such as the Nikkor-HC 5cm f/2 lens, but the rangefinder will disengage at distances less than 3.5 feet.

The lens mounted to my Canon 7 is not period correct for this model as Canon 7’s would have come with a later style lens with a black focus ring and lighter weight alloy body. The lens I have mounted is the earlier all brass and chrome Canon 50mm f/1.8 lens produced from 1952 to 1955. Although optically the same, this version of the Canon 50/1.8 would have been the standard lens on the Canon IV Sb.

It doesn’t take long after first picking up the Canon 7 to be inspired by it’s excellent build quality. This is a camera whose first impression is of quality, and one that before you see a single image from it, you expect to deliver outstanding results. But did it?

My Results

I knew I needed to give the Canon 7 a thorough look using more than one roll of film. I figured, it’s taken me 3 years to finally review this camera, I might as well spend more time with it than I do for most reviews. For the first roll of film, I used one of three rolls of frozen Kodak Portra 160 VC that I inherited from my neighbor after he passed away.

I am very familiar with Kodak Portra 160 as it’s one of my favorite films, but until now, I’ve always shot the NC, or Neutral Color versions of the film. I had never tried the VC or Vivid Color version. Although expired by at least 15 years, my neighbor’s widow assured me this film has never left her freezer since the day it was purchased. How would 15 year frozen Portra VC compare to fresh Portra NC? Would the colors actually be more vivid, and would Portra still retain it’s good latitude that I’m used to?

I think the answer to that question is a resounding yes. The Portra 160 VC is much more vivid than the NC versions, producing a color palette closer to Kodak Ektra, just without the over saturation that film sometimes produces. The sharpness, small grain, and color saturation of this film is simply stunning, and makes me wish I had more of it.

Several years back when I bought my Canon P, I remember obsessing over whether to buy the P or the 7, and I recall reading several people’s opinions that the Canon 7 was somehow built to a lower quality standard. That by the time of it’s introduction, Canon had started using more light weight materials that perhaps wouldn’t hold up over time.

Now that I have the luxury of owning both models, I can tell you that’s a ridiculous statement. Perhaps an experienced camera repair technician can spot some internal differences between the two, but from a purely tactile standpoint, both the Canon P and 7 are extremely high quality and well built cameras. On a scale, the Canon 7 is 55 grams heavier than the Canon P, likely due to the metering circuitry and more complex viewfinder, but there’s definitely no obvious weight saving or quality reducing parts to be seen.

That’s not to say the Canon 7 is universally better than the P, as both cameras have their own merits. The Canon 7’s viewfinder is more advanced with selectable frame lines, but this feature does not automatically make it better. If you only ever shoot 50mm lenses, then being able to choose different focal lengths will not appeal to you. The presence of all frame lines in the Canon P is a bit cluttered, but with 100% magnification, the Canon P is easier to shoot with both eyes open.

The Canon P lacks an exposure meter, but considering the rate at which selenium meters fail, most people should not expect to find a Canon 7 with a working meter these days, so the lack of one on the P isn’t much of a con. Plus, the slightly cleaner lines of the P is objectively more attractive to my eyes. But for anyone to say that the Canon 7 is a cheap camera, clearly has never used one before.

I won’t even suggest that the availability of the f/0.95 “Dream” lens should be much of a deciding factor as that lens is rare and incredibly expensive. A quick eBay search of sold auctions results in prices ranging from $1500, all the way up to $4100 for the lens by itself, meaning that if this is a lens that’s in your budget, you likely don’t need buying advice from me.

If you’re interested in seeing some examples of what this lens can do, check out the Flickr gallery below, filled with over four thousand examples.

Even without the f/0.95 lens, the Canon 7 is a very capable tool with any of Canon’s excellent screw mount lenses. If you don’t have any Canon lenses, any number of Japanese, German, or Soviet rangefinder lenses will work as well.

My example with an earlier f/1.8 lens delivered superb results with excellent sharpness and contrast across the entire frame. Using both color and black and white films, I got excellent results without any optical anomalies often associated in lesser lenses.

When wearing the all brass Canon lens, the large Canon 7 body weighs in at a hefty 893 grams (1.96 lbs) which is SLR territory for most cameras. A good neck or wrist strap would be an essential accessory for anyone wanting to carry this camera on an all day trip.

With the extra weight however comes confidence, this is a solid piece of craftsmanship that never gives a hint of cost cutting. If you cannot get good images from this camera, the problem is most likely you.

This exact camera and lens combination is the same one I loaned out to Alyssa from Aly’s Vintage Camera Alley, and like the Canon P was to me, this was Aly’s first experience with an interchangeable lens Canon rangefinder, and one that she came away from loving. In fact, her love for this camera has been a bit of a curse for her as now she is longing for a nice example with a working meter and lens of her own. You can find Canon 7 bodies with dead meters easily, but one with a good meter and lens costs considerably more.

I started out this section reminiscing back when I first bought my Canon P thinking that it was the better of the two, and now that I’ve had the pleasure of owning and shooting both, I can say that whatever heartache I might have experienced trying to decide between the two, no matter which one I would have bought, I would have been happy with as both the Canon P and Canon 7 are 100% worthy of their reputations as two of the best screw mount rangefinders ever made.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Canon_7

https://www.cameraquest.com/canon7sz.htm

https://alysvintagecameraalley.com/2020/09/07/the-canon-7-rangefinder/

https://www.35mmc.com/17/03/2018/canon-7-review/

https://casualphotophile.com/2020/11/02/canon-7/

https://global.canon/en/c-museum/product/film42.html

https://shootfilmridesteel.com/the-canon-7-rangefinder-best-bargain-ive-found-in-ltm/

https://emulsive.org/reviews/camera-reviews/camera-review-canon-7-rangefinder-by-andrew-macgregor

I have a Canon 7 and love it. People obsess over the Barnack Leicas, but the Canon P and 7 are in my opinion, superior in having really good viewfinders, better controls, metal shutters, and none of that bottom-loading foolishness. Considering the price for a Canon 7 vs a Leica IIIg, it’s easy to see which one is more affordable. Leica’s M-mount series are another matter, but the Canon P is certainly on par with them.

Nice review and history!

Mark

Thanks for the feedback Mark. I agree with you, Leica hysteria has likely caused a great number of people to completely dismiss these cameras. Don’t get me wrong, I am very fond of both screw and M-mount Leicas too, but that’s not to say that one is universally better than the other. Plus, with prices today, when I can’t make up my mind which one I want to use, I just use both!

I have a Canon 7 and use it with the Canon 135mm f:4 lens. I do have the 50mm 1:1.8 standard lens as well. This is a wonderful camera in spite of it’s weight. At times, I am in the mood to use range finder cameras. What I do is set up my Canon, the Leica IIIc with the Summitar 5cm 1.2 or Simlar 5cm 1.5 and the Leotax F with my Topcor 3.5cm f:3.5. Then with my daughter or grand-daughter we venture out on the days photo safari. The next event may be with TLR’s or SLR’s based on the mood or weather conditions. Film is not dead. We use both 35mm and 120mm film formats.

Note: the Canon 7 is not ususally my first choice, it is a heavy camera which may be it’s only negative…however the Yashica Electro 35 with a “Telephoto” add-on may be more difficult to handle, it is very lens heavy. I stow a tripod in the truck just in case. David C.

I do have a wide angle Serenar lens that I could use on this camera, but sadly, it has some pretty bad internal haze. I generally love wide angle lenses on rangefinders though and would love to get a better one for my Canon 7 for the very reasons you state.

I loved your review Mike! It reminded me of the pristine Canon VI-T with 50mm/1.2 lens I bought for $10 at a yard sale a couple decades ago. I’ve read in several places that its base-plate winding lever is a “sturdy and reliable” mechanism, but in my unit, it sporadically loses its grip on whatever advances the film within the camera. The winding lever then slides back and forth uselessly, but always seems to “reset” itself if I just let it sit unused for awhile. I do NOT understand that (but then again, my condo unit DOES happen to be haunted)!

Still, I’m keeping the camera for a couple reasons:

The lens works marvelously when adapted to my Fuji X-Pro1.

And an old sticker inside the VI-T’s film chamber reveals that it had been purchased in the “Suga Camera Shop, Imperial Hotel Tokyo.”

So what’s so great about that? I’m a huge fan of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture, and he redesigned and rebuilt the original Imperial Hotel in several stages beginning in 1919. The architectural tricks he used helped the hotel survive Tokyo’s devastating 1923 earthquake almost without damage. But he didn’t adequately anticipate that it could sink unevenly into the site’s alluvial mud… some parts slipping down into the water table by a whopping 43 inches! And Wright’s beautiful structure suffered further damage during World War II. So his hotel was demolished in 1967 and rebuilt in today’s high-rise form. (However, Wright’s original central lobby and reflecting pool were disassembled and rebuilt at Tokyo’s Museum Meiji-mura, where the public can experience at least a bit of the hotel’s lost majesty.)

But according to Wikipedia, 8,175 Canon VI-Ts were sold from June 1958 to July 1960, which means that mine wasmost probably purchased in Wright’s building. I’ve visited the architect’s Fallingwater and nearby Kentuck Knob, but cannot tour his Imperial Hotel. So my VI-T is as close as I’ll ever get!

Great story, Dave and thanks for the feedback on the review. Frank Llloyd Wright designed a bunch of houses and other buildings near where I live. There was one strange looking house he did in Flossmoor, Illinois that I would pass every day on my way to school as a kid. I always thought it was ugly, but beauty is in the eye of the beholder!

You sent me on a research quest, Mike! That “Frederick D. Nichols House” looks like it was built during Wright’s transition period toward his later Prairie Style. According to Thomas O’Gorman’s “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Chicago,” the town of Flossmore’s Scottish name means “gently rolling countryside.” And the house wasn’t initially built as a four-season home. It was a “summer golf hideaway” without heating or electricity. A rather BIG hideaway at that… with a rustic redwood-plank exterior. It appears to fit much better into the neighborhood now!

In your one reply, you’ve managed to educate me more on that house than I’ve learned in my entire life, driving past that house thousands of times! It’s also interesting to know that Flossmoor means “gently rolling countryside”, most people think it was founded by dentists that wanted people to floss more! 🙂

LOL… Very glad to help!

I had one last year and although it was everything I expected in terms of features and I could find no fault with it I just didn’t feel like it was the camera for me; I don’t know why.

It happens! There have been many cameras that were very highly regarded by other people that just didn’t connect with me too. The great news is that there are a ton of other options to find the one that’s perfect for you!

Another of your incisive and informative reviews, Mike. I’ve only one teensy weensy piece of info that may be of interest to users who develop their own film. The film winding confirmation works directly off the sprocket shaft, and in film rewinding mode the little indicator stops revolving the moment the film leader leaves the sprocket shaft. Helpful when film cassettes are used where it’s difficult to remove the cap as it leaves some of the leader showing.

I worked for Canon in the 1970s repairing cameras then had my own repair shop for a few years into the early 80s. I’ve worked on a lot of Canon rangefinders and Leicas over the years. Personally I prefer the shutter design of the late Canon RF’s over the Leica. It is a much more elegant design, at least from a repair point of view. And just as well made as the Leica. I think Leica’s viewfinders have an edge on the Canons but for the price difference that’s ok. The Canon 7 is a true bargain. Pair it with Canon’s excellent 50mm 1.4 and you’ll be a very happy shooter! All the Canon RFs from the 5 series on were beautifully made cameras that were a pleasure to use.

Thanks! Excellent article! As usual. I had a 7 for a few years and really liked. It is indeed a very good camera.

I can’t tell you how much I love reading these great, detailed reviews. I just received a nice Canon 7 with a working meter this week, along with a Canon 35mm f/2 lens. It even came with the hard-to-find accessory coupler which gives it a cold shoe (although with the working meter and as someone who never uses flash, I’ll likely sell the coupler). I also have a P, a VI-T, and a 7sZ, and to this point the P has been my favorite. But who knows, maybe the 7 will overtake them.

Andrew, thanks for the positive comments! I appreciate hearing from my readers probably as much as you like reading my reviews! Of course when there’s something as nice as the Canon 7, it makes my job easier. I have many cool reviews planned for 2021 that I hope you continue to enjoy. Don’t forget to subscribe! 🙂

I find the old Canon 7 simply indestructible. The ghost images around the rangefinder patch are annoying but small price to pay for such a bargain. Plus you never have to worry about burning a hole in the metal shutter.

I purchased a Canon 7 from KEH in the Atlanta area in November of 2023. I’d wanted to try a rangefinder camera for many years, but never had one. I’ve mostly shot Canon all my life, and love their products. I was thinking about a Canonette, then found out about their copies of the original Leicas. The P, and 7 had caught my eye. I saw the one on KEH’s website, put it on my wish list, and was able to purchase it out of my next paycheck. A few weeks latter I was able to purchase an all chrome 50mm f/ 1.8 Canon L39 lens, also from KEH.

I have not shot a full roll of film through the camera yet, though I really need to. I did use the lens adapted to my Canon R7 a few weeks ago, and just edited the photos yesterday. I was really happy the way they turned out. A couple I might have missed focus on a little when shooting at f/ 2.8 or below, or I focused, recomposed, and didn’t take that into account with the shallow depth of field. But I will get better with manually focusing the len both with the rangefinder patch on the Canon &, and the focus peaking on the R7.

I’m hoping to be able to get at least a fast 35mm, and 85mm to use with it. I think it might make for some fine portraits, and landscapes maybe? Love to run to HP5 though it. I have some TMax, the HP5, and I think 1 more roll of CineStill XX I could run through it. The CineStill might go in one of my FD cameras, or the Elan 7e though.

Great article! I look forward to reading more, and love the Podcast!!

You’ll love the Canon 7, it is a great camera to shoot. You already know the lens is good, so the images will look just as good on film. As for fast wide and tele lenses. Canon made both f/1.8 and f/2 lenses in 35mm which would work great. Despite the f/1.8 being marginally faster, it seems to sell for the same price as the f/2. Of course Nippon Kogaku also made great lenses that would work too. For 85mm, I wholeheartedly recommend the Nikkor PC 8.5cm f/2 lens. I only have this lens in Nikon rangefinder mount and not LTM, but they made it for both mounts. A quick eBay search and prices seem to start at $269 and up from Japanese sellers.

I am also happy you’ve been enjoying the podcast, come on for the next show!

Many of us longtime Canon/Nikon shooters consider Canon’s 50/1.8 to be the sharpest 50/1.8 lens ever produced in Japan. That applies equally to LTM39, FL and FD versions. Franklin, you probably already know this, but if you shop Japanese sellers for old glass, inspect their listing photos carefully for internal haze and/or fungus. Japan’s climate is very humid, and many vintage lenses described as “EXC+++++” suffer those issues.