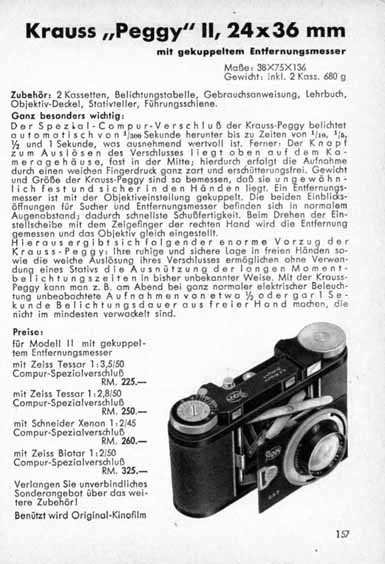

This is a Peggy II, a 35mm rangefinder camera produced by Gustav Adolf Krauss in Stuttgart, Germany starting in 1932. Two versions of the Peggy were made, the Peggy II upgrades the base model with a coupled rangefinder. The Peggy has a collapsible lens and shutter mounted to a metal plate and suspended by twin struts and uses leather bellows to keep light out of the film compartment when the camera is open. Although not featuring a non-removable lens, it could be purchased with a variety of lenses, this version here with the top of the line Schneider Xenon 4.5cm f/2 lens. The Peggy II is an attractive camera with a black enamel body and nickel accents. A chromed silver version of the camera was also made. The Peggy was likely created as a less expensive alternative to the Leica Model A which was popular at the time.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 4.5cm f/2 Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon uncoated 6-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Viewfinder and Coupled Coincident Image Rangefinder

Shutter: Compur Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: Film Slicer

Weight: 615 grams

Manual: https://www.flickr.com/photos/camerawiki/albums/72157712454308601

How these ratings work |

The G.A. Krauss Peggy II would have competed with the Leica Model D, but looked and functioned completely differently. This version, with an excellent Schneider Xenon f/2 lens produces excellent results which rival the best of what other German camera companies had to offer. What it lacks in interchangeable lenses and optional accessories, the Peggy more than makes up for in performance and charm. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.6 | ||||||

History

The history of the company or the man G.A.Krauss, who build the Peggy II is very sparse. Google searches for the name “Gustav Adolf Kruass” returns either the same two paragraphs of information easily found on camera-wiki, or information about a man with the exact same name who studied soil and forest biology in Dresden. I am fairly confident that the camera Krauss and the soil scientist Krauss are not the same person as the years which they were active do not line up.

What little is known about the Gustav Adolf Krauss who made cameras is that he had a brother named Eugen Krauss who worked with him as early as 1895 in a camera distributor in Stuttgart.

Shortly after starting their business together, Eugen Krauss would emigrate to Paris where he would start his own camera shop called E. Krauss & Cie as a distributor of German optical products and eventually making lenses, binoculars, and eventually cameras.

Gustav would remain in Stuttgart operating his shop and eventually getting into production of lenses and cameras like his brother. Many of Krauss’s early cameras like the Krauss Rolette were produced under license from Zeiss.

Like the cameras made by Eugen Krauss, the Gemran Krauss company’s camera output consisted largely of simple folding roll film cameras. Clearly, however, Gustav had aspirations for something greater as in 1931 at the Liepzig Spring Fair, would debut an all new 35mm camera called the Krauss Peggy. Although I could find no evidence of this, the creation of this camera almost certainly was in response to the rising popularity of the Leitz Leica camera which by the time the Peggy likely would have went into production was already gaining in popularity.

Upon it’s release, the first Peggy received positive reviews in the press with some calling it a masterpiece. The first version lacked a rangefinder and only had an optical tube, similar to the Leica Models A, B, and C. It had a collapsible lens and shutter on a folding strut and bellows design. Focus was controlled via a knob on the top plate of the camera rather than on the lens itself. The lens on the first version was a Zeiss Tessar 50mm f/3.5 but later versions were produced with a f/2.8 Tessar. Prices for the camera with both lenses was RM 178 and RM 218 which was considerably cheaper than the Leica.

Unlike the Leica, the Peggy offered two unique features. The first was a cassette to cassette film transport system in which the film never needed to be rewound. Instead a film cutter inside the film compartment could be used to slice the film near the edge of the film gate, allowing the user to unload film mid roll, not requiring you to finish the roll before developing exposed images. This feature predates a very similar feature used by Ihagee on the Kine Exakta from 1936 and may have even been the inspiration for it. The second feature was an automatic shutter cocking feature in which the shutter is automatically cocked by extending the lens. To recock the shutter after an exposure, you’d collapse the front plate and then erect it again.

A year after the Peggy’s release, a rangefinder equipped version called the Peggy II would make it’s debut. The rangefinder on the new model was a coupled coincident image type in a separate window with about a 1.5x magnification, like the Leica. Unlike the Leica though, the rangefinder eyepiece was on the opposite side of the camera, requiring the photographer to move his or her eye a lot farther than with a Leica (or Zeiss-Ikon Contax which debuted the same year).

When it first debuted, the Peggy II retained the automatic shutter cocking mechanism from the original model, but this would later change, instead opting for a more traditional cocking lever on the Compur shutter. At the same time of the release of the revised Peggy II, the original model was re-released as the Peggy Norm, and it too, also lost the automatic cocking feature possibly suggesting reliability problems or that users didn’t like having to keep closing and re-opening their camera each time they wanted to make another exposure. Based on my un-scientific method of Google Image Search, it would seem that versions with the automatic cocking system are more common as fewer are found with the manual lever, like the one reviewed in this article.

The Peggy II, being a higher end model added additional lens options to the f/3.5 and f/2.8 Zeiss Tessars offered on the original model. For only RM 10 more than the 2.8 Tessar, the camera could be ordered with a Schnieder-Kreuznach 45mm f/2, or for RM 65 more than that, the top of the line Zeiss Biotar 50mm f/2 lens. Additional evidence from a UK catalog for A.O. Roth suggests that an f/2.7 Meyer-Makro Plasmat and f/3.5 Meyer Primotar Anastigmat were also available. As best as I can tell, only the non-Rapid Compur shutter was available for the camera. Versions of the Peggy with a chrome plated instead of black enamel body also exist.

In my research for this article, I found no evidence that the Peggys were ever sold in the United States as other than the A.O. Roth catalog mentioned above, all advertisements for the camera are in German, nor does it get mentioned in any of the US catalogs or publications that I have access to.

For photographers of the era who wanted a premium and well featured German 35mm rangefinder, but couldn’t afford a Leica or Contax and had no need for interchangeable lenses, the Peggy II likely was an incredible option, but it would seem the camera was short lived. According to Kurt Tauber at kameramuseum.de, all Peggy models ended production in 1934 with a total of between 10,000 and 15,000 built.

It is not clear why production of the camera ended, but there is evidence to suggest that G.A. Krauss’s photographic store in Stuttgart continued to operate as his grandson, Rolf Krauss would take over the business in the 1950s and continue to operate it into the early 21st century.

Krauss may have been a short lived camera maker with a very short list of innovative or high quality cameras, but that’s what makes cameras like the Peggy extra special. Not only are they good looking and unique examples of pre-war German innovation, but that they came from a company that few have ever heard of, make them highly desirable by collectors.

Assuming that the numbers are correct of ten to fifteen thousand cameras made, the Peggy is uncommon, but not rare, as a quick eBay search for “Krauss Peggy” on the Worldwide version of eBay, produces 5 for sale. The prices aren’t cheap, however the fact that any given moment, at least a couple are for sale suggests that if you really want one, you can get one.

Today, collectors like uncommon cameras, they like German cameras, they like prewar cameras, and they like good cameras. The G.A. Krauss Peggy II checks off all those boxes meaning that this is a camera any serious collector should definitely have in their collection. If you’re not a collector, and prefer to use your cameras, it’s a well built and high quality camera, that if found in good shape should be capable of really nice images.

My Thoughts

The Peggy has a curious place in camera history. When you think about to early 1930s 35mm cameras, one of two models usually comes to mind, either the Leitz Leica or the Zeiss-Ikon Contax. The Leica came first, going on sale in 1925 without a rangefinder or interchangeable lenses, but an iconic shape, control layout, and cloth focal plane shutter. The Contax came later, in 1932 as a competitor to the Leica. Meant to surpass the Leica in every way, from quality, features, to lens selection, both cameras were extraordinarily expensive and far beyond the budget of a mere casual photographer.

What if you were in the market for a German made 35mm camera that came with good lenses, had a reliable shutter, and a coupled rangefinder, but you didn’t have a huge budget? Was there a third option?

Shortly after the release of the Contax, models like the Kodak Retina II, Certo Dollina II, and a few others would fill that niche, but before them was the Peggy, an elegant looking camera with a black enamel on brass body, with a collapsible bellows, leaf shutter, coupled rangefinder, and good lenses.

When picking up the Peggy II, one thought that will not come to mind is “economy”. The Peggy may have been an economically priced model, but it feels every bit as high quality as you’d expect from an early 1930s German camera maker. The all brass body, lens, and shutter is very dense and heavy, combining for a total weight of 615 grams, which is right in the middle of the Leica Model C (530 grams) and Contax I (702 grams) in my collection.

The leather body covering on this example is in exceedingly good condition, and is still soft and grippy, just as you’d expect a genuine leather covered camera to feel. The bellows that protect the film compartment as it opens are still light tight, and pressing the little button to erect the front of the camera results in a swift and strong pop as the lens board reaches it’s full open position. This is a well built camera with good size, excellent feel, and a really attractive design.

Up top, the Peggy has an unusual control layout. Although the camera supports normal 35mm film, it was made in an era before Kodak standardized the Type 135 cassette that we all know today. Cameras of this era often used cassette to cassette transport and lacked the ability to rewind the film. The large knob on the left side where a rewind knob would normally be is actually the film advance. The film advance only turns in one direction, clockwise, and has a lock to prevent you from turning it the other way. The large diameter and knurled edges of this knob make it very easy and quick to advance film from one exposure to the next.

A raised portion for the main viewfinder is physically separated from a second raised portion housing the rangefinder. A metal clip that looks sort of like a sideways accessory shoe sits in between the two. I cannot tell if this is some sort of connection point designed for some accessory designed for the Peggy or not, but it sure looks like it.

Behind the rangefinder is the exposure counter which is additive, showing the number of exposures taken on a roll of film, Immediately to it’s right is a small wheel for manually resetting the counter. Using the reset wheel is a bit awkward as you must push forward on it while rotating it counterclockwise. This is difficult because of it’s cramped location immediately behind the raised part of the rangefinder. I often forget to reset manual exposure counters on older cameras, so this likely wouldn’t be a huge issue for me, but for anyone who wants to know how many photos they’ve taken on a roll, this won’t be your favorite part of using the camera.

Next to the exposure counter reset is the shutter release. The shutter release is externally threaded for what has become known as the Leica style cable release. I am sure back in 1932 people didn’t call it that, rather that’s just how cameras were, but it is not compatible with the common style of cable releases which screw into a hole in the center of the button.

Back up on the raised portion on the right is a small circle which to someone first handling this camera might think is the shutter release, but it as actually the film cutter. Like the Ihagee Exakta, which was designed for cassette for cassette film transport, the Krauss Peggy II uses a blade to cut out the film at the end or in the middle of a roll in case you want to take some film out without finishing the current roll. Back when this camera was created, the idea of rewinding film back into it’s original supply cassette was not universally supported. Next to the film slicer is a focus wheel with a depth of field scale on top. Turning this knob moves the entire shutter and lens plate back and forth, very similar to the design of the Certo Dollina series. Like the film advance wheel, the focus wheel has a large diameter and is easy to grip with the knurled edges. Focus distances from 0.9m to infinity are marked.

The rounded edges of the body give the sides of the Peggy a rather symmetric look. Curved edges wrap around from front to back without any hinges or seams to break up a single piece of leather covering the entire body. The Peggy lacks any sort of strap lugs, which means using a neck strap requires either the original leather case or some kind of tripod socket attachment.

Around back, you can see the openings for both the viewfinder on the left and rangefinder on the right. Unlike most 35mm rangefinders with two windows, the rangefinder window is on the complete opposite side of the camera, making it a bit awkward for focusing. The location of the two windows are too close together to use both your left and right eyes at the same time, so assuming you just use the same eye for both, it can be a little strange to have to move your eyes so far to switch between the two windows. At the very least, it does give the rear of the camera a sense of symmetry however. On the body, is a nice embossed Peggy logo as was common with German cameras of the day like the Kodak Retina.

The bottom of the camera has both the film compartment lock and the 3/8″ tripod socket. It was common until about the 1950s for many European cameras to still use the larger 3/8″ threaded tripod sockets. If you wanted to use this camera with a modern 1/4″ tripod, you’d need an adapter. The film compartment lock is the familiar flip up and rotate style with marks for A (open), and Z (closed). Although the Peggy looks like it should be a bottom loader like a Leica, the bottom of the camera is connected to the main part of the body, so sliding the bottom off also takes with it the sides, revealing the entirety of the film compartment similar to the Voigtländer Vitessa and Braun Paxette.

I found that sliding the back and bottom off this camera to be a bit difficult. After removing the back, I could see a large number of scratch marks where the black enamel had worn off two shields that protect both the supply and take up chambers. Although this particular camera is in impressively good condition for a 90 year old camera, it is showing it’s age in this regard. If you find yourself with a Peggy like this one and find that the back is difficult to open, just take it slow and be careful.

With the back off, you’ll see that the film pressure plate is hinged at the top and must be swing up in order to load and unload film. Film transport is right to left, opposite of what we would come to expect from most 35mm cameras. A fresh supply of 35mm film goes on the right and either another cassette or take up spool on the left. As mentioned earlier, the Peggy is designed to transport film from cassette to cassette, so there is no standard take up spool. In 1932 when this camera was made, 35mm film was still considered cinema (or kine) film, and although the film itself was standardized, the cassettes weren’t. Leica cassettes were slightly different from the ones Kodak would later make and the ones Zeiss-Ikon would make for the Contax.

I am uncertain of the exact kind of cassettes the Peggy was designed for, but I found I was able to use the inner core of a regular 35mm cassette for the take up spool, however it needed to be mounted upside down of how it would normally go in a camera. Since the supply cassette goes on the right, the little nub that sticks out of one side of the cassette faces up. For the take up spool, the nub needs to face down. If you attempt to put in the take up spool with the nub facing up, it won’t be able to engage the film advance fork. In the image to the left, you can see how I have a film cassette in the right side of the film compartment (in the image the camera is upside down), and an empty inner spool is on the left, with the nub facing out. This is the only way I was able to get the film to correctly transport over the film gate without it going crooked. Using whatever cassettes were available in 1932 would likely be a better choice, but obviously are much harder to find today.

Another uncertainty of the Peggy’s design are two removable metal shields that wrap around both the supply and take up sides of the camera. When I first received the camera, I didn’t realize these shields came out. Both shields ride on a track to the sides of the film gate. The supply side shield simply slides down, however there is a lock on the take up side that you must release before sliding the shield off. The lock is on the base of the film gate near the track. After removing the shields, make note of which one came from which side as they are not the same and can only go back in the side they came from. Without an English language manual available online, I cannot be sure of the exact function of these shields, but I suspect they offer additional light protection when loading film on spools without a cassette. I can confirm however, that a normal 35mm cassette fits with the shield in place, so I can’t honestly think of a reason why you’d ever need to remove them.

Edit: Since writing this review, I came across a second, chrome Peggy I which still has two original film cassettes in the film compartment. With the cassettes, this other Peggy was missing the metal shields that the black Peggy had. I am uncertain if there were revisions to the film compartment throughout the camera’s life, or if G.A. Krauss designed the camera with more than one way to load film. That this camera came out before Kodak’s standardization of 35mm film, I think this second explanation makes sense. At the very least, we can see that even with the original cassettes, they are inserted into the camera offset, with the supply cassette higher up in the camera than the take up cassette.

Up front, the first control you’ll want to familiarize yourself with is the lens and shutter release tab to the left of the shutter. In the shape of a vertical bar, press in and towards the left on this bar and the front of the camera will pop open to its fully erect position. When it is time to close the camera, simply press in on both sides of the shutter until the front locks into position.

The Peggy II uses a standard Compur leaf shutter, so the controls should be familiar to anyone whose ever seen one of the millions of Compur shutters out there. Shutter speeds are controlled with a ring around the rim of the shutter and have speeds from 1 second to 1/300 plus T and B. Above the shutter is the manual cocking lever which must be done in a separate step before firing the shutter at any of the instant speeds. On early Compur shutters like this one, both T and B modes can be activated without first cocking the shutter first. Simply press on the shutter release with the speed selector in either T or B position to open it up. An interlock exists which prevents you from choosing either T or B with the shutter already cocked. To the right of the shutter is the aperture selector lever with f/stops from 2 to 16. The shutter on this camera offers no flash sync or a self-timer.

Like both the Leica and Contax rangefinders of the early 1930s, the Krauss Peggy has separate windows for the viewfinder and coincident image rangefinder. For anyone who has never used a camera with separate viewfinder and rangefinder windows, this likely seems archaic and slow. While it can be a bit slower, it does offer a practical advantage to that of combined image rangefinders which is that the rangefinder window can be of a different magnification than the viewfinder window. When the rangefinder patch is part of the main viewfinder, it must be of the same magnification, otherwise the two images won’t overlap. By magnifying the rangefinder image more than the viewfinder, you can see the focused image with greater precision, helping achieve more accurate focus.

I mentioned earlier that the locations of the viewfinder and rangefinder windows on opposite sides of the camera is a little awkward, but other than that, they work as you’d expect. The main viewfinder window on this example was crystal clear and easy to see all four edges, even while wearing prescription glasses. The rangefinder window had a bit of haze, but there was still enough contrast with the yellow rangefinder patch that I was still able to see focus in all but the darkest shooting conditions. As you might imagine with this being a 90 year old camera, there’s no other features in the viewfinder such as frame lines, parallax correction, or exposure information.

The Krauss Peggy is a mixture of familiar and not so familiar. If you’re used to 1930s German 35mm cameras, there’s enough here that you should be able to pick one up and figure it out pretty quickly, but there’s also enough uniqueness so that for those of you who like quirky cameras that offer a unique shooting experience, you should be happy as well. It is clear that this camera was designed in an era which the standard for what a 35mm camera should look like and how it would operate, but I am happy to say that they got more right than wrong. Of course, what good is the most well designed camera if it can’t make good photos, so can it? Keep reading…

My Results

Shortly after picking up the Peggy, I was really eager to shoot it. Initial tests of the camera suggested that everything was in tip top shape. The shutter was snappy and fired at all speeds, the Schneider lens looked really clean with only typical signs of use, but no haze, fungus, or major scratches, and the rangefinder focused accurately on things at infinity. This camera is in such good shape, I feel as though it may have had a recent CLA, but unfortunately, I am no longer able to ask the previous owner more about it’s history. All I know is that I loaded in a roll of fresh Ferrania P30 and took it with me on a trip to Northern Minnesota and Madison, Wisconsin.

For starters, although I have shot Ferrania P30 before, I am always amazed at it’s unique looks each time the images pop up on my scanner. Skintones take on a much darker shade than other black and white films, and in some outdoor shots, bright, washed out skies can occupy the same image as muddy darks. I won’t deny tweaking a few of these images in post processing, however I do like the look. In fact, pairing a high contrast black and white film with an uncoated prewar lens which has a tendency for low contrast can balance out the image and produce unusually good results.

And “unusually good results” I think is a good description of these images. They’re not perfect, but wow, I was not expecting such nice images. I’ve shot many Schneider Xenons before on Kodak Retinas, Exaktas, and other German cameras, but the results from this uncoated prewar lens blew me away. Sharpness and rendering on some of these images is like an even combination of digital clarity with a softness that only a 90 year old lens would produce. I can’t explain it other than to say I love these images.

mikeeckman.com Trivia: This is the first review I’ve published that includes scans from my new Epson V750 flatbed scanner. Previously, my scans were done on an Epson V550 with lower resolution. I believe that the V750 does a better job of extracting detail than my old scanner did.

Prewar uncoated or postwar coated, Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon lenses are some of the best out there. Sharpness is excellent in the center and extends almost completely to the corners at which point it dips ever so slightly. Contrast in the images from already contrasty film is excellent, as is the lens’s ability to resolve fine detail and details in the dark. One trademark of uncoated lenses is how light can bounce around inside the lens causing halos to appear around bright light sources, none of which I see here. I did overexpose a couple shots here, namely the one of the boat and pier, but there was still enough detail to where I could pull it back in Photoshop. Quite simply, these images are stunning.

Using the Peggy was a lot of fun too. The strange thing about German 35mm rangefinder cameras from 1932, is that they’re all very different. The Leica, Contax, and Peggy are all VERY different. The Peggy being the lowest featured camera, it is no less a high quality camera deserving of being mentioned with those other two. In fact, the use of a Compur leaf shutter as opposed to the complex vertical shutter of the Contax or the fragile cloth curtains of the Leica, I believe that finding a Peggy in working condition should be easier, and if one is found with an inoperable shutter, repairing a leaf shutter is way easier (and cheaper) than those other two.

Functionally, this Peggy II was in excellent condition. I mentioned in the section above that I suspect this camera has been serviced recently, but I cannot prove it. Everything about the camera worked great with the only issue being a slightly hazy rangefinder. The rangefinder proved to be accurate for focus, but the haze did make it difficult to see in low light, otherwise, there were no functional issues using this camera.

One of many reasons the Leitz Leica was so successful is that it has almost perfect ergonomics. The camera is compact, fits well in the hand, and all of it’s controls are logically placed and easy to reach. I can’t say the same about the Peggy. While the body does have similarly curved edges and does feel good in the hands, the various parts of the camera are not as nicely laid out.

The most egregious example is the rangefinder window. Located on the complete opposite side of from the viewfinder, it is incredibly awkward to not only have to move your eye so far from one window to another, but that how you hold the camera with the viewfinder on the left and on the right is different, and I found it to be very awkward to move my face, without completely repositioning how I was holding the camera. In many of these reviews when I point out an ergonomic ‘snafu’, I usually say that with repeated use, you’d probably get used to it, but I don’t think that’s the case here. Anyone in 1932 that might have held a Contax, Leica, and a Peggy, I imagine that they would all have found the Peggy’s layout to feel strange.

Next is the shutter release. Although it’s location is in close proximity to where it is on the Leica, the Peggy’s shutter release is on the lower portion of the top plate behind the rangefinder, which requires you to contort your finger over and behind the rangefinder “hump”. I have averaged sized hands and although I was able to reach the release, it wasn’t comfortable, and each time I would put the camera to my eye, there was always a delay while my finger searched for the release. The hump also impacts the exposure counter reset wheel, but I already covered that in the section above.

Finally, one last issue, which is more a result of the era in which the camera was made, the Peggy came out before the standardization of 35mm cassettes. Loading film is a bit awkward. This example did not come with any original spools, so I am not sure how it should be, but I found that using replacement spools required a bit more fiddling to make it work, but once I got it, I had no other issues with film transport.

This might seem like a long list of gripes, so I’ll say not all is bad. I really liked the location and use for the top plate focus wheel. It reminded me of the location on back wheel focus cameras like the Voigtländer Vitessa and is very intuitive to use. The film advance wheel is large and very easy to turn, extending the camera for use is a snap, setting shutter speeds and f/stops is no different than any other leaf shutter camera, and of course, getting properly focused and good looking images was very easy. Looking at my first roll of Ferrania P30, not a single image was out of focus or improperly framed. I really did enjoy using this camera. It’s quirks are definitely worth mentioning in this review, but none of them were dealbreakers, and for people like me who enjoy using old cameras, the Peggy II is a lot of fun!

For most people, the only two options for early 1930s German rangefinder cameras were the Leica and Contax, but I think the Peggy is deserving to be mentioned in the same discussion as those, even if the feature set doesn’t perfectly match. I love the unique looks and feel of this camera, had a lot of fun shooting it and most important, got some amazing shots. If you have a chance to pick up or shoot a G.A. Krauss Peggy II, I definitely recommend it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Peggy

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/appareil-5558.html

https://www.photo.net/forums/topic/473276-anybody-an-expert-on-the-krauss-peggy-norm/

Спасибо! Как всегда – познавательно и любопытно!

Thank you! As always – informative and interesting!

Mike, you might try to use Agfa Rapid cassettes in this camera. They might fit.

Sadly, the big mystery remains unsolved: Who was Peggy? And how did she get a family of cameras named after her?

You would think I had heard of this camera, but no. It was slightly surreal to real it and have the name Peggy mentioned so much…it isn’t a common name and I rarely hear it in any other context other than myself. Thank you so much for introducing me to this camera.

Well, reading that post was a bit surreal. I rarely hear my name mentioned in any other context and here is a full on post about a camera with the same name as me. Thank you for introducing me to this rare and expensive namesake. 🙂

The Schneider Xenon f:2 4,5 cm lens Serial number 565062 was engraved on 8 May 1933. In other words, the camera did not leave the Kraus factory until after this date…. perhaps you need to change the date of (1932) to (1933) for a bit more accuracy.

Thanks for the info David. While you are correct that this specific camera was likely made in 1933 or later, I indicated 1932 as that’s the year the Kraus Peggy II was introduced. I do it this way on most of my reviews, like for example in my review for the Nikon S2 which was introduced in 1955 or the Pentax K1000 which was introduced in 1976. I do not indicate the year my actual example was made as that is often very hard to find out. Only cameras with date codes imprinted somewhere on the body like many Soviet cameras, or Leica cameras which have very good well documented production dates, I rarely list the year of the actual camera.

I see on several websites that the winding knob should have a secret compartment containing a yellow filter. Looking at yours that might not be practical with a screw going right through the middle. But the winding knob certainly looks large enough to be able to contain it. Have you checked it out?

Here for example: https://www.flickr.com/photos/camerawiki/48717853161/