This is a Detrola 400, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by the Detrola Corp in Detroit, MI, USA between the years 1940 and 1941. The Detrola 400 was the most advanced camera produced by Detrola and would turn out to be its last before the company stopped producing cameras in 1941. Marketed as an American competitor to the Leica, the Detrola 400 had an aspirational feature set including an interchangeable lens mount, coupled rangefinder, cloth focal plane shutter with top 1/1500 shutter speed, and a body mounted electronic hot shoe. On paper, the Detrola 400 exceeded the specifications of the Leica III, but suffered from poor build quality, crude operation, and was produced by a company who could barely stay afloat. In total, only an estimated 800 of these cameras were ever built, making them one of the rarest American cameras ever made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 Wollensak Velostigmat Detrola uncoated 3-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: 38mm Thread Mount

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Coupled Rangefinder and Viewfinder Windows

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Detrola Hot Shoe (Not Compatible with Modern Hot Shoes)

Other Features: None

Weight: 678 grams, 540 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Detrola 400 is an uncommon 35mm rangefinder made by a company who had never made a 35mm camera before. Despite their lack of experience, the design and ergonomics of the camera is quite good, as is the Wollensak lens, which is capable of wonderful images. The Detrola 400 has a lot of things going for it, but one thing it doesn’t is reliability. Problems with the shutter and film transport plagued the camera, and as a result, very few were ever made. This is a rare camera that is extremely difficult to find, especially in working condition, but when it does work, is an easy to use a capable camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.2 | ||||||

History

In the 1930s and 40s. the name Detrola was most often associated with a successful line of radios manufactured by The Detrola Corporation in Detroit, Michigan. Founded in 1931 by John J. Ross, Detrola rose to fame for producing affordable radios during the Great Depression. Similar to another Michigan based radio manufacturer called the International Radio Corporation, Detrola employed the use of Bakelite in the construction of its radios.

In the 1930s and 40s. the name Detrola was most often associated with a successful line of radios manufactured by The Detrola Corporation in Detroit, Michigan. Founded in 1931 by John J. Ross, Detrola rose to fame for producing affordable radios during the Great Depression. Similar to another Michigan based radio manufacturer called the International Radio Corporation, Detrola employed the use of Bakelite in the construction of its radios.

First patented in 1909, Bakelite was a synthetic plastic like material which was durable, easily molded into a variety of shapes and colors, and for radios, had the benefit of not conducting electricity. By using Bakelite instead of wood or metal, Detrola could more easily build radios, but design them in a way that could mimic the color and texture of wood, which appealed to the design standards of the time.

Although Detrola sold a variety of different types of radios under their own name, a huge percentage of their manufacturing capacity was dedicated to making models which would be sold under other private brand names. They made Truetone radios for Western Auto, and Silvertone radios for Sears & Roebuck. It is estimated that Detrola radios were sold under as many as 100 different brands, some of which were for very small regional suppliers, so identifying a Detrola made model can be difficult for collectors today. Detrola’s advertising in the late 1930s proclaimed them to be the 6th largest maker of radios in the world, whether or not this is true is anyone’s guess.

Around 1938, Detrola would follow the lead of IRC, and jump into the camera industry by releasing their own line of Detrola cameras. IRC would later change its name to Argus and would have a very successful run in the camera industry, outlasting their radio business.

Detrola’s history as a maker of cameras was far shorter than Argus’, lasting less than 2 years. In the 2 years they made cameras, Detrola really only had two distinct models. The first was a series of Bakelite bodied scale focus camera which used 127 roll film, and the second was an ambitious 35mm rangefinder called the Detrola 400 which made its debut in the summer of 1940.

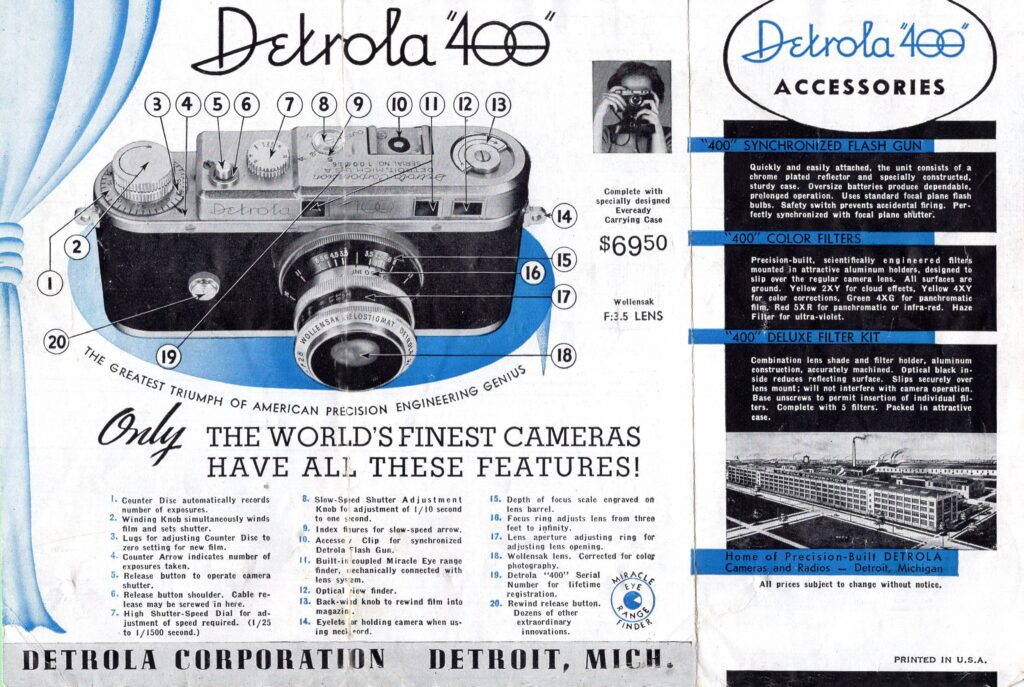

The Detrola 400 was heavily influenced by the German Leica rangefinder but was built to much cheaper specifications. It featured a stamped metal body with synthetic body covering, a removable back, folding rewind key, a top plate flash hot shoe, and a proprietary 38mm interchangeable lens mount, for which it is believed that only two lenses were ever made, a 50mm f/2.8 Wollensak Velostigmat triplet, and a 50mm f/3.5 Wollensak triplet. It had a flash hot shoe, a cloth focal plane shutter that could go as high as 1/1500 seconds, and a coupled “Miracle Eye” rangefinder with separate rangefinder and viewfinder windows.

The Detrola 400 was advertised with the 50mm f/3.5 Wollensak lens for $69.50 which was far cheaper than competing German rangefinders. When adjusted for inflation, $69.50 in the summer of 1940 is comparable to about $1650 today which put it well out of reach of those who were in the market for a $25 Argus camera.

The Detrola 400 is well known by most American camera collectors as one of the hardest to find for sale, but perhaps even harder is concrete information about its history, production, and available accessories.

In all the advertisements I’ve seen for the Detrola 400, all of them mention the f/3.5 Wollensak lens, but it is commonly stated that an f/2.8 lens was also available, yet an unscientific Google Image search only results in cameras with the f/3.5 Wollensak lens. Even the look back article, published in the March 1961 issue of Modern Photography only mentions the f/3.5 lens, possibly suggesting the f/2.8 lens was announced but never produced. If it was produced, it is certainly rarer than the f/3.5 that most seen to have.

Edit 11/28/2024: As often happens, shortly after publishing this review, dedicated collector Ira Cohen reached out to me to let me know that he does, in fact, own a Detrola 400 with the f/2.8 lens, putting to rest any doubt whether or not that lens was made. According to him, it is the only one he’s ever seen, and with lack of any promotional materials mentioning it, it is still safe to say that far fewer of the f/2.8 lenses were made than the f/3.5 lenses.

Another unseen accessory is the supposed “400” Synchronized Flash Gun which Detrola stated would use the camera’s top mounted hot shoe. In my research for this article, I could find no images of such a flash gun or evidence that one was ever made. Like other American cameras of the era like the Universal Mercury series and Candid Camera Perfex series which also feature top mounted hot shoes, these are proprietary designs which are incompatible with modern flashes today.

Finally, in what is perhaps the camera’s greatest mystery, the book “Glass Brass and Chrome”, by Karlton C. Lahue and Joseph A. Bailey, makes an egregious claim that as many as 250,000 Detrola 400s were produced, which seems impossible considering how expensive it was at the time, and the fact that so few of them have shown up in collections over the years. A production closer to 800 is much more probable and is the commonly accepted number today. If more than 800 were produced, a rumor exists that a huge number of cameras produced by Detrola were returned to the factory and dumped into Lake Erie. Whether this is true or not is unknown, but it is a fun urban legend to think about.

The Detrola 400, along with the company’s 127 roll film cameras all ended production in 1941 at the start of World War II at which point they started producing goods for the American war effort such as landmine detectors, aircraft radios, and other electrical components. Many sources online suggest Detrola had gone bankrupt in 1941, but evidence of the company’s radio output until at least the end of the decade suggests otherwise. Whatever caused Detrola to give up on producing cameras is unclear, but a failure to compete with other American and European camera makers seems most likely.

Detrola would eventually go out of business, probably around 1948, and although the company does not exist today, in 2017, Crosley Radio would resurrect the Detrola name with a new “4-in-1 Audio Center”, which plays records, CDs, cassettes, and has a built in AM/FM radio.

Today, the Detrola 400 is highly collectible for its reputation as a “Leica copy” (to which I do not agree), rarity, and historical significance. No one knows for sure exactly how many were made, but assuming the 800 number is close to accurate, these cameras are very difficult to find today. A quick search for Detrola 400s for sale on eBay as I wrote this article produced no results.

Whether you are a collector of 1940s cameras, Leica adjacent cameras, American cameras, or just like cool cameras, the Detrola 400 has something for everyone, unfortunately, very few people will ever see one.

My Thoughts

This review for the Detrola 400 might be a record for the longest time between when I first wanted to review a camera to when I actually got a chance to do it. I first learned of the Detrola 400 in the spring of 2016 when I was working on my review for the Detrola Model E which I had picked up the summer before. I had learned that this “American Leica” was a rare camera, but I figured if I put it in the back of my mind and passively kept an eye out for one, I would get a chance someday.

That chance came over eight years later in November 2024 when I had a chance to borrow one from the wonderful people at UsedPhotoPro in Indianapolis, Indiana. UsedPhotoPro is the online store for Roberts Camera and has been a source of many cameras and lenses I’ve picked up over the years. UsedPhotoPro had a listing for a very nice and fully functional Detrola 400 on their site for several weeks and it wasn’t getting any bids. Seeing that demand for a working Detrola 400 was probably less than they had hoped, I was put in touch with one of their directors, I asked if they’d be willing to loan the camera to me. The person I spoke to (I am intentionally not saying their name) turned out to be a fan of the site and was happy to send off the Detrola to me for a full review, in exchange for a mention in the article. So, as I am fulfilling my end of the deal, UsedPhotoPro is a great place to buy used photography gear, I was happy to get the chance to play with a camera I likely wouldn’t have otherwise had a chance to.

Having seen only a handful of Detrola 400s for sale over the years, all seemed to be in poor condition, showing oxidized bodies with peeling leather and non functioning shutters, but this particular example was in the best condition of any I’ve seen. When it arrived, I was immediatley impressed with how well this camera had been preserved. A tiny bit of oxidation was present around the edges of the top plate and there were some typical wear marks on the base plate, but overall, the camera was in stunning condition. The build quality was definitely a step above the typical American camera of the era, but clearly not up to the standards of a Leica. The stamped metal top and bottom plates show very few casting marks and have nicely beveled edges around the stepped portion of the top plate. The body covering was some kind of hard synthetic material which showed some minor wear marks but overall was still in tact with no cracks or missing pieces. Finally, the weight was right in that middle zone of “not too heavy, but not too light”, exactly as you’d expect a 35mm rangefinder from the 1940s to feel. While there are zero people on the planet who will mistake the Detrola 400 for a real Leica, that a low volume American manufacturer known more for making radios got as close as they did, is impressive.

Up top, we start with the rewind key. Looking similar to the types of keys you see on the bottom of a Zeiss-Ikon Contax, the Detrola’s design folds flush with the top plate when not in use, giving the camera a sleek look. Unfortunately, the key’s half circle handle is far too small to get a secure grip on while rewinding and ends up being slower than a traditional knob would have been. Still, it looks cool. Next is an engraving in a script font which says “Detrola Corporation”, and then below that “DETROIT, MICH, USA” and finally the camera’s serial number. Below the engravings is the Detrola’s flash hot shoe. Designed specifically to work with a flashgun which may or may not have ever been sold, the hot shoe is incompatible with modern electronic flashes, so do not try to mount one. Next to the shoe is the slow shutter speed dial with settings from 1 to 10, and an Out setting which must be set to use any of the fast speeds.

On a lowered step, is the main shutter speed dial with speeds from 25 to 1500 plus a Bulb setting. The inclusion of a 1/1500 shutter speed was very ambitious as real world speeds for the camera did not come anywhere close to being accurate. Only the very rare Univex Mercury CC-1500 claimed to have a 1/1500 shutter speed which gave both companies bragging rights as having the fastest 35mm camera shutter in the world. The shutter speed dial rotates both while advancing the film and firing the shutter. Changing shutter speeds can only be done with the shutter set as the chosen speed will not line up with the index mark otherwise. Special care must be taken to not let any part of your finger touch the shutter speed dial as the shutter is firing, as it will affect the motion of the curtains. Next to the shutter speed dial near the front edge of the camera is the shutter release button which has internal threads for some kind of proprietary cable release. A standard, internally threaded release cable cannot be used.

Finally, on the lowest step of the top plate is the combination film advance knob and exposure counter. The advance knob turns surprisingly easily on this example as I am able to rotate it by sliding the edge of my right index finger along the edge of the knob to give it a complete rotation in one single motion. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made, and must be manually reset after loading in each new roll of film.

The base of the camera has a 1/4″ tripod socket on one side of the camera, which means when mounted to a tripod the camera will not be perfectly balanced. In the center is the film door release switch, which has markings for Open and Closed. Near the edge of a little more than half of the bottom plate is an engraved “channel” whose purpose is not clear.

The edges of the camera are symmetrical with nothing to see other than metal strap lugs. The Detrola 400 has a removable back with no hinges, so there are no latches or anything else to see. That the lugs are there is a nice bonus as it means you do not have to depend on an ancient leather ever ready case.

Around back, the only thing to see are the dual eyepieces for the viewfinder and rangefinder windows. The layout of the windows is similar to that of the Leica IIb/IIIb cameras, except the rangefinder and viewfinder are flip flopped. Aside from that, there is nothing else to see on the back of the camera.

The film compartment is surprisingly nice for an American camera released in 1940. Unlike more economical cameras, no gears or inner parts of the shutter or film transport are visible as everything is nicely covered by the shutter box and other interior body pieces. Everything is painted black metal except for thick pieces above and below the film gate whcih are finished in chrome. I suspect chrome was used as it offers lower resistance as film transports over it. Film transports from left to right onto a non-removable metal take up spool.

The spool is single slotted and rotates clockwise, so that film winds on it opposite the direction it comes out of the case. Inside the film door is a polished chrome metal pressure plate. Like the chrome pieces above and below the film gate, I suspect chrome was used to reduce friction. Typically however, chrome pieces inside the film compartment was not a wise design decision as it encourages light to pass through the film, bounce off the pressure plate and double expose the film a second time from the other side. I doubt however, that enough people ever used a Detrola 400 to ever notice. Lastly, there are no light seals anywhere on the edges of the film compartment to protect it from light leaks.

Looking down upon top of the Wollensak Velostigmat lens, the arrangement of controls is pretty typical of 35mm lenses. Closest to the body is a black ring with an engraved depth of field scale. In front of it is the focus ring with engraved markings from just under 3 feet to infinity. Strangely, the focus ring on this lens stops just short of the actual infinity mark. I am uncertain if this is intentional, or suggesting that the lens is miscalibrated. I’ll have to wait until my first test images come out to know for sure. Closest to the front is the aperture control which has a black ring behind it showing f/stops from 22 to 3.5. On this example, the f/stop markings look like they were supposed to be paint filled, but the paint had worn away, making them difficult to read. Comparing this ring to those of Wollensak lenses on two different Perfex cameras I have, the arrangement of f/stops is backwards compared to those lenses, I am unsure why.

Up front, the Detrola 400 has a clean design with a script Detrola “400” logo engraved into the front of the top plate. Three windows for the viewfinder and rangefinder all have a raised bezel around them adding a touch of class, with one of the rangefinder windows having tinted green glass. Where you’d often find a self-timer lever on many 35mm cameras, instead is a round button which is used to deactivate the film transport for when you need to rewind film. Continuous pressure must be kept on this button all throughout rewinding.

The Detrola 400 uses a 38mm threaded screw mount. Like all screw mount cameras, removing the lens is a matter of securely gripping it and turning counterclockwise to remove, and clockwise to install. Strangely, the threads on the Detrola’s Wollensak lens are very long, meaning that you have to rotate the lens almost six and a half times to fully remove the lens. This is almost triple the amount of turns it takes to remove a lens from a LTM camera. Inside the lens mount is a rather long rangefinder coupling lever which gets in the way of mounting the lens, making it difficult to reattach. I found attaching the lens is easiest with it at minimum focus. Since there were no lenses of other focal lengths made for the Detrola, you would be wise to just leave the lens on your camera.

The Detrola 400 has separate windows for the viewfinder and rangefinder. For those unfamiliar with early 35mm rangefinder cameras, this was very common, and while later combined image rangefinders became favored over this style, it doesn’t mean that cameras with separate windows are inferior. Yes, it is slower to have to move your eye back and forth between two windows to focus and then compose your image, but an advantage is that by having the two windows separate, the rangefinder can have a different multiplication ratio than the viewfinder. This means that by magnifying just the rangefinder section, you can get more precise focus. This is especially useful when using telephoto lenses which require greater precision, but it is also beneficial for people like me with poor vision. Since the Detrola 400 never had a telephoto lens made for it, only the second benefit applies.

The rangefinder has a bluish tint to the main window and a green tint to the circular rangefinder patch which gives it nice contrast between the two images, making them easy to see. Considering the age of this camera, I was quite impressed with how well the rangefinder worked and how easy it was to use. To the left of the rangefinder window is the straight through optical viewfinder. Since there is no beamsplitter to take away some of the light, the main viewfinder on the Detrola is very bright and easy to use. The viewfinder has a magnification ratio less than 1x, which shrinks the image seen through the window. Although this means everything is smaller than life size, it does mean I was able to see all four edges of the viewfinder window while wearing prescription glasses.

The Detrola 400 is a pretty rare camera. If 800 of them were ever built, judging by how rarely they show up for sale, I believe that many of those 800 no longer exist, meaning that the true number that still exist in the world is much smaller than that. With such a rare camera, there is understandably little in the way of current information to read, so a lot of what I knew, or thought I knew about the camera came from the same few resources which suggested this camera was a poorly built camera made by a company who should have stuck with making radios.

After having a chance to handle the camera however, I realized that while this was never meant to be a direct competitor to German rangefinders of the time, to say that the Detrola 400 was a cheaply made and poor excuse for a camera, isn’t true either. My initial impression of the camera was positive, and I felt as though much of what little information that was out there, was wrong. With the excitement of shooting a camera that so few people have ever touched bubbling over, I couldn’t wait to load in some film and take it out shooting.

My Results

The Detrola was loaned to me with the assumption it was working. The guys at UsedPhotoPro advertised as it having been serviced, but it wasn’t clear by who. Whoever did it, upon receiving it, I put the camera through my usual round of testing, and everything appeared to be working correctly. The shutter curtains did not have any pinholes or other obvious light leaks and the shutter fired at all speeds, even the slow ones, at what sounded sorta accurate to the ear. Even the rangefinder moved as expected and seemed accurate at infinity, so I figured the only thing left to do was load in some film and shoot it! Never having imagined I’d have an opportunity to shoot a Detrola 400, for the first roll, I thought it would be cool to choose something that was available when it was new, so I picked Kodak Panatomic-X. The Pan-X from the 1980s which I was using was a different formulation than the stuff available in the 40s, but it was as close as I was going to get.

I quickly shot the hand rolled bulk Panatomic-X and developed it the same day I finished the roll. As I pulled the developed film from the Paterson tank, I was elated at what looked like a whole roll of properly exposed, in focus, and evenly spaced images. Shutter and film transport issues plagued the Detrola 400 even when it was brand new, so seeing a whole roll of what looked like perfectly normal 35mm images was very exciting for me.

My plan was to quickly shoot a second roll before I had to send it back, but realizing that I was holding a camera I was not likely to ever come across again, especially not in working condition, I knew I couldn’t send it back. I took a deep breath, put on my best “negotiating hat” and worked out a deal where I ended up buying the camera to keep. Yay! I now own a Detrola 400 and don’t need to rush through a second roll!

Having shot a number of cameras with Wollensak lenses, I expected to see good things from the Detrola’s Velostigmat lens and that is mostly what I saw. Images showed nice contrast and excellent sharpness in the center. A small amount of vignetting and a bit more softness crept in near the edges than I had expected, but neither were bad enough to ruin the images, in fact, I believe that these optical anomalies from the 1940 lens added some character to the images. I did not shoot any color film with the Detrola, but as I’ve seen with other uncoated prewar lenses, I imagine I’d see the same optical anomalies in the color images, but with muted color palettes and a tiny loss in contrast.

Overall though, I was very pleased with the images, they were as good or better than competing American and many German cameras of the day. Certainly they wouldn’t compare to a Zeiss Biotar or the best of what Leitz was making, but at a fraction of the cost, they didn’t have to.

More so than the image quality, the area I was most impressed with was the usability of the camera. I’ve shot many 1930s and 40s American rangefinder cameras by Argus, Clarus, Perfex and others, and while each of those models are capable in their own right, when I describe the shooting process with each, I usually describe them as “quirky” or say things like “in spite of” in my analysis of the shooting experience. For the Detrola 400, I was quite impressed with how well this camera works together. I won’t go as far as to describe it as “Leica-like” but it is clear that the shooting experience is similar enough to fully qualify for my “Leica adjacent” descriptor.

The Detrola 400 has good build quality and did not creak in my hands. The curved edges of the relatively thin body felt great in my hands and all of the camera’s controls fell exactly where my fingers expected them to be. The Detrola feels like a compact camera compared to the bulbous size of the Clarus MS-35 or the thick brick-like shape of the Argus C3.

Another thing Detrola got right was the viewfinder and rangefinder. Slightly larger than that of a screw mount Leica, I had no issue composing or focusing the images from my test roll, although there was a learning curve for me as the arrangement is opposite of how Leica and most other companies did it. If I had one complaint it was in the design of the folding handle on the rewind knob. While a fold out handle worked for other companies and also allows for an almost completely flat top plate, rewinding the film using the tiny handle was a challenge. The small size combined with that it can’t be raised away from the body meant that it continually slipped out of my fingers as I was rewinding the film. In this case, a normal knob that can be raised like in a majority of other 35mm cameras would have been a better choice.

Critics will point that the Detrola was a sales failure and that no more than 800 were ever made because they weren’t reliable and had problems with their shutter and film transport, and they’re not wrong. Clearly, this camera had issues which hampered its success, but at the very least, this review confirms that under optimal conditions, when everything is working correctly, the Detrola 400 was a good camera with a good design. I think combinations of poor timing right before the war and Detrola’s lack of experience meant that their first and only attempt was a failure. I do believe however, that with better luck, better timing, and perhaps a bit more goodwill from the American camera market, the Detrola was on the right track towards being a success.

As it is though, this is a rare camera that’s even rarer to find in working condition, and while I didn’t set out to buy a working Detrola 400, I am glad I did. This camera “completes” my collection of American 35mm rangefinder cameras with interchangeable lenses, and I am very happy to own it.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Detrola_400

Thanks for the great review, Mike! I saw this camera on UPP and was tempted by it, but of course didn’t buy it. I’m glad it ended up with you so the rest of us could experience it vicariously through your review.