If your idea of enjoyable photography is picking up a camera, turning it on, pointing it at something, pressing the shutter release, and getting great images 100% of the time, then collecting and shooting old film cameras is not for you.

One of the many reasons you hear for why people still like to shoot film these days is that they enjoy the process. Film slows you down and it changes your approach to photography. When you only have 36, 24, 12, 8, or even a single exposure loaded in your camera, you’re going to be more discriminate about what you choose to photograph, than someone with a digital camera with a memory card capable of holding thousands of shots.

Not everyone agrees on the benefits of being slowed down however, as sometimes those same things that slow you down become a point of contention among film camera collectors and users. I like to call these complaints “Film Photography First World Problems” in that in the grand scheme of things in the world today, are pretty minor, yet they seem to come up often as deal breakers or reasons to not shoot film.

Here is my list of five film photography first world problems, all things that are commonly mentioned pain points for some people. Each of these examples are things I’ve encountered myself, and maybe get annoyed at a little too, but perhaps aren’t as big of a deal as some people make them out to be.

Bottom Loading Leicas / Trimming the Film Leader

Perhaps the single most complained about film photography first world problem is with bottom loading 35mm cameras. The most notorious of these are screw mount Leicas and their countless copies, but even later M-series Leicas, and those made by other companies like Wirgin used a bottom loading design too.

You would think that a critical element of using one of the most popular cameras of the 20th century wouldn’t be so contentious, but for many, it is. People who are not fond of bottom loaders are quick to champion hinged or removable back cameras like the Zorki 4, Tanack 35, and Canon P.

The challenge with most bottom loading cameras is two-fold, physically loading the camera, but also having to trim the film leader. For anyone who has yet to experience this, the film leader on a bottom loading camera needs to be about 10cm long, or roughly double that of the length most 35mm film comes in these days. Years ago, Kodak and some other companies used to sell film with a Leica length leader, but as these cameras fell out of widespread use, the leader was shortened.

On occasion, you’ll run into someone who says they have successfully loaded a bottom loading camera without trimming the leader, but it is very hard to do, and often results in jammed film and in some cases can damage the fragile shutter curtains within the camera.

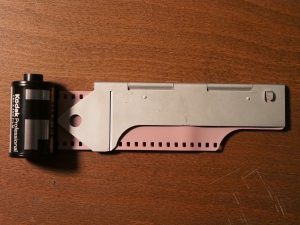

Years ago, companies like Ernst Leitz produced a device called the ABLON which was simply a hinged piece of metal that folded over the end of a new roll of 35mm giving you a template for trimming the proper length of film. The ABLON is a desirable piece of Leica memorabilia that is sought after by collectors, even if they never use them. With prices sometimes exceeding a couple hundred dollars on eBay, some recent attempts to make modern equivalents such as the Photonbox film trimmer, or even some DIY 3D printed solutions have become more affordable options.

For anyone new to shooting film cameras, it is easy to think that acquiring and using one of these trimmers is a necessary requirement for shooting a bottom loader, when in reality a simple pair of scissors is all you need. The exact length of film doesn’t have to be precisely 10.00000cm on the nose, you simply have to trim enough of the film that it reaches from one spool to the other.

In terms of loading a bottom loading camera, yes it is a little slower than a camera in which you load from the back, and the first couple of times you do it, you will likely fumble around, but I promise that if you practice with a junk roll of film for maybe 5 minutes, you’ll get the hang of it and after that, loading a bottom loading camera takes barely any longer than a camera with a removable back. It’s hardly the deal breaker that I think some people make it out to be.

Respooling Kodak 620 Film

In the early 20th century there were as many as 30 different competing roll film formats, all coming in different sizes and shapes offering different numbers of exposures for what was then an overwhelming number of cameras being produced by companies in Germany, the United States, and elsewhere.

At that time, the Eastman Kodak Company was one of the world’s largest producers of film. In 1932, in an effort to standardize film offerings, created two new film formats they would exclusively offer in many of their forthcoming roll film cameras. These two new formats were called 616 and 620 and used an identical film stock from existing 116 and 120 film formats, but on a smaller spool that would allow for camera makers to make smaller cameras.

Ever since these formats were created, Kodak received criticism for creating what was essentially a “Kodak-centric” format that was incompatible with the huge number of 116 and 120 cameras out there. Although the new cameras were smaller, there was really no other benefit other than for Kodak to make more money having their own unique format. While Kodak would release a huge number of cameras using 620 film, only a few other companies would follow suit, mostly on lower end basic cameras.

Kodak would stop producing new cameras that used 620 film in the 1960s and would discontinue the format altogether in 1995, making using these cameras by collectors today a challenge. While there isn’t a huge demand for Kodak’s basic Jiffy and large number of 620 Brownies, there were a few models like the Kodak Medalist and Chevron that are worthwhile today, yet people often complain about those models needing 620 film which you can’t get anymore.

The difference in 620 vs 120 is only the spool and not the film, which means if you have a 620 spool, you can simply roll 120 film onto a 620 spool and you end up with 620 film. You can buy pre-spooled 620 film through stores like the Film Photography Project, or you simply do it yourself as long as you have a couple of empty 620 spools. This next video by Michael Raso from the Film Photography Project shows how it’s done.

I see comments all the time in camera collector groups saying things like “if only XXX camera didn’t use 620”, and frankly, it’s but a minor challenge. There are many video tutorials online showing how it’s done, and with a small amount of practice, rolling 120 film onto 620 is something you can do in less than 2 minutes in a film changing bag or a room with the lights off.

For me, this additional step that I can do while I sit on my couch and watch TV, is minor compared to the payoff of shooting a camera like the Kodak Medalist, which I believe is one of the best cameras of the 20th century. If the Medalist is outside of your budget, you owe it to yourself to try the Argoflex (Argus) Forty too!

Nikon Lenses Rotate Opposite Everyone Else

The above two Film Photography First World Problems are both things that I don’t think are as big of a deal as some people make them out to be, but at least I can kinda see how some people might be turned off by bottom loading and 620 cameras if they don’t have the time. This next one puzzles me, however.

Yes, there are people who hate that Nikon F-mount lenses rotate opposite of pretty much every other SLR camera lens. Now, I’m sure there’s probably some off the wall camera that I’m not thinking of that works like the Nikon, but as I am writing this, I have in front of me a Minolta SRT-101, Canon AE-1, Mamiya Auto XTL, Yashica Electro AX, and a Zeiss-Ikon Icarex 35, and on all of them when looking at the front of the lens, minimum focus is when you rotate counterclockwise. To focus to infinity, you rotate the lens clockwise.

With all Nikon F-mount cameras, it’s the opposite, infinity is counterclockwise, and minimum focus is clockwise.

This “backwards action” also applies to the aperture ring and bayonet mount as with the Nikon, f/stops are indicated from smallest to wide open and a clockwise twist of the lens is needed to remove it, and everyone else, it’s counter clockwise.

Why did Nippon Kogaku do this? I’m not sure anyone knows the answer for sure, but looking at my Nikon S and S2 rangefinders, I noticed that they rotate like the Nikon F does, in which infinity is counterclockwise and minimum focus is clockwise. Since the Nikon rangefinder is based of the Contax rangefinder, and the original Contax was designed by Dr. Heinz Küppenbender, and who knows why he did it, so if my completely baseless theory is correct, you can blame the backwards rotating Nikon lenses on Küppenbender.

Now that we know the reason for the backwards Nikon lenses (not really), the next question is why does anyone care? What’s the big deal? Honestly, I can’t answer that either. In all my life using Nikon SLRs, I’ve never once thought, “Wow, this is annoying that infinity is the opposite direction as every other SLR.” In fact, the first time I had ever heard someone complain about this, I had to pull one out and look for myself. I guess from an aesthetic standpoint, when looking down upon the lens at the focus scale, it kinda makes sense to have the focus distances go from left to right from smallest to largest, but I’m also not in the habit of looking at focus distances on most SLR lenses.

Film Cameras Can’t Shoot Digitally

Wait, what?! How is this a problem? Of course a film camera can’t shoot a digital picture….why would anyone even want to try?

Well, therein lies my fourth First World Problem, because there are enough people out there who want to turn their film cameras into digital ones that various Kickstarter / GoFundMe projects keep getting proposed, and in some cases, getting close to reality to where people can actually buy them.

Perhaps the most notorious film to digital conversion is the “I’m Back”, a product developed by a Swiss company of the same name who makes digital backs that fit a majority of 35mm cameras and another which can be used on some medium format cameras.

If this sounds exciting to you, then perhaps you’d like to read more about it, but ever since “I’m Back” was first announced in 2017, every single article or YouTube video about the product is more of a promotional commercial that glowingly covers it’s features, without any real world use, and none of it’s cons. Google it for yourself and as of August 5th, 2020 as I write this, everything you’ll find from PetaPixel, NikonRumors, DIYPhotography, DPReview, and other sources cite the same basic facts and “best case scenario” testimonials.

I would love to read a real hands-on review of the I’m Back from an independent source who owns one and can give a fair assessment of it’s strengths and weaknesses. The manufacturer already states that the images from the I’m Back aren’t meant to compare to digital or even real analog pics with this statement:

I’m Back was created with the intention of reusing the old analog in a digital way, but maintaining a “retro” aspect in the photos thanks to the focusing screen. It is not intended to have the quality of a digital camera of last generation, therefore, it is not an accessory to be at par with a digital or even an analog.

Looking at how it works, you can understand why the images aren’t as good as the digital sensor is located in a tube near the bottom of the device, and it photographs an image of a focusing screen placed in the film gate of the camera, through a series of macro lenses. The light path entering the 35mm camera’s lens, is reflected onto a ground glass, which then is reflected 90 degrees by a mirror through an unknown number of macro lenses, and then captured by a digital sensor.

Taking a picture requires putting the camera in Bulb mode, leaving the shutter open for as long as it takes for the electronics to capture an image through the open shutter. If one of the appeals of using an old camera is in the mechanical sounds the shutter makes, you’ll lose that with this device as the camera is merely a vessel to pass light through. In a simple sense, imagine taking the back off your film SLR, sticking a piece of frosted ground glass in the film plane, and then mounting a digital camera behind it, and taking digital pictures of the focused image while the shutter is held open in Bulb mode.

If you’re still interested and think this is something you might want to play with just for fun, the prices on it are rather prohibitive. A quick look at current prices on Indiegogo, the kit with just the universal back, digital module, and all necessary cables to make it work costs $351, with each dedicated back costing an additional $50, and since it ships from overseas, add on an additional $23 in shipping to the US.

Now, I’m not here to shit on the efforts of this company or it’s product as clearly a lot of time and effort went into creating this product, but every time I read about the I’m Back, I can’t for the life of me understand who would want such a product that ruins the beauty and ergonomics of many old cameras, only works on those with removable backs, has an image quality less than both digital or an analog photo would through the same camera, and costs nearly $400, just to “play with”.

Film Cameras are Too Expensive

There’s the old joke that if parents want to keep their kids off smack, they should introduce them to photography as then they won’t be able to afford drugs, and it’s funny because like most hobbies, photography is a rabbit hole that can get very expensive very quickly.

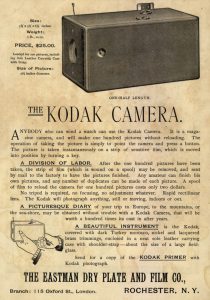

When the George Eastman Company released the first Kodak camera in 1888, it was a simple box camera that took 100 circular photos on a single roll of film that couldn’t be removed or developed by the user. Doing so requiring sending the camera back to Eastman and paying $10 to get the film developed and have a new roll installed. When adjusted for inflation these prices compare to $681 and $272 today. Imagine paying the equivalent of $272 every time you wanted to reload your camera!

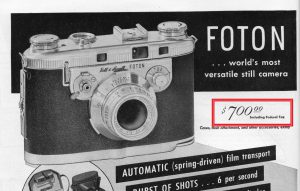

In terms of cost, things both got better and worse in the years that would follow. In 1938, you could spend $3.50 on a Univex AF-5 or $213 for a Leica III with 50/2 Summar which compare to $64 and $3915 today. Perhaps my favorite example is the Bell & Howell Foton’s $700 price when it first went on sale in 1948, which when adjusted for inflation is an eye-popping $7433 today! Now THAT’S expensive!

At the turn of the 21st century, film cameras started to be replaced with more and more digital cameras. By 2010, nearly all professional and amateur photographers had ditched their 35mm and other format film cameras for shiny new digital models, and sold off their prized possessions for very little. It was not unusual in those days to pick up screw mount Leicas and Nikon F3s for under $100 which was a far cry from what those cameras would fetch on the used market a decade earlier.

About half a decade later, a funny thing happened and film cameras started to regain some popularity. No longer were cameras sold for pennies on the dollar, now they were sold for nickels and dimes on the dollar. Instead of paying $20 for that nice Canon AE-1, you now had to pay $50. A Rolleiflex could no longer be picked up for $75, now you had to pay $200 or more.

Normally in any industry, when prices jump 200% or more, people rightfully freak out, but for film cameras, a bit of perspective was needed to see the big picture. The reason Leica M3s are now fetching four figures on the used market is because that’s closer to what they should sell for.

For fun, I loaded up Google Books and randomly picked the November 1994 issue of Popular Photography and browsed through the dealer ads. On page 94 is an ad for Cambridge Camera Exchange in New York City which had a large section of used equipment. Here are some highlights.

For fun, I loaded up Google Books and randomly picked the November 1994 issue of Popular Photography and browsed through the dealer ads. On page 94 is an ad for Cambridge Camera Exchange in New York City which had a large section of used equipment. Here are some highlights.

I picked a total of eight cameras from their price list, then looked up the Consumer Price Index’s 2020 Inflation Adjusted price, and then did a search on eBay for sold auctions for the same camera.

For the eBay auctions, I looked for examples that were body only, and at least made some claim of working, eliminating broken or parts cameras. Since Cambridge would have only sold working cameras, and likely would have offered some sort of 30 day money back guarantee, I didn’t want to include the cheapest possible broken eBay cameras.

I looked at several different retailers offering used equipment and could not find any with a price for a Leica M3, but I found it interesting that the older IIIF had an inflation adjusted price that was in line with what they cost today.

Hilariously, the Yashica T4 which gets my vote for “most overpriced camera of 2020” is nearly TRIPLE that of it’s 1994 price with inflation. People are really paying $440 for these cameras (sometimes even higher).

You’ll notice other user cameras like the Nikon F3, Contax RTS, and Minolta Maxxum 7000 are selling today for anywhere from 5 to 14 times less than their inflation adjusted prices. If I had more time, it would be interesting to see how the used camera prices fluctuated from year to year, and at what point prices started to plummet. If I had to guess, in 2004, ten years after this ad, I would be willing to bet a Nikon F3 was not selling for anywhere the $699 price listed here (even without inflation).

Where I’m going with this is, that even with an uptick of prices today from five years ago, we’re still getting amazing deals on MOST stuff. Save for the outliers like the T4, Contax G2, and Olympus Mju-II.

Get Out and Shoot

So there you have it, my take on five complaints I’ve heard more than a few times from collectors new and old about shooting film in 2020. As I said at the beginning of this article, if a completely sterile, effortless, and trouble free experience is what you expect out of photography, then film probably isn’t a good fit for you, but if you’re reading this article, you’re likely not that person.

So there you have it, my take on five complaints I’ve heard more than a few times from collectors new and old about shooting film in 2020. As I said at the beginning of this article, if a completely sterile, effortless, and trouble free experience is what you expect out of photography, then film probably isn’t a good fit for you, but if you’re reading this article, you’re likely not that person.

If however, you’re new to this hobby or are just curious about film and have heard any of these five film photography first world problems, then take it from me, it’s not a big deal. Load up that Leica IIIf, Yashica TLR, or Pentax K1000 and have some fun! I know that’s what I do!

Well done! I was smiling and nodding (in affirmation) the whole read!

Good points made Mike.

On the reverse aperture ring of the Nikons; you might find it interesting that on my two Kilfitt Killar macro lenses, the f3.5 E has f22 on the right (looking down on it from the shooting position) and the f2.8 D version has it on the left!

Brilliant. I really would like a digital back at some point…as a choice. My issue is that my C41 chemicals go off so quickly. I need to solve that problem.

Peggy, you’ve mentioned your struggle with C41 chems going bad in the past, and I’d really like to know more about how you store them. I have gotten at least 6 months and 30+ rolls from every single C41 kit I’ve ever bought.

I’ll be the voice of dissent. I shoot digital and film. Digital because the images are superior in quality. Film because of nostalgia.

Shooting film has had no effect whatsoever in the manner in which I capture images. Perhaps I have better discipline than most.

And sometimes, just like with digital, I blow through three rolls (or fill a memory card) in a single afternoon because I’m having.

I think some film photographers like film because it requires more effort and it’s harder for the novice to get good results. Anyone can pickup a digital camera and quickly learn to get good results.

I think it’s important to qualify the expression “shooting film”, because it’s not the same to do it with a 6×6 folder from the ‘40s than with an automatic SLR from the ‘90s. When I shoot with the latter, I do it just as if I were shooting digital, since those cameras are pretty reliable and easy to use. But with the former, just because of how clunky such a camera can be, it forces me to slow down.

I think that their choice of equipment weighs heavily on which side of this debate people fall into.

An intriguing read, thank you for your insights here. By the way I did also own an earlier Takumar lens that rotated in reverse.

Mike, some folks just are natural-born complainers! You might add Item #6 to your list of First World problems: The non-AI f5.6 twist. Having worked pro with Nikon F gear for a few years, that little boogie woogie to index the Photomic head to the lens’s max aperture is still second nature – just as is balancing the removable back on my knees while changing film.

How funny. Americans suffer from a lot of 1st world problems (oh how they suffer), but the modern digital button-pusher seems especially prone.

Two comments:

Many films before the mid-1960s came with the longer tongue. They were ready to use in thread mount Leicas.

Leica’s R8 and R9 had a digital back that could be attached. Unfortunately, it was bulky and very expensive. Do any of these backs still work?

Mike, Nicely done. I’d like to read more posts like this, which seems to feed upon your experience of collecting and research. You’ve touched upon peeves that are just the tip of the iceberg. Whole articles probably could be written on just viewfinders or shutter releases alone…