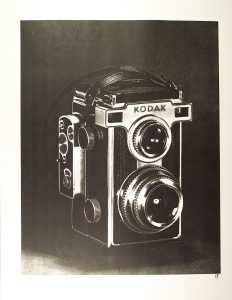

This is a Kodak Reflex II, a Twin Lens Reflex camera made by Eastman Kodak in Rochester, NY between the years 1948 and 1949. It was an update to the original Kodak Reflex from 1946 offering several upgrades including a standard 4-element Anastar lens, brighter viewing lens, Fresnel focusing screen, and an exposure counter. All Kodak Reflex cameras shot 2¼ x 2¼ inch images on 620 roll film, but an adapter to use 828 film was also available. It is a solidly built camera with a diecast aluminum body and a competitive feature set. The Kodak Reflex was produced at a time when cameras like the German Rolleiflex and Rolleicords were not available for purchase, so for a brief moment in time, the Kodak Reflex and Reflex II was one of the highest spec TLRs you could buy.

Film Type: 620 Roll Film (twelve 2¼ x 2¼ inch exposures per roll), (optional 828 mask was also available)

Lens (Taking): 80mm f/3.5 Kodak Anastar coated 4-elements in 4-groups

Lens (Viewing): 80mm f/3.5 Kodak Anastar coated 4-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Waist Level Coupled Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Flash Kodamatic Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1/2 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Kodak Flasholder with M and F Bulb Sync

Other Features: Sports Finder, Automatic Exposure Counter

Weight: 754 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_reflex_ii.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kodak Reflex II was the follow-up to Kodak’s first Twin Lens Reflex, produced immediately after the war to fill the void of German TLRs which were not being made at the time. It uses a simple, but reliable external gearing to couple the taking and viewing lenses together, and on this example, has 4-element Kodak Anastar lenses which were known for producing images of good quality. The camera has an automatic exposure counter, a bright and useful viewfinder and flash synchronization, but the best part was its affordable price. If you were in the market for a TLR in the late 1940s, the Kodak Reflex II was for you! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.1 | ||||||

History

In the years immediately before, during, and after World War II, Eastman Kodak took up the task of not only supplying the United States military and private sectors with photographic film, but also premium cameras for the war effort and domestic use.

In the years immediately before, during, and after World War II, Eastman Kodak took up the task of not only supplying the United States military and private sectors with photographic film, but also premium cameras for the war effort and domestic use.

Cameras like the Kodak Medalist and Ekta were not only designed with military and professional use, but these were also some of the most highest spec cameras money could buy, regardless of which company made them. The 5-element Kodak Ektar lens used in the Medalist was one of the sharpest lenses in the world, and larger version of the Aero-Ektar were so good, they were mounted to military aircraft and used for aerial reconnaissance in Europe.

The Ektra was a premium 35mm rangefinder camera, with a feature set that matched and even exceeded the best of what Germany had to offer. The Ektra had features that neither the Leica or Zeiss-Ikon Contax could boast, such as a interchangeable magazine film backs, rapid film advance lever, infinitely adjustable viewfinder with support for telephoto lenses as long as 254mm, and an extremely long 104mm rangefinder base which was wider than any rangefinder base offered on any camera being made. Six different lenses were designed for use on the Ektra, all of which had Kodak’s best optics, and each featuring lumenized lens coatings on all elements, something that no one else was doing at the time and would not become common practice in lens design until the 1960s.

During the time which the Medalist and Ektra were in development, Eastman Kodak researched a whole host of potential new designs, including what would have been the company’s first ever 2¼ x 2¼ Twin Lens Reflex. In a 1939 document entitled Major Developments in New Apparatus, Kodak previewed a new TLR simply called the 6x6cm Reflex Kodak (E-192).

Had the Reflex Kodak been made, it would have been one of the most innovative and exotic TLRs ever produced. The base lens would have been a 6-element 80mm f/2.3 Anastigmat Ektar and it would have featured both a coupled rangefinder and waist level finder with automatic parallax correction. The camera would have also offered a selection interchangeable lenses, a focal plane shutter, interchangeable film back including support for both roll and sheet film sizes, and all the premium features included on other TLRs such as an automatic stop film advance, exposure counter, double exposure prevention, and a sports finder.

Sadly, the camera was never built and the single image seen to the left is the only known image of this over the time “Rollei killer”.

When the war was over, Eastman Kodak continued production of both the Medalist and Ektra making it available for purchase by anyone with deep enough pockets. In the case of the Medalist, the camera was updated as the Medalist II with some features that they thought would make it more appealing for non-military use.

If having a steady supply of American made photographic gear was important during the war, it was even more so after as Germany’s manufacturing and export capabilities were completely destroyed. It would take nearly five years after Germany’s surrender in May 1945 before German goods could be reliably imported into the United States, so for photographers needing a new Leica rangefinder or Rolleiflex TLR had to find options elsewhere.

Although the Leica had been around for well over a decade by the end of the war and it had dramatically increased in popularity, for professional and advanced amateur photographers, the 2¼ x 2¼ TLR was still the camera of choice. The larger negative and familiar design of the Rolleiflex and Rolleicord would remain in high demand until well into the 1950s when 35mm rangefinders and eventually 35mm SLRs took over.

For American photographers wanting a brand new 2¼ x 2¼ TLR, two companies answered the call to build a premium option to take the place of comparable German models, Ansco, and Eastman Kodak.

Kodak was the first out of the gate with the Kodak Reflex, and in 1947, Ansco answered with the Ansco Automatic Reflex 3.5. Ansco’s option took a little while longer to reach the market, likely because of how different it was than any Twin Lens Reflex ever made. The camera eschewed the traditional controls of German models and came up with a moving bed design with unique side controls for cocking and firing the shutter, a high quality 83mm Wollensak f/3.5 lens, unique film advance lever, automatic exposure counter, and a few other premium touches. The camera looked and worked unlike any TLR ever made and carried a premium price. In a 1948 ad from the US retailer Montgomery Wards, both the Kodak Reflex and Ansco Automatic Reflex 3.5 were sold on the same page for $137.92 and $275 respectively. With a price that was almost exactly twice as expensive, Ansco’s camera was a much harder sell.

For Kodak, the Kodak Reflex had a simpler design, using externally coupled gears to focus the twin lenses. While not as elegant as a folding bed design, it cost less to produce but also had the benefit of being more reliable. Folding bed designs can become out of alignment if the camera is dropped or takes a hard enough bump to the front, whereas the geared coupling is very difficult to come out alignment. The Kodak had a feature set more reminiscent of the Rolleicord, with a film advance knob, no in-body exposure counter, and a 4-element Kodak Anastigmat taking lens. On the plus side, the Flash Kodamatic leaf shutter was fully flash synchronized, and the triplet lens was above average, producing images of good sharpness.

Shortly after its release, a slightly upgraded version called the Kodak Reflex Ia came out which upgraded the viewfinder screen to what Kodak called the Ektalite Field Lens, which had a Fresnel pattern which dramatically improved brightness.

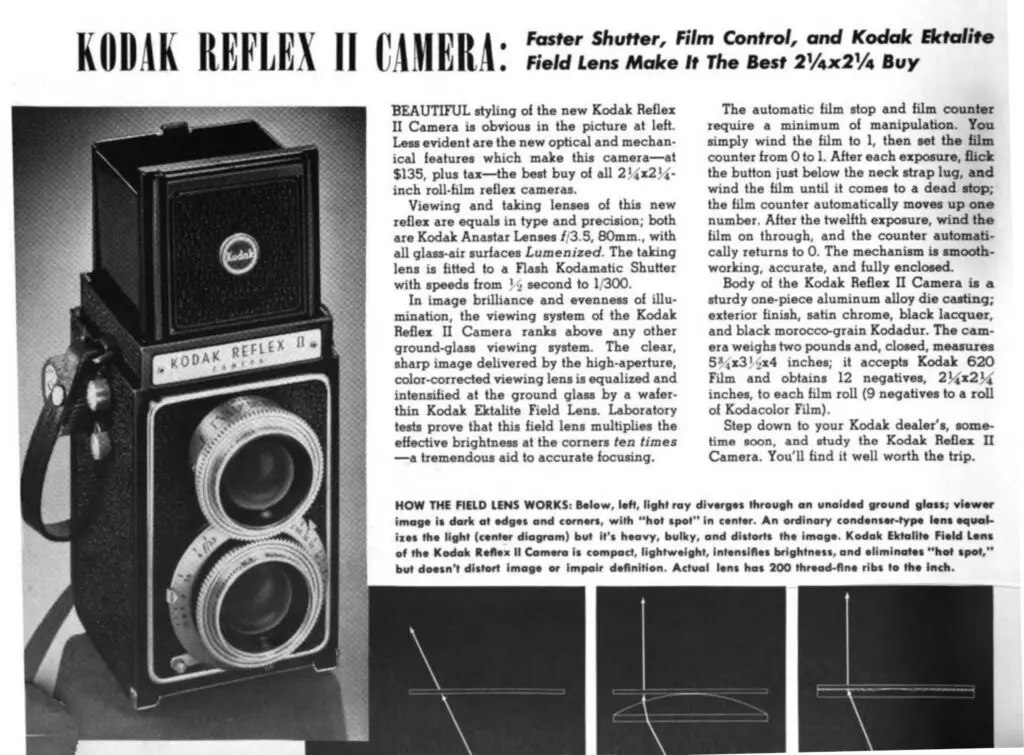

Finally, in 1948, a model called the Kodak Reflex II was released which included the upgraded Ektalite Field Lens, but also upgraded both the viewing and taking lenses to higher quality 4-element Kodak Anastar lenses (the earlier Kodak Reflexes had a 4-element Kodak Anastigmat lens, but it is not clear if it was the same lens), a new shutter with top 1/300 speed, and an automatic exposure counter. The new features came with a very similar $135 price, which was still a far cry from the Ansco.

Although lacking in the prestige offered by a German camera with desirable Zeiss lenses, the Kodak Reflex had an excellent lens, good build quality, a much more affordable price, and if that wasn’t enough, you could actually buy it!

In a short review of the camera from the March 1949 issue of Popular Photography, the camera was rated as a best buy with high marks going to the bright Ektalite Field Lens which was claimed to improve brightness in the corners by ten times, the Anastar lens with Lumenized coating, and the new exposure counter. It was likely pretty clear to anyone looking to buy a camera in this segment that although not a German design, that Kodak did not skimp on features or quality, the Kodak Reflex II was a very capable photographic instrument.

It is difficult to measure the success of the Kodak Reflex series. On one hand, these were well built cameras that produced good quality images, were easy to use, supported by a major company, and were affordable, yet history tells us they were only made for a few years. It seems that Eastman Kodak chose to make these as a stopgap until imported TLRs from Germany and elsewhere became common and then they immediately stopped making them. Everything I’ve read suggests that by 1950, these cameras were no longer made, suggesting either that they sold poorly, or that Kodak just really didn’t want to be in the TLR business and exited it as quickly as possible.

Although Kodak would never again make a true TLR, they would however continue making inexpensive twin lens box cameras like the Duaflex, Brownie Starflex, and many others. Each of these models were extremely basic box cameras, usually with single or two speed shutters, and a very large waist level finder up top that was not coupled to the taking lens. Whatever their reason for it, Eastman Kodak knew what they were doing as they continued to dominate the film market for decades to come. It is a shame though as the Kodak Reflex series had promise, and it would have been interesting to see what a third model in the series might have been like.

Today, few people even remember Kodak once made a true TLR, and of the people who do remember, I doubt any Kodak Reflex is anywhere near the top of their wish lists. These cameras aren’t super common, even in the United States, suggesting that not a lot of them are out there, but even when they are, they rarely go for much. For anyone who is a Kodak completist, or someone who just wants to try something different, give one a try. They’re pretty easy to use, and since their demand is low, prices are usually reasonable.

My Thoughts

Kodak is famous for making a large number of different camera styles, box cameras, folding cameras, rangefinders, SLRs, point and shoots, even instant cameras. When it comes to twin lens cameras, most of Kodak’s offerings were of the twin lens box camera style like the Kodak Duaflex in which the viewfinder lens was not coupled to the taking lens, so it couldn’t be used for measuring focus like with a traditional TLR.

For reasons we’ll likely never understand, Kodak did not compete in the true Twin Lens Reflex market with only one exception, the Kodak Reflex and Kodak Reflex II from the late 1940s. The need to make a capable, but affordable TLR immediately after the war was emphasized by the lack of German TLRs coming into the country. In September 2018 I wrote a review for the ANSCO Automatic Reflex 3.5 which was a premium TLR produced at the same time as the Kodak Reflex. Shortly after that review went live, I had the idea to also review the Kodak Reflex as it was a more affordably priced alternative to ANSCO’s premium TLR. Little did I know that it would take me over 5 years before I would actually get to that review!

The delay in getting a Kodak Reflex was not due to lack of interest or financial reasons, rather that they seem to be difficult to find in good condition. Either Kodak Reflexes were so popular, most are in terrible condition today, or the cameras were so poorly built that even lightly used copies didn’t hold up well. Add to the fact that if I was going to review one, I wanted the highest spec model, the Kodak Reflex II.

The day would finally come in early 2023 that I got a decent looking and working Kodak Reflex II which I could review. Upon unwrapping the eBay box that it arrived in, I was pleased to feel that the Reflex is a very solid TLR and doesn’t at all feel any cheaper than similar design cameras made in the US, Germany, or Japan. At 946 grams, the Kodak Reflex II is only a few grams lighter than a similar Rolleiflex at 988 grams, but quite a bit lighter than the much heavier ANSCO Automatic Reflex at 1282 grams. Build quality felt good, and with the simpler, but more rugged geared lens coupling, there was no wiggle of the front standard like you often see on lesser TLRs.

Looking down upon the top of the camera with the viewfinder hood down is a bright red circular Kodak logo, not entirely unlike that of other “red circle logo” companies like Leica, Petri, and a few others. This is one area in which the Kodak Reflex II looks better than the earlier versions as all others have a simpler stamped Kodak logo in the metal with no leatherette body covering. In front of the viewfinder, atop the viewfinder lens is the focus ring with depth of field scale. Since the viewfinder and taking lenses are geared together, you can rotate either one to change focus from a minimum distance of 3.5 feet to infinity. The depth of field scale has lines for the maximum aperture of f/3.5 all the way down to f/16.

Around back, the camera has a red window with a spring loaded lever that is connected to a door which blocks light from passing into the film compartment. In order to read the exposure numbers on the film, you need to move the lever to the side to open the window. Since the Kodak Reflex II has its own built in exposure counter, you only need the red window to set the first exposure, but after that, you can use the camera’s counter for the rest of the roll. Above the door are two round buttons that when pressed in the direction of the arrows, releases the door lock, allowing access to the film compartment. Above the door lock is a small button used to release the viewfinder hood.

Each of the sides of the camera have a metal loop near the top which allows for the camera to be hung from a neck strap with or without the original leather case. The left side has the flash sync port in the middle with a small post for a Kodak flash gun. Below the sync port is a small post for stabilizing the flash and a threaded hole on the opposite side, whose purpose is not clear.

On the right side, there is a combination film advance knob with film reminder disc and the exposure counter window. A post to the right of the counter window has a threaded ring around it which allows you to manually turn the exposure counter. This is needed when loading in a new roll of film to get the number to 1, or if film is removed before the end of a roll, to reset it. Under normal operation, you can only turn the exposure counter one number before a lock prevents you from going any further. A separate post above the reset knob can be pressed up to circumvent this lock, allowing you to freely turn the exposure dial to whatever number you want.

Up front, the Kodak Reflex II has controls for the shutter speed, aperture, and the shutter release. For those of you (like me) who don’t always read the manual before picking up a camera you’ve never handled before, let me help you not make a mistake I did and fail to realize that the shutter on this camera is not coupled to the film transport. This means that advancing the film does not cock the shutter for you, you must do this in a separate step.

To cock the shutter, you use the shutter release, except press it in the opposite direction you would to fire it. This method is similar to early Rolleiflexes in which the shutter release also cocks the shutter, the only difference is in the location of the lever. Pull up on the lever and press down to fire it. This camera has no double exposure prevention, so you can do this as many times in a row as you wish, re-exposing the same frame over and over. Changing the shutter speeds and f/stops is pretty straight forward. The shutter speed selector does not have click stops, however the aperture selector does.

The viewfinder looks similar to most 6×6 Twin Lens Reflexes of the 20th century, however there are no etched grid lines or any type of focus circles in the center. Just a flat piece of ground glass with a Fresnel pattern to increase brightness. Kodak called this type of focus screen the Ektalite Field lens, and it does work quite well, especially when compared to other late 1940s TLRs. It is not as bright as those from the latter half of the 20th century with laser etched screens, but it is very good.

Also like most 6×6 TLRs, the Kodak Reflex II has a swing up magnifier which is hinged on the back edge of the hood. I prefer back edge designs like this as opposed to ones that are on the front lid, as I feel they’re easier to open and close. With the magnifier up, a small square hole on the back edge of the hood allows you to see through the front lid by pressing in and up to reveal a sports finder. Sports finders on TLRs are ideal for fast action shots at or near infinity, where exact focus isn’t necessary, but your ability to compose a bright and upright shot quickly is. Closing the viewfinder requires pressing in on the sides first, then the rear, and front lid last. While this system works fine, it is not as elegant as the double hinged ones used by premium German and Japanese TLRs like the Rolleiflex and Minolta Autocord.

There is a lot to like about the Kodak Reflex II. It is clearly not a top tier TLR loaded with features to match the best of what Germany had to offer. But it doesn’t have to be. The Kodak Reflex II was meant to be an economic model that was just good enough to give you excellent images without too many features that would drive up the price. Kodak did with this camera exactly what they did with their other mid century cameras like the Kodak Tourist and Signet series, package a great lens in an easy to use body at an affordable price. While many collectors and film enthusiasts will likely be drawn to higher end German and Japanese models, the Kodak Reflex II should still make some really nice images, right? Keep reading…

My Results

When I first got the Kodak Reflex II, I tested the shutter and all seemed to be in good working condition, so I set it aside to get some film loaded. When it came time to shoot it, I noticed that the shutter seemed to be slowing down from the last time I tried it out. If I fired it several times in a row, it would work OK, but if I let it sit for even a minute, it would slow down, so I took some naphtha oil and squirted it onto the blades to loosen it up, and that seemed to do the trick, at least for a while. I figured I could quickly load in some film into the camera and shoot an entire roll in a day and hopefully things would be loose enough to not give me any trouble. Just in case it did however, I didn’t want to risk ruining any fresh film, so I respooled a roll of roughly 20 year expired roll of Kodak Portra 160NC onto a 620 spool and took it out shooting.

Well, there’s good news and bad news. The good news is the shutter actually seemed to fire correctly throughout the entire roll, I didn’t have a single blank image or any that look grotesquely overexposed. More good news is that the lens generally seemed to return sharp images that likely would have pleased anyone looking for an affordable American TLR in the years following World War II.

The bad news is that the Kodak Portra 160NC held up very poorly. I’ve had mixed results with expired Portra, sometimes I get good images with a slight color shift, other times I get terribly muted colors with strange streaks running through the middle and an overall yellow cast to the entire image.

More bad news is that I seemed to struggle with focus on this camera. Being a gear driven TLR, it is unlikely the taking and viewing lenses have become uncoupled, and the fairly bright viewfinder should have allowed me to see accurate focus, so the only thing I can think of is a film flatness issue. After unloading the camera, I inspected the film pressure plate and it didn’t seem to be defective or out of position, so I don’t really know what happened. It just seems as if time has taken its toll on this camera and it is in dire need of service, something I am unwilling to spend money on.

Shooting the camera was an okay experience. If its my turn to go to “camera confession”, I don’t love shooting TLRs, at least not top tier models. The Kodak Reflex II had no fundamental flaws, I just didn’t really enjoy the experience, and despite rushing through the roll in a single day, I still felt like I couldn’t wait to finish the roll. Then, upon seeing the poor results, any desire to give this camera another go went completely out the window. It is plausible I might have gotten better results from a second roll, but I didn’t need to see anymore results to form my opinion.

This is the part of reviewing old cameras that infuriates some people. They get frustrated with me that I’ll do an entire review having only shot a single roll, or even a partial roll on a camera that clearly doesn’t work. For those people, I say, hopefully you got enough out of the rest of what I write to still enjoy reading my reviews, but despite what probably seems like an endless supply of cameras for me to review, they can’t all have CLAs.

I will acknowledge that I generally like mid century Kodak cameras. The Kodak Medalist and Ektra are two of my favorite cameras, and they make wonderful photos. I have complete confidence that had I picked up a perfectly working, mint condition Kodak Reflex II, I likely would have gotten great images from it. In the era this camera was made, Kodak made great lenses and the 4-element Anastars here are no exception, but the rigors of nearly three quarters of a century are tough, and this camera hasn’t fared as well as it could have.

Perhaps I should have waited for a better sample to come along and not pushed this out, but if I’m being perfectly honest, other than getting better looking results, the rest of what I’ve typed would have been the same.

So if you can put on your imaginary caps for this one and ride the Trolley to King Friday’s castle, I can imagine a good working, and solid built mid century American TLR with a brighter than average viewfinder, easy to use controls, and a lens that produces images with good sharpness, contrast, and color reproduction. I suspect there probably would have been a slight amount of softness and maybe some mild vignetting in images where the sky was visible, but nothing to complain about.

I think the Kodak Reflex II is a solid camera, and deserving of being in my collection, it just so happens that this particular example wasn’t the best sample to test. As always, your mileage may vary, so if you have one that works great, and you’ve shot some photos with it you’d like to share, include a link to them in the comments below!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Reflex_II

https://casualphotophile.com/2021/09/09/kodak-reflex-ii-review-a-rollei-competitor/

https://mattsclassiccameras.com/tlr-box/kodak-reflex-ii/

https://mikeeckman.com/photovintage/vintagecameras/kodakreflex2/index.html

http://www.historiccamera.com/cgi-bin/librarium2/pm.cgi?action=app_display&app=datasheet&app_id=1130

It’s very possible the taking and viewing lenses are out of sync. You can check by focusing an object (the proverbial newspaper taped to the wall) about 7 feet away on a ground glass at the film plane and then looking to see whether the object is in focus on the viewing screen. Use an 8x or 10x magnifier to check focus.

Nice to see another Kodak getting some love, Mike. The Anastar lenses are what were once called Anastigmat Specials (so 4-element), and are “Lumenized” (coated) as the Popular Photography article mentions. Original Reflex model’s lenses were Anastigmats (3-elements), later called Anastons. A kit containing an Ektalite screen, viewfinder mask and a new nameplate was available from Kodak to turn a Reflex into a “Reflex 1A”. Nevertheless, the Reflex II is, to me, still a better package. As for the mystery threaded hole on the side, Reflexs required a special Kodak Flasholder with an L-shaped bracket – a thumbscrew is tightened down into that hole, a little locating pin fits into the other, while the cable plugs into the socket.

Please don’t just squirt naphta onto the shutter leaves and leave it like that, this way you just move the dirt to another place.

If you got the leaves exposed anyway, it’s easy enough to take a q-tip and actually remove what is slowing them down.

I have six of these cameras, both first and second, and all of them have issues with synchronization of the viewing lens and taking lens. Several have the teeth slightly worn so the two gears skip by each other. I have still been unable to get the lens ring separated from the lens despite taking out the screws. Pushed on/ off or screw on or off? Who knows. I could then dial in each lens but once the gears go back some will skip. I have had them for 20 years now and look at them now and then, fool around with them, and then put them away.

A few comments:

The “Kodak Reflex IA” models, were factory reconditioned model I’s, which were returned to kodak and fitted with ektalite field lenses. It was a big enough development that 30% of the first generation models were refitted with the fresnel.

The “myserious threaded hole” on the left side of the camera, is for a dedicated accessory. Kodak sold a version of the model B flasholder with a pin & screw right angle bracket just for the reflex I & II. While a flash could be mounted to the bottom tripod mount, i think kodak was worried about the camera’s sturdiness in some areas.

In particular I find the back door on the reflex to be somewhat flimsy. It’s not sufficiently stiffened to resist getting bent, so some examples the door doesn’t seat correctly or has a lot of force to latch/unlatch.

While the reflex wasn’t particularly long lived, it’s marketing cycle continued into 1951-52, around the time the chevron was brought to market, which was intended to supersede it, with a better designed advance & film metering mechanism, and better shutter & optics. But retaining the support for 828.

However both cameras would be advertised with kodak’s ill fated Ektalux flash system, along with the signet 35, medalist, tourist, and pacemaker graphic. But interestingly kodak only made a dedicated bracket for the graphic and the polaroid land camera, as they had waning interest in supporting the reflex.

My current theory is that kodak’s shutter’s weren’t up to the task in the late 40’s, as they had to rush flash support for the supermatic by re-engineering the self timer mechanism into a synchroniser escapement. This hacked together solution on the kodatic & supermatic meant they were behind the technology curve of the ilex acme synchro, and the wollensak rapax semi and fully synchromatic shutter that became commercially available in 1947. And unlike the compur shutters which came in variants for different types of integrations; kodak had to hack together a solution for each new product (medallist, reflex, monitor, etc.) Which is why the reflex didn’t have the better supermatic shutter. So kodak decided they needed to redesign their shutter lineup from the ground up, hence the “synchro” series from the 50’s, (synchro 200, synchro 300, synchro 400, synchro-rapid 800), but the older supermatic proved more reliable, and I think kodak’s ambitions of more sizes of synchro-800 never materialised. (Graflex meanwhile started to worry that their dependence on kodak and wollensak was becoming a liability, when they stopped selling shutters, and wollensak got bought by revere). So they started to make the synchro-1000 shutter on similar principles to the 800, but in house.

It’s not a stretch to imagine that kodak had plans for other products with that higher spec 800 shutter, beyond the graphic, tourist, and chevron, but it’s long term reliability, cost, and complexity as well as the growing quality of competition dampened those plans. Likewise can be said of Graflex, both with the synchro-1000 & the graphic jet (they had plans for a 6×6 slr built around the jet drive and their new shutter.) It’s also not a stretch to think that kodak had plans for a more competitive reflex model but had trouble justifying a higher cost product, especially with the failure of the ektra II due to cost.

It’s also worthwhile to acknowledge, that Kodak planned it’s product offerings alongside it’s subsidiary Kodak AG, and they had briefly offered a higher spec 620 models, with the Regent II, Vollenda II, and Suprema. With production priorities focused on the retina, their efforts to build out these other higher spec models never resumed production, but they likely had planned to.

The ciroflex Models E & F (and later graflex 22 model 400), were pretty comparable in price also, but had better shutters, but flimsier construction, and the models b,c, and d, were really selling better due to their cheaper price point. So while kodak probably expected better sales over the ciroflex, (and argoflex), they probably didn’t capture the market like they expected.

Either way, the Reflex models exist in a really interesting time when Kodak was still considering higher end models, before retreating from the high end by the mid 60’s.