This is an Ensign Selfix 820 Special, a medium format folding camera produced by Barnet Ensign Ross Ltd in London, England starting in 1953. The Selfix 620 Special was a higher end model in a long running line of Selfix folding cameras produced both before and after the war. When the first model in the 820 series was released in 1952, it was advertised as “probably the finest roll-film camera, designed successfully to beat all the German competition both in optical and mechanical performance.” The camera natively shoots 6cm x 9cm images on either 120 or 620 format roll film, or with a folding mask in the film compartment, twelve 6cm x 6cm images. It has an uncoupled rangefinder, which means you take a reading using the rangefinder only, and then manually transfer that reading to the front cell focusing lens. It has an eight speed Epsilon Synchro shutter, and came with a good 105mm f/3.8 Tessar-Style Ross, London Expres lens.

Film Type: 120 or 620 Roll Film (eight 6cm x 9cm or with mask, twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 105mm f/3.8 Ross, London Xpres coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Uncoupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Epsilon Synchro Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/250 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and F / X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 976 grams

Manual (similar model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/ensign_selfix_820.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Ensign Selfix 820 Special is an uncommon camera, especially in the United States that when it was released was one of the highest spec 6×9 British cameras. It has excellent build quality and features an uncoupled rangefinder which was a nice addition for it’s era, but is slow in use today. The 4-element Ross lens delivers sharp results that compare favorably to higher end American and German cameras of the day. This isn’t a camera most people will go out and seek, but if you were to come across one, it is a fine shooter. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.7 | ||||||

History

Ensign was the name of a London based company that made a variety of cameras and photographic supplies in the 1800s and first half of the 20th century. I’ll try to keep this short as there is a very thorough history of the Ensign company on Adrian Richmond’s Ensign Camera site. Ensign went through many name changes, acquisitions, and mergers over the years which causes their complete history to be a bit confusing. Rather than repeat everything here, I’ll try to come up with just a short summary, but if you’re interested to know more, I strongly recommend reading Adrian’s site.

Ensign was the name of a London based company that made a variety of cameras and photographic supplies in the 1800s and first half of the 20th century. I’ll try to keep this short as there is a very thorough history of the Ensign company on Adrian Richmond’s Ensign Camera site. Ensign went through many name changes, acquisitions, and mergers over the years which causes their complete history to be a bit confusing. Rather than repeat everything here, I’ll try to come up with just a short summary, but if you’re interested to know more, I strongly recommend reading Adrian’s site.

Ensign got it’s start in 1836 when two men, George Houghton, and a Frenchman named Antoine Claudet opened a glass warehouse in London. The company was called Claudet and Houghton and they specialized in all forms of sheet glass and that for optical products. The company continually increased their product offerings over the next 3 decades, eventually becoming one of the largest glass suppliers in all of England.

In 1867, George Houghton’s son joined the company and Antoine Claudet died, which resulted in a name change to George Houghton & Son. The new company would continue to expand it’s product offerings beyond glass, expanding into new markets, including photographic supplies. In 1903, George Houghton & Son introduced it’s first photographic film, which they branded as Ensign Daylight Loading Film.

In 1867, George Houghton’s son joined the company and Antoine Claudet died, which resulted in a name change to George Houghton & Son. The new company would continue to expand it’s product offerings beyond glass, expanding into new markets, including photographic supplies. In 1903, George Houghton & Son introduced it’s first photographic film, which they branded as Ensign Daylight Loading Film.

In 1904, Houghtons would acquire 4 different camera companies, Holmes Bros, A.C. Jackson, Spratt Bros., and Joseph Levi & Co., and would become a Limited company known as Houghtons Ltd. The patents and expertise of these 4 companies allowed Houghtons Ltd to become a major supplier of optical glass, film, and cameras in the early part of the 20th century, employing over 1000 people at all of their locations combined.

In 1915, Houghtons Ltd would acquire W. Butcher and Sons Ltd. and would be known as the Houghton-Butcher Manufacturing Company furthering expanding their product offerings and manufacturing prowess. In 1930, Houghton-Butcher would rename itself to match the name of it’s products, and would become Ensign Ltd. During this time, Ensign Ltd had a variety of cameras, from simple box cameras, folding cameras, and a miniature camera called the Ensign Multex.

In the 1930s, Ensign would release a new folding camera called the Selfix. The new camera was similar to many other folding cameras made by American and German companies of the era, but one feature that would become a staple of the Selfix series was that they included masks to support two, sometimes three different aspect ratios. Manny of the 6×6 models would support 4.5×6 images, and 6×9 models would support 4.5×6 images.

Most Selfix models were basic, offering a flip up or optical viewfinder and Ensign’s own lenses, but some “Autorange” models were created with uncoupled rangefinders, and a small number even came with Carl Zeiss lenses.

In 1939, Ensign would release a new box camera called the Ensign Ful-Vue. The Ful-Vue was a simple camera with a large brilliant viewfinder on top with a large viewing lens that was said to be bigger and brighter than any offered by any other company up until this point. The Ful-Vue was very popular with amateur photographers, and was often purchased for children due to it’s simplicity. It is one of the company’s most recognizable cameras today and one that most collectors think of when mentioning the brand Ensign.

During the war, Ensign’s company headquarters was destroyed by German bombers. In 1945, the company would merge with a company called Elliott & Sons Ltd who produced a film brand called Barnett. The new company would then be known as Barnett Ensign Ltd. Three years later, Barnet Ensign Ltd would merge with another British optics firm, Ross, and would become Barnet Ensign Ross Ltd. In 1954, the company’s name would be shortened to just Ross-Ensign Ltd.

During the war, Ensign’s company headquarters was destroyed by German bombers. In 1945, the company would merge with a company called Elliott & Sons Ltd who produced a film brand called Barnett. The new company would then be known as Barnett Ensign Ltd. Three years later, Barnet Ensign Ltd would merge with another British optics firm, Ross, and would become Barnet Ensign Ross Ltd. In 1954, the company’s name would be shortened to just Ross-Ensign Ltd.

After the war, Ensign would drop most of their prewar models, except the Ful-Vue and the Selfix. The Selfix models would be updated from their pre-war specifications and design, but would retain their signature “dual format” feature. The first new model to be released after the war was the Ensign Selfix 8-20.

To help with what was becoming a confusing lineup of model names, Ensign would begin a pattern in which the first digit of the model name would indicate the number of exposures the camera could make without a mask, and the second the type of film used. Since most Ensign models used what they called Ensign Type 20 film, which was identical to Kodak 120 film, most models ended with the number 20.

The Ensign Selfix 8-20 shot eight 6cm x 9cm exposures on 120 and 620 format roll film. Later models called the 12-20 and 16-20 shot twelve 6cm x 6cm and sixteen 4.5cm x 6cm exposures respectively.

Most models would also come in ‘Special’ and ‘Autorange’ trims, Special models had a redesigned top plate featuring an uncoupled rangefinder and usually had higher spec shutters and lenses. The Autorange models upgraded the rangefinder to a coupled version. Autorange Selfixes are extremely rare.

One final model in the Selfix series, called the Selfix Snapper was offered in 1953 as an entry level camera. It was a very basic model that came in a crinkle paint finished cast metal body. It featured a meniscus lens and single speed shutter, and was the only model in the Selfix series that did not support dual aspect ratios.

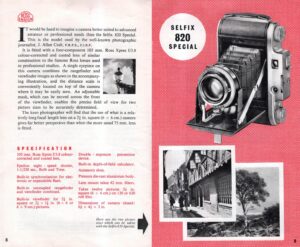

The Ensign Selfix 8-20 Special being reviewed here was likely one of the company’s better selling models as it was consistently mentioned in catalogs and ads for Ensign cameras that I found while researching this article. I found no evidence of production numbers, but most likely they weren’t rare. In the ad to the right from Wallace Heaton, the 820 Special model sold in 1955 for £28 9 9 and the Autorange model for nearly twice as much for £50 7 0. I found no evidence that these cameras were exported to the United States, and converting historical British Pounds to current US Dollars is extremely difficult.

I was unable to determine exactly when the Selfix 8-20 Special ended production, or for the entire Selfix series for that matter, but Ross-Ensign Ltd. would continue producing cameras until 1961 at which point all camera production would stop. Immediately after the war, countries like England, France, and the United States saw an uptick in demand for homegrown cameras as models from Germany were very difficult, and in some cases, illegal to source. This allowed companies like Ensign to thrive, producing their own products for prices far less than German imports would, but as relations with Germany improved by the mid to late 1950s, imports of high quality German cameras became easier and less expensive.

In addition, the rise of the Japanese camera industry brought in a large number of well built and inexpensive models to photographers all over the world, giving stiff competition to smaller companies like Ross-Ensign. By the 1960s, a huge number of these smaller photographic firms would find it no longer economical to keep producing their own products, so many exited the camera making business.

Today, Ensign cameras like the Selfix are fondly remembered by those in the United Kingdom who remember the brand during it’s hey day. Many of these cameras were still sold as new old stock or gently used models in the decades to come, and many still can be found today in thrift shops or at boot sales. Outside of England however, Ensign models are hard to find, especially in the United States. Online marketplaces like eBay and Etsy make them a bit more easy to find, but without many highly desirable models or brand recognition, few are sought after by Western collectors. Still, if you find one of these in good condition, they’re worthy of being added to your collection.

My Thoughts

In the short time since the Camerosity Podcast was created, I’ve unintentionally created an entirely new channel of potential readers of this site who on occasion will have a camera that they offer to loan me for the purposes of a review. While I am constantly humbled by the level of trust these people give me, a complete stranger with their cameras, on the plus side, a loan almost always follows up with a continuing friendship with someone I keep talking to.

In the case of the Ensign Selfix 820 Special, that person was Miles Libak, a frequent caller on the podcast who can be often seen sipping on a Cosmopolitan or some type of craft wine!

In early 2022, Miles reached out and asked if I wanted to play with his beautiful Ensign. This camera had recently received a full CLA from Jurgen Kreckel at cert6.com and was fully functional. Of course I said, in my finest fake British accent, and on it’s way from over the pond Minnesota it came! When the box arrived from Miles, I remarked at how heavy it was and wondered what other bonus items he included in the box. Maybe there was a surprise second camera or some accessories that added to the package’s weight because after all, one folding camera couldn’t possibly be this heavy!

Upon opening the box and seeing that there was, in fact, just a single camera in there, I couldn’t believe how heavy it was. At 976 grams, the Ensign Selfix 820 Special is 163 grams heavier than the not-insignificant Royer Teleroy and 121 grams heavier than the “also British” Kinax III which I have yet to review. The Ensign is certainly an impressive camera both in looks, size, and weight!

The top plate is unusually cluttered for a 6×9 folding camera as a good portion of it houses the uncoupled rangefinder. From left to right, we start with a pretty standard film advance knob, which is engraved with a clockwise arrow, and the words “Made in England”. Next to it is the top plate shutter release which has a rudimentary double exposure prevention feature. Upon pressing the shutter release, the button will become unlocked, preventing you from pressing it again until after advancing the film. I should point out however, that the double exposure prevention lock is defeated only slightly after beginning to advance the film. This means you can fire the shutter well before reaching the correct spot on the film for the next exposure, overlapping it with the previous feature. Even with the double exposure prevention, it is important to pay attention to the exposure numbers through the red windows on the back of the camera.

In the middle is the uncoupled rangefinder. A large serrated wheel sticks forward from out of the top plate with engraved distances from just under 5 feet to infinity. To operate the rangefinder, you look through the eyepiece and look for the coincident image rangefinder patch. Unlike with coupled rangefinders, focusing the lens and the rangefinder must be done in two separate steps. Using the serrated wheel, you line up the coincident images, and then take a reading of the distance on the wheel. Then, you must transfer that reading to the lens by rotating it. Taking a reading on the rangefinder without then changing the focus on the lens will produce out of focus images.

One final knob on the far right of the top plate is the uncoupled depth of field scale. The knob itself does not actually turn, and only lifts up, which is used when loading film into the film compartment to pull the spool shaft out of the way. The uncoupled depth of field scale works similarly to the uncoupled rangefinder in that you need to take a reading on the scale separately from anything that is happening to the lens.

On the side of the camera opposite from the top, there is a 1/4″ tripod socket and two small feet, that when combined with a hinged kickstand on the side of the shutter mount, will support the camera when sitting on a flat surface. A second 1/4″ tripod socket exists on the outside of the folding door for mounting the camera to a tripod in portrait orientation.

Around back, you see the round eyepiece for the viewfinder and rangefinder window. On the door are two metal sliders for covering the red exposure number windows, one for eight 6cm x 9cm images, and when using the baffle, twelve 6cm x 6cm images.

Opening the left hinged (with the camera laying on it’s side and the rangefinder facing up) film compartment reveals a pretty standard 6×9 roll film compartment. Film transports from right to left onto removable spools. As is the case with all roll film cameras, the previous supply spool should be moved over to become the take up spool before loading in a new roll of film. The Ensign, like many British cameras of this era, supports both 120 and 620 format roll films. A stepped key on the winding knob allows both types of spools to be inserted without any issue.

On the inside of the film door is a large metal pressure plate with the necessary holes for the two red exposure number windows, plus a decorative decal reminding you to ask for Ensign size 20 film, which was the same as 120 film made by any other film maker.

With the camera in portrait orientation, looking down upon the camera, first we see a leather carrying strap above the sliding door lock for opening the film compartment. Above the shutter is a slider for controlling the lens diaphragm, with f/stops from f/22 to f/3.8 listed. Near the marks for f/11 and f/8 are two flash sync ports for F and X sync. A red mark to the right of f/16 indicates a recommended setting for focus free snap shots in good lighting. Above the shutter is the cocking lever, which is not coupled to the film transport and must be activated before making every exposure. Finally, off to the side is the socket for a cable release.

The viewfinder is of average size for a 1950s folding camera. It is not as gloriously large as a ones found on the Voigtländer Vitomatic IIa, nor is it as squinty as on an early Kodak Retina. I found that with prescription glasses, I had no trouble seeing the entire rectangular image without having to press my face against the camera.

The main part of the viewfinder is tinted yellow and the circular rangefinder patch is clear. This helps with contrast, making seeing the double image very easy. I prefer the method of tinting the entire viewfinder, as opposed to just the rangefinder patch like on most cameras with coincident image rangefinders. I never had a chance to test it as the camera did not come with the 6×6 mask, but by sliding a little lever on the front face of the camera, a mask blocks off the sides of the rectangular viewfinder, showing a square image. In the gallery above, I show the viewfinder both with the 6×6 mask on and off. In both images, the circular rangefinder patch is difficult to see, but this is a symptom of how I captured it with my smartphone. In person, the rangefinder patch is much easier to see.

Edit 3/7/2023: Within a mere hours of posting this review, eagle eyed reader Martin pointed out that the camera has a built in 6×6 mask via two folding flaps in the film compartment. Wondering how I could have possibly missed such an obvious feature, I took a look at the camera, and sure enough, Martin was right!

The Ensign definitely does have two flaps in the film compartment that can be folded shut to shoot square images. Of course this change must be done before loading film in the camera, so it can’t be switched mid roll, but what a nice feature unlike other cameras who used removable masks which can be lost over time. Thanks Martin!

Overall, the Ensign Selfix 820 Special has the look and feel of a high quality camera. The rangefinder is uncoupled which will likely turn off someone not used to having to separately measure their distance and set it on the lens. This certainly slows you down, but is hardly the deal breaker it might seem, as for most landscape or mid range outdoor shots, you can rely on the lens’s depth of field to get properly focused images. I wouldn’t ever try to use the rangefinder unless I was doing closeups, and for that, the additional help would be useful.

The Ensign Selfix 820 Special is a special camera indeed. It has a good build quality, what looks to be a capable lens, and a good number of features, but what is it like to shoot? Keep reading…

My Results

My first roll through the Ensign was in the summer of 2022, and for that, I chose a roll of slightly expired Kodak Portra 160NC which I assumed would give me pretty decent shots as I’ve shot the same film of the same age before. Sadly, due to a total brain fart while developing that roll, I completely ruined it by mixing up my chemicals, rendering the entire roll useless.

It would take a few months into late fall of that year before I would take the Ensign out again, this time with expired Fuji Neopan 400. This time, I was careful to handle and develop the film properly and ended up with a proper roll of eight exposures.

When Miles offered up his Ensign for review, he had said it was previously CLAd and worked perfectly, so I had high hopes for the images I would get from it. Certainly helping matters was that the shutter seemed snappy, the blades and glass were clean and the rangefinder appeared to work.

As expected, the images from the Ensign appeared nicely in focus and properly exposed. The 105mm f/3.8 Ross London Xpres lens rendered nice and sharp images with only the slightest hint of softness near the corners. I found the black and white images showed good contrast and although I didn’t shoot a second roll of color in this camera, there was nothing to suggest the colors wouldn’t have been properly represented as well.

Edit 3/18/2023: In an earlier version of this review, I had listed the Ross Xpres as a triplet, but was corrected by multiple people that it is a 4-element Tessar style, and that very early Ross Expres lenses were actually a 5-element design, but this one is almost certainly a 4-element one.

It is difficult for any lens to produce razor sharp images corner to corner on a 6×9 camera, but the ones produced by the Ensign were about as good as you’d expect from a 1950s medium format folder. If I had one negative thing to say about the images is that they were a tad sterile. For a lens made by a respected, but uncommon maker like Ross, I had hoped I’d see a bit more character, but these images look like those from most decent folding cameras I’ve shot. Of course, that’s not a bad thing, just something to consider if you are the kind of person who likes to see ‘character’ in their images.

Using the Ensign Selfix was a pleasure. Although I am no stranger to uncoupled rangefinders, I found that I didn’t need it for my test roll as I never shot any closeups. Had I done a second roll, that is something I would have likely explored. Uncoupled rangefinders can be just as accurate as coupled ones, but they’re slower to use, and require extra steps that people unfamiliar with them, might not enjoy.

The Selfix is very solid and gives good confidence in it’s operation while holding it. I very much liked the yellow tinted viewfinder with clear rangefinder patch as it made seeing contrast between the two very easy. In terms of build quality and feel, the camera compares favorably to other higher end 6×9 folders in my collection such as the Royer Teleroy and Kodak Monitor Six-20. I was never able to find out what these cameras cost new, but they were clearly on the higher end of what would have been available at the time and I suspect original owners were happy with their purpose of such a premium camera.

Minor nitpicks were the left handed operation of the top plate shutter release and location of the right sided eyepiece, which is opposite of what my preferences are. I’ve never been fond of folding cameras like the Selfix, Kodak Bantam Special, or Welta Weltini II where the door is on the left. It just feels more natural for me to have it on the right, but it’s hardly a deal breaker. Although heavy, the weight wasn’t a major issue for me, however I suppose that if you were going on a long photo shoot with this, and planned on shooting many rolls all in a row, it’s heft might eventually get to you.

Overall, the Ensign Selfix 820 Special is a heck of a camera that when found in good operational condition would be an excellent addition to any collection, whether you specifically like British cameras, 6×9 folders, or just a cool camera. They’re not very common, especially in the United States, so it’s not likely I’ll ever add one to my permanent collection, but I am thankful to Miles Libak for lending me this one!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Ensign_Selfix_8-20

http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/entry_C599.html

https://www.photo.net/forums/topic/505721-exercise-equipment-the-selfix-820/

Jurgen Kreckel recently did masterful CLAs on two Franka folders. In response to a subsequent request for another camera overhaul, he advised me that he’s spending less time at the bench and more time out shooting film. Maybe this here old fart should follow his lead ….

Hi Mike, great review as always. I have the non rangefinder example in my collection, haven’t shoot it yet though. Just one note – 6×6 mask is built in as fold out flaps in the film compartment

You have got to be kidding me! How did I miss this?! I just checked the Ensign and sure enough, there were the two flaps for making square images. I have updated the review with a picture showing the masks closed, and have given you credit for pointing this out to me. Thanks Martin!

Happy to help Mike! And one more update, the lens is (or at least should be) 5-elements in 3-groups modified Tessar design with cemented rear triplet. As some sources say it’s either four or five element Tessar, I have checked the chunky rear group with a flashlight and it shows four reflections (triplet). Maybe the 1-1-3 lens design is why images “lack character”.

Nicely reviewed, the Ross Xpres lens is a 4 element Tessar lens, however.

Thanks David, I have corrected the review…

Thank you for trhowing light on this little known camera. I purchased one some years ago after hunting quite a while for an affordable 6×9 folder with a rangefinder and a four element lens. Yes, I belive it has four elements and is a Tessar type. My research at the time found that early Ross Xpres lenses were five element to get around the Tessar patent, but that they changed the formula when the patent expired. Right now I have a freshly loaded film in the camera so there will be no flaslight inspection for a while. Four or five elements – the lens is very sharp and free of “character”, which is much to my liking. I bought this camera with the purpose of making big, grain free negatives for black and white winter landskapes while skiing in the Norwegian mountains (yes, I live in Norway, but not in the mountains). I can confirm it’s heavy. It hasn’t seen nearly as much use as it deserves. I’m also a little disappointed by the rangefinder as I haven’t found it too accurate on close range. I consider anything closer than ten feet to be close-up in the 6×9 format. Perhaps it needs a service. It should not be too difficult, I think. I don’t think this camera was ever sold new in Norway. I bought mine via e-bay from Great Brittain.

Thanks for the additional information Andreas! You’re not the only person to correct me on the lens design. I swear I did research before I posted it and couldnt find anything! These are wonderful cameras and had this not been a loaner, I likely would have shot it multiple times.

As for rangefinder accuracy, I think that uncoupled ones are difficult to keep aligned, as the slightest bumps can throw them off, as opposed to coupled ones that are physically connected to the lens. I feel like that has to have some effect of keeping them aligned. I could be wrong though. Still a cool camera!

Although I have four folders already, they are all Zeiss. So I’m now going to look for

a British made camera. Sounds like this is the one to have.

It is a great camera. Another really terrific folding Ensign is called the Ensign Commando. It is a 6×6 rangefinder, similar to the Super Ikonta 6×6.

Mike: I’ve now purchased one from specialty camera dealer Peter Loy in London. As I only intend to make 6 X 9 contact prints with Ilford FP4, can you tell me which of the two red windows do I utilise? There’s a central one and one nearer to the leather strap end. I’ve used 6 X 6 before in a Rolleiflex and a Hasselblad for E6 slides but like 6 X 9 for prints. Perhaps Martin could help? My camera arrives Tuesday.

It’s a bit late but the numbers in the center of 120 film are for 6×6. For 6×9 you need to use the red window along the edge of the film.

The early Xpres lenses were originally a 5 element modified Tessar, probably done to avoid the tessar patent. Once the Tessar patent expired they went to 4 elements I believe.