This is a Kodak Pony 135 Model C, a 35mm point and shoot camera made by Eastman Kodak in Rochester, NY between the years 1955 and 1958. This was the last in the original series of Pony models dating back to the original Pony 828 from 1949. The Model C upgrades the lens to a faster f/3.5 Kodak Anaston, a Kodak Flash 300 shutter with faster top 1/300 speed, and improved flash synchronization. The Pony was Kodak’s entry level 35mm series in the 1950s, offering good, but not great plastic cameras for an affordable price.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 44mm f/3.5 Kodak Anaston Lumenized 3-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 2.6 feet/meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Kodak Flash 300 Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: M and FP X Flash Sync

Weight: 443 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_pony_135.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kodak Pony was one in a long line of inexpensive, but effective cameras produced by Eastman Kodak in the mid 20th century for the sole purpose of creating new customers for Kodak film. Despite having simple triplet lenses and four speed shutters, Kodak Pony cameras make surprisingly good images. Optimized for Kodak’s black and white and color film stocks of the era, including Kodachrome, these are still very usable cameras today. This Model C is the most desirable model with an upgraded top 1/300 shutter speed, and a slightly wider and faster 44mm f/3.5 Anaston lens that is not only more effective in lower light, but also has a larger depth of field, meaning that scale focusing is easier than previous models. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.7 | ||||||

History

The Eastman Kodak Corporation dominated the world of film photography for over a hundred years, from the first Eastman Dry Plates that George Eastman produced in his kitchen, to the original Kodak from 1888, the first $1 Brownie from 1900, to the introduction of Kodak’s daylight loading 35mm cassette and the introduction of the Retina series in 1934 to the release of Kodachrome in 1935, Kodak was at or near the top of the market in every category.

Throughout their entire existence, Kodak was a film first company. Although Kodak had built and sold many different cameras, every time they released a model, it was for the intent of selling more film. The more people who bought Kodak cameras, the more people there would be to buy their film. This philosophy was not unique to Kodak as other 20th century film makers like AGFA, Fuji, and even Ilford took a similar approach.

In the early 20th century, Germany dominated the camera industry with a huge number of models coming out of nearly every city, Dresden, Stuttgart, Hamburg, Wetzlar, and many others produced huge numbers of cameras ranging from simple boxes, to the most expensive top of the line cameras in the world.

After World War II however, exports from Germany came to a halt. In addition to heavy damages to factories all across the country, political changes in what would become East Germany, and the complete disorder of the German economy meant that anyone looking to buy a camera at that time needed to look elsewhere.

To fill the void, established American companies like ANSCO, Argus, Ciro, and Candid, took the charge and started releasing new models at breakneck speed. Eastman Kodak’s new Daylight Loading 35mm cassette which had slowly been gaining popularity before the war, was the dominant format for 35mm film after. Kodak’s new Kodachrome color film was very popular and was a hot item for professional and amateur photographers alike.

To help meet this demand, Kodak released a huge number of medium format and 35mm cameras. At the top end of the spectrum were expensive cameras like the Kodak Medalist and Kodak Ektra. A little less expensive were the Kodak Retina series which although produced in Germany by Kodak AG, resumed production around 1946. On the low end of the spectrum were Kodak’s Bantam series, which used a version of 35mm wide roll film called 828. The 828 film format debuted around the same time as Kodaks daylight loading 35mm film, but was considerably less expensive and was used in (mostly) cheaper cameras.

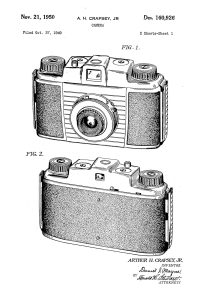

To meet the increasing needs for a consumer friendly and inexpensive camera that could still produce good images, Kodak turned to their in house designer, Arthur H. Crapsey to come up with something new. Crapsey would later go on to design a huge number of other successful Kodak cameras throughout the 1950s such as the Brownie Hawkeye, Brownie Bulls-Eye, Bantam RF, Automatic/Motormatic 35, and the entire Signet series.

In 1949, Crapsey’s new camera, the Kodak Pony 828 was revealed. Using an all new and mostly plastic body with a 3-element Kodak lens with their patented Lumenized color coating and a simple 4-speed shutter, the Kodak Pony was Kodak’s least expensive miniature camera, and was ideal for the beginning photographer who wanted to take high quality color and black and white images, without a huge investment. With a price of only $29.95 including tax, which was one-fifth the price of a Kodak II rangefinder, the Pony 828 was a heck of a bargain.

A year later, Kodak would release a 35mm version of the camera, called the Kodak Pony 135. This new model had all the accommodations to use 35mm film, with a new exposure counter and rewind mechanism, but otherwise remained the same for only $5 more. At a price of $34.95 in 1950, which when adjusting for inflation, compares to about $420 today, the Kodak Pony was reasonably affordable to most Americans.

By 1953, Kodak had expanded their 35mm camera line into three distinct tiers, the Kodak Retina series at the top offered state of the art lenses, shutters, rangefinders, and German build quality, in the middle was the Kodak Signet series which still offered rangefinder focusing with Kodak’s “good but not German-good” Ektar and Anastar lenses, and then the Pony at the economical end of the scale.

Kodachrome and Ektachrome slides would explode in popularity in 1950s America with sales of slide film and slide projectors and screens become the go to way of sharing your favorite vacation and holiday photos with friends and family. Kodak proved that you didn’t need a high spec rangefinder or reflex camera to make good slides.

Kodak’s philosophy with all their cameras is that they were good enough. The Pony was good enough so that the vast majority of family snapshooters wouldn’t complain about the quality of images they got. If you wanted something better, you would just move up into the Signet or Retina lines.

This appeared to work as both the Pony and Signet series would expand with more models at different price points. The original Pony 828 would soon be discontinued as the economy of 8 shots vs 20 or 36 exposures for the Pony 135 won people over.

The original Pony would receive incremental updates to it’s shutter and lens with the Kodak Pony 135 Model C being released in 1955 which upgraded the shutter to the Flash 300 with top 1/300 shutter speed, a faster f/3.5 44mm Anaston lens whose wider focal length allowed for wider depth of field, making focusing easier, and a new rigid mount which meant the lens no longer had to be extended before each photo was taken.

This new and upgraded Pony offered all these upgrades while still selling for nearly the same price of $33.75 as the original Pony 135. With an inflation adjusted price of $360 however, the new model was actually more affordable than the model.

The Pony sold well and to keep up with consumer demand, in 1957, two new models, called the Pony II and IV were released at the same time (no word on a Pony III) each representing a basic and advanced model. Both cameras received a design refresh once again by Arthur Crapsey, but the Pony II offered a single shutter speed and a 4-element Anastar 44mm f/3.9 lens and flash sync. The Pony IV also had a 4-element Anastar lens, but was a bit faster at f/3.5, and also came with a 4-speed shutter with speeds from 1/30 to 1/250 offering a similar level of flexibility to the original Pony models.

Kodak would eventually discontinue the last of the Pony models in 1962 after a respectable 13 year production run, making the series one of Kodak’s best selling American built 35mm cameras. While I have not found any production numbers of the line, I have to imagine that if you were to come across any color slides taken during this era, there is a very good chance that some were shot with a Pony camera.

Today, there’s not a big market for lower end cameras like the Kodak Pony. These are cheap and easy to find cameras that do not demand much value on the collector’s market, but to dismiss them altogether is a mistake. If there was one thing Kodak was good at was making cameras that were good enough. Kodak Pony cameras are so simple, there’s little to go wrong with them. Assuming a camera was taken care of and not abused, if you come across one today, there is a very good chance it still works. Kodak also had a knack for producing really nice 3 and 4 element lenses, meaning that images shot with one of these cameras is likely going to look better than you might expect.

If you were to come across a Kodak Pony of any type, whether it’s the original model 828, the Model C, or the last of the Pony IVs, you owe it to yourself to give it a shot. Just don’t pay too much for it as you’ll likely find another pretty easily.

My Thoughts

The release of this review for the Kodak Pony could represent the longest amount of time in between when I first intended to review a camera and when I actually did. I picked up my first Pony 828 back in the summer of 2016 when I first started reviewing cameras. A Pony 135 came shortly after that and in early 2017 I took some beauty photos of those cameras to use for an upcoming review.

Except, that review never happened. For reasons I can’t always explain, the review languished as a draft and eventually was deleted as I overhauled the site back in 2018. I lost interest in the Pony and figured I’d come back to it someday.

That day happened in late 2021 when friend and fellow blogger, Alyssa Chiarello had mentioned to me she had a Kodak Pony 135 Model B that was given to her by her uncle that had tried to fix herself. She was able to get the camera apart and clean the shutter to get it working again, but couldn’t get it back together. Asking if I would be willing to fix it for her, I agreed and off it went to the post office.

To Alyssa’s credit, for such a simple camera, the Pony is kind of a pain to get back together, because once you remove those two screws around the front beauty ring, you also disconnect a metal plate that acts as both the infinity and minimum focus stops. With that plate out of position, it is impossible to set the front lens group to the proper position for accurate focus.

After several failed attempts, I got it together and wanting to make sure the camera was ready to go before sending it back, I shot a quick test roll of pics. After developing that roll and being really impressed with the results, I became interested again in revisiting the Pony.

The Kodak Pony comes from an era in which Kodak’s design department was at the top of their game. Model after model of attractive cameras like the Signet series, the Kodak Chevron and Pony were all designed by Arthur H. Crapsey, Joseph Mihayli, and Walter Dorwin Teague.

The Pony was Kodak’s entry level camera, but despite it’s point and shoot intents, it was a solidly built camera with an attractive symmetrical design. Made out of equal parts of metal and plastic, the Kodak Pony Model C weighs in at 443 grams which is substantially heavier than plastic point and shoot cameras that were soon to come in the next decade. The Model C is the only in the Pony series to have a main body with a dark brown color. All other Ponys from the original 828 to the Model B are black.

Up top the camera has two metal knobs on each side, one for rewinding on the left and film advance on the right. The lack of a film advance lever is not at all missed here, as advancing the film on the Pony is quick and easy to do with a quick twist of the wrist. Dead in the center is the viewfinder which starts out narrow in the back and gets wider towards the top. In the center of the viewfinder hump is Kodak’s gorgeous red circular Kodak logo. In the history of camera brands with red round logos, most people today would think of Leica, but Kodak did it first, and frankly, I wish they had never stopped. Flanking the viewfinder are two dials, one on the left which is a film reminder dial, and on the right the is the subtractive exposure counter. After loading in each new roll of film, the counter must be manually set to whatever number of exposures remain on the roll. Finally, above the exposure counter is the chrome shutter release button, which is the only feature on the camera’s top plate that breaks up it’s symmetry.

On the bottom, the Pony retains it’s symmetrical shape, although with far less to see. Centrally located is the metal 1/4″ tripod socket and a plate for the camera’s serial number. Although the Pony was marketed at the beginning photograph who likely wouldn’t need a tripod very often, the central location and metal construction are certainly nice touches, further suggesting that just because the Pony was inexpensive, doesn’t mean it’s cheap.

Around back, we see the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder. Although small, it’s quite a bit larger than the rice-sized peep holes on earlier 35mm cameras like the original Kodak Retina, allowing you to see the entire viewfinder image even while wearing prescription glasses. To the right of the viewfinder are two small levers, both indicated by engravings in the top rim of the film door.

The first is what the Pony’s manual calls a “Film Release Lever” which overrides a lock preventing you from over-winding the film. Swinging out this lever and allowing it to return to it’s original position is required when advancing the film. This needs to be done both when loading in a new roll of film, but also while shooting the camera as the Pony does not override this when advancing the film. To it’s right is a smaller button that when pressed, deactivates the film transport, allowing you to rewind film at the end of a roll. The rest of the back of the camera is just the textured brown plastic that covers most of the body.

The camera’s right side has a metal clasp with a small button in the center which when pushed in, allows you to slide the clasp down, releasing the latch for the removable film back. Symmetry continues on both sides of the camera with a similar, although non-movable clasp on the camera’s left side. Both sides have a strap loop on top allowing you to connect the fabric neck strap included with the camera. Most Kodak Ponys I’ve seen still have this strap connected.

With the camera back off, we see the film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a double slotted and fixed take up spool. I found it to be slightly easier to load film by inserting the film leader into one of the two slots before inserting the cassette into the chamber on the left. Doing it this way prevents the film from spinning the sprocket, which keeps engaging the double exposure prevention. Once you’re sure the film is securely attached to the take up spool, insert the cassette into the camera, and reattach the door. You’ll still need to advance the film again to get past the exposed section of the film, however.

Looking down upon the Kodak Flash 300 shutter, there is a lever that controls the lens diaphragm, offering f/stops of 3.5 through 22. Behind this lever are two scales giving suggestions on lighting for Kodachrome and Ektachrome film. Around the perimeter of the front of the shutter is a ring for controlling shutter speeds. Four selections from 1/25 to 1/300 are offered plus Bulb. Although the ring is rotated around the shutter, a triangular tab points to marked shutter speeds on top of the shutter. All speeds are indicated in black except 1/50 which is in red, matching the previously mentioned exposure recommendations for Kodachrome film.

Turning the camera to face you, the front lens grouping rotates to control focus. A full twist from 2.5 feet to infinity requires about a 3/4 turn of the element. A depth of field scale is printed in red numbers above the shutter and can be seen while looking down upon the shutter with the camera at waist level.

Near the 2 o’clock position around the shutter is the manual cocking lever which must be activated before each exposure. The Pony lacks double exposure prevention, so you can cock and fire the shutter over the same piece of film as many times as you want (or don’t want). Below the cocking lever, near the 4 o’clock position around the lens is an ASA flash sync post for attaching an appropriate flash sync cord. Finally, near the 10 o’clock position around the shutter is a cable release socket for attaching a cable release. The Pony lacks a self-timer, so you could also use this socket for an auxiliary self-timer unit if you so wish.

Collapsible Lens Warning: One last thing is that the Kodak Pony Model C is the only in the first generation Pony series that does not have a collapsible lens, so if you are reading this review, but your Pony is not the Model C, you will need to remember to pull out and twist the entire shutter and lens assembly into the taking position before using the camera. While writing this review, I had access to a Model B and 828 Pony, and I can confirm that the shutter release button cannot be pressed with the shutter collapsed.

The viewfinder is a simple, straight through optical design. There are no frame lines visible, rangefinder, or any indication of any of the camera’s settings. At the time of the Pony’s release, simple scale focus cameras like these were still very common and would not have seemed like much of a con to the camera’s market. The Model C is the only Pony with a 44mm lens, compared to a 51mm focal length in earlier models. This difference in the Model C’s lens offers greater depth of field, meaning that guess focusing was much easier.

Comparing the depth of field scales on the Model C and an earlier Model B, when both cameras are set to f/11 and the focus distance set to 10 feet, the model C will sharply capture anything from 50 feet to about 5.5 feet. At the same settings, the Model B will sharply capture from 25 feet to about 7 feet.

The Kodak Pony is a simple, yet well built camera with an attractive symmetrical body, a capable lens and shutter, and sold at a price that could be afforded by most people. The formula clearly worked as the Pony sold well throughout the decade-plus it was available. Many of these cameras can be found today in good condition for very little money, usually requiring a quick wipe down to be ready for use again. Is the Kodak Pony worthy of your time and pocket change? Keep reading…

Kodak Pony 828

The first camera in the Pony series when it first launched in 1949 was the Pony 828. Using Kodak’s 35mm roll film format, 828 offered a larger exposed image size of 28mm x 40mm than regular 35mm film, but sacrificed the number of exposures to only 8 per roll. At the time of the Pony 828’s release, Kodak offered a number of films in 828 format, from color films like Kodachrome, Kodacolor, Plus X, and Super XX.

At first glance, the 828 and 35mm versions of the Pony look pretty similar, but there are quite a few differences as the camera’s entire film compartment and controls had to be redesigned for 35mm film.

Externally, apart from the model number “Pony 828” printed above the lens and shutter, the most obvious differences are the lack of a film rewind knob on the top plate, making for an asymmetrical design. Film transport on the 828 cameras is right to left instead of left to right on the 35mm models, so the 828’s film advance knob is where the 35mm’s rewind knob is. In place of a knob on the other side of the top plate is a film type reminder dial.

Around back another obvious change is the presence of the green peep hole, which allows you to read the exposure numbers printed on the backing paper of the 828 film. Since 828 was a roll film format, it is sandwiched between a layer of paper like other roll film formats. The need for this hole means there is no exposure counter on the top plate of the camera. Also, the two controls on the back of the camera for advancing and rewinding the film are also missing.

Film transport on the Pony 828 is right to left, instead of left to right on the 35mm versions, which also means the clasp for removing the door is also reversed from the 35mm camera.

After removing the film door, you see the simplified roll film compartment. After exposing a roll of 828, you would move the empty take up spool from the right side to the left and then load in a fresh roll of 828 film on the right. Also notice that the film gate is much larger than that of the 35mm camera, allowing for larger exposures.

Overall, the Pony 828 is still the same camera as it’s 35mm versions. Both have the same size bodies and weigh nearly the same weight. The 828 version has the same collapsible lens and shutter as the first two versions of the Pony 135, and all models share a similar turquoise/gray top plate and molded plastic and metal body. For the novice photographer looking for a simple camera, the 828 version was $5 cheaper and also used more affordable film, but whether or not the economy of 20 or 36 exposures instead of 8 would have been the deciding factor on which one to buy.

Here is a full width scan of three shots done using this Pony 828 using cut down Kodak Portra 160. Despite 35mm and 828 using film stock of the same physical width, the lack of perforations on 828 means that larger 28mm x 40mm images can be made, offering 30% more detail.

Finally, here are some left over images of the Kodak Pony 828 to give a little more detail into the camera’s design.

My Results

The first Kodak Pony I ever used was actually the Pony 828 which I had acquired back in 2017. At the time, I had a small supply of respooled Kodak Portra 160 cut down to 828 size and I shot it later that fall. Since 828 is the same width as regular 35mm, I was able to process this at home using a regular 35mm spool in my Paterson tank.

As best as I can tell, the Pony 828 uses the same 51mm Anaston lens as the Pony 135 Models A and B, suggesting the images should be of better quality, but the larger size of the 828’s 28mm x 40mm negatives gives them a slightly more wider angle view, plus with an additional 30% of image area, the Pony 828’s images show a bit more detail, especially when seen at full size on a computer monitor. Look at each image in the gallery above at full resolution on your desktop, and there’s quite a bit more detail than you might expect from what otherwise was a very simple camera.

That single roll of hand cut 828 would be the only roll I shot in the Pony 828 camera, the rest being in the 135 Model B that Alyssa asked me to fix and then my own personal Model C. For Alyssa’s camera, I loaded in a very short strip of bulk TMax100 and shot the five black and white images in the gallery below with that combination, and then the color images below in my Model C with semi-fresh Fuji 200.

The larger size of 828 film in the Pony 828 offers more detail than an equivalent 35mm image would, but the wider and faster f/3.5 Anaston in the Model C seems to have bridged that gap as the images I got from my Model C seem to be improved upon from Alyssa’s Model B with the slower f/4.5 Anaston.

Although both Anastons are 3-element designs, I have to assume that some internal improvements were made to the later lens, perhaps optically or in the lens coating as the images show a level of sharpness from corner to corner you’d expect from higher specification lenses. In fact, after scanning in the roll from the Model C, I had to triple check my sources to make sure this wasn’t some kind of 4-element Tessar design.

Optically, these images are wonderful and speak to how good Eastman Kodak was at making simple cameras that made good photos. Considering a bulk of Kodachrome slides were shot on cameras just like this, they had to be good enough to be able to make images that could stand up to being projected onto a large projection screen.

Another benefit from the slightly wider Anatason on the Model C is increased depth of field, which makes guess focusing easier. The f/stop marks on the depth of field scale on the Model C are spread farther apart than previous models, and completely eliminate any markings for f/22 even though that is an option on the lens. I found that while shooting kids running around during an Easter egg hunt, I had no problem getting them in focus, even though the skies were heavily overcast and I was using a 200 speed film. I never bothered to try any indoor shots, but opening up the lens would have still allowed me a decent amount of flexibility for group shots of 10 feet away or more.

Optically, almost everything is great except for a couple strange light leaks that I found on a few photos in the dead center of the image. I included two shots, one of the utility pole with all the nails in it and the other of the White Castle building. In both cases, the sun was out, but I made other shots in sunlight that don’t have this leak. The Model C doesn’t have a collapsible lens, so I can’t imagine it came from there, and had this been a light leak around the door, you’d think it would have been more prevalent.

Beyond the images, there’s not a whole lot more to say about the Pony as they’re simple cameras. You guess your exposure and your focus distance, set everything in advance, remember to cock the shutter, and fire away. For someone used to more automation, this camera likely would feel like a strange beast, but for anyone used to early to mid 20th century cameras, you should feel right at home. The Kodak Pony is comfortable to use, has a big enough viewfinder so that those with prescription glasses won’t struggle to use it, and assuming you get everything right, you’ll be rewarded with complete rolls of really nice looking photos. Assuming I can figure out that light leak, I could see myself coming back to this camera again and again.

I know that simple Kodak cameras like this aren’t for everyone and there’s likely little I can say to change the minds of anyone who already isn’t interested in a camera like this, but for the small number of you on the fence about an attractive mid century American camera with a great lens, this is definitely a camera worth your time. As an added bonus, you can find these dirt cheap on eBay and perhaps even at local garage sales. I keep talking about the Model C, and while I do believe it to be the best of the series, almost everything I say here applies to the earlier models. Both the Pony 828 and the Model B that I repaired for Alyssa had the slightly longer and slower lens, yet I still managed to make impressively sharp and in focus images.

Eastman Kodak hit a homerun when they designed the Kodak Pony in 1949 when the first model was released, and the success of that original model still holds true today, 73 years later. These are wonderful cameras that are still worth shooting today. I had high hopes for this camera before shooting it and was still impressed with the results after, and I think you would be too.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Pony_828/135

https://blog.jimgrey.net/2018/11/16/kodak-pony-135-model-b/

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2017/06/06/ccr-review-64-kodak-pony-135-model-c/

https://digitalfilmnerd.wordpress.com/2018/01/27/review-kodak-pony-135/

https://filmphotography.eu/en/kodak-pony-135-model-c/

https://pheugo.com/cameras/index.php?page=pony

https://filmphotographyproject.com/kodak-pony-1950s-little-work-horse/

Wisconsin cheese curds and mini-donuts: YUM! The model C and the pricier model IV are plentiful on eBay, so I guess I’ll pony up a Jackson and get one.

They’re a bargain for $20!

I like the left right symmetry of the design. $33 at the time is an impressive achievement. It is certainly not up to the precision and craftsmanship standards of their German Retina cameras, but was not aimed at that audience.

Thanks for this! My first camera when I was 8 or so was a Pony 135, though don’t know if it was a C or not. It’s somewhere in my dad’s basement hoard. Tied to find it on visits but it’s hopeless. Found a nice one in great shape a while back for very little money. Put film in it and will see how things turn out in a few years. Learned a lot with that one and I felt like a pro shooting and processing 35mm.

Great story, Jeff! All the Pony’s were nice cameras. Kodak did a really good job of maximizing image quality with a good lens on a basic camera. They knew that if someone bought a Kodak camera and got good images from it, they’be more willing to buy Kodak film, which was their real bread and butter.

Great post. Pony Model C was also made in Toronto, by Kodak Canada.