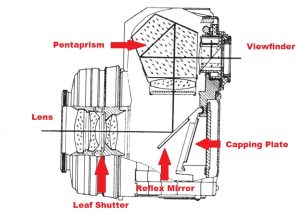

This week’s Keppler’s Vault is a “two-fer” offering two separate articles about the 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera, one from August 1957 and the other from February 1960. In the first article, Herbert Keppler and Arthur Kramer take a look at the state of Prism Reflexes and in the second, Bennett Sherman goes into technical detail of how SLRs work, covering a wide range of topics, such as why some viewfinders are brighter than others, and how different shutter systems work.

It might be hard today to imagine a world where there might have been skepticism about the Single Lens Reflex camera, as the SLR has been the dominant format of camera for well over half a century. Everyone from casual family snapshooters to the pros have likely used some type of film or digital SLR camera at some point in their lives.

The 1950s was a decade of change in the photography industry, not only because of the rise of Japanese camera makers, but also a shift from rangefinders to SLRs. It didn’t happen overnight though. The earliest SLRs had many significant disadvantages that were seen as deal breakers to photographers at the time.

The first was that most early SLRs did not have “instant return mirrors”. This is a feature much like turn signals, windshield wipers, or electric starters on automobiles don’t even seen like features today. You mean to tell me that early cars did not have these features? Yep. When you would use an early SLR, upon firing the shutter the mirror would remain in the “up” position, blocking the viewfinder until you advanced the film and cocked the shutter again. Rangefinders didn’t have this problem as you could always see through the viewfinder no matter the state of the shutter.

The automatic diaphragm was also an innovation that didn’t come until a few years after the earliest SLRs. An automatic diaphragm is one in which the lens iris (the aperture) is always wide open (the smallest f/stop number) allowing for maximum light to enter the viewfinder when composing your image. You could select a smaller f/stop on the lens and the iris would remain wide open, and only stop down at the moment right before the shutter would fire.

This was an advancement that was accomplished one of two ways. For the Ihagee Exakta, Miranda, and some other cameras with front shutter releases, the lens would have an external shutter release that would slip over the camera body’s main shutter release and when you’d press it, it would simultaneously stop down the lens and fire the shutter at the same time. Other companies had internal linkages much like the M42 lens mount which used a small pin inside of the lens mount that when pressed by a lever inside of the mirror box, would stop down the lens.

Early SLRs also had simpler viewing screens without modern conveniences like a Fresnel screen to increase brightness, or focus aides like a split image or microprism collar. The earliest SLRs had dim viewing screens that when used with slow lenses or those lacking an automatic diaphragm meant that your view through the screen was quite dim.

Even for the later cameras that had all of these features, some rangefinder shooters still had a hard time adjusting to the larger size of the SLR with it’s larger mirror box and pentaprism hump on the top of the camera. These photographers didn’t like the delay from the mirror needing to swing out of the way before the shutter could open. The momentary “blackout” of the viewfinder meant that the photographer couldn’t see through the viewfinder at the exact moment a photograph was captured. The sounds of the moving mirror were also considered an obstacle to discreet photography as SLRs were generally a lot louder than their rangefinder counterparts.

These two articles cover some of the early methods in which manufacturers attempted to overcome some of these challenges. The Alpa reflex had a combined SLR and rangefinder within the same viewfinder. Zeiss made the Contaflex with a bright Fresnel screen that was brighter than any other, but had the drawback of only being able to focus in the center of the screen.

There are some interesting predictions, especially in the first article where an unnamed “optical expert” predicted that the leaf shutter SLR like the Contaflex and Retina Reflex would supersede the focal plane shutter, calling it a has-been. The article talks about the challenges of wide angle lenses and how the retro focus design was born, and how some makers approached the challenge of “mirror shake” at slow shutter speeds when the moving mirror caused the camera to move and blur images.

The second article is much more technical in nature, but attempts to answer many questions that I have often wondered myself.

- Why are Fresnel screens brighter?

- Why do some split image focus aides black out when using small apertures?

- Why do telephoto lenses cause darkness near the edges?

- Why did so many manufacturers produce 58mm lenses for SLRs?

It goes over some of the benefits and challenges of a leaf shutter vs a focal plane shutter, it talks more about wide angle lenses and why they usually had very large front lens elements, and why early SLRs would cut off some of the exposed image in the viewfinder.

Finally, in the last few paragraphs, the article predicts future advancements of SLRs such a greater variety in lens mounts, built-in and coupled exposure meters, faster lenses, and smaller bodies. Each of these things were just around the corner when this article was written in 1960.

Whether you care about the historical element of the articles, there is some really great technical explanations about early SLRs and why they were designed the way they were. Even if you don’t care about the tech stuff, there is some cool images of old cameras like the Alpa Reflex and Rectaflex that we don’t often see today.

The second article:

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2018.