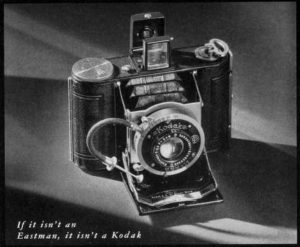

This is a Kodak Vollenda 48, a folding camera that shoots 3cm x 4cm images on 127 film. It was originally made by Nagel Kamera-Werke and later by Kodak AG in Stuttgart, Germany between the years of 1929 and 1937. The Vollenda was one of Dr. August Nagel’s models that he designed at his own company and brought over to Kodak when he merged with them in 1931. Like all Nagel designed cameras, the Vollenda was a high quality and compact camera that had an excellent lens and a very capable shutter.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (sixteen 3cm x 4cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 5cm f/3.5 Schneider-Kreuznach Radionar uncoated 3-elements

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Flip up Reverse Galilean Scale Focus Finder

Shutter: Compur-Rapid Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Manual: None

History

The Eastman-Kodak company was originally founded by George Eastman in 1888. George Eastman was a visionary inventor and businessman who had the idea that if they could sell an inexpensive photographic film apparatus that would require customers to keep coming back to buy more film, they stood to make far more money than they would as a dedicated camera making company. Instead of getting one purchase from a customer for one or two cameras, they could have a customer for life, continually buying film.

The Eastman-Kodak company was originally founded by George Eastman in 1888. George Eastman was a visionary inventor and businessman who had the idea that if they could sell an inexpensive photographic film apparatus that would require customers to keep coming back to buy more film, they stood to make far more money than they would as a dedicated camera making company. Instead of getting one purchase from a customer for one or two cameras, they could have a customer for life, continually buying film.

Eastman’s business model was a roaring success, and it catapulted Kodak to the top of the film industry for over a century. While Kodak was always a ‘film first’ company, they didn’t ignore the camera making business either.

Kodak’s first cameras were basic box cameras with simple lenses and single speed shutters. These early box cameras were designed in a way to be cheap to manufacture, and easy to use, but just good enough that people would be satisfied with the images they made. Over the first half of the 20th century, Kodak would on occasion release mid to upper priced models to complement the basic box cameras, but they generally weren’t considered leaders in the camera making business.

By the late 1920s, if you wanted film, you might buy it from Kodak, but if you wanted a high end camera, you bought something from Germany. While Kodak had a variety of capable models at this time, they sorely lacked the precision and expertise of the German marques like Zeiss, Voigtländer, and Leitz. For this, they turned to a man named Dr. August Nagel. If George Eastman was the most important man in Kodak’s history, Nagel was second.

August Nagel was born in June 5, 1882 in Stuttgart, Germany. (There is at least one article online which suggests Nagel was born in 1867, which I do not believe to be true.) In his younger years, he worked in various small machine factories learning business and the inner workings of mechanical objects. Despite being a skilled mechanic, Nagel’s passion was photography, and he would devote his free time to the design and construction of primitive cameras.

In 1908, at the age of 26, he founded his first company with childhood friend Carl Drexel, called Drexel & Nagel of Stuttgart. Drexel & Nagel’s first camera was a very compact camera called the Contessa No.1 which made 4.5cm x 7cm images on what I can only assume was some type of early roll film. In my research for this article, I was not able to find any images or any other information about what this first Contessa would have looked like.

Drexel & Nagel saw almost immediate success, and in 1909, renamed itself to Contessa Camerawerke Stuttgart, and by 1910 had developed as many as 23 different models, many of which were exported all over the world.

By the start of World War I, Contessa Camerawerke employed over 500 people, and during the war, would switch production to making armaments for the German war effort. After the war had ended, the German economy was in disarray and many German companies were unable to stay in business. One of these companies was Nettel Camerawerk from Sontheim am Neckar, Germany. Nettel had been in business since the early 1900s as a maker of folding medium and large format cameras.

In 1919, Contessa Camerawerke would take over the floundering Nettel Camerawerk and become Contessa-Nettel AG. An early Contessa-Nettel model was called the Cocarette which was a folding bed roll film camera that had a unique film loading design in which the film compartment would slide out of the bottom of the camera as it’s own separate piece. A new roll of film would be installed onto the spools and the entire film compartment would be slid back into the body of the camera. This guaranteed a near light proof film compartment and also had the advantage of a perfectly flat film plane, guaranteeing consistently focused images.

Although Contessa-Nettel had success in the 1920s, the entire German economy continued to suffer after World War I, causing a lot of instability in German industry. While the largest German companies were able to continue operations on their own, there was a growing number of smaller German companies that were struggling to stay in business. Contessa-Nettel AG was not immune to the struggles of the economy, and as a result in 1926 would partner with several other German camera makers like Erneman, Goerz, ICA, and Zeiss to form Zeiss Ikon AG.

While the idea of combining forces of several smaller companies into one larger company was probably a good way to stay in business, August Nagel found himself for the first time in his career to not be in charge of his own company. Prior to his partnership with Zeiss, he had free reign to design and release new models to his heart’s content, but now, he had to answer to a board of directors, all made up of executives from these other companies who didn’t always see eye to eye with Nagel’s vision.

In addition to his creative differences with the board, the other board members all had higher education backgrounds which Nagel lacked and he was often put down and ignored by his more educated peers. As a result, only 2 years after merging with Zeiss-Ikon, August Nagel would leave the company to form his own company, “Dr. August-Nagel-Fabrik für Feinmechanik”, or simply Nagel Werke.

Regarding his time working for Zeiss, it is said that Nagel kept a pretty big chip on his shoulder regarding his poor treatment while working for Zeiss. It’s this chip that is likely why he insisted on referring to himself as “Dr.” August Nagel, even though his doctorate was an honorary one bestowed upon him in 1918 by Freiburg University in recognition of his contributions to the German camera industry. It was common during interviews and speeches that Nagel would be brutally honest regarding his opinions of the board.

The rejuvenated Nagel was once again free to design his own models that were built to a very high standard and quickly earned him praise. Some of Nagel’s designs during this period were the Vollenda, Pupille, Librette, and Recomar. In the early 1930s, the German press reported on Nagel’s success saying “In spite of the economic misery of this period, Dr. August Nagel succeeded in bringing his new company to a high profile in a short time and to give world-class quality (sic) to his products. “

By the early 1930s, Nagel Werke had restored August Nagel’s reputation as a world class camera maker. With over 2 decades of experience making high quality and well performing models, he was highly respected all over the world. Despite his accolades and success at making quality cameras, the German economy was still poor and political changes were on the rise, both of which held back Nagel’s ability to continue to innovate.

Conveniently, around this time Kodak was looking to improve their reputation in the camera industry by offering a lineup of German designed cameras bearing the Kodak name. In 1931, representatives from Kodak offered to merge with Nagel Werke giving them the capital and support of one of the largest photographic companies in the world, with the understanding that August Nagel would remain as Managing Director and Chief Designer of the new Kodak / Nagel AG. Nagel would retain his title and stature from his own company while having the creative freedom to continue to develop and release his own models, while working for Kodak. It was a win win for both Kodak and Nagel. In December 1931, the merger was completed for an undisclosed amount of money, and with Nagel Werke’s merger into Kodak, came most of Nagel’s earlier models like the Pupille, Vollenda, and Recomar. Most of these models would be sold under the Kodak name, but would otherwise be unchanged.

After joining Kodak, Nagel would begin working on two new models, the Kodak Duo Six-20 which would be their first all new model designed to use the company’s new 620 film, and the Kodak Retina, which itself was based off the earlier Vollenda, would introduce the world to 135 format film, which would eventually become the most popular film standard ever made.

While working on these new models, most of Nagel’s earlier models would remain on sale until the late 1930s relatively unchanged other than being branded as Kodak, instead of Nagel cameras. For the models like the Vollenda being reviewed here, the collector’s value of an original non-Kodak, Nagel branded version is always higher. But despite any variance in collector’s price, the quality of the cameras was the same between the pre and post-Kodak days.

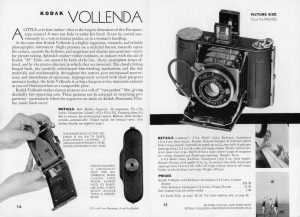

For the discerning photographer who demanded a high quality precision camera, German cameras were the ones to have, and to have one backed by the largest American photographic company was a win – win for many people. Cameras like the Vollenda represented a good bargain for someone wanting the precision of a German camera, but an American company to stand behind it. The image to the right from Kodak’s 1934 catalog lists the Vollenda with Radionar lens and Compur shutter for $33.50. When adjusted for inflation, that’s like $626 today. Certainly not pocket change, but a huge value compared to other high end cameras of the day.

Once war broke out in Germany, despite being owned by an American company, Kodak AG’s operations were interrupted and transitioned toward producing items for the German war effort, and all Nagel built cameras stopped production.

August Nagel would die on October 30, 1943. It is unclear if this had anything to do with the war itself, or if he passed away due to natural causes. In my research for this article, I found absolutely no evidence that Nagel was ill, or had any kind of declining health, so I have to imagine that whatever caused his death, was sudden.

Upon his death, control of Kodak AG would pass onto his son, Helmut Nagel, and it was perhaps the absence of the elder Nagel that when the Kodak AG factory would re-open in 1945, the decision was made to focus solely on 35mm cameras like the Retina. As a result, all roll film Nagel models from before the war like the Vollenda would be discontinued, never to be made again.

Today, anything associated with Dr. August Nagel is in high demand by collectors. There are those who will collect old Kodak cameras, those who collect old German cameras, and those who specifically seek out Nagel built models. As a result, these cameras usually fit the niche of most everyone who has an interest in this hobby, and as such usually causes their prices to escalate. It is not easy to find an old Vollenda like this at bargain prices, but it does still happen. These are wonderfully built and extremely capable cameras made in the glory days of camera making. If you ever have an opportunity to pick one of these up at anything closely resembling a good price, I absolutely recommend it!

My Thoughts

The Kodak Vollenda needs no introduction to camera collectors, so I’ll just cut straight to the chase and get to the point where I gush over this camera. I love pre-war German “nickel and leather” cameras, especially those made by Dr. August Nagel.

This Vollenda is the first prewar camera in my collection to use 127 film and I acquired it at a time when my interest in the format was higher than usual. 127, for those who don’t know, was the preferred format for “miniature” cameras before 35mm film became the standard. Even after Kodak’s release of their new 135 format of 35mm film, 127 still had the advantage of offering larger negatives (3cm x 4cm in half frame and 6cm x 4cm in full frame), and its more compact spool meant that 127 film cameras could be smaller than comparable 35mm cameras could. Of course, the biggest cons are in lack of convenience in loading and unloading, and the length of the film was quite a bit shorter, allowing for less images per roll. Still, there were enough people who preferred 127 film that Kodak still made it until 1995.

The compact size of 127 film cameras like the Vollenda is not always evident when looking at images on the Internet. The image to the left shows the Vollenda side by side with a Kodak Retina I. Notice that the height of the two cameras are close but the Vollenda is noticeably narrower. The camera is all metal, glass, and leather, yet still weighs only 342 grams. When folded, the camera very easily fits into a front jeans pocket or even a large shirt pocket.

Opening the camera requires pressing a release button on the top plate of the camera next to the uncoupled depth of field scale. The release button is in the exact location that a top plate shutter release would be if this camera had such a feature, which it doesn’t. The rest of the top plate is pretty sparse with only the winding key and flip up optical viewfinder present.

The Vollenda is a self-erecting design which means the lens and shutter should fully extend when the door opens, but on mine it needs a little assistance to open fully. I cannot be sure how these cameras would have functioned when new as it’s completely understandable for a nearly 80 year old camera to need a little bit of help opening. When it comes time to close the camera, a metal bar between the bottom of the lens and the door must be pressed to fold the camera shut. Do not attempt to force the camera closed without first pressing on this metal bar.

With the camera fully open, you are presented with a pretty standard looking Compur-Rapid shutter. The outer ring changes shutter speeds from 1 second to 1/500 and there is a little lever on the bottom that controls the iris of the lens. Thankfully both of these were in good working order when I first picked up the camera, but had they been sticky, a quick flush of naphtha oil would have quickly freed it up.

As with all Compur shutters of this vintage, there are two levers sticking out of the shutter at about the 10 o’clock position and the 8 o’clock position. The top one is the cocking lever and must be set prior to each photo. This camera has no type of double exposure prevention and it is not coupled to the film advance, so this must all be done manually.

The lower lever is the shutter release, which on this camera is partially blocked by the door. I found it quite awkward to have to stick my finger down in there to find the shutter release and push it inward towards the camera to fire the shutter. I felt as though this hampered my ability to hold the camera steady while shooting. When I look at all period advertisements for the Vollenda, all of the images show it with an optional, short shutter release cable screwed into the side of the shutter. Sadly, my example did not come with this type of cable release, but after fiddling with the built-in lever, I can clearly see that it would have been very useful. I won’t say the Vollenda is unusable without one, but this is one camera where the presence of an auxiliary shutter release cable is much appreciated.

The viewfinder is of a flip up optical design which I am a huge fan of. Many old cameras have very tiny viewfinders that are extremely difficult to see through, especially when wearing prescription glasses. The large and bright flip up viewfinders are incredibly easy to use due to their size, and as an added bonus have a sort of primitive diopter adjustment by moving the rear glass frame forward and back. The obvious downside to them however, is that they tend to be a bit fragile and I’ve seen more than a few of these old cameras with cracked or missing viewfinder glass. Thankfully, my example is in great shape.

The back of the camera has two red exposure windows which both must be used when transporting film. The backing paper for 127 film does not have the correct exposure numbers for “half frame” cameras like the Vollenda that shoot 3cm x 4cm images. You must use the exposure numbers for 4cm x 6cm exposures twice. When advancing the film, the first frame is shot with the number one in the red window on the right. For the second frame, advance the film until the number 1 is in the red window on the left. For the third frame, the number 2 must be in the window to the right, and so on. You have to remember to use every frame number twice. The 16th and final image is shot with the number 8 in the left red window.

To load film into the Vollenda, you must first slide the door latch on the camera’s left side. This opens the hinged back and you can see the film compartment. The takeup spool goes on the left, and a new spool of film goes on the right (supply) side. In the image to the left, I have an exposed roll of film on the takeup side of the camera. I would have removed this film and moved the empty supply spool from the right side to the left in preparation for the camera’s next roll. As with most Kodak cameras of the era, there is a beautifully designed logo on the film door reminding you to use only Kodak 127 in the yellow box!

The Kodak Vollenda was a popular camera that remained in production for several years after Nagel merged with Kodak. Although the exterior dimensions were slightly smaller than that of a Kodak Retina, it made larger exposures. The biggest con of course is being limited to 16 exposures per roll compared to the max of 36 with Retina’s 135 format. The high build quality, and larger exposures likely appealed to semi-professional photographers who wanted a pseudo-medium format camera, in a very compact size. I would guess that Vollendas were often used as travel cameras for photographers, or as backups to larger, more complex models.

The Vollenda, like all Nagel designed cameras is purposefully designed, beautiful to look at, and is capable of making excellent images. It’s hard to collect cameras and not lust after a something with Nagel’s name on it. I enjoyed handling the Vollenda, and it’s compact size meant that it would be tucked away into a pocket or small bag without taking up too much space. The Vollenda was a welcome addition to my collection and I anticipated that it would be a model I would come back to many times.

My Results

The biggest challenge of using a Vollenda today is the lack of 127 film. Sure there are a few niche emulsions like Rerapan 127 that you can still buy, but they are expensive, and in my opinion do not do a good job of taking advantage of the excellent optics on a camera like this. I prefer shooting color whenever I can, so these days, your only option is to either cut down larger film like 120 to 127 size, or buy expired film. I’ve gone with the latter method and sourced a few rolls of expired 127 color film from eBay. Kodak discontinued 127 in 1995, so thats about as “fresh” as you’ll find, and most 127 cameras had fallen out of popularity in the last 2 decades the film was still in production, so not much was sold. As a result, it can be difficult to find color 127 from the 1980s or 90s.

Still, I found some, and having quite a bit of experience with expired Kodacolor II from the 70s and 80s, I thought this Kodak Gold 200 from 1993 was basically brand new. I loaded up the camera right before Labor Day 2017 and made a mental note to shoot Sunny 16 with +2 stops of overexposure.

As it would turn out, shooting a moving parade was not the wisest choice I could have made for a first roll through an 80 year old scale focus camera. I generally do pretty good with guess focusing, but a combination of an awkward shutter release that likely added some body movements at the moment the shutter fired along with constantly moving subjects resulted in many of my shots coming out blurred. In addition, I was unable to mentally focus on the task at hand during the parade and I double-advanced the film twice, resulting in two blank frames. Sadly, of the 14 remaining exposures that I could have gotten from this roll, quite a few didn’t come out so well.

Adding further insult to injury, the 1990s Kodak film didn’t fare as well as I had hoped. I fully realized that this film wouldn’t shoot like fresh film, but considering the good results I got from Kodacolor II films from the 1970s and 80s, I expected more. The colors were muted as I had expected, but there were colored streaks that ran through the center of the film. These may have been caused by the two red windows, but I had used black electric tape over the windows during shooting, something I have done many times before without this problem.

Of the shots that I am sharing here, I feel as though I can still speak to the potential quality that I might have had with better film, and a more optimal shooting situation. The Radionar lens performed well. It was consistent with other triplets I’ve shot by Schneider, Wollensak, and Zeiss. Sharpness is excellent in the center, and only slightly tapers off near the edges. Vignetting is evident in nearly every image, especially near the corners that when combined with the pastel-like colors of the expired Kodak film, gave the images a really distinct vintage look that many modern digital photographers would use filters on their smartphones or computers to intentionally add.

Of the shots that I am sharing here, I feel as though I can still speak to the potential quality that I might have had with better film, and a more optimal shooting situation. The Radionar lens performed well. It was consistent with other triplets I’ve shot by Schneider, Wollensak, and Zeiss. Sharpness is excellent in the center, and only slightly tapers off near the edges. Vignetting is evident in nearly every image, especially near the corners that when combined with the pastel-like colors of the expired Kodak film, gave the images a really distinct vintage look that many modern digital photographers would use filters on their smartphones or computers to intentionally add.

It might seem like I was disappointed in my first roll through the Vollenda, and I guess I was, but I fault myself more than the camera for any shortcoming in these images. Aside from the inconvenient location of the shutter release, the shooting experience was enjoyable. I have a shutter release plunger from a Retina camera that should work with the threaded cable socket on the Compur shutter which I can use next time. I’ll either stick with black and white 127 film or see if I can convince a certain Quirky Guy to send me a new batch of fresh color film cut down to 127 size for any future rolls.

The Kodak / Nagel Vollenda is absolutely deserving of it’s reputation. This was a precision designed instrument built to the typically high German standards of the day. Assuming the camera has been taken care of in the near-century since it was made, most should be in good working order today, needing only a bit of cleaning to restore full functionality. Even with a basic 3-element lens, the camera is very capable. It is smaller than a Retina, but also produces larger exposures, and unlike other 127 cameras that might only give you 8 or 12 exposures per roll, the Vollenda gives you 16. Its such a shame that fresh 127 film is difficult to come by these days, but if you ever have an opportunity to own and shoot one, I highly recommend it!

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Kodak Vollenda was a compact camera designed in 1929 by Dr. August Nagel that was continued after he joined forces with Eastman Kodak in 1931. It is a precision camera built to the high standards of other German cameras of the era. Despite being smaller than a Kodak Retina, it produces larger exposures using 127 film. My only complaint about shooting the camera was the awkward location of the shutter release, which can be easily remedied with a short shutter release cable. The Schneider Radionar lens produces sharp images with some vignetting at the corners, giving a very distinct vintage look. Finding fresh 127 film can be a challenge these days, but if there ever was a 127 film camera that was worth finding film for, this is it. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.8 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Vollenda_48

http://elekm.net/pages/cameras/spotlight_vollenda.htm

http://www.ukcamera.com/classic_cameras/nagel3.htm

http://www.historiccamera.com/cgi-bin/librarium/pm.cgi?action=display&login=vollenda

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-4713-Nagel_Vollenda%2048.html

Thank you for this comprehensive article! I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again 🙂 Yay 127!

That Quirky Guy will get the 127 color factory up and running again at some point!

Great write up of both a legendary brand, and a now too easily overlooked aspect of their fine lineup. This camera really does seem to do well, even with the 20 year old film you put in it, so I am quite curious what a modern emulsion would do when inside of this great camera!

The Kodak Retinette model 147 (the first of this series, dating to the late 1930s) had a bottom-hinged lens door, same as your Vollenda. To my knowledge, it is the only model Retinette or Retina to have such a door; all subsequent models were side-hinged.

I think you’re right. Looking through Chris Sherlock’s Retina site, the 147 seems to be the only bottom hinged camera in that series.

Thank you for a most informative and enjoyable read

I am glad you enjoyed it, Graham!

Nice review of a pretty obscure camera. You have been pretty hard on yourself regarding the photos. Yes. It is hard to shoot these old scale focus cameras. However, I have to put the quality of the photos- above and beyond focus considerations- among the best, in overall rendering, of the many photos you have presented on this page. I really like the overall texture and color rendition of the shots. Some seem just a bit underexposed, but that is likely the result of shutter speeds that are not all that accurate. Thanks again.