This is an Ilford Witness, a 35mm rangefinder camera made in 1953 by Peto Scott Electrical Instruments for Ilford of London, England. The Witness was a very ambitious camera, first designed in 1947 by ex employees of Leitz and Zeiss-Ikon. It incorporated a unique hybrid screw/bayonet lens mount, focal plane shutter capable of up to 1/1000 and a combined coincident image rangefinder in a sleek and attractive body. Four years would pass before a working prototype was produced and another two more before the camera went on sale. When it finally did, production delays, poor marketing, and a feature set that was no longer as innovative as when the camera was first designed, doomed it. The Ilford Witness was available only for a short time and less than 350 are thought to have been made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 2″ (50.8mm) f/1.9 Dallmeyer Super-Six Anastigmat coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Ilford Witness Combined Screw/Bayonet

Focus: 18 inches to Infinity (3 feet to Infinity rangefinder coupled)

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and Adjustable 0-30ms Flash Sync

Other Features: Adjustable Flash Sync

Weight: 774 grams, 608 grams (body only)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/IlfordWitnessManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Ilford Witness is a very rare British camera that when it was being designed aimed to be a viable alternative to both the Leica and Zeiss-Ikon Contax, combining elements of both cameras into a single, high quality, interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder camera. Although the camera was unsuccessful with only a very few made, it did meet the goals of its design as the Witness truly is a remarkable camera with good ergonomics, some clever features, and a gorgeous design. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 13.0 | ||||||

Prologue

If you are a regular follower of this site, you may be thinking, “Gee Mike, didn’t you already review the Ilford Witness?” Yes, I have previously written a review about this camera when I had a chance to handle one for a couple of minutes from the Voncabbage Collection back in 2021. Being a camera in which only about 350 were ever made, I took that opportunity, as short as it was, to take a few poorly lit images of the camera and type up a review based on what I could remember in the five minutes I handled it. I never got a chance to shoot that camera, but assumed that I would never get a chance to shoot one, so I did the best I could with the review.

Fast forward to January 2024 when I was contacted by a reader of this site named Al Harrison who had told me that his father had bought an Ilford Witness when it was new and remained his personal camera until he passed away a few years ago. Al said that before his father had died, he read my original review of the Ilford Witness and was happy to learn about the history of the camera.

After the elder Harrison passed away, his son talked to the rest of the family to decide what to do with the camera and the choice was made to sell it. Not knowing who best to sell their dad’s beloved camera, Al reached out to me, and I’ll just spare you the details, but now I have the camera. This camera will soon go to Dan Tamarkin who will auction it off with the proceeds going back to Al Harrison and his family, but for a few short months in the summer of 2024, I had the Ilford Witness with more time to photograph it and shoot some film through it.

This review consists of some of the same historical info from the original, but with all information about its use, new photos of Al’s camera, and sample images I got with it.

History

Mention the name “Ilford” to any film photographer today or from the past 100 years and they’ll likely tell you about one of the company’s excellent black and white films. Emulsions like HP5, FP4, and Delta have lineages that go back nearly a century and along with Kodak, Fuji, and AGFA are one of the most respected makers of photographic film in the world.

What fewer will think of were the company’s short lived forays into making cameras. Like most other makers of film, Ilford was a film first company. At various points in their history, whenever a camera was made bearing their name, it was likely sold to help generate more customers for their film. The thought was that the more people who owned an Ilford camera, the more people might buy Ilford film.

The origins of Ilford date back to a studio photographer named Alfred Hugh Harman who in the 1860s specialized in calotypes and other artificial light photography. In 1879 Harman would abandon his studio and started making photographic gelatine plates in the basement of his home. Initially doing all the work himself, Harman eventually hired staff to help him keep up with the demand from the quickly growing photographic industry.

In 1883, Harman expanded to a larger location in East London where he could grow his business. The company operated under the name Britannia Works and in 1891 became a publicly traded company. The company would rename in 1898 as The Britannia Works Limited and once again in 1900 to Ilford Limited, a name taken from the the town the company was located in.

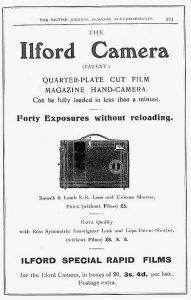

Shortly after the turn of the century, Ilford’s business continued to grow, and in 1902 released its first camera, the Ilford Falling Plate Camera. This simple device, in the shape of a wooden box, used the company’s quarter plates and was advertised as being able to shoot 40 exposures without reloading. The camera came with a variety of lenses made by companies like Ross and Bausch & Lomb.

Over the next couple of decades, Ilford’s business continued to prosper. By the start of World War II, the British government declared Ilford to be essential to the war effort, providing necessary aerial reconnaissance supplies. It was classified by the war department as a Scientific Instrument Maker and munitions factory. This allowed the company to receive prioritization of raw materials and other types of economic protection.

With Germany’s participation in World War II, photographic cameras and other supplies from Germany came to a screeching halt. Companies from all over the world scrambled to fill the void of Leica cameras and Zeiss lenses that were no longer available.

Around 1947, Ilford took the charge to built England’s finest 35mm camera, a model that would compete with or exceed the high quality mark set by cameras like the Ernst Leitz Leica and Zeiss-Ikon Contax. To help them take on such an ambitious project, Ilford hired two former German/Jewish employees of Leitz and Zeiss-Ikon, Robert Siegmund Sternberg and Werner Julius Rothschild.

Both Sternberg and Rothschild started working on a new interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder camera that would take the best of both the Leica and Contax, and create an entirely new camera from the ground up. From the Leica, it would support the 39mm Leica Thread Mount, but from the Contax it would also feature a hybrid bayonet mount. From the Leica it would have a traditional beamsplitter using mirrors instead of glass prisms which added complexity to the Contax’s design. But like the Contax, the distance between the viewfinder and rangefinder window would match that of the Contax, allowing for greater precision, especially while using telephoto lenses. Initial development on Ilford’s new camera was slow as it would take three years before any prototypes were shown.

Early examples of Ilford Witness prototype cameras and lenses were manufactured by Rothschild’s company, Northern Scientific Equipment Ltd as Ilford lacked the equipment to build them. Production of the cameras at NSE was very slow and caused further delays in mass producing the camera. It would take another two and a half years before the first models were available for retail sale in late 1952.

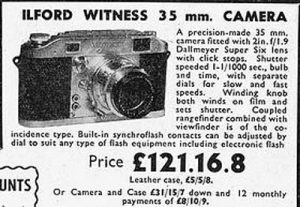

The ad to the left from April 1953 showed the Ilford Witness for sale with a price of £121.16s.8d, which according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, compares to about £2700 today. That price, converted to USD compares to just under $5000 today, a monumental price for an all new camera from a company only known for its film.

In addition to its high price, in between the time when the camera was first conceived in 1947 to when it was actually available, the camera industry had changed wildly. For starters, the German camera industry had recovered and imports of German cameras were easy to get, but also the dawn of the Japanese camera industry had already started trickling in well built and reasonably priced alternatives, making a premium British camera a tough sell.

Sales of the Ilford Witness were extremely poor with less than 350 thought to have ever been made. It would seem that the failure of the camera was already apparent to Ilford before its release as the company had already started investing in much simpler and less expensive cameras like the Ilford Advocate and Envoy box cameras.

Production of the Witness ended in 1953 with remaining inventory sold by local photographic retailers for as low as £80 each.

Over the next couple of decades, cameras with the Ilford name would continue to be made, but none with anywhere near the quality or features as the Witness. Production of most Ilford cameras was outsourced first to OEM German manufacturers and later Japanese makers. Single use cameras with the Ilford name and loaded with one of the company’s current black and white films can still be bought today for slightly more than the price of a single roll of film, making them ideal for those curious about film and wanting to try it for themselves without having to invest in expensive used equipment.

Today, cameras like the Ilford Witness are hard to categorize. Normally I would describe them as highly collectible, but their rarity and extremely high prices make them nearly impossible to find. With prices as high as $15,000 in the used market and less than 350 ever made, only the most deep-pocketed collectors have one, and rarely put them up for sale.

Still, with their gorgeous design, long list of features, and historical significance, if you ever have the opportunity to be in the room with an Ilford Witness, I definitely recommend it as there truly was never another camera made like it.

My Thoughts

Having the chance to handle one Ilford Witness was special, but to handle two, and then shoot the second one? Sign me up! This camera came to me by way of site reader Al Harrison when he contacted me about helping him sell his father’s camera. Al is located in the UK and after multiple back and forth emails, he and I agreed that this camera would go to Tamarkin Auctions, but before that, I’d have a couple months to shoot some film in the camera and give it a proper review.

Al said this camera was bought by his father brand new in the early 1960s and was his primary camera for over 30 years. He went onto to say that most of his childhood memories were captured using this camera and he has fond memories of seeing his dad using it for so long. When Al’s dad passed away, the camera sat idle while the family decided what to do with it, and when the time came to get rid of it, he contacted me after reading my previous review of the camera and the rest is history.

When I handled the first Ilford Witness that I photographed for my original review, I had less than 5 minutes with it and I don’t have a lot of memories of what it felt like. Surely the camera was meant to compete with the Leica and represented the best of what Ilford could do at the time, so when I received this second one, I was eager to spend some time with it and see how well it was built and how it worked.

This Witness saw regular use for over 30 years and as a result, shows signs of heavy use. There are various dings, scratches, and other imperfections all over the camera. However, something I’ve commented on this site and on the Camerosity Podcast many times, cameras that show the most signs of use usually have a better chance of still working as opposed to a mint condition shelf queen that has never been used. Consistent with that belief, the Ilford Witness worked perfectly. The shutter fired at all speeds and sounded accurate to the ear. The viewfinder was clear and the rangefinder accurate. The lens had some dust and maybe the tiniest bit of haze, but otherwise still looked to be in very good condition.

For any camera to survive 60+ years with over 30 years of continual use and still be working should suggest the build quality is quite high. Despite its age, the Ilford Witness still had a feel of a quality camera, the knobs and buttons and turned and moved as they should with minimal slack. The focus helix moved smoothly without grip and I found the action of the shutter to sound as good as any German or Japanese camera from the same era. The chrome plating was deep and showed minimal signs of wear without any oxidation as you might expect on a more cheaply built camera. Looking inside the film compartment where even some of the most luxurious cameras can sometimes show some shortcuts, the Ilford Witness had no sharp edges, obvious machining marks, or exposed internal parts. Clearly, the Ilford Witness was built to a very high quality standard.

Up top, the camera has a very sleek look with all controls sitting flush with the top plate. You can rest the camera upside down on a flat surface without it tipping over. On the left is a small pop up rewind knob. The knob sits behind an angled wall which transitions to the rest of the upper plate, partially obscuring it from the front of the camera, further adding to the sleek look of the camera. In the middle is the stylized Witness logo and behind it an accessory shoe which is covered by a spring loaded plate. To attach a flash or meter to the shoe, press down on the chrome plate and you can slide in your accessory just like any other camera. I don’t know that this serves any useful purpose other than looking cool.

To the right of the shoe is the shutter speed dial, which continues the sleek design of the camera being fully flush with the rest of the top plate. Settings for shutter speeds from 25 to 1000 are here, plus one more setting marked B.T which relies on the slow speed dial on the front of the camera. To use slow speeds on the front dial, turn the dial to the position marked ’25-1′ and then you have additional options for speeds from 1/25 down to 1 second. To shoot in either B or T mode, set the dial to the ‘B.T’ position and turn to ‘B-25’ for Bulb and ‘1-T’ for Timed. Due to the sleek design of the shutter speed dial, you can only change speeds by sliding your finger over the back edge of the dial.

Next to the shutter speed dial, on a lowered platform is the cable threaded shutter release button and then on an even lower platform is the combined film advance knob and exposure counter. The counter is additive, showing the number of exposures made on the current roll of film and must be manually reset after loading in a new roll of film. The Witness user manual suggests that the film can be quickly advanced by using your index finger to slide it along the edge of the advance knob, giving it one full rotation. I experimented with this and found that it worked unexpectedly well.

Flip the camera over and the base has two rotating keys for opening the film compartment. The design of the keys is very similar to those from the Zeiss-Ikon Contax in which you fold out the half-circle shaped handle and rotate it 180 degrees. In the center is a 1/4″ tripod socket which helps balance the camera while sitting on a tripod.

The sides of the camera are the same with only a metal strap lug on both sides. The strap lug is part of the body structure and is of the kind where over time it can wear away, thankfully that doesn’t appear to have happened on this example. From the side of the camera, you get a good look at the design of the Dallmeyer Super-Six Anastigmat lens which looks like it is collapsible, but it is not.

Around back the only things to see is the rectangular eyepiece opening for the viewfinder and on the right, below the film advance knob, is a film transport switch for rewinding film at the end of a roll. With the switch in the “W” position, film transports normally, and in the “R” position the transport is deactivated so you can rewind the film. The back of the door shows the leather body covering which is missing from the front of this camera. The leather shows some ‘Zeiss bumps’ beneath due to brass corrosion, but otherwise is still in good shape.

With the back of the camera removed, the film compartment is another area of the camera which clearly takes some cues from the Zeiss-Ikon Contax. Film transports left to right onto a removable take up spool. If you do not have the original spool which came with the camera, the inner plastic spool from a regular 35mm cassette will work. The Ilford Witness supports cassette to cassette film transport or you may use a regular film take up spool and rewind your film at the end. The film gate has two unpainted metal rails above and below it, with the camera’s serial number engraved beneath. Inside the film door is a squarish metal pressure plate and is held in place by two clips on each side. While not exceptionally big, it feels like a solid piece of metal that will do its job without issue. The film compartment lacks any sort of light seal material in the upper channel or along the edges.

On the inside of the bottom of the door is a gold foil sticker for John Frost Photographics in Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, which may be where the camera was originally purchased. A quick Google search for “John Front Photographics Birmingham” reveals a news article from June 2023 which sadly announced the closure of the photographic shop which had been in business since 1934.

The most unusual feature seen in the film compartment is a black metal dial on the bottom of the film gate which sets a variable flash sync delay from 0 to 29 milliseconds for various types of flash bulbs. On page 15 of the camera’s user manual is a chart showing the sync delay for various types of Philips and GE flash bulbs that were probably available at the time the camera was made, plus one more for electronic flashes. The sync delay changes depending on what speed film you are using, which is probably why this setting is inside the film compartment, forcing you to use the same delay for an entire roll of film.

Looking down upon the top of the Dallmeyer Super-Six Anastigmat lens, closest to the body we see an engraved depth of field scale. In front of it is the focus scale in feet from 18 inches to infinity. The Dallmeyer lens is dual range with a transition near the 3 foot mark which corresponds to the end of the rangefinder coupling. Under normal use, you focus the lens between 3 feet and infinity using the coupled rangefinder. For close ups, you can go closer than 3 feet, but must first press a button on the focus arm to get it past the transition and focus down from 3 feet to 18 inches. Once you go past this transition, the rangefinder coupling is disengaged, so you will not be able to use it. Nearest the front of the lens in front of a large expanse of lens barrel is the aperture ring with f/stops from f/1.9 to f/22. The aperture ring is on a part of the lens that rotates as you focus the lens, so depending on what distance the lens is set at, the aperture scale may not be facing up. Dallmeyer wisely engraved two different aperture scales on opposite sides of the lens but it is still something you can’t always see.

Up front, the Ilford Witness continues its sleek appearance with a symmetrical layout of the top plate. Both the viewfinder and rangefinder window are on opposite sides of the front face and the black body which should be covered by leather is even on both sides of the lens plate. Near the 10 o’clock position around the lens is the slow speed dial and near the 8 o’clock position are two flash sync ports which are both used for a specific type of flash gun made for this camera. The letter “E” next to the bottom port indicates this is grounded to the camera body for electronic flashes.

Near the 9 o’clock position around the lens is the bayonet lens release which is used to remove the Dallymener Super-Six Anastigmat lens or any other lens made specifically for the Witness. A curious feature of the Witness is that it has a dual lens mount which Ilford referred to as an ‘interrupted thread mount’ in which the bayonet mount is internally threaded to also accept M39 Leica Thread Mount lenses. This feature was added to expand the available lenses that would work to include those made for the German Leica. If a photographer who already owned a Leica and some lenses was looking to upgrade their camera, they would be more likely to consider a new British camera if it worked with their older lenses. Unlike the Zeiss-Ikon Contax in which there are two separate bayonets, the Ilford Witness uses the same mount for both bayonet lenses and screw mount lenses.

In the three images above, you can see screw threads on the inner surface of each bayonet and a staggered arrangement of threads on the inner lens mount. This means that you can swap the Dallmeyer lens with any M39 mount lens by Nippon Kogaku, Carl Zeiss, Leitz, or any of the other zillions of screw mount rangefinder lenses made in the 20th century and still use the coupled rangefinder. The third image shows the Witness with a Nikkor 5cm f/2 off a Nicca rangefinder. Even sweeter, the Dallmeyer Super-Six Anastigmat can also be mounted to a M39 LTM camera, or if you wanted to try shooting it digitally, it would work with any regular M39 adapter!

The Witness viewfinder is very typical of an early 1950s 35mm rangefinder camera with a decently large blue tinted main viewfinder window and a square rangefinder patch in the middle. The rangefinder patch is tinted pink which gives it good contrast compared to the rest of the viewfinder. Looking at the design of the rangefinder, the base length of the two windows appears to be very similar to that of a Contax IIa and IIIa. I didn’t have a ruler handy, but looking at the cameras side by side, the distance appears to be the same 73mm, meaning rangefinder accuracy would have been quite good with telephoto lenses.

No frame lines or any other information regarding exposure are visible. A curious characteristic of this camera is that while firing the shutter, a horizontal pin briefly appears in the center of the rangefinder patch and quickly disappears. This looks to be like some internal part of the viewfinder gets in the way of the light path confirming that the shutter has fired. This is not mentioned in the Witness owner’s manual, so I am unsure if this is an intentional feature, or is a side effect of how the camera works.

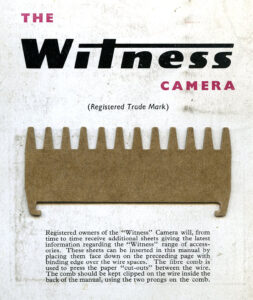

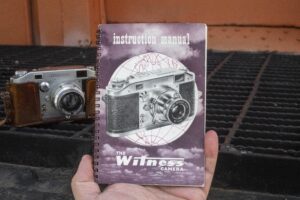

One final interesting element to owning an Ilford Witness comes from something I rarely talk about, which is the camera’s owners manual. The Witness would have originally come with an 18 page paper manual with a spiral binding, like you’d see in some scholastic books. Originally, I dismissed the spiral binding as a curious design choice, but after opening the manual, I found this strange cardboard comb pressed into the spiral loops near the end of the manual. The purpose for the comb was not immediately clear, but its location inside the manual left imprints on the pages next to it suggesting that it had been there for a very long time. I didn’t spend much time thinking about the comb until I noticed a small blurb of text near the bottom of the rear cover of the manual explaining its purpose which was to spread apart the metal spiral binding to add additional pages to the manual that Ilford had intended to send to registered owners of the camera. I am unsure if Ilford ever made additional pages, but this text suggests that they had planned on adding additional accessories to the Ilford system, had it been more successful. With no additional pages, this comb never served any purpose, but I found it to be a really neat bit of insight into a camera system that never was.

While handling the Ilford Witness, I couldn’t help but be impressed. This may have been a very low production camera that didn’t sell well, but you’d never know simply by handling it. If you were to show this camera along with a couple other early 1950s rangefinders to someone not familiar with old cameras, and ask them which was the one that sold the poorest, I doubt they’d be able to pick the Ilford Witness based solely on its design and ergonomics. Of course, a well designed camera is fine for a shelf queen, but what if you want to use it? Keep reading!

My Results

Eager to put to test one of the most unlikely cameras I’ve ever had a chance to shoot, I thought it would only be appropriate to shoot an Ilford camera with Ilford film…except I didn’t have any at the time and didn’t want to wait, so for my first roll through the Ilford Witness I chose the next best thing, Kentmere 400, which is made by Harman who also makes most of Ilford’s current films, so I thought, hey why not?

Intrigued by the first roll, it was clear the rangefinder was accurate and the shutter was close enough to get accurate exposures at all the speeds I shot it at, the only flaw I saw were a couple light leaks in a couple images. Knowing full well I’d likely never get another chance to shoot an Ilford Witness, I taped up the door seams and loaded in a second roll, this time of fresh Fuji 200 and took it for another spin.

The images from the color roll of film were as good as the ones from the black and white, except despite putting tape on the teams to eliminate the light leaks I saw in the first roll, they persisted. Shooting color film on a camera with light leaks is beneficial to black and white as depending on the color of the light leak, it can help narrow down where it is coming from. With color film, an orangish red light leak means it is coming from the film compartment as the light is passing through the brown base layer to the emulsion, causing the orangish red leak. However, if the leak is white, this means it is directly hitting the emulsion side from the front.

Light leaks from rotted out door seals are easy enough to fix, but white leaks from the front of the camera are harder to track down and that’s what I was seeing with this camera. The good news is that they didn’t affect every image I shot, so I was able to still pick several sample shots to share.

The 2 inch f/1.9 Dallmeyer Super-Six lens rendered nice shots with a tad bit of softness, but in the best way possible. The images from the Ilford Witness remind me very much of those shot with a Leitz Summitar. I do not know the exact makeup of the Dallmeyer lens, but the similar era in which both lenses were made, I would not be surprised if there wasn’t at least a few similarities in the design of both.

Sharpness was excellent across the frame with just the right amount of softness in the corners. I got accurate colors, especially in doors, suggesting the primitive lens coating was still doing its job. Although an incredibly rare lens, it is clear that the Dallmeyer delivered the goods, at least as good as anything on the market at the same time this camera would have been sold new. My only regret is that I didn’t take the opportunity to shoot this lens digitally while I had it, but unfortunately, the deadline to send it back came faster than I had hoped.

Shooting the Ilford Witness was a surprisingly good experience. For a camera whose development began in the late 1940s, had the camera came out then, it would have been one of the most modern 35mm rangefinders on the market. Even with its release in 1953, the camera compares favorably to Nikon and other screw mount rangefinders. The ergonomics on the camera are really good and the combined image coupled rangefinder was as good as any from the era I’ve shot. A subtle but effective design element of the film advance knob allows you to quickly advance the film by extending your right index finger and while pressing with the side of your finger toward the knob and pulling your finger towards the back of the camera, you can quickly rotate the knob, advancing the film and cocking the shutter in one single motion. I’ve never seen any other rangefinder work like this, but it is really cool and not something I would have thought to try had it not been mentioned in the camera’s manual.

Handling the camera, the Ilford Witness had excellent balance, and the soft curved edges of the body and top plate made it feel very comfortable in the hand. The location of the shutter release was a bit too close to the rear of the camera for my tastes. This location is similar to that of screw mount Leica and Nikon rangefinders, and something I prefer to be more toward the front of the camera, but is hardly a major issue.

Nitpicks are few and far between, especially when comparing this camera to its competition, but it is clear that for as much effort as Ilford put into this camera, by the time it was released, you can see why it sold poorly as it already was equaled or surpassed by a growing number of German and Japanese rangefinders. Despite an attractive design and some minor niceties, it wasn’t any better than what was already out there. Had this camera been released in the late 1940s or even 1950 when the German camera market hadn’t returned to full capacity and there wasn’t the huge influx of quality cameras coming out of Japan, I really think the Ilford Witness could have been a big success.

As it was, the Witness was still a very good camera, but high prices and a dwindling market doomed the camera. Had it come out sooner and been more successful, it likely would have survived in the market longer, possibly even leading to a Witness II, perhaps with a larger viewfinder, hinged film back, film advance lever, and maybe even some kind of built in exposure meter.

I am incredibly fortunate to have had the chance to handle and shoot this camera. It wasn’t in mint condition, but something I say often is that the more use a camera shows, the better of a chance it will still work. Shelf queens almost always are frozen solid and can’t be used, but that this camera had a healthy amount of usage throughout its life and a few battle scars, is likely why it worked as well as it did. I want to thank its owner, Al Harrison, for sending it to me and giving me the chance to shoot it. In an interesting twist, after this camera left my hands, it headed to Tamarkin Camera in Chicago Illinois for their annual camera auction in November 2024 where it will go on sale. If you’d like to own one of roughly 350 Ilford Witnesses ever made and one that still works, be sure to check out the next Tamarkin Auction and maybe this very camera can be part of your own collection!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Ilford_Witness

https://www.photomemorabilia.co.uk/Ilford/Witness.html

https://www.9days.hk/post/ilford-witness-a-masterpiece-rangefinder-1-38/

I wonder if the folks who designed the Vokar 35mm rangefinder took inspiration from the top cover of this Ilford camera. Their profiles are very similar and equally different from most all other cameras of the era.