The earliest days of any new technology are always fascinating to me. Not just for the stories, but for the process of how things like photography made the journey from a vision to reality. Rarely is it as simple as some inventor one day waking up from a dream and saying, “Today, I will invent the camera!”

The reality of innovation is that things happen slowly, and often develop over time through multiple small steps. Many times, one person cannot claim sole claim as the inventor of something as often more than one person worked on a similar technology at the same time, and perhaps some credit is owed to both. Just like like Edison and Tesla, photography cannot be credited to just one single person.

If you spend no more than five minutes looking up the history of photography, you will no doubt read about Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, a French artist and inventor who invented the daguerreotype which is considered to be the first successful process of making what we would call today, a photograph.

The idea of capturing light onto a light sensitive emulsion that results in a permanent photograph did not start with Daguerre, as an earlier invention called the heliograph was invented by Daguerre’s partner, Nicéphore Niépce in 1826. Niépce’s 1827 heliograph, View from the Window at Le Gras is the oldest surviving photographic image in the world.

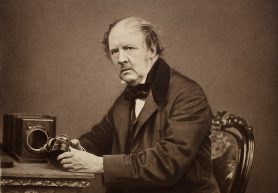

But this article is not about either Daguerre or Niépce. Although both men rightfully deserve recognition for their contributions in the earliest days of photography, many of what makes photography recognizable today were thought up by an Englishman named William Henry Fox Talbot, a man not credited with being the first, but one that helped advance it with new ideas and concepts.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings to you two articles from back to back issues in December 1952 and January 1953, telling the story of Henry Fox Talbot, Esq. This short biography was likely the first comprehensive publication of this part of photographic history in any modern magazine.

For a brief intro, although Talbot is often considered to be a competitor to Daguerre, he didn’t start out this way, in fact, the two men both started on their photographic journeys without any knowledge of the other.

Talbot was an accomplished scientist, a respected member of England’s Royal Society, and at one point served as an elected member of Parliament. Many of his works were published in several respected scientific journals of the time, and he mingled with many of the era’s top minds.

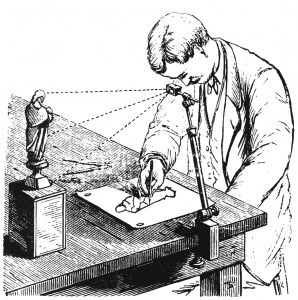

In the early 1830’s Talbot’s career and social life took him and his wife on many travels, which he wanted to document by way of drawings. Talbot wasn’t a very good artist, so he tried a couple types of technology including the camera obscura and something called a camera lucida, a simple device that is like a modern day beamsplitter attached to an articulating arm.

The user positions the camera lucida above his paper, and points it at the subject he wishes to draw. The semi-reflective prism allows the user to both see through the prism onto paper below, while also seeing a reflected image of what he wishes to draw. By seeing both his image and the paper at the same time, the user can then draw what he sees without having to move his eye.

Unhappy with his results from both the camera lucida and various other contraptions, Talbot wondered if there was a way in which instead of having to draw am image seen through a device, if there was a way to make a type of paper that could capture the light and make an image, doing the work for him.

Unaware of any previous or current attempts at what would eventually become photography (the term was not yet used), in January 1834, Talbot started work on various combinations of silver and salts brushed onto paper in an effort to darken and lighten parts of the paper depending on what amount of light hit it.

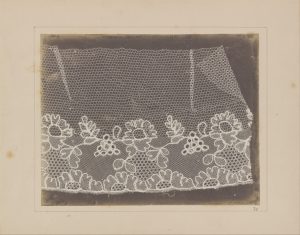

Henry Fox Talbot’s first experiments were done simply by placing household objects into the treated paper to make silhouettes. His initial successes proved he was on the right track, but the paper was not sensitive enough to light to imprint upon images from a camera obscura, so he continued working out ways to make the paper more sensitive.

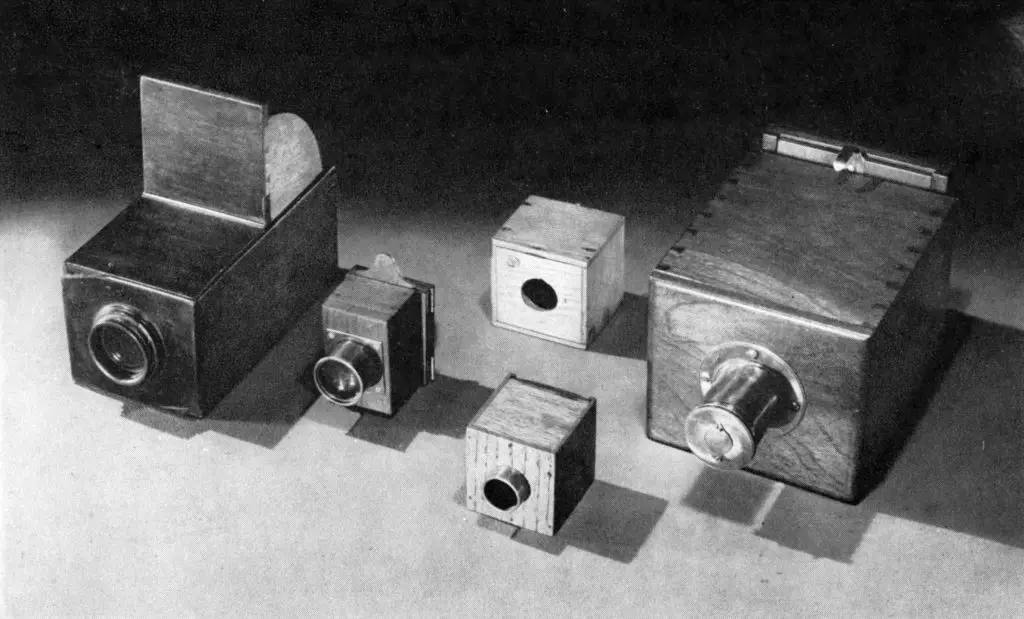

As time went on, Talbot discovered he could directly imprint images from a large aperture lens in a small wooden box onto his light sensitive paper. Since the only large aperture lenses available at the time had very short focal lengths, the boxes had to be small. Talbot’s wife, upon seeing his tiny cameras, gave them the nickname “mousetrap cameras”, a name that would eventually be used to refer to many of Talbot’s and other early cameras.

By late 1835, happy with his early successes, Talbot lost interest in this endeavor and started work on a variety of other projects, most of which involved light, and other types of microscopy.

Unbeknownst to him, over the next three years, Louis Daguerre continued work on his own photographic process, perfecting many of the same steps as Talbot. In January 1839, word through the scientific community reached Talbot that Daguerre was about to publicly announce a process he had come up with involving light sensitive paper that not only could capture an image through a lens, but would make the image permanent so that it could be re-exposed to light without damaging the image.

Talbot realized Daguerre’s work so closely resembled his, that once word got out to the larger community, that receiving any credit for his own work would be hard to obtain. He quickly got to work, rounding up some examples of his work, and writing his ideas down on paper, not only of how his images were made, but how negative images could be copied into positive images. He attempted to use his influence in the Royal Academy to put priority on his work over Daguerre’s and thus began a month’s long back and forth between he and various other members of the community who had already seen Daguerre’s work, attempting to establish his findings first.

In addition to how he created negative and positive images, Talbot also wrote about how copies and enlargements could be made, how half-tones could be used to print gray instead of black ink, and eventually, the ideas which would lead to use the use of electronic flashes.

Without repeating too much more of what’s in the article below, 1839 was an exciting year in the history of photography. The debut of Daguerre’s process of imprinting images directly onto plates, and Talbot’s onto photographic paper which is then copied into a positive image to be displayed directly on paper gave the world two options for this exciting new technology.

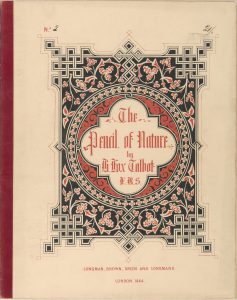

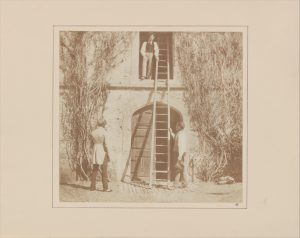

From 1844 to 1846, Henry Fox Talbot published a book in six parts called The Pencil of Nature that is regarded as the first ever published collection of photographic prints, each one pasted in by hand. Inside were a total of 24 of Talbot’s prints showing the evolution of his process. Photography was still unfamiliar to most people then, so being able to see these images with all of their detail, not done by pencil, but rather nature, was likely an amazing sight.

Over the next decade, both men, along with many others continued to improve their processes. Improvements in the sensitivity of his paper meant that physically larger lenses could be used to make larger prints. Lens technology improved with Charles Chevalier‘s achromatic lenses and Joseph Petzval‘s portrait lenses.

By the end of the century, other advancements in glass plate processes, celluloid film, faster lenses and shutters would lead to the modern day camera, which in the 20th century would see revolutionary designs in cameras, film, and eventually digital photography.

It’s hard to say with certainty that without men like Henry Fox Talbot or Louis Daguerre, whether we’d have photography today, as it’s likely someone else would have eventually come along and created the same thing, but with articles like these, we get a glimpse back into a time to learn about the people who actually did it. With resources today like the Internet, you can just look up Talbot on Wikipedia and read about his contributions, but for me, I prefer articles like these, telling the stories in a printed magazine from 1953, which have now become a part of history themselves.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.

Then: Talbot vs Daguerre. More recently: Gates vs Jobs & Wozniak. Thanks for an interesting post, Mike.