This is a Lordomat C35, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Leidolf Wetzlar in Wetzlar, West Germany starting in 1956. The Lordomat C35 is a variant of the original Lordomat from 1954, adding an uncoupled selenium exposure meter with exposure calculator and a separate auxiliary viewfinder for 35mm, 90mm, and 135mm lenses. Like the original camera, the Lordomat C35 used a unique breech lock interchangeable lens mount and had a variety of lenses made for it. Leidolf was located in the same city as Leitz, who produced the Leica camera, and employed many former Leitz employees, although apart from using the same kind of film and having interchangeable lenses, very little is shared with the Lordomat’s neighbor camera.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

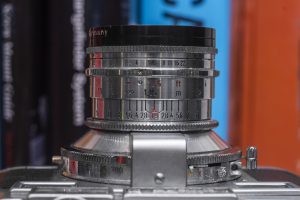

Lens: 50mm f/1.9 Leidolf Wetzlar Lordon coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Lordomat Breech Lock Screw Mount

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder and Second Viewfinder with 35/90/135 Frame Lines

Shutter: Prontor-SVS Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium Cell

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, Multiple Viewfinders, Exposure Calculator

Weight: 713 grams (w/ 50mm f/1.9 lens), 558 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/lordomat_c35.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Lordomat C35 was an update to the original model, adding an uncoupled selenium exposure meter and an auxiliary “universal” finder for the optional 35mm, 90mm, and 135mm lenses made for the camera. A new 50mm f/1.9 Lordon lens also became available at the same time as this camera for an additional charge. In the end, only the f/1.9 lens adds anything meaningful to the system, but the changes to the C35 take nothing away from the excellence of the original model. If you already have a regular Lordomat, I do not think it’s worth upgrading to this model, but if this is your first Lordomat, you’re in for a treat as it’s a special camera! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.7 | ||||||

History

In the history of the optics industry, there is no shortage of examples where employees of one company worked for another. Franke & Heidecke, makers of the Rolleiflex was founded by ex Voigtländer employees, Nicca, makers of Japanese rangefinders, who also merged with Yashica, was founded by an ex Seiki Kogaku (Canon) employee, and August Nagel formed his own company, who was absorbed into Zess-Ikon, then left to form Nagel Kamerawerke, who was in turn bought out by Kodak to form Kodak AG are just three of many examples.

In the history of the optics industry, there is no shortage of examples where employees of one company worked for another. Franke & Heidecke, makers of the Rolleiflex was founded by ex Voigtländer employees, Nicca, makers of Japanese rangefinders, who also merged with Yashica, was founded by an ex Seiki Kogaku (Canon) employee, and August Nagel formed his own company, who was absorbed into Zess-Ikon, then left to form Nagel Kamerawerke, who was in turn bought out by Kodak to form Kodak AG are just three of many examples.

Note: A large part of my research into the history of Leidolf and the Lordomat comes from issue 15 of a German language magazine called Photographica Cabinett that devoted an entire issue to Leidolf in December 1998.

The entire 20 page issue is written in German, and although I do not read German, using Google Translate, I was able to translate most of what is covered. If you read German and would like to see the original issue, see the link above.

In the mid 20th century, Leifolf Wetzlar was a maker of fine German cameras, but before that, they made microscope parts. The company was formed by Rudolf Leidolf in 1921 at the age only 23. Leidolf was born on October 15, 1898 and was the oldest of six children who worked at his family mill in the Ulmbach Valley in Germany.

In his early years, Leidolf would leave the family business to become a precision mechanic working for Hensoldt & Söhne in Wetzlar. While working there, he would develop and interest in microscopy, which led him to forming Leidolf & Regel OHG in a small rented workshop in Wetzlarer Hintergasse.

In the 1920s, and 1930s along with his wife Magdalene and partner, Karl Regel, Leidolf produced optics for local companies including Leitz. With less than 10 employees, Leidolf’s early output was slow, but in 1927, the company would relocate to a much larger workshop on Garbenheimer Strasse.

In 1937, Leifolf and Regel would part ways, and the company’s name would change to Optisch-Mechanische Werkstiitte Rudolf Leidolf. At this time, the company expanded it’s product offerings to “prism glasses” and light weight binoculars.

Leidolf would stay in business during World War II, despite repeated attempts to join the Nazi party. Still producing glasses and binoculars, Leidolf’s production would slow to a crawl due to a combination of lack of raw materials, but also that many of the men in the factory went to serve in the military, leaving few skilled laborers behind.

Fortunately, Leidolf’s factory received minimal damage in the war, as Allied bombing raids largely avoided the region, so production was quickly able to resume after the war. Fate wasn’t as kind to other German optics companies though as many suffered major damage and for the first couple of years after the war, there was a shortage of availability to produce them. Sensing an opportunity to use their expertise, Rudolf Leidolf’s son-in-law Fritz Meinhardt suggested the company start producing cameras.

Fritz Meinhardt was born in 1913 in Hartenrod, Germany as the second child of four. Growing up, Meinhardt was a terrific athlete and was skilled at playing the piano. As he got older, Fritz Meinhardt showed a strong interest in being a musician, but hardship that fell upon his family forced him to change careers.

In 1927 at the age of only 14 years old, Meinhardt would become employed at Leitz in Wetzlar as a precision mechanic. Meinhardt’s excellent dexterity which likely benefitted him playing the piano, allowed him to excel in his new job and he allowed him to be assigned larger and more significant projects. At the age of 25, he developed a hydraulically controlled milling machine for binocular housings, which was groundbreaking at the time. This drew the attention of company president, Enst Leitz Jr, who would encourage and support him in his development at the company.

Fritz Meinhardt was making a name for himself at Leitz and had a bright career ahead of him at the company, but in 1938, he would meet Rudolf Leidolf’s 16 year old daughter Hiltrud and they would become romantically involved.

Learning of his daughter’s new boyfriend’s role at Leitz, Rudolf and Fritz shared a similar interest in precision mechanics. Over time, Fritz would advise Leidolf in ways he could improve efficiency at his factory, offering friendly advice, but after the young couple’s wedding, Fritz Meinhardt would leave his job at Leitz and come to work for Leidolf where he would lead the company in it’s new direction building cameras.

Now working for Leidolf, in 1948 Fritz Meinhardt began working on a new camera prototype called the Mioflex. The Mioflex had a boxy body with what looks to be a prewar leaf shutter, and some type of coupled rangefinder. The camera later evolved into the Mikroflex which replaced the shutter with a postwar Prontor, while keeping the Zeiss Tenax II style rangefinder. Neither camera would ever make it into production, however.

Leidolf’s first camera to be produced was the Leidax in 1949. The Leidax shared the same shutter and boxy body from both the Mioflex and Mikroflex prototypes, but eliminated the rangefinder, replacing it with a simple optical viewfinder. The camera shot 4cm x 4cm images on 127 roll film. Shortly after the Leidax’s release, the camera was renamed the Leidox as it was thought the name was too close to “Leica”.

Two versions of the Leidox were produced, an early one with a Vario shutter and a later version with a Prontor. Shortly after it’s release a very similar camera that used 35mm film called the Lordox was also produced. Leidolf’s first cameras were not very aspirational, but Fritz Meinhardt was a quick learner and soon the company would start building much more advanced models.

In 1953, Leidolf would debut a new camera at Photokina called the Lordomat. The Lordomat was a much more advanced camera than Leidolf’s earlier offerings. Featuring a new breech lock interchangeable lens mount, a combined coincident image rangefinder, and an all new body, the Lordomat was a tremendous value at it’s original price of 240 DM.

The Lordomat would be received positively, no doubt seen as a competitor to the Leica which was produced in the same down, but selling for a fraction of the price, many people saw Lordomats as a cost effective alternative. Despite increased demand, the company would only expand to around 100 employees, producing only 1000 cameras per month.

The company’s small size meant that they had no skill at marketing or distribution, so for that, Leidolf relied on third parties. In Germany, Wedena of Bad Nauheim did all the retail sales of Lordomats, with other third parties in other areas of the world. The Lordomat was successful in other areas of Europe and the United States where an estimated 50% of total production was sold.

In the previous ad to the left from 1955 lists the price with a Lordonar 5cm f/2.8 lens for only $89.50, and a leather ever ready case for $9.95 extra. These prices, when adjusted for inflation, compare to about $930 and $100 today.

In 1956, with the Lordomat selling well, Fritz Meinhardt would design an updated model called the Lordomat C35.

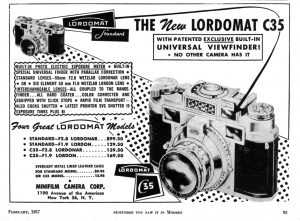

The new model, featuring a similar body and interchangeable lens mount as the original model, added an uncoupled selenium exposure meter, a built in secondary viewfinder with frame lines for 35mm, 90mm, and 135mm lenses, along with the availability of a new 6-element Lordon 50mm f/1.9 lens. Although the lens mount on the C35 was the same as the original model, it’s added viewfinder made the use of the other lenses designed for it more practical. In addition to the two 50mm lenses, also available were a 35mm f/3.5 Travenor, a 90mm f/4 Travenor, and a 135mm f/4 Travenor. Although all of the lenses were designed by Leidolf, their construction was outsourced to other companies such as Enna and Schacht.

The Lordomat C35 would sell alongside the original model, now called the Lordomat Standard, at a cost of $139.50 with the original f/2.8 Lordonar or $169.50 with the new f/1.9 Lordon. Once again with inflation, these prices compare to $1450 and $1760 today. Although these prices wouldn’t have been seen as pocket change, they were a far cry from the cost of the Leica M3, which by the mid 1950s was Leitz’s flagship camera.

Leidolf’s reliance on outside sources to handle all retail and distribution allowed them to operate a more streamlined business in the early days as the company could focus entirely on the development of new cameras, but this would prove to be the company’s undoing in the next decade.

Despite looking different and sharing very little in common with the design of the Leica, the company’s location in Wetzlar resulted them being continually compared to the Leica, with the common label of a “poor man’s Leica” unfairly affixed to the company’s product.

By 1957, a large amount of Leidolf’s distribution was being handled by Foto-Quelle, who was a large mail-order and retail distributor of photographic goods in Europe. The company’s Revue line of cameras was very popular, and consisted of many different rebadged German, Japanese, and Soviet cameras that were sold all over the world. No matter how successful Leidolf had become, they were still a very small company and began to suffer demands for cost cutting and lower cost models by Quelle.

Fritz Meinhardt initially refused to cut corners with production of the Lordomat, but with the threat of being dropped from their distributor, produced some lower cost variants like the Lordox Baby and the Lordox Junior which removed the interchangeable lens mount and rangefinder. A version of the Lordox Junior, but with an interchangeable lens mount was sold by the US department store chain, Montgomery Ward as the Adams 351.

Despite increasing pressure from Quelle to continually offer cheaper models, Fritz Meinhardt would continue evolving the Lordomat line, releasing new models like the Lordomat SE and SLE, the Lordomatic, and the auto exposure Lordox Super Automatic. At least 20 different models of Leidolf cameras were produced in this period, and rather than list them all, I highly recommend checking out Cees-Jan de Hoog’s excellent Leidolf page showing many of the different models.

Sadly, by 1962, with the increase of competition from the Japanese camera market and Leidolf’s reluctance to go down market, Foto-Quelle would drop Leidolf, cancelling all open orders, and leaving them without anyone to buy their cameras. What few sales they had the US and other markets were not enough to keep the company alive and the company would go out of business.

After Leidolf’s closure in 1962, many of its assets were bought out by the Swiss company Wild Heerbrugg, another optics company specializing in surveying instruments, microscopes and instruments for photogrammetry. In a strange twist of fate, in 1987, Wild Heerbrugg would merge with Ernst Leitz GmbH of Wetzlar. The combined company continued to make optical instruments, and then in 1990 became fully owned by the Leica Holding Company. The brand name “Wild Heerbrugg” is still in use today in several of the company’s products.

Today, the entire Lordomat series is sought after by collectors, both for it’s good looks, quality design, but also that people are curious about Wetzlar’s “other” camera maker. I do not think it is fair to compare anything Leitz made with a Leidolf product, and using the name “poor man’s Leica” is a disservice to this camera. The Lordomat and Lordomat C35 are entirely different cameras that other than shooting the same type of film, and being made in the same city, share nothing in common.

The Lordomat C35 is a really cool camera, and one that is a heck of a lot to shoot. In my time collecting cameras, I’ve come across a number of Lordomat cameras and know many other collectors with at least one, and more times than not, other than a little stiffness or perhaps a misaligned rangefinder, most still work today.

My Thoughts

After reviewing the original Lordomat in November 2015, it quickly became one of my favorites. I picked it up a number of times in the years that would follow for additional rolls of film and I had always meant to go back and revisit that review.

As things happen though, I never did anything with my Lordomat review, until I found this Lordomat C35 at a local store for a very reasonable price. It came in a leather carrying case, which when I opened it up, found the 35mm Schacht-Travenar lens I use in this review. Score, I thought to myself and picked it up, thinking that rather than updating my original Lordomat review, I would just type up something new for this camera.

Comparing the Lordomat C35 to the original model, the C35 is the same camera with a larger top plate containing the uncoupled meter and auxiliary viewfinder. This gives the camera more height and more weight, but depth front to back and width are identical. Without a lens the Lordomat C35 is understandably heavier at 558 grams compared to 486 grams for the original. Build quality seems exactly the same as do the ergonomics of controls, rangefinder, lens mount, shutter, and lenses.

Up top, the Lordomat C35 differs from the original model in that the selenium meter readout and exposure calculator are here. The meter on the C35 is uncoupled to the camera, which means changes to the shutter speed and f/stop have no impact on the reading of the meter. In order to use it, you must first turn the outer ring to calibrate the film speed from ASA 6 to 1000 (DIN 9 to 31) and then point the camera at whatever you want to take a reading of. The needle will be pointing at a zebra stripe which corresponds to a specific shutter speed. You will then turn the inner ring to point a diamond shaped pointer to whatever shutter speed the needle is indicating and then any combination of shutter speeds and f/stops must be manually selected on the front of the lens for proper exposure. It sounds a bit more complicated writing it out than it is in person, and was consistent with how other uncoupled metered cameras of the era worked, but it’s certainly not elegant.

To the left of the meter is the accessory shoe and a small dial with distance markings on the leading edge of the top plate. This dial is a parallax corrector for the 90mm and 135mm frame lines in the auxiliary viewfinder (the 35mm view is not affected). Turning it tilts the image downward to compensate for the distance between the viewfinder window and lens at close distances.

The rest of the top of the camera is the same as the regular Lordomat, with the rewind knob and film reminder dial on the left, and the exposure counter, reset dial for the exposure counter, and stubby double stroke film advance lever on the right. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have already been made, and must be manually reset after loading in each new roll of film. The film advance lever operates front to back, which is opposite of most film advance levers and requires two strokes for each exposure, which might seem odd to the first time user.

Flip the camera over and on it’s bottom is a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket and the circular door release for the film compartment. Turn the dial so that a black dot points to the letter “O” for open, and “C” for closed.

The back of the camera is much like the original model, but has two viewfinder eyepieces instead of one. The upward location of the auxiliary viewfinder is at an angle, which is slightly less elegant than of a screw mount Leica or Argus C3, but isn’t that hard to use. Also on the back of the top plate is the engraved serial number with C35 prefix. This is the only place on the camera where the label C35 exists.

From the side of the camera, you get a good look at the L-shaped cover over the rangefinder coupling above the shutter. The shutter speed ring goes through this cover, so you can grip it from either side. Also notice the forward angle facing strap lugs on the camera. This position allows the Lordomat C35 to hang from a neck strap without tilting forward from the weight of the lens.

With the back of the camera off, we see a fairly ordinary 35mm film compartment. Loading in a new cassette of film is very easy and does not require you to lift up on the rewind knob to clear the fork. Film travels from left to right onto a single slotted and non-removable metal take up spool. When winding the camera, the spool rotates clockwise, which means the exposed film wraps around it opposite of how it was in the cassette. This is thought to help maintain flatness while the film transports through the camera.

On the inside of the door is a polished metal film pressure plate. A small metal nub sticks out and maintains pressure on the film cassette to keep it from moving while loaded in the camera. A small but nice design element of the camera is that the 1/4″ tripod socket on the bottom of the camera is part of the main camera chassis. This is superior to other cameras where the tripod socket is part of the bottom plate, as the metal chassis is much stronger and would support the camera without wiggling. The Lorodmat C35 has very deep door channels and predates the use of foam light seals, so no light seal replacement is necessary with this camera. As long as the camera hasn’t been physically damaged, you should have no problems with light leaks.

Up front, the shutter and lens controls are all visible from the top, like most other leaf shutter 35mm cameras. On the f/1.9 Lordon, along with the other two Lordomat lenses in my collection, the aperture control is always farthest from the body. The Lordon has positive click stops at every indicated stop and a very smooth focus. The full motion from minimum to infinity focus requires an almost full 360 rotation of the lens, which is great for precision, but not so much for speed. It is difficult to go from near to far focus in one twist of the wrist.

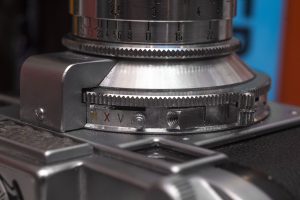

Shutter speeds are controlled with the knurled ring around the shutter. This ring passes through an L-shaped rangefinder coupling cover, so the available speeds are indicated off to the left. Despite the offset location of the shutter speed numbers, you can grip the shutter speed ring at any position around the shutter. Opposite the shutter speeds is a small slider for M and X flash sync and a V position for the self-timer. As with any half century old camera with a mechanical self-timer, you should avoid trying to use it, unless you are certain the camera has had a recent CLA.

To the right of the MXV lever, is a threaded socket for a cable release, and below that a T-shaped handle for the shutter release. The location of the shutter release isn’t perfect as your right index finger needs to be a bit lower than other cameras with similar front shutter releases, but it’s certainly not uncomfortable and only takes a short while to get used to.

The Lordomat’s lens mount is a breech lock screw type, very similar to Canon’s FL/FD mount in which a locking ring around the shutter rotates to release the lock and then the lens lifts off the body. Unlike the Canon however, the Lordomat’s locking ring must be fully rotated a couple of times before you can separate the lens. You do not need to rotate the lens at any point when mounting or dismounting the lens, as only the lock rings needs to be turned. With then lens off the camera, when it is time to put it back on, you must align a small pin on the lens to an index notch near the 11 o’clock position around the locking ring’s screw threads before attempting to secure it.

For someone not familiar with the Lordomat, it’s likely that they wouldn’t know this had an interchangeable lens mount as the locking ring looks very similar to the focus and aperture rings. It’s location nearest the body looks is unsuspecting and could easily be missed, but once you know how to use it, it is not difficult.

With either of the 50mm lenses mounted to the camera, you use the main viewfinder for both composition and rangefinder focus. With any of the auxiliary lenses, you still use the main viewfinder for the rangefinder, but then move your eye to the auxiliary viewfinder to see a slightly purple tinted image for the entire 35mm wide angle lens. Projected frame lines for 90mm and 135mm lenses are in the middle.

While I appreciated the economy of having two viewfinders representing all four focal lengths offered in the Lordomat system, the auxiliary viewfinder is small and isn’t very useful. With prescription glasses, I could not see the entire 35mm frame. The 90mm and 135mm frame lines are even smaller, and while I didn’t have lenses with either of those focal lengths, if I did, I would have much preferred a dedicated clip on viewfinder.

The Lordomat C35, much like the regular Lordomat is a very nicely designed camera that looks great, has a compact and easy to use body, and feels great in your hands. I don’t know that the addition of an uncoupled selenium meter and the tiny auxiliary viewfinder make it any better than the original Lordomat, but they certainly don’t make it worse. The ergonomics of the camera are good, and although it lacks the top speeds of other German cameras of the era, was likely good enough for the vast majority of people who would have bought it.

My Results

Having had good luck in my previous experiences with the Lordomat, for the C35 I shot two separate rolls of film, a slightly expired roll of Fuji 200 early last spring, and then a fresh roll of Kodak ColorPlus 200 this summer, partially covering a trip I took to visit Washington DC and Philadelphia. For these two rolls, I used a combination of the 50mm f/1.9 Lordon and the 35mm f/3.5 Schacht-Travenar. Although the selenium exposure meter on this camera responded to light and appeared to be accurate, I did not rely on it, instead using my best Sunny 16 estimates.

A quick note about the gallery above is that there are a few images such as the red building which show extreme vignetting near the corners. This is a result of a boneheaded move where I was using the wide angle 35mm Schacht lens and a lens hood which wasn’t made for it. That particular lens hood works fine at 50mm, but becomes visible in the corners with anything wider and I did not realize it until after I was half way through the roll. A majority of the wide angle and all of the 50mm images don’t have this vignetting. I included a couple of those images anyway as they still show incredible sharpness in the corners and how well the lens renders, but also as a cautionary tale to not use hoods on wide angle lenses, unless they are specifically made for it!

Hood issues aside, the images I got from both rolls of film using both lenses was outstanding across the board. Earlier in this review I stated that the Lordomat shares nothing in common with a Leica other than using the same type of film, but I’ll revise that to say both are excellent platforms for making really nice images. I lack the testing methods or the vocabulary to accurately compare the optical characteristics of these images compared to other German brand lenses, but I will say that to my eyes, these look as good as any other 35mm camera system I’ve shot.

I’ve often voiced my preference for wide angle lenses over standard and that really shows here as the images where I could fit more into the shot are also the more interesting ones in the gallery above. The two of the US Treasury building, the little girl riding the seesaw, and the bathtub planter are much more interesting to me than had I made those same shots with the 50mm Lordon.

Sharpness is excellent across the frame with little to no (natural) vignetting is evident. There’s a bit of curvature at the edges which might not be there in a more professional wide angle lens, but it’s hardly anything that bothered me.

Using the Lordomat C35 is much like the regular Lordomat as everything below the meter and auxiliary viewfinder is exactly the same. The body is almost identical in width and thickness to a Barnack Leica, and the weight is on par for a camera this size. Ergonomics of the front shutter release and wind lever are excellent. For the first time user, the positioning of the stubby double stroke film advance lever might be a little strange, but it’s something you get used to quickly.

If I had one complaint about the Lordomat C35, its that I don’t think the features added to the C35 make it a meaningfully better camera than the original Lordomat, at least not today. The auxiliary viewfinder gets the job done, but is just as small as the main viewfinder. If I were to shoot the 35mm wide angle Travenar on the original Lordomat, I think I would have preferred a much larger auxiliary 35mm viewfinder clipped to the accessory shoe.

And while the meter did work on my example, I have to imagine that in the 1950s when this camera was made, many people already had handheld meters or at least were good enough at Sunny 16 so as not to need it. The meter is uncoupled which means that it’s reading is not affected by changing shutter speeds or f/stops, so it certainly doesn’t speed exposure metering up.

Make no mistake, the Lordomat C35 is a great camera, is a lot of fun to use, and makes excellent photos, I just don’t see it’s added features as worthy of an upgrade to the original. The C35 both operates and looks like a regular Lordomat with two additional features grafted onto the top.

If you’ve never owned a Lordomat camera of any kind however, and you have the opportunity to buy a C35, by all means buy it! For as little of a benefit that I feel the added features are, they certainly don’t take anything away from the camera’s operation. Fritz Meinhardt designed one heck of a camera that looks great, works great, and based on my small sample size, holds up well to over half a century of time. If you find a Lordomat of any kind for anything close to a price you can afford, run, don’t walk to the cash register and buy it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://sites.google.com/site/harrissonphotographica/home/leidolf-cameras

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/at-last-the-lordomat-c35.501471/

https://www.rangefinderforum.com/node/138671#post3179516

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/leidolf/leidolf.html

https://wesloderandnikon.blogspot.com/2022/01/the-lordomat-standard-primus.html

You might note that the parallax correction dial only affects the 90 and 135 frame lines. The 35 finder is unaffected. Also, you might mention my review of the Lordomat standard on my blog. http://wesloderandnikon.blogspot.com/2022/01/the-lordomat-standard-primus.html. I use my middle finder for the shutter release. More stable that way. But how do you make sure that the takeup spool is actually engaging the film? Does not seem too secure to me. I always find myself checking the rewind to make sure it’s turning before I am satisfied that the film is advancing as it should. An excellent and fair review. I enjoy my Lordomats. Good picture takers.

Thanks for the comment, Wes, and good point about the parallax correction. I’ll update it to say that and include a link to your review in the Links section at the bottom.

Montgomery Ward sold a private-label version of the basic Lordomat under the name “Adams 352”. It had a black plate across its upper front, akin to the Lordox Junior. I no longer have this camera, but recall that it had a Trioplan f2.8 lens.