This is an Imperial Mark XII Flash, an all plastic scale focus camera built by the Herbert-George Company of Chicago, Illinois starting in 1956. The Imperial Mark XII Flash shoots 2 ¼ inch x 2 ¼ inch images on 620 roll film and has a fixed focus, fixed aperture, and a single shutter speed. It was sold as a kit with a detachable flash gun that was synched to the shutter. The camera came in a variety of different colors including red, aqua green, and blue. It was also available in special editions for both the Boy and Girl Scouts of America.

Film Type: 620 Roll Film (twelve 2 ¼ inch x 2 ¼ inch exposures per roll)

Lens: unknown focal length (probably ~75mm), unknown aperture (probably ~f/11), unknown elements (probably plastic meniscus)

Lens Mount: (only when interchangeable)

Focus: Fixed, ~6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Plastic Lens

Shutter: Metal Blade

Speeds: Single Speed, ~1/50 second

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None, 2x Type 915 Penlight Batteries for Flash Gun

Flash Mount: Imperial II Flash Gun

Other Features: None

Weight: 302 grams, 228 grams (camera only)

Manual (Flash Guide): https://cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/imperial_herbert-george_synchronized.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Imperial Mark XII Flash is a typical mid century American build plastic box camera that offered extremely simple operation with good, but not great performance for the customer who just wanted to make images, without any knowledge of photography. This was a simple and attractive plastic camera that came in a variety of colors, which makes it just as popular for those people looking for mid century American design décor as it does people who collect cameras. Whether you just want something that evokes the MCM style, or a mid century plastic box camera to shoot, the Imperial Mark XII Flash is the camera for you! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.8 | ||||||

History

Whenever I start researching the history of a camera for this site, my sources of information vary depending on where it was made and who made it. I regularly revisit the same sources for Soviet, German, or Japanese cameras. There are specific sites with large caches of information for specific models and specific types. I have many different sources for online catalogs that I know contain information for specific cameras from a specific era. I have a couple Japanese language sites that are good for 50s and 60s Japanese cameras. If I need help with Leica, Canon, Nikon, or Zeiss, I have books that I can refer to.

Of all the different brands and places cameras were made from in the 20th century, the one place that I dread doing research on are for cameras made in Chicago. What makes this especially odd is I grew up around Chicago. Not in the city itself, but in the far south suburbs. As a kid, my dad regularly took me to White Sox, Blackhawks, and Bulls games. I’ve been to Northwestern to see a game before, I’ve been to all of Chicago’s excellent museums, and as I got older, visits to Millennium Park, Lincoln Park Zoo, and Central Camera were favorites of mine.

Yet, in the mid 20th century, a so called “Chicago Cluster” of companies produced a huge number of very simple and very similar cameras. Many of the Chicago Cluster cameras were the result of questionable business practices by a former jazz musician named Jack Galter who created a seemingly endless number of companies all producing the same products. If you’ve ever come across a camera with the name Spartus, Utility Mfg, Herold Mfg, Acro, Carlton, Elgin, Clix, Churchill, Champion, or Fleetwood, you’ve seen a Jack Galter product.

Galter wasn’t alone in his Chicago camera making ventures as another man named William H. Grafft did something similar with a large number of inexpensive cameras sold under the names Pho-Tak and United States Camera company. The number of companies credited to Grafft isn’t as numerous as to Galter, but the history of them is shrouded in a similar amount of mystery.

This brings us to the Herbert George Company, yet another Chicago based company that made a large number of cheap, and very simple cameras that appeared and disappeared with almost no trace of what happened. Apart from the existence of cameras claimed to be made by Herbert George, there is almost no evidence that the company existed at all.

If you do a Google search for the Herbert George Company, you’ll likely come across the exact same information over and over again, which is that it was founded around 1945 in Chicago by Herbert Weil and George Israel. The company changed ownership in 1961 and was renamed Imperial Camera Corp. And that’s it. There’s almost nothing beyond this same information cited over and over again. I scoured every resource I’ve come across while researching cameras for this site. I have paid memberships to newspapers.com’s archive of American newspapers from the 20th century, along with a subscription to the New York Time’s Times Machine and I found only sporadic evidence of the company’s existence.

In the November 29, 1961 issue of the Chicago based Suburban Economist newspaper, a Chicagoland business directory listed a large number of what appear to be totally unrelated companies all with the same address of 311 N. Desplaines Street in Chicago. A partial list of those companies is:

- Abbott Rubber Co.

- Grobet File Company of America

- Hill-Shaw Company

- Oscar Leistner Inc.

- Marion Products Co. Inc.

- Reliable Jobbing House

- A G Wire Frame & Novelty Company

- Republic Engraving & Design

It is unlikely that all of these completely unrelated companies all occupied the same space at the same time, but rather were owned by some commercial management or equity firm that invested money into various industries and sold them for a profit. The true identity of the Herbert George Company is likely very uninteresting and lost to history, but what we do know is that the company did exist and somehow, produced a large number of inexpensive, but very similar cameras.

Without much information about the company’s history or fate, I can only conclude that someone had the idea to invest into cheaply built cameras that if sold in sufficient quantity, could return a profit over a period of time when amateur photographers were in the market for simple plastic box cameras. That nearly all cameras credited to the Herbert George Company follow the same basic formula supports my theory. My guess was, that whoever owned this company saw an opportunity and took it, but when the market dried up for cheap plastic box cameras, they pulled the plug.

The Imperial Mark XII Flash being reviewed today seems to have been one of Herbert George’s more popular models as a large number of them regularly show up for sale in online marketplaces, and are still regularly found at garage sales in the United States.

The Imperial Mark XII Flash was not advertised in mainstream photographic magazines like Popular or Modern Photography as the target customer was not someone who took photography seriously. This was a snapshot camera designed for someone who preferred ultimate simplicity over anything else. It wasn’t until I started searching old newspapers for department store or jewelry ads before I found anything mentioning this camera.

The ad above is from the August 29, 1956 edition of The Decatur Daily Review in Decatur, Illinois and shows an advertisement for Walgreen’s Drugs where the Imperial Mark XII Flash was sold for $3.98. I found many similar ads for the camera with prices ranging from just under $4 to $5 at national and local drug stores and jewelry stores.

Sometimes the camera wasn’t even offered for sale, but rather as a giveaway for subscribing to a newspaper or opening a bank account. The ad to the left is from October 8, 1957 and says that if you subscribe to the Chicago Daily Calumet, you’d get the camera (which they proudly proclaim is not a toy) for free!

Using the camera’s retail price of $3.98, when adjusting for inflation, this would have been a $43 value. Not bad for subscribing to a newspaper!

Fun Fact: If you search mid 20th century magazines and newspapers for the term “Imperial Mark XII”, you will find many more results about an RCA Whirlpool washing and dryer combination with the exact same name. I find it pretty funny that both a camera and a washer and dryer combination with the exact same name was sold around the same time!

Like many other Herbert George cameras, the Imperial Mark XII Flash was offered in several different color combinations, including red, light blue, seafoam green, pink, beige, gray and black. Versions made for the Boy and Girl Scouts of America exist as well, making these ideal cameras for collectors who like colorful cameras.

The Imperial name was so popular for the company, that in 1961, the Herbert George Company would rename itself Imperial Camera Corporation, and would continue releasing inexpensive, all-plastic cameras.

As was common with inexpensive cameras like the Imperial Mark XII Flash, no records were kept about the camera’s production, sales, or even how long the camera was produced. My best guess is probably until about 1962, as some versions of the camera exist with the new Imperial Camera Corporation name.

I cannot be certain when the company ceased to exist, but a good clue comes from a camera released in 1965 called the Imperial Insta-Flash 126, a very simple all plastic camera that used Eastman Kodak’s new Instamatic type 126 cassettes. This camera clearly shows the Imperial logo used on earlier Imperial cameras, but on the box and back of the camera is printed “Manufactured Under Eastman Kodak Patents”. Whether or not this meant the end of Imperial is not clear, but that they were producing cameras under cooperation with Kodak, strongly suggests the end was near.

Today, despite the less than glamorous history of the company who made these cameras, the appeal for mid century simple cameras that were available in an assortment of colors and styles is appealing for those who are fans of “Mid Century Modern” décor. Cameras like the Imperial Mark XII Flash are more likely to be seen as display pieces in someone’s den, or on the wall of an Applebee’s restaurant than in the collection of someone who likes cameras. For those who do collect these cameras for something more than wall decoration, they’re rarely used. But if you’re one of the extremely small number of people who might actually want to use one, they offer a glimpse into a very short, but fascinating window into our past.

My Thoughts

I’m a sucker for a good cheap camera. A huge part of the appeal of collecting and shooting old film cameras is to experience photography how it was done in the past. While I have shot a huge number of excellent high quality SLRs and rangefinders, sometimes their operation is so similar to modern digital cameras, that they lose some of that “old school” appeal that I am looking for.

This is where cheap plastic box cameras with focus free single-element lenses, single speed shutters, and viewfinders who only vaguely suggest what you might be capturing on film, are appealing. These cameras are not ideal for precision photography where framing and exposure are critical. Extreme softness and viginetting is almost guaranteed in your images, you’ll almost likely get a lot more on film than what you see in the viewfinder, and you probably won’t be able to use them in poor light.

But if a quirky looking color plastic walk around camera that is very quick and fast to use is what you’re looking for, then cameras like the Herbert-George Imperial Mark XII Flash are for you. The first time you pick one up, you’ll remark at how light it is. It is a hollow plastic box after all. There is very little that’s not plastic here. The flash reflector, film compartment clip, face plate, and the attachment point for the wrist strap to the body are the only shiny bits you’ll see from the outside. I suppose the shutter probably has some metal in it and of course the film spools (this is a 620 camera after all), but the rest is good ole Polypropylene plastic.

Up top, the Imperial has all the controls you could ever want in a camera, as long as you only want a film advance knob and shutter release. There is no provision for a cable release as the camera has only a single speed and lacks a Bulb or Timed mode. The Imperial came in a variety of colors and this example here is a nice mint green color with darker green accents. Down the center of the top is the viewfinder tube.

On the bottom is a metal clasp for holding the film compartment shut. On the Imperial, the entire body is the film back, with the film compartment permanently attached to the front of the camera. When you release this clip, the entire insides of the body slide out from the green shell. Besides this clip, there is nothing to see, no tripod socket or anything else.

The back of the camera has the exposure counter, aka, the round red window for reading exposure numbers on the film’s backing paper. As the Imperial shoots square 2 ¼ inch images, you get 12 exposures on a single roll. If you have the flashgun attached, the back of the flash is also it’s battery compartment. To open it, simply pry on the edges of the back of the flash to reveal the penlight battery compartment. When I acquired this camera, it still had two Eveready No.915 batteries in there, but they were both pretty corroded.

Each of the two sides are symmetrical with a dark green vinyl wrist strap on the right, and the two push in connections for the flashgun on the left. In terms of cosmetics, the camera has a couple “art deco” style stripes running along the sides, top, and back, converging where the round exposure window is. It looks kind of cool, adding to the “Mid Century Modern” flair that the camera has.

Opening up the camera reveals a very typical box camera style film compartment. If you’ve never opened a box camera before, picture a black plastic cone that starts off small closest to the lens and gets larger towards the back, eventually taking the shape of the film gate. On each side of the cone are posts that hold both the supply spool on the right, and the take up spool on the left. The Imperial is designed to use 620 film and although I tried, 120 spools do not fit. You could probably force them in by trimming them, but I strongly advise against this as it will almost certainly cause you film transport problems, but also, respooling 120 film onto 620 spools is so easy to do.

Up front, other than the metal logo and faceplate, there is nothing to see. This is a focus free camera with a single shutter speed. Unlike other single speed box cameras that sometimes give you an option for Bulb and Instant images or some kind of aperture control via a metal plate with a smaller round hole, the Imperial doesn’t even have that. You get a single speed, fixed focus, and a single exposure. Because of this, you definitely want to make sure before loading film into the camera that you choose a film speed that will work with where you expect to shoot all 12 exposures on the camera. For the modern shooter today, I will stick with a medium speed black and white film that has a lot of latitude. Color slide film probably would be a bad idea.

The viewfinder is a straight through optical tube. There’s a plastic lens on the back and the front, and you look through it to (sorta) compose your image. The image seen through the viewfinder is very small, to approximate what is likely a wide-angle-ish focal length of the lens. Is it 75mm, 70mm, 65mm, or something else? No one knows! Although I was able to see all four edges of the viewfinder while wearing prescription glasses, I had to press my eyeglasses dangerously close to touching the camera. I am sure that those with better vision than I would not have a problem. For as small as the viewfinder was, it worked and was consistent with other inexpensive cameras of it’s era.

And that’s it. The Imperial Mark XII Flash is about as simple as you can get while still being able to call something a camera. It is interesting to note though that although many children’s toy cameras were produced over the past half century or so, I wouldn’t call this a toy as the Imperial is a legitimate camera that is capable of good images in the right situations. The Imperial Mark XII comes from a specific era of photographic history where a simple box camera with no settings of any kind, that you just point at something and press a shutter release was all you needed.

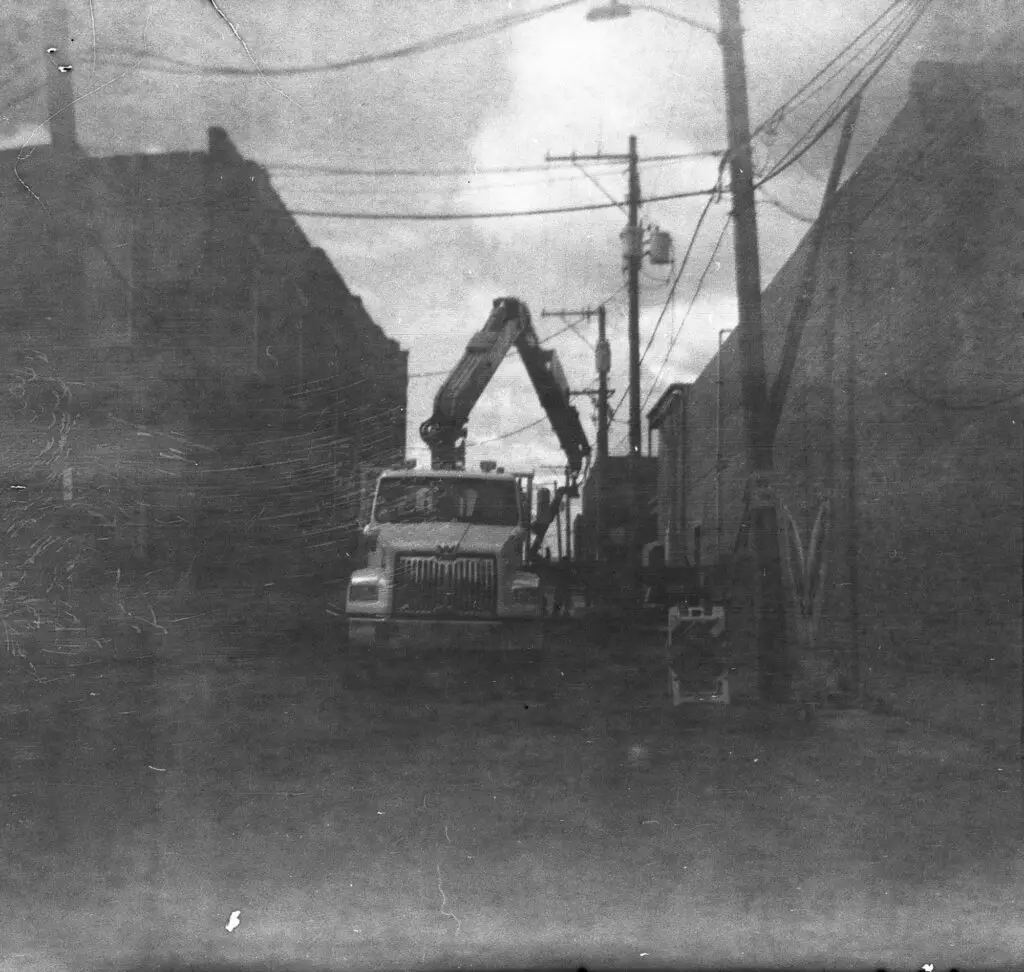

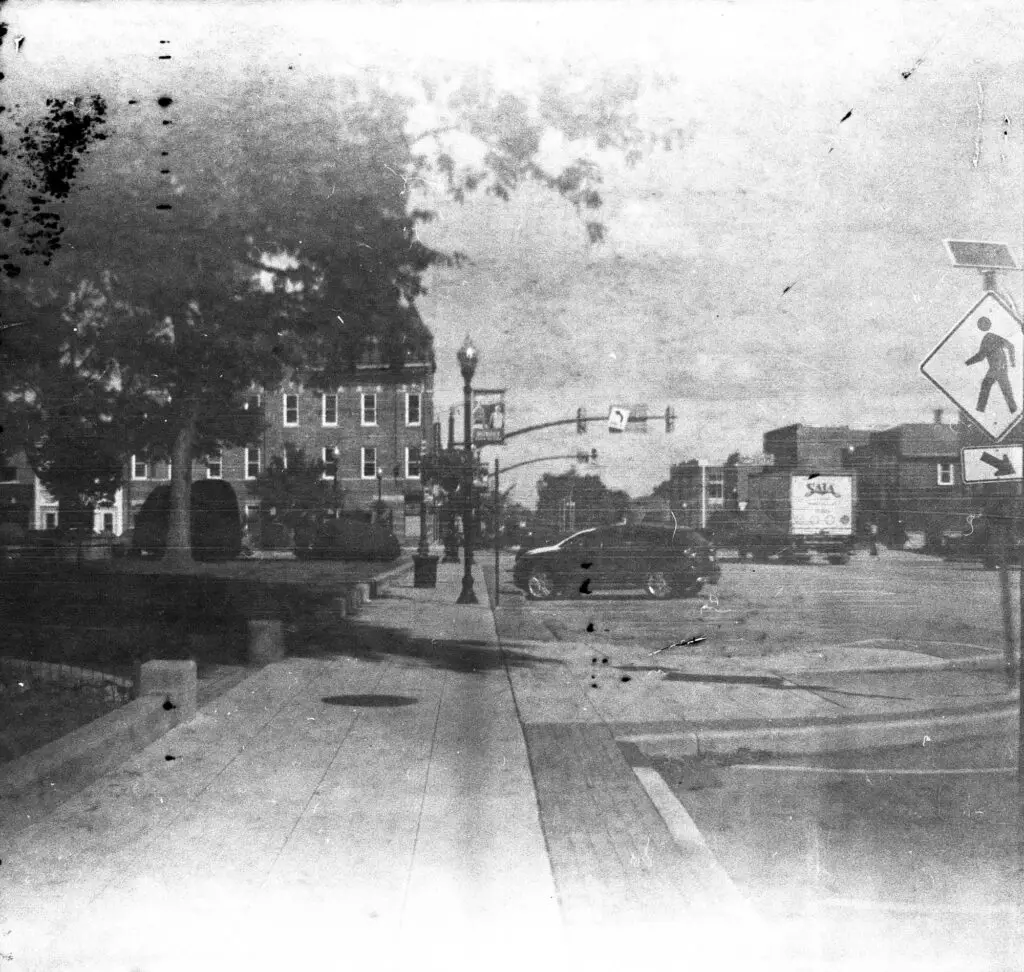

My Results

For my first roll of film through the Imperial, I wanted to try some expired 620 film I have had for a while. Whenever I shoot 127 film cameras, I have a supply of a German film called Supre-Tone which was an ASA 50 speed black and white film from the 1960s that I frequently refer to as time-travel film as I have shot many rolls of this film at box speed with amazing results. Supre-Tone film has never failed me, either because of poor exposure, mold, mottling, or rotted backing paper. In that supply of 127 Supre-Tone, I had a single roll of 620 Supre-Tone that was labeled as a 200 speed film so I thought what the heck?

So clearly, not all Supre-Tone is created equally. Perhaps this roll was stored differently than the 127 I have, or perhaps maybe because it’s a faster 200 speed, it aged much more poorly than the 50 speed stuff. For my second roll, I still went expired, but this time it was some Ilford 100 speed film from the 2000s. I’ve also had good luck with this film in other cameras. Being a 120 film, I had to manually roll that onto 620 spools, but that wasn’t a problem for me.

Part of the appeal, at least for me, when shooting simple cameras like the Imperial, is that you never know what you’re going to get. Although it is true that you can have surprises with any camera, at least with a rangefinder or SLR camera, you have a general idea of what your composition is going to be before pressing the shutter release, the lenses are usually good enough to be able to expect quality images, and with a wider range of exposure settings, you can reasonably expect to make good images in most light.

With a camera like the Imperial Mark XII Flash, there is no control over exposure, the viewfinder is so small and imprecise that it only gives you an approximation of what you’re going to capture, and there’s no telling what kind of optical anomalies the single element meniscus lens will give you.

What’s nice though is that more times than not, the results from these simple plastic fantastic box cameras are usually better than you’d expect. Looking at the images I got from both rolls of film I shot in this camera, center sharpness is pretty good. The great thing about meniscus lenses is that they’re so simple, the light that hits the center of the lens passes mostly unobstructed to the film plane, delivering excellent sharpness.

Near the sides and edges are where things usually fall off a cliff. Curved film planes help to maintain a consistent distance the light has to travel from the center to the edges improving sharpness, but it definitely does suffer.

Looking up close at the images I got, there is a lot of softness off center, especially in the top half of the images. I actually think that in this case, the meniscus lens isn’t entirely to blame, rather the lack of a consistently flat film plane is. The Imperial lacks a film pressure plate. As film transports through the camera, it simply glides over the plastic edges of the film gate, held in position only by the imprecise inside of the rear door. Any amount of variance of the film wiggling around in the film compartment, even by a millimeter, will have a dramatic effect on focus. I once shot a 35mm camera in which the pressure plate had fallen off, and the entire roll was completely out of focus.

Beyond the softness near the edges, other anomalies like vignetting near the corners are evident as well. Vignetting should be expected in any box camera, especially outdoors, but that’s not a bad thing as I think it gives a vintage character to these images which add to it’s appeal. If leveraged properly, portraits can be very effective with these types of cameras as you can get your subject sharply in focus in the center, with a soft and darkened border around it.

As for using the camera, well, there’s not much to say. The camera has almost no controls. Simply advance the film until you see the next number in the red window and press the shutter release. There’s no shutter speeds, aperture settings, or focus control, just point and shoot. I’ll even go a step farther and suggest the viewfinder is optional as it does such a poor job of properly reflecting what will be captured on film, you could just point this camera into the vague direction of what you want to capture and press the shutter release.

About the only thought you need to put into this camera is what film to use in it. Black and white films with a lot of latitude in the range of ASA 50 to 100 would be ideal. If you were going to shoot in very low light, you could go with a faster film, but be careful as the red window on the back does not have a door and putting too fast of a film in the camera could cause light to leak in through the back. If you wanted to shoot color, you could, but options for slow color film is limited these days, and I definitely would not recommend slide film in this.

Overall, the Imperial is a cool camera to have. I assume that a huge number of these cameras that are out there today are used primarily for decoration, which to be honest, is how mine will be too. I don’t see myself coming back to this camera often, it at all. It looks great on a shelf, but if you do have one, I would encourage you to try it at least once. If there’s one really positive thing I can say about them, is that the Imperial Mark XII Flash is so simple of a camera, there’s almost nothing to go wrong with them, so that display piece you have on your shelf, almost certainly works fine! Go and shoot it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Imperial_Mark_XII_Flash

https://medium.com/@Adam.Welch.Photographist/plastic-sex-the-imperial-xii-flash-ccf54d142697

https://utahfilmphotography.com/2016/11/02/the-official-girl-scouts-of-america-camera/

http://moominsean.blogspot.com/2007/08/imperial-mark-xii-flash.html

https://digitofilm.blogspot.com/2017/07/imperial-mark-xii-flash-review.html

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=398

https://www.flickr.com/groups/35034354696@N01/discuss/72157594349188970/

Gonna think of “drugs with a reputation” every time I pass a Walgreens now.

Mike, do you have a copy of “Brass, Glass and Chrome” by Carlton Lahue? It’s a good source of information on the Chicago and NYC camera business mid-20th century.

So far I’ve avoided the rollfilm Imperials. They just seem too crude. Yet you got reasonable results from this one.