This is a Stereo Bob XV, a stereoscopic folding camera made by H. Ernemann Werke AG in Dresden, Germany starting in 1913. The Stereo Bob XV was part of Ernemann’s long running Bob family of cameras that were produced from about 1902 until the company’s merger with Zeiss-Ikon in 1926. The Stereo Bob XV has a wood and aluminum body, covered in genuine leather, giving it a sturdy and high quality feel. The camera shoots 4.5cm x 10.7cm stereo pairs (each individual image is about 5cm wide) on an early form of 1 5/8″ wide roll film most closely resembling 121 roll film. This film has the overall length of 120 but the width of 127, meaning that if you can cut down a roll of 120 to 127 width, and you have two 121 spools, you can shoot film in it.

Film Type: 121 Roll Film (eight 4.5cm x 10.7cm stereo pairs)

Lens: 65mm f/6.8 Ernemann Deketiv Aplanat uncoated 4-elements in 2-groups

Focus: 3 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Flip Up Glass Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Stereo Ernemann Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/100 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 554 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Ernemann Stereo Bob XV is an uncommon folding stereo camera that used 121 format roll film. It’s build quality is comparatively high for other German cameras of it’s era and with a range of shutter speeds, f/stops, and full focus capability would have been a flexible camera in it’s day. Very few of these cameras were ever made, suggesting they didn’t sell well, making them very hard to find today. If one should ever cross your path, they are well built, easy to use, and are capable of good results, but most likely will only ever been seen displayed on a shelf. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 50% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.5 | ||||||

History

The early days of the German camera industry saw a dizzying number of camera and optical companies that produced cameras, lenses, scopes, and other photographic accessories. Over the first couple decades of the 20th century, many of these companies acquired, or were acquired by other companies, sometimes continuing their earlier products under a new name, but other times, vanishing into oblivion.

One of these companies was Heinrich Ernemann, Aktiengesellschaft für Cameraproduktion in Dresden. Formed in 1899 by Heinrich Ernemann, the company took over production of the Globus view camera from Herbst & Firl of Görlitz, Germany and produced that camera until 1919.

In it’s early days, Ernemann produced a large number of photographic accessories, but by the start of the 20th century, produced several different types of cameras and movie projectors.

Heinrich Ernemann was a savvy businessman, sending his son Alexander to work in the United States to build up his experience in international relations.

With his and his son’s experience, Ernemann was able to survive an onslaught of other Dresden area camera makers, when in 1909 four of his biggest competitors, Richard Hüttig AG in Dresden, Kamerawerk Dr. Krügener in Frankfurt, M Wünsche AG in Reick near Dresden, and Carl Zeiss Palmos AG in Jena were forced to merge into a single company, Ica.

Around this time, Ernemann produced a wide number of different types of cameras, from simple box cameras, folding cameras, stereo cameras, and reflex cameras. In In 1910, an Ernemann employee named Johan Steenbergen helped to design many of the company’s early reflex and folding cameras, eventually leaving in 1912 to form his own company, Ihagee Kamerawerk GmbH.

One of the most successful lines of Ernemann cameras was the Bob series of folding cameras. A large number of Ernemann Bobs were produced from about 1902 until 1926 when the company would eventually merge to become part of Zeiss-Ikon. Bob cameras came in a huge number of shapes and sizes. Most used roll film, but there were some plate film versions too. Using sizes anywhere from 4cm x 6.5cm all the way up to 8.5cm x 14cm, there was a Bob camera for every budget.

Around 1909, a stereo camera called the Bob V Stereo was introduced that came in a compact folding body, shooting stereo 4.5cm x 5cm images on what I assume was 121 format roll film. Most sources online suggest the camera shot 4.5cm x 10.7cm images, but this is the total width of the film gate, combining the two images together. The actual exposed images are nearly square, approximately 5cm wide.

The Stereo Bob V would eventually be replaced by a similar model called the Stereo Bob XV in 1913. Looking at images of the Stereo Bob V and the Stereo Bob XV in this review, the most notable differences are a lack of apertures to choose from, less shutter speeds, and a centrally located viewfinder. Although I cannot make out which lens the Stereo Bob V in the left has, I would guess it is some lesser lens.

In my research for this article, I found very little about the Stereo Bob XV other than a couple images of one sold at auction. Comparing the specs on my example and the limited information I could find for the Stereo Bob V, it is pretty clear the Stereo Bob XV was just an upgraded Stereo Bob V.

I also could not find any advertisements or prices for either camera. My best guess is these were only sold in Germany or at least exported to German speaking areas of Europe as there is no evidence they were sold in the United States or other English speaking countries. Neither the Stereo Bob V or Stereo Bob XV appear in either an undated Ernemann catalog from around 1908 or a 1924 catalog in Pacific Rim’s reference library.

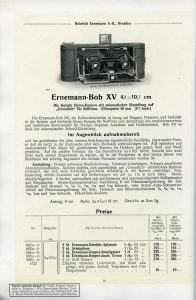

Edit 2/16/2022: After posting this review, an astute reader of this site named Keith Brooker found the following page from a 1914 Ernemann catalog for the Stereo Bob XV. An earlier catalog from 1912 does not show this model, confirming the start date somewhere in the middle, likely 1913.

What I find the most interesting in this catalog is the four different lens options and two different shutters available for it. My version of the camera was the lowest spec version with the f/6.8 Detektiv Aplanat and 1/100 shutter, which cost 110 Marks. The top of the line model had an f/6.3 Zeiss Tessar and a shutter with a top speed of 1/300 and cost 280 Marks.

The Stereo Bob XV probably wasn’t produced for very long, which is why info about them is hard to find and they rarely ever show up for sale. The Bob series would continue on as it had with a number of different models over the next decade or so.

The outcome of World War I decimated the German economy and throughout the 1920s, a great number of German optics companies struggled. Those who didn’t have established relationships with western distributors found it hard to sell products domestically in a weak and over saturated economy.

As a result of an increasingly failing industry, in 1926 at the suggestion of the German government, the Carl Zeiss Foundation would take control over four of Germany’s leading optics companies, Ica, Ernemann, Contessa-Nettel, and Goerz, and form Zeiss-Ikon.

A condition of the merger, the German government insisted that none of the plants from the original four companies be closed, nor any employees laid off. Zeiss-Ikon had the dubious task of finding a way to integrate dozens of similar photographic products and lenses, along with lesser known products like automotive lamps, key lock systems, and light bulbs, into a single cohesive catalog.

After the merger, Zeiss-Ikon would slowly start to whittle down the number of models they produced, eventually closing the door on many Ernemann produced models, but the company’s biggest legacy wasn’t any of it’s cameras, rather the Ernemann Tower, which was the first high-rise building in all of Germany and considered to represent the pinnacle of the Dresden area camera industry. The Ernemann factory continued to be used by both pre and post war versions of Zeiss-Ikon and would eventually become immortalized in the logo for VEB Pentacon.

Today, there’s not likely many people who would specifically look for the Ernemann Bob XV Stereo, but it represents a period of high quality and innovative German cameras that are very collectible. This is an uncommon camera made by a once great company that if it hadn’t been for two world wars which weakened, and later collapsed the German camera industry, might still be around today.

My Thoughts

One day, my wife had told me that a friend of hers had an old camera that belonged to some distant relative and wanted me to take a look at. I asked what kind of information her friend had about it, but all he could tell her was that it was very old and it was folded shut. Assuming that the camera was likely one of a zillion early 20th century Kodak folders, I said that I would be happy to help, but that her friend shouldn’t have very high expectations as most early folders are worth very little.

When the camera arrived and I could see that not only was the camera not a Kodak, but that it was an uncommon German folding stereo camera, I became much more excited!

The Ernemann Stereo Bob XV is not only the first Ernemann I’ve handled, but it is also the first folding stereo camera I’ve had. Like most pre-war German cameras, the Ernemann has a very good build quality. The outer body is aluminum wrapped in a high quality leather covering. I am unsure of what kind of leather this is, but whatever it is, it has held up remarkably well, showing very little signs of aging, and has even managed to retain it’s suppleness, giving it a luxurious feel in your hands.

The inner body is made of black painted wood. Upon removing the back of the camera, an inner chassis including the parts above and below both film chambers and the film gate shows a high quality grain which I have no way of identifying. Although mostly painted black, the paint has worn off in a few areas showing a deep brown color to the wood.

Opening the Stereo Bob XV requires sliding a round metal button on the camera’s top plate in the direction of the folding viewfinder. Doing so will release the latch holding the camera shut, but gravity alone isn’t enough to fully open it, as you’ll need to help it the rest of the way.

Once the camera is fully open, you’ll see both lenses and shutters. When looking down from the top of the camera, the shutter on the right is the primary one which controls the shutter speeds from 1-100 plus T and B, and has the shutter release. The shutter release is a self-cocking design, so the process of cocking and firing the shutter is done with one single motion. The shutter on the left has the control for aperture from f/6.8 to f/22. Both the shutter speed and aperture controls work for both lenses via a linkage that goes between the two lenses.

A small reflex viewfinder rests between the two lenses on the front edge of the door. Like most reflex viewfinders, the image is reversed left to right when looking through it at waist level. It is common for mirrored surfaces like this on older cameras to lose their reflective coating, but this one was still in good enough condition to still be usable. A second folding viewfinder also exists on the top plate for eye level shots giving the Stereo Bob XV two options for composing your images.

The camera’s back has little else other than a red window for viewing exposure numbers on the film’s paper backing, and the rear of the flip up viewfinder. The original type 121 roll film would have had exposure numbers for up to eight stereo pairs. Since I have never seen a roll of original 121 film, I am unsure if it would have numbers 1 through 8, or if it would require you to skip numbers for other non-stereo 121 film cameras. If I ever find out, I’ll come back here and update this.

The film compartment is opened by sliding a metal latch on the camera’s left side. The film door is not hinged and will come off after releasing, so take care to not let it fall and hit the floor. Also notice how deep the camera is front to back, compared to it’s rather shallow height.

With the back off, we see the film compartment with two film gates, one per lens. The take up side is on the left and has a metal winding key above it. The supply side is on the left.

The inner body of the camera is made of wood, and in the image to the left, you can see a bit of the black paint has worn off below each gate revealing the wood’s original color. A piece of black velvet is between the two gates to maintain film flatness and prevent scratching as film travels through the camera. The film pressure plate is a single, long piece of metal that spans both gates.

The example I had for this review did not have any original 121 spools, but some previous owner was clever and cut down plastic 120 spools to the correct height of 121 and then glued them back together. 121 film is rather easy to recreate as the spools have the exact same length and diameter as 120, but the height of 127. If you have access to a slitter that cuts 120 down to 127 size, you can easily make your own film for this camera, just by using two shortened 120 spools.

A Note About 120 Film When using cut down 120 film in the Ernemann Stereo Bob XV, the 120 exposure numbers will not line up with the red window on the back of the camera. In order to advance the film correctly, after attaching the film to the take up spool and closing the back, 15 half turns of the key is enough to get the film ready for the first exposure, and then 2.5 half winds for exposures 2 and 3, and then 2 half winds for the rest of the roll. This should be good enough to not overlap any images.

Both the take up and supply spools are held in by hinged metal spool holders which are removed by pulling on a piece of black leather which is wrapped around to the back of the spool holder. Simply tug on the leather and both the spool and it’s holder should come out together. When removing the take up spool, you must remember to first lift up on the winding key to allow clearance for the holder to come out. With the spool holder out of the camera, the top and bottom of the holder flip out of the way allowing you to easily remove the spool. Loading the camera is very simple as you take the holder, align the spool, fold it shut, and then slide both pieces back into the camera together. When inserting the take up spool, there is a top and bottom, so you must pay attention to which side you are putting in.

With film loaded in the camera, it is time to make some stereo images. Using the Ernemann Stereo Bob XV is similar to most folding cameras of the era. Exposure is controlled via two sliders, one on each lens, and focus is done via a chrome lever on the camera’s front right side. A focus scale is on the front left side, next to the “H. Ernemann AG Dresden” logo.

Focus distances are measured from 6 meters to infinity. The scale does go closer than 6 feet, but without markings, it is not clear what the true minimum focus is for this camera.

Despite having two viewfinders, I ended up guesstimating my exposures. I didn’t quite understand how the folding viewfinder worked as the back part is a spring loaded post that doesn’t stay in the up position by itself, and I found the reflex finder to be too small to be effective when composing. As I likely wasn’t ever to use any of these exposures in a stereo viewer, I just pointed the camera in the general direction of what I wanted to photograph and hoped for the best.

The Stereo XV Bob is a high quality and well thought out stereo camera that would have likely been used as a portable version of much larger stereo cameras, by those who traveled a lot.

It is clear that whoever has owned this camera in the 100+ years since it was made, took care of it. It likely wasn’t used much, but despite it being in such nice shape, I didn’t have very high hopes for it. With this being the first ever stereo roll film camera I’ve used and the first that uses 121 film, I needed to figure out a way to load film into it.

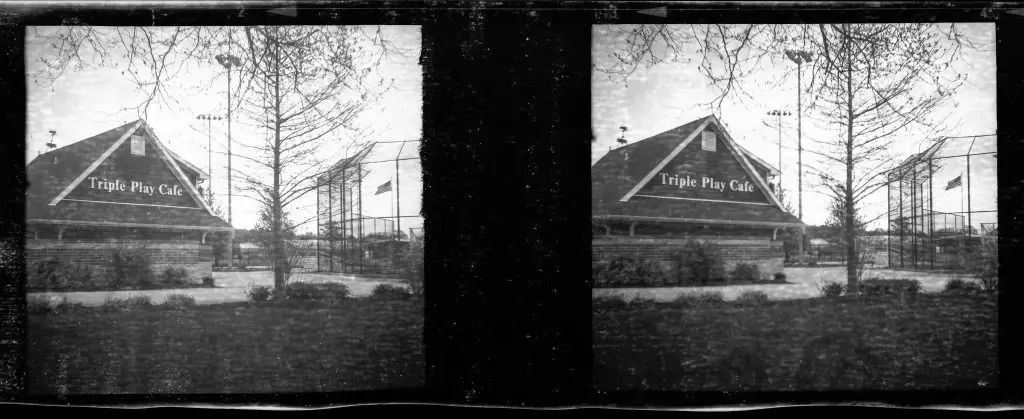

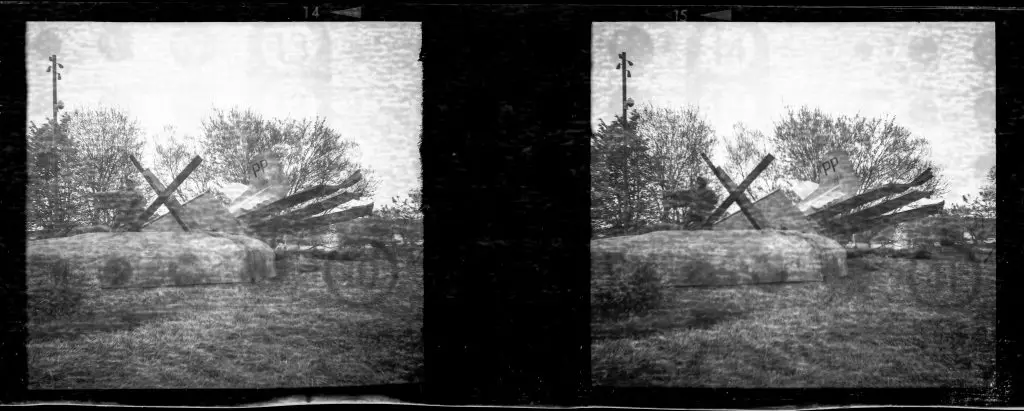

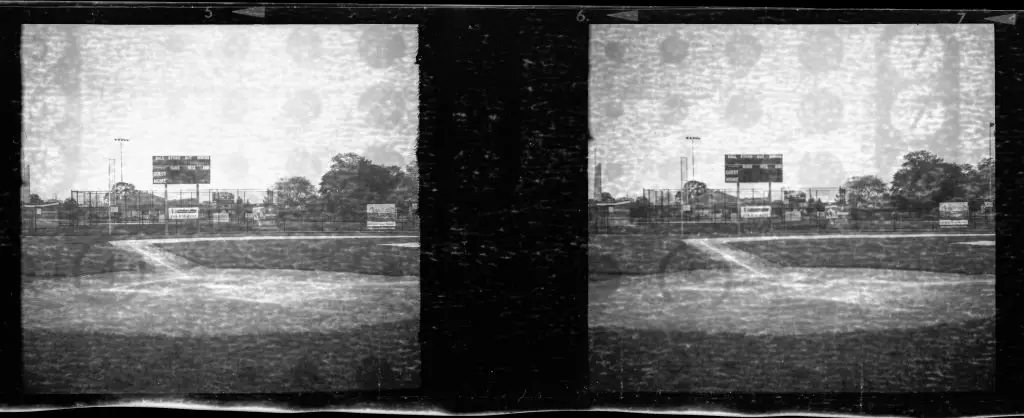

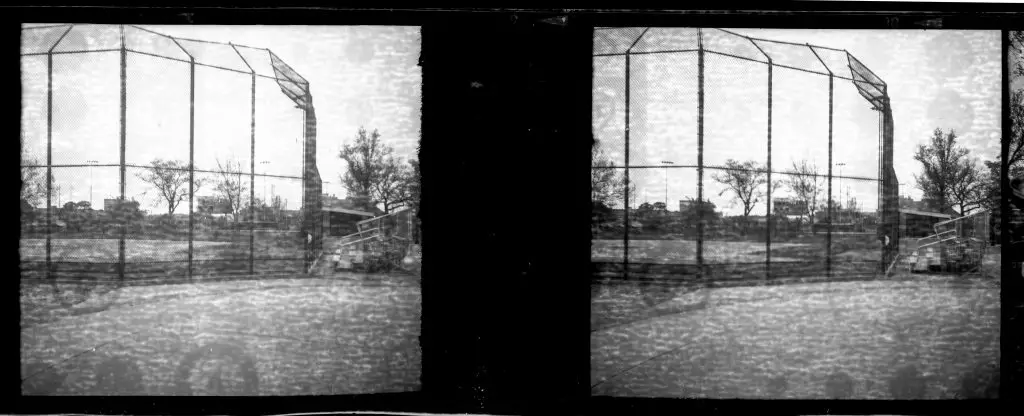

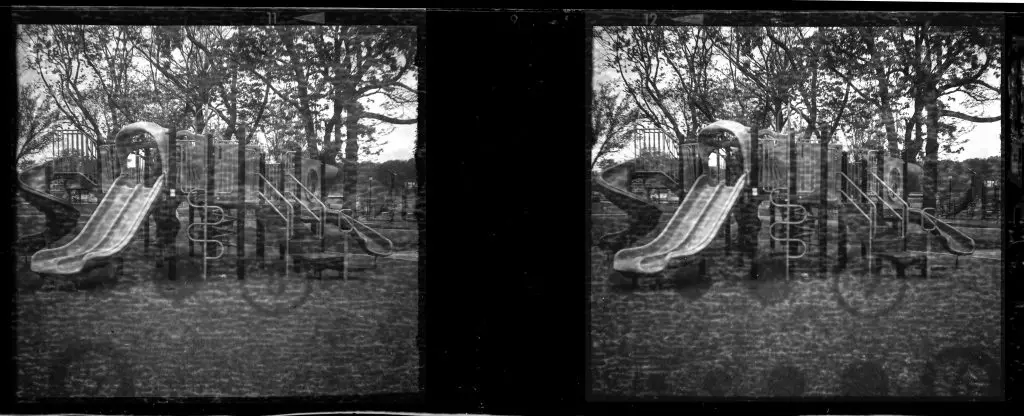

My Results

When I first picked up the Ernemann Stereo Bob XV, it had a very weak shutter that got stuck more times than it didn’t. With several liberal dousings of naphtha, I was able to free it up enough to where it fired. It seemed like the shutter blades on one side worked with more force than the other, making me question whether both images would expose an image equally.

Not wanting to risk an expensive film, I opened my bag of heavily expired Ilford 50 film. While most slower speed black and white films age well, this film doesn’t. I’ve shot it in other cameras as a test film and knew it would likely show ink transfer from the backing paper along with other signs of degradation. Still, I figured it’s slow 50 speed would be a good match for whatever the shutter could do.

It would take me a bit of time to figure out how I wanted to load film in it, but with it having the exact same width as 127 film, I used a 127 slitter that cuts down regular 120 film and loaded it onto the makeshift spools that came with the camera. The film fit perfectly, so the only thing left to do was take it out!

As I had expected, the film was in very poor shape with degradation across the entire span of the film plus ink transfer from the backing paper. Despite the conditional issues of the film, the exposures were quite good, still showing a decent amount of detail. One of the shutters is definitely slower than the other, showing a bit more exposure on one side than the other, but the results were still useable.

Zoomed in on my 27″ computer monitor, there’s a fair amount of sharpness in the center with some noticeable softness near the corners, but nothing you wouldn’t expect from a simple early 20th century lens. Vignetting is also visible, but again, nothing that I didn’t expect. I don’t know much about Deketiv Aplanat lenses but the word “aplanat” suggests this is a 4-element in 2-group design, similar to the Dallmeyer Rapid Rectilinear which is also regarded as a good lens for center sharpness with good control over aberrations near the edges.

With two viewfinders, a range of six shutter speeds plus B and T, a good range of aperture settings, plus the ability to focus from 6 meters to infinity, the Stereo Bob XV was a pretty flexible camera.

This is a nice camera, but I find it’s biggest weakness is it’s rather simple lens and shutter combination. As an economic stereo camera, what’s included here is probably good enough, but considering most cameras of this era had a wide availability of lens and shutter combinations, I wonder if others existed with higher spec lenses and shutters.

I went back and forth about wanting to shoot a second roll of film in this camera, perhaps even color, but in the end I decided not to as I don’t know that doing so would have taught me anything new about the camera. Despite being a stereo camera, using the Ernemann Stereo Bob XV is very similar to most folding cameras of the time.

One thing that I am curious about, is that with this camera’s uncommon film size, how many people would have actually used it? Compared to other roll film types of the early 20th century, 121 wasn’t used on many cameras. I would guess that most users of this camera would have their images contact printed onto cards and placed into some kind of hand held stereo viewer. I don’t think anyone would have made slide transparencies with this camera, not just because that kind of film wasn’t common then, but also that custom slide holders would have needed to be made for 121 film.

This camera likely had a very short production run, maybe only for a year or two. There is little to no information about this camera online, nor does it appear in any of the Ernemann or retail catalogs for stores selling Ernemann cameras of the era.

Although I think this is a cool camera, it’s not one you’ll find easily today. In my research for this article, I could only ever find the existence of one other, suggesting that few will ever show up for sale. If you do find one however, know that this was a well built camera that likely delivered good results to whoever would have bought it new. If you want to shoot it today, be prepared to jump through hoops cutting down film, developing, and scanning the film, but most likely any others will just end up sitting there on a shelf for display only.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Ernemann_Bob#Bob_V_stereo

https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/scienza-tecnologia/schede/ST110-00436/

A rare camera indeed. Any idea why the name “Bob” was chosen for so many Ernemann cameras?