This is a Mamiya Auto XTL, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by Mamiya Optical Co., Ltd. starting in 1971. It was the first in Mamiya’s short lived X-series and upon it’s release in April 1971, was the most advanced 35mm SLR camera in the world. It incorporated a large number of design elements and features that were not yet common in competing cameras. The camera was very ambitious, too ambitious though, and it sold poorly. It was too complicated and advanced for the average amateur and had too much unproven technology for pros. It spawned a later variant called the Auto X-1000 in 1975, but quickly faded from the marketplace.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 55mm f/1.8 Auto Mamiya/Sekor ES coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Mamiya Bayonet ES-mount

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Prism with Full Information Readout

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: CdS Focal Plane Meter with Shutter Priority AE

Battery: 1.5v Silver Oxide S76 / SR44 / 357

Flash Mount: Flash Hotshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 720 grams (body only) / 989 grams (with lens)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/mamiya_pdf/mamiya_auto_xtl.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Mamiya Auto XTL was Mamiya’s first attempt at a serious professional 35mm SLR. When it arrived on the market, it was the most feature rich model on the market. Featuring an all new bayonet lens mount, shutter priority auto exposure, a 6% spot and averaging CdS exposure meter that took a reading from the film plane, exposure hold, the most comprehensive viewfinder of any camera on the market, and a large number of ergonomic improvements such as a flared focus grip, over sized shutter speed selector, and film advance lever, all for easy handling. The Auto XTL had a large variety of excellent lenses and accessories available for it, making it appealing to professional and advanced amateur photographers. The camera had every feature someone might have wanted in the early 70s, but apparently that was not enough as it sold poorly, and would be discontinued 4 years after it’s release, leading Mamiya down a financial path to bankruptcy. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.6 | ||||||

The first words that come to mind when I think of the Mamiya Auto XTL are ones that I feel like I’ve said recently and they are “Another SLR, another lens mount.”

And I did just say those words in my recent review of the Rolleiflex SL35 which used a proprietary QBM bayonet mount which was only used on that one camera and it’s variants.

Like that Rollei, the Mamiya Auto XTL introduced another proprietary bayonet mount that is unofficially called the Mamiya ES mount. It was only used on this camera and its successor, the Mamiya Auto X1000 from 1975.

Prior to the XTL, Mamiya manufactured 35mm SLR cameras primarily using the M42 screw mount, but also had a few using the Exakta mount, and in the case of the Nikkorex F which they produced for Nippon Kogaku, the Nikon F-mount.

Mamiya was no stranger to 35mm cameras, making a number of rangefinder, fixed lens SLR, and scale focus cameras in the 1950s and 60s, but they saw the greatest success with their professional lineup of medium format Twin Lens Reflex cameras. Mamiya’s C-series were large and heavy twin lens cameras that had a bellows focus system that allowed them to get much closer than traditional moving standard TLRs. They also had an interchangeable lens board allowing a user to switch between a wide angle or telephoto lens using the same camera body, even with film loaded.

It would seem that Mamiya liked to have their hand in a large number of camera markets, which possibly worked to their detriment as it diluted their market presence in everything but the professional TLR segment. It seemed that for the non professional, everything else Mamiya offered was good, but not great.

So it was with a bit of curiosity that in the early 1970s, the company decided to finally enter into the advanced amateur market with an all new SLR. Although Mamiya had been making SLRs since the late 1950s, they were late to the game with innovation. Relying on Exakta and screw mounts, most of Mamiya’s early offerings followed someone else’s lead.

The Auto XTL was an ambitious camera that Mamiya added many state of the art features such as a switchable 6% spot/averaging meter that took readings at the film plane, an exposure hold switch, shutter priority automatic exposure, and the most information filled viewfinder of any camera at the time. The idea of taking a light reading at the film plane was first available in the fixed-mirror Canon Pellix, but also in the very successful Olympus OM-2 from 1975, four years after the release of the Auto XTL. Taking a reading exactly where light meets the film is more accurate as slight variances in light traveling through a prism and the possibility of stray light entering through the rear viewfinder can negatively affect the reading in traditional SLRs.

Mamiya consulted focus groups to find which features were valued by photographers and which weren’t. In an effort to make the controls easy to use, things like the focus ring were flared at the end for an enhanced grip, and other controls like the shutter speed dial and wind lever were over sized.

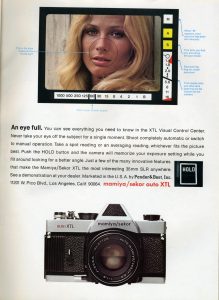

Upon it’s release in 1971, magazine reviewers claimed it the camera that has everything for everyone. It’s large set of features were seen as cutting edge and innovative. Here are two period advertisements for the Mamiya Auto XTL, the first from Modern Photography’s 1972 Buyer’s Guide, and the second from the May 1971 issue of Camera 35 magazine.

The Auto XTL’s innovative and long list of features also increased it’s price. In 1971, list prices with f/1.8 and f/1.4 lenses were $319.50 and $349.50 respectively (comparable to about $2000 and $2200 today), these cameras were not cheap. They were both too expensive for casual photographers and too risky for the pros.

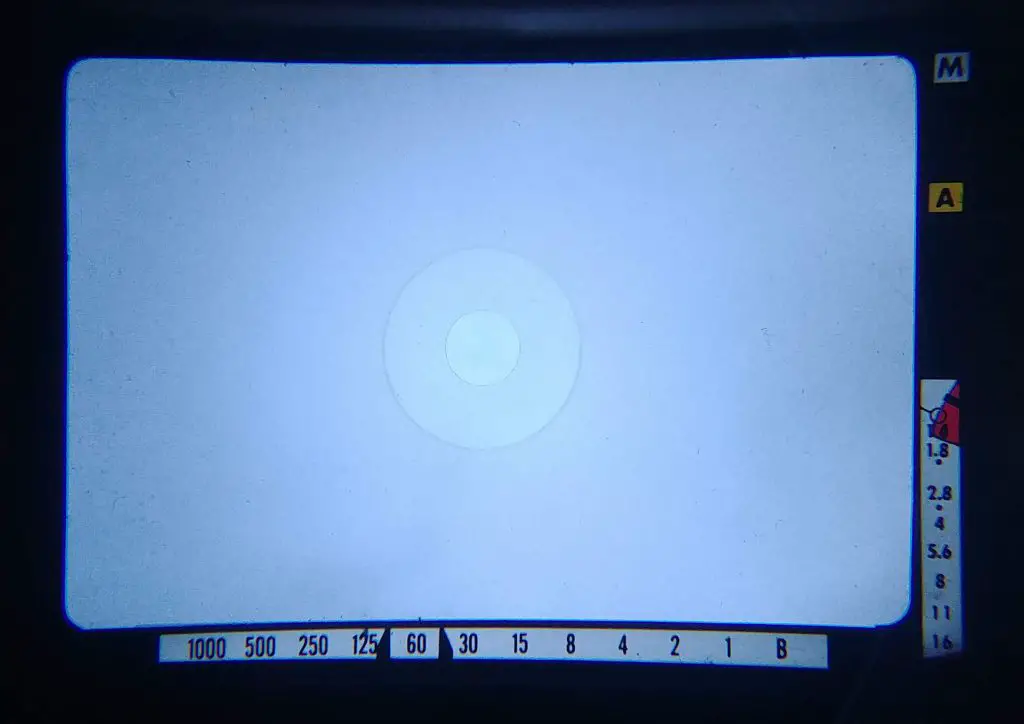

Another factor working against Mamiya was that although the camera worked well, many of the advanced features required compromises that people weren’t used to dealing with at the time. The large amount of information in the viewfinder makes for a cluttered view, and the lack of any sort of backlighting rendered this information useless in poor lighting.

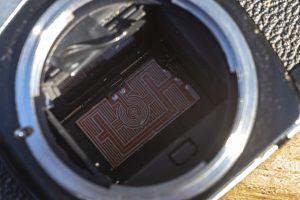

The focal plane exposure meter required the use of a semi transparent reflex mirror that allowed 30% of light to pass though, only reflecting 70% of the light into the prism, making for a darker viewfinder. This isn’t much of an issue with fast lenses like the 55mm f/1.8 and f/1.4 lenses, but the viewfinder can get quite dark and using slower wide angle and telephoto lenses.

Edit 2/5/2021: After publishing this review, I found this short review of the Mamiya Auto XTL in Herbert Keppler’s “On the SLR” column from February 1971.

From a feature perspective, the Mamiya Auto XTL was a very capable camera that should have allowed for it to be a success with professional and advanced amateur photographers. Mamiya themselves certainly had the respect of the pros with their excellent medium format cameras at the time, but somehow, they missed the mark with this camera and it sold poorly. It is plausible that the pros were turned off by so much technology. Professional photographers need to depend on their cameras to make a living, so many will generally prefer a more robust, but less featured camera for their work. This explains why Nippon Kogaku often held back new features like Auto Exposure and electronic shutters before offering them in their pro-level F-series. Models like the Nikon FE and FA had features before the F3 and F4 did, so maybe the target audience Mamiya was aiming for decided to take a “wait and see” approach.

Whatever the reason, the Auto XTL would be superseded by a single model, the Mamiya Auto X1000 in 1975. This model was the end of the line for the X-series as it was only available for a single year before being discontinued. Mamiya would go through a period of financial struggle in the late 70s and early 80s and eventually enter bankruptcy in 1984.

Today, the Auto XTL is a bit of an unknown camera in the collector’s world. Photographers active in the early to mid 1970s probably remember them, but the lack of information on them online suggests that it’s a mostly forgotten model. There are a few out there who recognize them as a very innovative and pioneering camera, but otherwise seem to get grouped film Mamiya’s long history of unremarkable 35mm SLRs. When collectors think of a Mamiya camera, models like the M645, RB67, or their C-series TLRs are usually the first to come to mind, not the Auto XTL. These cameras rarely come up for sale, but when they do, prices are rather hard to predict due to such a sample size.

My Thoughts

I learned of the Mamiya Auto XTL early on in my days as a collector, but a quick search turned up very few for sale and I quickly forgot about it. It wouldn’t be until a few years had passed where I stumbled upon a mention of one on the many photography related blogs I read and I thought it would be worth looking into picking up again.

These things don’t show up for sale often, but when they do, asking prices are quite high. Sellers who search for them likely find the same few sites that all state the same thing about how advanced the camera was when it debuted and how rare it is, and then instantly see dollar signs.

While it’s true that the Mamiya Auto XTL was pretty advanced when it first debuted, it was only advanced because it had a combination of features that weren’t common until a couple of years later. There is nothing the Auto XTL can do that later cameras couldn’t, and in some cases, did better. Had you known no chronology of when this model was released, you’d likely assume this was just another run of mill auto exposure SLR from the mid 70s.

In a nutshell, the only thing truly special today about this camera is that it was an ambitious model made by a company not known for ambitious 35mm SLRs, with a lens mount that no other camera used, and had a combination of features that for a very short period of time was cutting-edge.

Now that I had a Mamiya Auto XTL in my possession, would it hold up to expectations that an innovative camera might give? After all, this was state of the art stuff, so maybe Mamiya did something better than everyone else who had similar cameras in the early to mid 70s. I’ll start with the good.

The Mamiya Auto XTL is an attractive camera with subtle design cues that differentiate it from the massive number of 35mm SLRs coming out of Japan at the time. The leatherette strip on top of the pentaprism is a nice touch and gives the camera a premium look. The Auto XTL was the last Mamiya camera to be labeled “Mamiya/Sekor”.

The designers of this camera clearly thought about ergonomics as the deeply ribbed grip on the front of the camera allows for a better grip of the photographer’s right hand. Of course this grip is a far cry from the huge ones that would later adorn 21st century film and digital SLRs, it was a nice start and something that I am surprised more companies didn’t implement sooner. I wouldn’t freely dangle over the railing of Niagara Falls while holding this camera one handed, but for general purpose photography, the grip makes holding the camera comfortable.

Another ergonomic benefit is the over sized shutter speed controls, wind lever, and tapered focus ring on the lens. Each of these three design elements allow for better handling of the camera for people with large hands, or even normal sized hands but when wearing gloves. Users with small hands however, might want to look elsewhere as these design elements likely would have the opposite effect as the camera is quite large…and heavy.

Weighing in at 989 grams (~2.2 lbs) with the Mamiya ES 50mm f/1.8 lens mounted, this is one of the heavier SLRs in my collection, topped only by behemoths like the Nikkormat FTn and Canon EF.

At first glance, the top plate of the Auto XTL looks like any other 1970s 35mm SLR, but this is where you start to see some of the nice little touches that Mamiya incorporated into the camera’s design. On the left, things start off inconspicuously with an ordinary looking rewind lever. The centrally located pentaprism has a nice leatherette strip across the top, not unlike the classic design of the Zeiss Contax D. The shutter speed dial selects speeds 1 – 1/1000 plus Bulb, but if you look carefully, you’ll notice that its a bit larger than most cameras. The shutter release is next to it and like the shutter speed dial, is a little larger too. It has a concave top similar to modern “soft shutter releases” that you can buy on Amazon and screw into the shutter release socket on most modern cameras. Next to the shutter release, is the exposure counter, and it too, is over sized.

Next, we have the somewhat normal looking wind lever, but with a convenient feature. Taking a cue from Nikon SLRs, when the wind lever is pulled away from the body, it sits at about a 15 degree angle from it’s resting position ready to advance the lever for the next frame. There’s a little leatherette covered circle on the top of the center of the lever, which is actually a button that when pressed, draws the lever tightly against the body. This is a nice feature for left eye photographers such as myself who can sometimes find a protruding wind lever poking them in the eye.

Finally, when looking down at the top of the camera, or from the side, you’ll notice that the 50mm lens attached to the camera has a flared focus ring that is wider near the front of the lens than the back. All Mamiya ES-mount lenses for this camera have this flare, and it was done this way to help the photographer positively locate the focus ring with the camera to their eye.

The bottom of the camera contains a circular cover for the optional motor drive that was developed for this camera, rewind button, centrally located tripod socket and battery compartment for the S76/LR44 1.5v battery that is used to power the meter. The location of the tripod mount is significant as it allows for excellent balance when the camera is mounted on a tripod. The use of a 1.5v battery, as opposed to a 1.35v mercury battery was also significant since mercury batteries are no longer available today and the use of a modern equivalent would not have had any negative effect on the metering. Sadly, when I acquired this camera, the battery compartment was heavily corroded and the meter was inoperable on the camera. I did my best to clean off the corrosion (you can still see the pitting in the bottom plate), but I could never get it to work.

To load film in the camera, a simple tug of the rewind knob releases the removable right hinged door. This might not seem like much of a feature today, but in 1971, cameras with side latches, or even those like the Nikon F with an entirely removable back were still common, so having this type of door release was still pretty modern at the time. The entire film door could be removed, likely for some kind of bulk film back that was planned, although I am unsure if one was ever produced.

Film loads much like you would expect. A new cassette goes on the left, and the leader is attached to the non-removable take up spool on the right. The film pressure plate is a solid piece of nicely finished metal and has divots in it to reduce friction and the risk of scratches as film glides across it. According to Stephen Gandy’s excellent review of the Mamiya Auto XTL, there was a unique camera case with a hinge in the case itself allowing you to load and unload film in the camera without ever removing it from the case. I have never seen such a case, however.

Removing the lens from the camera is like any other bayonet mount SLR. There is a release button near the 4 o’clock position of the lens that when pressed, allows you to remove the lens with a quick counterclockwise twist. To reinstall the lens, line up the red dot on the camera near the 8 o’clock position with the red dot on the lens and twist clockwise until it locks in place. Simple.

Although the Mamiya Auto XTL used an all-new and proprietary lens mount, Mamiya shows it’s M42 screw mount roots with a special “P-Mount” adapter that was available for this camera which not only allowed 42mm screw mount lenses to be used, they also retained the automatic diaphragm feature of those lenses. This approach was also used by Franke & Heidecke with their ill-fated Rolleiflex SL35 from 1970. Available in the Auto XTL’s lens mount were 12 different Mamiya/Sekor lenses ranging from a 21mm f/4 wide angle, all the way to a 600mm f/8 telephoto. There was even a 90-230mm f/4.5 zoom lens!

The viewfinder of the Auto XTL is fully loaded, with a shutter speed scale along the bottom, like the Nikkormat FT series, an aperture scale along the lower part of the right side, and three square indicators, marked M, A, and S, for “Manual”, “Average” and “Spot”. The “M” indicator shows up whenever the camera is not in AE mode, and either the “A” or “S” shows up to indicate which metering option you have selected. Although this amount of information is nice to have, the Auto XTL was about a decade before back-lit viewfinder screens would become common, so it relied on light entering the lens to illuminate all of this information. In low lighting situation, these readings were useless. The two images below show a realistic shooting scene, along with the viewfinder pointed toward the sky so that you can better see everything.

On the side of the mirror box was a switch for an early form of exposure lock, which Mamiya called “Exposure Hold” which allows a photographer to capture a meter reading, and then hold it with a flip of the switch so that he or she may recompose their image. This would be useful in tricky lighting situations like in heavily back or fore-lit scenes. This is a feature modern photographers take for granted, but at one time, this was state of the art stuff!

Other features of the camera were an 8 second self timer, depth of field preview button, steel reinforced strap lugs, and an automatic resetting exposure counter. I cannot think of another camera made in 1971 with this long of a list of features. The Mamiya Auto XTL really is a spectacular camera both on paper and in person. One thing that really impresses me is how many of the camera’s features work really well. Mamiya did not design half thought out or poorly executed features. Every thing about this camera works well, from the flared focus ring to the over sized shutter speed dial. It’s such a shame that I could not test the camera’s electronic features as some careless previous owner left a battery in the camera for decades.

My Results

For the inaugural roll through the Auto XTL, I went out on a limb and loaded in a 20 exposure roll of Kodak Panatomic-X film that had expired in 12/1981. This roll of film was the only in my collection and one I acquired at an estate sale in 2016. I let this thing sit in my film cabinet for the past 2 years wondering when I should use it.

Shooting expired film is always a risk as you never know how well it was stored, or how well the emulsion has held up over the years. I’ve had great luck with film stocks like Kodak Verichrome-Pan and ORWO NP-55, but the Pan-X was new to me. This was originally an ASA 32 speed film, so it was quite slow to begin with. I did some research of other vintage film enthusiasts, and saw a recommendation to shoot it at box speed and see what happens, after all, I should be able to pull detail in Photoshop if things are underexposed, right? I decided to shoot the roll of film entirely in bright sunlight and use the Sunny 16 rule with the shutter speed fixed at 1/30 and see what happened.

Holy hell. I need more Kodak Pan-X! If you can believe it, there was once a time where I would have said I didn’t like shooting black and white film. I’ve learned better since then through a combination of improving my technique, developing my own film, and by trying different stocks. Kodak Pan-X was always a popular film, especially for news reporters for its fine grain, smooth details, and excellent shadow detail.

The film was originally an ASA 32 speed film that had expired in December 1981 and had been stored in unknown condition. Using my experience with very old black and white films, I thought that I probably wouldn’t need to vary much from the original speed. For safety, I shot it as an ASA 25 speed film. I set the shutter on the camera to 1/60 and shot most of the roll in brightly lit outdoor scenes varying the aperture from f//5.6 to f/11. When I got home I went online to see what kind of recommendations there were for developing Pan-X in HC-110. I struggled to find something online before checking the film’s box and seeing that the original development instruction sheet that came with the film said that HC-110 Dilution B worked well at 70 degrees for 4.5 minutes. I increased that to 5.5 minutes to account for the age, but otherwise did everything else the same.

The images from this camera are spectacular, and while the old Kodak film gets a lot of credit for that, the camera deserves some too. I was originally on the fence whether I would shoot this camera at all considering the meter was dead, but I am glad I did. The camera is large and heavy, but it never became cumbersome. The viewfinder was a tad dark compared to later SLRs, but since I was shooting everything outside, it was never a problem.

There is a lot to be said about an innovative camera that came out with features before other people did. There are many examples of cameras made that did something first, but weren’t always successful, and that’s what happened here. The Mamiya Auto XTL was a feature-rich camera, made for a professional market that never developed. It’s a shame really, as Mamiya had a long history of making excellent medium format cameras, and this model really seemed like they should have been able to transition that success to the 35mm market, but it never happened.

I waited a long time to find one of these to add to my collection and although it isn’t in the best of shape, the meter is dead, the body has a dent on it, and the self timer lever is missing, it still shoots wonderful photographs and was a lot of fun to use. I doubt this article will make a huge increase in demand for this special camera, but at the very least, I think anyone reading this should at least put it on their radar.

Additional Resources

https://www.cameraquest.com/mamyaxtl.htm

http://herron.50megs.com/XTL.htm

http://cjo.info/classic-cameras/mamiya-sekor-auto-xtl/

http://mamiya35collectors.com/mamiya-x-series.html

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-4068-Mamiya.html

For a beat up camera, the results are astounding. The images look like current digital. Well done. Another very interesting article. Thanks Mike.

Great review Mike! I’m a long term Mamiya fan, with already a RB67 Prod SD with a gazillian lenses, a Press Super 23, an assortment of 35mm rangefinders, and on the road for a Mamiya 7 for my birthday from my wife, closely followed with a TLR next year. I have never thought of the SLRs, and always, as you rightly pointed out most people think, thought of them as nothing special. I definitely do not want another lens mount too, so will end up maybe getting one of these and sticking to the 50mm. Must complete the set…..

Your excellent review mentions that this camera could be loaded or unloaded without removing the ever-ready case, but you’ve never seen one. There’s currently an Auto XTL case listed on eBay as item number 384416305114 showing the hinged rear panel which makes this clever trick possible. Perhaps the seller would allow you to use one of his pictures? Hope this helps.

Thanks for the heads up Dave! I took a look at that case and it does look interesting.

Holy hell is right. What wonderful film, and indeed, Mamiya came through again with a great little camera. Thanks for the review!