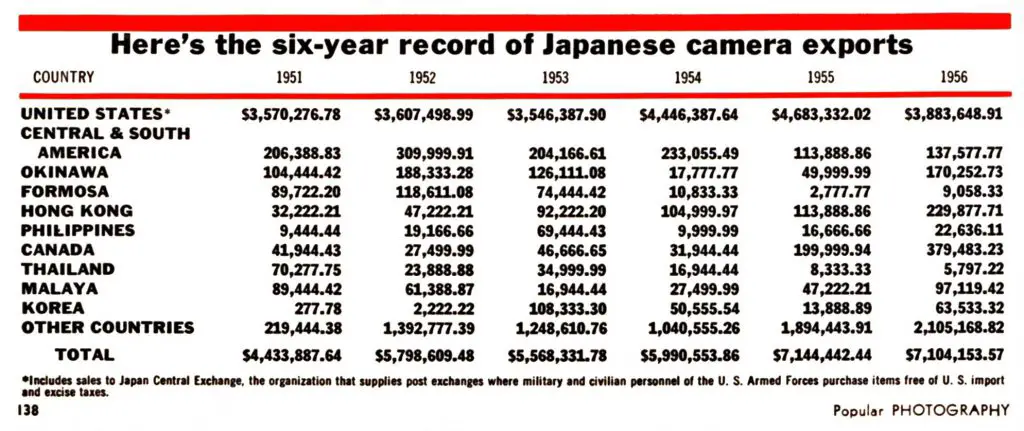

Between the years 1947 and 1955, the total amount of exported camera goods from Japan to the rest of the world rose from a miniscule $9200 to $7,144,442.44, $4,683,332.02 of which went to just the United States. In the decades that would follow, Japan would become the world’s biggest and most widely respected maker of cameras and lenses. Companies from all over the world, including the United States, Germany, and even the Soviet Union used Japanese companies to help design, build, or sell products in some capacity.

I’ve covered the history of Japan’s rise to the top of the industry on this site numerous times. Most of the stories involve David Douglas Duncan and other LIFE Magazine photographers, but there were also distributors like Joseph Ehrenreich and C.R. Skinner, and authors like Herbert Keppler of Modern Photography and Jacob Deschin of the New York Times who did their part to spread the word about the excellence of cameras and lenses coming from the small island country.

Despite all of this information and evidence to support the clear advances in both quality and technology of Japanese products, by the late 1950s, there were still some skeptics. A certain percentage of the population was not ready to trust products from a country who barely a decade before, was the enemy of the American people (of course that didn’t stop them from buying German products).

Back in 2018, I published a three part series on the state of the Japanese Photo Industry from the April 1957 issue of Popular Photography which aimed to share with the American public the advances that Japanese companies were taking to not only build better products, but through independent organizations such as the JCII and JCIS to hold the entire industry to a higher standard. That 48 page Special Section was chock full of articles explaining where the industry was and where they were headed, and advertisements from Japan’s top companies showing off their latest and greatest.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings you a similar article, this time from the May 1959 issue of Modern Photography, covering the latest products and innovations from the best of the Japanese photo industry.

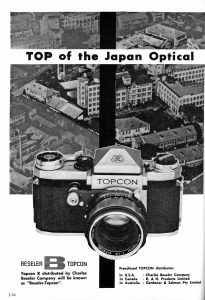

As was the case with the 1957 article, there are ads for companies like Riken (Ricoh), Asahi Optical (Pentax), Canon, Olympus, Yashica, Beseler Topcon, Minolta, Fuji, Sekonic, Aires/Kalimar, Copal, Petri, Seikosha, Mamiya, Arco, Beauty, Walz, Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), and Konica. If you like looking at old ads for classic cameras, then this article is full of them!

Beyond the ads, there’s some articles, starting off with introductory messages from Tatsunosuke Takasaki, Minister of International Trade and Industry, and Dr. Masao Nagaoka, President of the Japan Camera Industry Association who both proclaim the 1959 Master Photodealers and Finishers Association Convention in Philadelphia to be a tremendous opportunity for the Japanese Photo Industry to show off their progress to the whole world.

Nagaoka runs down several of the benefits of Japanese products, such as technically superior optics, cameras with fast 1/1000 shutters, and those with incredible value. It is clear that Japanese cameras and lenses of this era were at the peak of their abilities, and although there still might be a few doubters out there, it would have been extremely difficult to deny the quality of the products being shown at that year’s show.

A great deal of effort is shown how professional photographers from newspapers, magazines, and other commercial industries rely on Japanese cameras. Gone were the days where field photographers ran around exclusively with Leicas and Rolleiflexes, now Nikons and Canons have been taking their place.

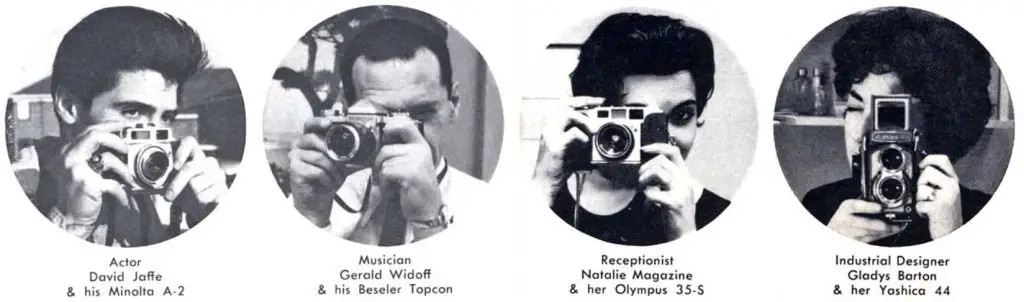

Perhaps the reader of this article wasn’t impressed with what the pros were shooting, and wanted to see what the average pop star or regular person used, so images of musician Gerald Widoff with his Beseler Topcon, Actor David Jaffe with his Minolta A2, and “Receptionist” Natalie Magazine and her Olympus 35S are name dropped with images of each.

You can’t talk about the quality of Japanese cameras and lenses, without talking about the Japan Camera Inspection Institute, so quite a bit of time is spent on what this organization did. In the early postwar years, there were a huge number of cheaply built and low quality cameras coming out of the country. Toy cameras like the Hit, and cheap knock off models by companies like Shinano Pigeon, Neoca, and other lower end companies made cheap and basic cameras, that weren’t doing the international perception of Japan as a viable maker of quality goods, any favors. A huge number of knock off Rolleicords and scale focus cameras likely confused western photographers into thinking this was the best the Japanese people could do, so the JCII was formed to create a quality assurance seal that not only guaranteed absolute quality, but also that Japanese products were unique and not simply rip offs of other company’s products.

The gold foil JCII stickers were commonly found on top tier Japanese cameras, lenses, and other photo equipment well into the 1980s, ensuring the end user that cameras were checked for proper operation and that you were buying a fully guaranteed product.

The whole 48 page article (some are double pages) reads a lot like a promotional pamphlet, which in a sense, it is. The idea that an entire industry would come together to promote itself as a whole is something you don’t see anymore. I doubt there ever has been a time when General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler ever had to come together and promote the entire American automobiles and the quality assurance standards that all American products are subjected to.

It is clear that in the years after World War II, Japan had a lot to prove, and as we look back in time, they definitely succeeded. The Japanese photo industry opened the door to other Japanese industries. Companies like Honda, Toyota, Sony, Mitsubishi, Yamaha, Nintendo, and Panasonic rode a way of success and trust first established by Nippon Kogaku, Canon, Minolta, Seikosha, and many others. Although I won’t go as far as to say we wouldn’t have those other Japanese companies without them, my guess is, the time lines would have looked much different had they not existed.

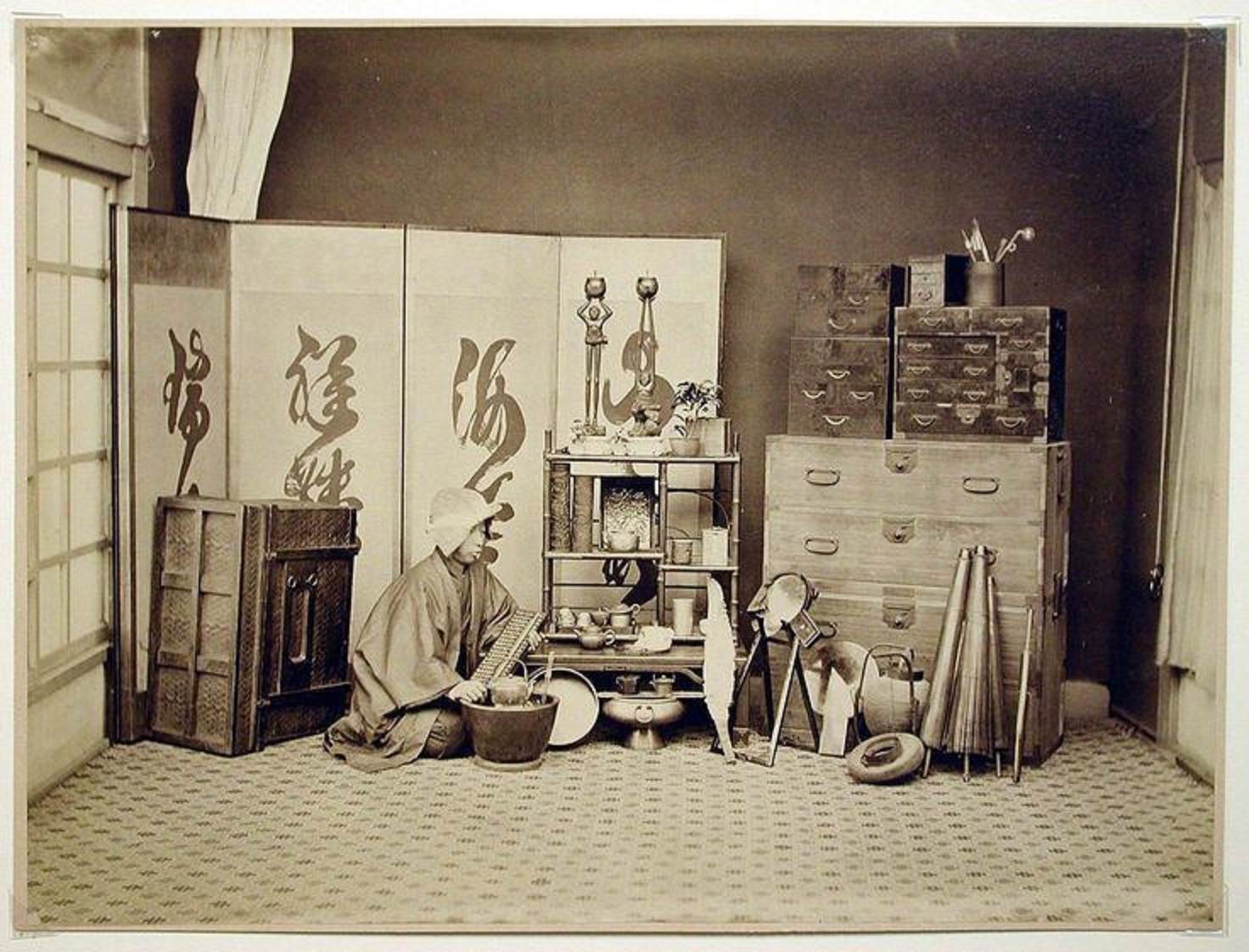

This next article is from May 1976 and is about Japan’s earliest photographers. For most of the world, Japan and photography didn’t go together until after the war. For those with a better understanding of history, you likely knew of prewar cameras like the Hansa Canon, Minolta press camera, or even the Konishiroku Cherry camera, but it might surprise you that Japan’s history with photography is almost as old as every other country’s.

Photographers such as Ueno Hikoma from Nagasaki were pioneers in the Japanese photo industry. Working with glass plates using early imported and Japanese built cameras, Hikoma was known for his portrait work. He photographed emperors, visiting dignitaries, and landscapes, giving glimpses into life in Japan at the time, rarely seen elsewhere.

Hikoma wasn’t the only Japanese photographer as Iwata Nakayama, Shizo Fukuhara, and Ihei Kimura helped inspire later photographers and the men and women who helped build them.

Would it not be for these early pioneers, perhaps there might not have been anyone to start the companies that would eventually make up the the Japanese photo industry after the war. That’s a bit of a stretch I know, but at the very least, this short article gives a glimpse into a little part of the country’s history, not often found elsewhere.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.

Test Comment