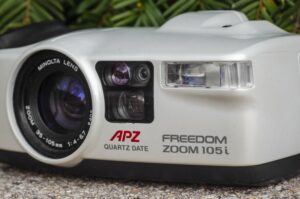

This is a Freedom Zoom 105i, a 35mm point and shoot camera, made by Minolta starting in 1990. The same exact camera was also sold overseas as the Minolta Riva Zoom 105i but otherwise the cameras are identical. Featuring a unique shape that sorta resembles a cross between an alarm clock and a pair of binoculars, the Freedom Zoom 105i was intended to be a new type of premium automatic everything camera. The camera featured Minolta’s most advanced automatic focus and automatic exposure features, adding to it the automatic eye start feature from their Maxxum SLRs in which bringing the camera to your eye begins focusing and readying it for exposure, and finally, something called APZ which was an automatic zoom feature, in which a CCD sensor in the camera detects the scene you are pointing it at, and attempts to select a focal length that is appropriate for the shot. With a uniquely designed body, a list of advance features, and Minolta’s reputation for quality, the Freedom Zoom 105i carried a premium price tag that kept it out of reach of most point and shoot customers.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 35 – 105mm f/4 – f/6.7 Minolta Zoom Lens coated unknown elements

Focus: 2.6 feet / 0.7 meters to Infinity @ 35-60mm, 3.9 feet / 1.2 meters to Infinity @ 105mm, TTL Phase-Detection Auto Focus

Viewfinder: Optical Zoom Finder with AF Crosshairs and both Flash and Focus Confirmation LEDs, 85% Field of View

Shutter: Programmed Electronic Shutter

Speeds: 1/2 – 1/500 seconds, step less

Exposure Meter: Two Segment Silicon Photosensor with Full Programmed AE

Battery: 6v 2CR5 Lithium Battery

Flash Mount: Built-in Body Electronic Flash, 18 feet / 5.5 meter max range @ ISO 100, 3.5 second recycling time, Anti Red Eye and Fill Modes

Other Features: Electronic Self-Timer, Eye-Start, Multiple Flash Modes, Manual Rewind Button

Weight: 635 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_riva_zoom-105_freedom_zoom-105i.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i came out at a time of change for cameras. It is a bridge camera that introduces a variety of new technologies, updating a proven formula. Like most Minolta cameras, it has a great lens, a good metering system and adequate auto focus. The camera’s biggest feature however, it it’s biggest weakness. The APZ Auto Zoom feature aims to solve a problem no one asked to be solved. In it’s efforts, it ends up getting in the way more than it helps. Still, the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i is a neat looking camera, with surprisingly good ergonomics that makes good images, as long as you don’t let the camera get in it’s own way. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.0 | ||||||

History

Only from the mind of Minolta…

If you watched TV in the 1980s, you likely saw a number of commercials from Minolta with this slogan. Although I was too young at the time to appreciate Minolta’s efforts, as I look back at their history, Minolta seemed to be the Japanese company that pushed the envelope more consistently than the others. That’s not to say that Canon, Nikon, Konica, or any other companies didn’t innovate, but thinking outside the box seemed to be an ethos at Minolta since the very beginning.

Minolta can trace it’s roots back to 1928 when a man named Kazuo Tashima created Nichidoku Shashinki Shōten and enlisted the help of two former German camera technicians to build German inspired Japanese cameras that had equal parts German DNA but with a unique Japanese design. Nichidoku didn’t want to simply copy German cameras, they wanted to make their own. Nichidoku would change it’s name in 1931 to Molta Gōshi-gaisha and the new company would build models inspired by other German makers.

The first Minolta camera was heavily inspired by the Plaubel Makina, but wasn’t an outright copy of it. Both the Minolta and Makina used a scissors folding design with removable backs for sheet and roll film and were aimed at the semi to professional photographer.

Later cameras like the first Minoltaflex were heavily inspired by the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex and Rolleicord TLRs. After world war II when the Minoltaflex became the Autocord, it used a unique bottom focus lever instead of a knob, a bottom hinged film door for easier film loading, and in 1958 a clever take on the LVS metering system in which aperture and shutter speed values are added together to match the correct exposure from a hand held meter.

Many of Minolta’s later cameras had innovative designs and features that weren’t complete departures from established designs, but weren’t copies either. The first Minolta 35 rangefinder borrowed a lot from the Leica, but had a unique viewfinder, front plate design, and hinged film compartment. The Minolta Auto-Wide was one of the first rangefinder cameras with a dedicated wide angle lens rather than a 40-50mm prime. In 1958, Minolta would beat other Japanese companies like Nikon, Canon, Konica, and Yashica to market with their first 35mm SLR, the Minolta SR-2. In 1963, the Minolta SR-7 would be released as the first 35mm SLR with a built in CdS exposure meter. In 1966, the SRT-101 became one of the first SLRs with open aperture through the lens metering and it’s CLC (Contrast Light Compensator) metering system was an early form of matrix, instead of spot or averaging, metering.

In the 1970s, Minolta swung for the fences and paired up with Ernst Leitz, working together on a number of projects that resulted in the Minolta CL in 1973 which was the first non-Leica camera to use the Leica M bayonet lens mount, the Minolta XE-7 in 1974 which was co-developed as the Leica R3, and in 1977 the Minolta XD-11 which was the foundation of the Leica R4 through R7.

The 1980s saw Minolta’s aggressive jump into the world of auto focus technology. The Minolta X-600 from April 1983 was a manual focus SLR that used electronic focus assist that would illuminate a light in the viewfinder when sharp focus was obtained. Next came the Maxxum 7000 in 1985 which was the first successful implementation of in-body automatic focus in a 35mm SLR. By being the first to the market with a interchangeable lens SLR with auto focus, Minolta led the market.

To Minolta’s credit, many of their innovative ideas worked well for the company, selling well and boosting their reputation in the industry. Between the Minoltaflex and Autocord, Minolta produced Rollei inspired TLRs from 1937 to 1966, the SRT-101 was in production from 1966 to 1981, and their Maxxum lineup of autofocus SLRs continued to be produced until Minolta and Konica merged together and eventually sold it’s technology and patents to Sony in 2006.

For all of their successes though, Minolta had a few whiffs, such as the Minolta Instant Pro, their lone attempt at an instant camera, which was nothing more than a rebranded Polaroid Spectra. There were two versions of the Minolta 110 Zoom SLR which attempted to combine the compactness of Pocket Instamatic 110 film into a zoom SLR, which resulted in one of the strangest looking cameras of all time. Finally, in 1984 came the Minolta AF-Sv, also known as the “Talker” which was the world’s first talking camera.

By the end of the decade, most other Japanese camera makers were onto what Minolta was doing and released their version of Minolta’s successful models (thankfully no one else made a talking camera), but Minolta wasn’t done with trying new things.

In the late 1980s, most cameras were of one of two designs. Single Lens Reflex cameras almost all shared a similar body style with controls in the same locations, and long lists of similar features. Point and Shoot cameras were generally similar to each other too. Usually some variation of a rectangular box, like a big bar of soap, there wasn’t a great deal of variation in point and shoot cameras.

In 1988, multiple camera makers all decided at once that the time was right to reboot what the world expected from camera design, and that the time was right to come up with some new designs. The term “bridge” camera was used to describe a whole generation of new cameras that didn’t look like, or function like the cameras that came before them. The first three bridge cameras to the market were the Yashica Samurai, Chinon Genesis, and the Ricoh Mirai. The Samurai was a fixed lens SLR that shot half frame 35mm images with a vertical film transport, similar to a motion picture camera. The Chinon Genesis was essentially a large auto focus zoom lens with a camera built around it. It worked similar to a camcorder and could easily be used with one hand. The Ricoh Mirai, was the strangest of them all, with a design that was like a cross between a portable boombox, a toaster, and an alarm clock, but with a large zoom lens in the middle.

Here are two articles about the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i. The first, is a one page review of the camera from the December 1990 issue of Popular Photography and the second is a point and shoot comparison from the December 1990 issue of Popular Mechanics.

Contemporary reviews of the camera were mixed. Some, such as the December 1990 preview called it a holiday best buy, praising it’s advanced technology. The later 5 camera Point-and-Shoot-Showdown ranked it 4th out of 5 pointing out it’s huge body was too big to be pocketable and that too much of the camera’s automation was automatic, but acknowledged that it performed admirably.

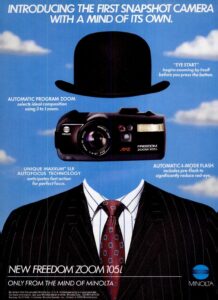

Retail prices for the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i were $512 for the pearl white version and $462 for the black version (this might be the only example where a black version of a camera was less than other options). When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to about $1160 and $1050 today which likely made it a pretty tough sell, especially for having such an unproven feature set.

As was common practice with many Minolta cameras, the Freedom Zoom 105i was sold in other markets as the Riva Zoom 105i, but otherwise was unchanged. An image on camera-wiki’s page for the camera shows a name variant called the Apex 105 which I believe was it’s name when sold domestically in Japan.

Whether or not you were intimidated by the camera’s large size or innovative automatic zoom, focus, and exposure features, Minolta proved once again they weren’t afraid to try something new. Even if the APZ feature didn’t pan out on the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i, it’s possible the company could have used the technology on something else later on down the road.

As it would turn out, they didn’t, and to my knowledge, the company never released another APZ camera (and if they did, it was so obscure, I haven’t come across one). But that didn’t stop Minolta from trying new things. Throughout the 1990s, the company would continue advancing their advanced consumer and professional level film SLRs and would even transition into the world of digital SLRs with models like the RD-175.

Today, Minolta is still a well regarded maker of fine cameras. Although the company had quite a few misses like the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i, it didn’t tarnish the company’s reputation and many Minolta cameras, from inexpensive point and shoots to top of the line SLRs are still desirable by collectors and shooters alike. Even if you had an entry level camera, Minolta made good lenses and even the cheapest Minolta could still make a great photo.

My Thoughts

Back in April 2016, I write a review for the Konica AiBorg, a 35mm superzoom camera that when it was released, hinted at a new era of camera design. Featuring an all black body with an integrated lens cap covering the large zoom lens, a huge LCD on the top of the camera with as many as 12 different shooting modes and an overall design reminiscent of Darth Vader’s helmet, it was a camera that evoked many emotions.

In that review, I declared it the worst camera I had ever used, and gave it, what was at the time, the lowest rating of any camera I had ever reviewed until that point. That review was written nearly 7 years ago, and surely since then, with all the cameras I’ve come across, I’ve found something worse?

The first time I saw a Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i, I didn’t immediately think of the AiBorg, as the two cameras look nothing alike, but as I played with the Minolta and realized they were both made in the same era of heavy experimentation in camera design, I realized that both represented each company’s attempt at trying something new.

The Minolta comes in two colors, grayish black, and a white pearlescent finish. My example had the white finish which I think adds a touch of elegance to the camera. It actually looks nice, and doesn’t seem gimmicky nor does it look like any other camera. The shape of the camera is more like an alarm clock or one of those compact desktop projectors. It is much wider than it is deep or tall, giving it a very unique feel. At 635 grams, the camera is heavier than you would have expected from an almost entirely plastic camera.

Unlike the AiBorg, the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i’s claim to fame is not a ridiculously long list of features, but rather one signature feature that someone at Minolta likely thought could be the next big thing. As a result of it’s small feature set, the camera’s ergonomics are on the simple side.

On the left side of the top of the camera are two round black buttons labeled ‘T’ and ‘W’ for tele and wide. This controls the zoom throughout it’s 35mm to 105mm range. Pressing and holding both the ‘T’ and ‘W’ buttons for about a second deactivates the camera’s automatic zoom mode until the camera is powered off and back on again. The viewfinder has a small hump, but not accessory shoe, and it’s not until you get across a sea of white plastic to where the right side has a black plastic contoured grip which includes the round shutter release button. The location of the two zoom buttons and shutter release are comfortably located in the exact positions my left and right index fingers naturally lay when gripping the camera like a set of binoculars. I have what I would describe as “average adult male sized hands” so children or those with much shorter fingers might find these locations out of reach, however.

On the base of the camera are two corresponding round divots that are comfortable resting places for your left and right thumbs when holding the camera. It is clear that some thought was put into the handling ergonomics of the camera as I found it to be very comfortable to hold.

The rest of the bottom of the camera has a small recessed manual rewind button near the back edge of the door, the camera’s serial number, a centrally located metal 1/4 tripod socket, and a door for the 2CR5 lithium battery.

Both sides of the camera have a strap loop for use with the original Minolta strap that came with the camera. Near the bottom of the left side is a sliding black door release for opening the film compartment. I rarely discuss camera straps as there’s usually not much to say, but the strap that comes with the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i is one of the best I’ve seen as it doubles as both a traditional neck strap but also a wrist strap. Around back is a rubber pad for making contact with the back of your neck when using it that way, but nearer the right side of the camera is a second padded rubber/vinyl/pleather strap for your wrist. If you so choose, you can wrap your hand around this strap and then by gripping the contoured right side of the camera, using it single handed. The camera is a tad heavy to be hanging from your wrist for an extended period of time, but for short uses, it works quite well and is very comfortable.

One feature of the camera I rarely talk about is the lens cap, which on the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i not only covers the lens, but also the viewfinder, which is convenient as you’ll never remember to take off the cap when looking through the viewfinder as it will be totally dark with the cap on. Some previous owner of this camera used a third party SIMA tether on the cap to keep it connected to the neck strap, which is probably the reason it hasn’t become lost over the years.

The back of the camera is where the most number of controls are located. First, on the far left edge is a rectangular window for reading the type of film loaded into the camera. Near the top of the door, slightly off center, is the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder. To the immediate right of the eyepiece are orange and green LEDs which indicate slow shutter speeds and flash readiness respectively. Although the two LEDs are external to the viewfinder, they are close enough that you can easily see them in your peripheral vision while looking through the viewfinder. Below the viewfinder is a proximity sensor for Minolta’s “Eye-Start” technology which readies the camera upon bringing it up to your eye. This feature was prominent on Minolta’s Maxxum SLRs, and also appeared on some of their higher end point and shoots like this one.

To the right of the eyepiece is a rubber self-timer button, LCD status screen, and a rubber flash button. The LCD displays all of the most commonly used settings for the camera, showing exposures taken on the roll, film transport, flash mode, zoom mode, and self-timer status. Beneath the main LCD is a smaller LCD for the date back, and three recessed buttons for setting the date back’s modes. Finally near the bottom right corner is the sliding power switch with an On and Off setting. Thankfully, even with the switch in the On position, the camera will automatically power off if no buttons are pressed within an hour.

Opening the right hinged film door reveals a modern and somewhat interesting film compartment. For starters, with such a busy back to the camera, combined with the extra long width of the body, the rear door is unusually heavy. Be careful when opening it not to put too much pressure on the hinge as I would suspect this could be a failure point of the camera. The Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i supports both DX encoding and has a quick load feature. Simply insert a DX capable cassette into the chamber on the left and draw the leader out to a yellow sticker beyond the take up spool on the right, close the door, and the camera will auto set the film speed and load the film for you. The camera supports film speeds from ISO 25 to 3200 and if non-DX encoded film is inserted, the camera defaults to ISO 25 with no option to override it. This is unusual as most DX equipped point and shoot cameras will default to ISO 100 when a non-DX cassette is used.

A very interesting feature of the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i is that when looking at the film compartment, it has what appears to be a vertically traveling focal plane shutter, like an SLR, however, this is not the camera’s main shutter. The camera uses a standard behind the lens rotary shutter, as you’d expect to see in any number of point and shoot cameras. The purpose of the focal plane shutter appears to be a requirement of the auto zoom feature.

I’ve found no technical information about how the camera works, but upon staring at the front and rear of the shutter while shooting the camera, I observed that the front shutter is always open, even when the camera is off. Sensors behind the lens are used to detect the distance of objects for use with the automatic focus and zoom features. Once a distance has been locked in, pressing the shutter release, first closes the front shutter, then the rear shutter opens, and then at the moment of exposure, the front shutter opens and closes at whatever shutter speed the exposure metering system decides. This sequence of events is very similar to that of leaf shutter SLRs, in which the front leaf shutter must open and close twice for each exposure, and using a capping plate in the film gate, the film is protected from light while the main shutter is open. Although this whole sequence happens relatively quickly, it is not instant, and when shooting the camera, hearing two sets of shutters, plus the various moans and groans of the film transport lead to a very noisy exposure sequence. Why Minolta couldn’t have just used an actual focal plane shutter to control everything would have made things simpler, quieter, and faster, but perhaps this method was cheaper.

Up front, there are no controls for the camera, but there is still a lot to see. For starters, the 35mm to 105mm Minolta Zoom lens is threaded for 40.5mm filters although I wouldn’t recommend using them as the camera’s metering system is not through the lens, and without any method for manual control or exposure compensation, putting anything other than a clear UV filter would result in underexposed images.

To the right of the lens are three windows, the first is tinted red and hides an active infrared beam which is used with the internal auto focus system for greater accuracy in low light. To its right is the exposure meter window, and finally, beneath is the opening for the viewfinder. Although not mentioned in the manual, the design of the viewfinder appears to be some type of porro-prism design which was likely chosen as it would allow the viewfinder to be coupled to the lens zoom. Finally, to the right is the in-body electronic flash.

The viewfinder is bright and shows center hash marks to indicate both the central metering and focus point. The design of the viewfinder is one of those in which the edges quickly darken if your eye is not perfectly centered in the middle. This can be an issue for people like me with prescription glasses as there is a very specific sweet spot your eye must be in to see the entire image.

Apart from green and orange LEDs on the side of the eyepiece which I previous mentioned, no other information is visible in the viewfinder. The viewfinder is coupled to the focal length of the lens. As you zoom in or zoom out, the image in the viewfinder corresponds. There is no indication of what the actual focal range is however.

The automatic zoom feature of the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i is the camera’s highlight feature, and it is clear that Minolta made an effort to cater the camera’s controls to that feature. While I would have liked to have seen a few more options like exposure compensation or maybe even manual control over the meter, Minolta wisely didn’t overcomplicate the camera with excessive shooting modes like the Konica AiBorg. Despite how it looks, the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i is a point and shoot camera. You turn it on, point it at something, press the shutter release, and the camera does the rest. But how does it all work? Over the course of the 20th century, photographers consistently balked at the introduction of the auto exposure era, and then again with auto focus, but how would they react to automatic zoom? Keep reading.

My Results

For the first roll through the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i, I put in a roll of “new to me” Kodak T400CN black and white film. For anyone whose never heard of this film it is a black and white film that is developed using C41 chemicals. My understanding of it’s construction is that it’s color film, just without the color layers. The reason this film exists is that with the increased use of minilabs used to develop film, having two sets of chemicals, one for black and white, and one for color film was less practical for smaller operations. To allow for more people to still shoot black and white, C41 based black and white films like T400CN and Ilford XP2 were created allowing labs to develop both black and white and color in the same machines.

This film was expired, but I had shot some of it before and knew that it would still expose nicely, if with a bit of extra grain. I would be shooting this camera in the dead of winter, so I assumed it would balance nicely with the high-contrast grit of winter landscapes.

I’ll start off by saying, that the expired Kodak T400CN film did not hold up as well as other rolls of the same film had. Usually black and white films hold up much longer than color films do, but this being a C41 film, it would appear that the loss of contrast and muddy grain that plagues expired color film also applies to this film. While the images weren’t terrible, an increase in grain and loss of shadow detail is evident.

Looking past the issues with the film, there is still a lot we can see about the performance of the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i. As should be no surprise, the 3x Minolta zoom lens is a solid performer. I was unable to find any information about the make up of the lens, but my best guess is it is somewhere between a 12 and 14 element design. As with most point and shoot zooms, you aren’t going to get the same razor sharpness of a prime lens, but overall, images at minimum to maximum focus are very good, and easily would have pleased the target customer who would have considered buying this camera when it was new.

Sharpness is good corner to corner, with some vignetting and softness evident at the wide angle of the spectrum. When zoomed to 105mm, the vignetting went away, but the image got slightly softer. I did not shoot any color in this camera, but my guess is the modern lens coating would have rendered accurate colors with pleasing contrast.

I noticed that the metering system tended to error on the side of underexposure as a few images, especially those indoors came out muddy. Having not shot a modern-ish point and shoot in a while, I kept forgetting to turn off the in-body flash, which even if you remember to do, turns itself back on each time you power cycle the camera. This results in darkened interior shots on anything behind the reach of the flash. Several of the indoor shots of the mall are dark for this reason.

I also noticed that on occasion the focus system was off. The image of the elk head is strangely soft, even though the focus area was dead center in the frame. This was pretty common with point and shoot cameras of the era, as most did not offer infinite focus, and rather used stepped zones which rely on depth of field to get things in focus.

Despite using less than ideal film, and my own forgetfulness with the flash, overall, the images turned out pretty nice. As is the case with nearly every Minolta camera ever made, the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i is capable of nice images, but that’s not really the story of this camera.

The signature feature of the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i is the APZ “automatic zoom” feature, which plainly…sucks. In the history of camera design, photographers have always been reluctant to adopt all types of automation. Auto exposure, auto film loading, auto focus, and automatic flash were all at one time new, but eventually evolved into useful features that cameras today do quite well. Automatic zoom however, where a camera attempts to match the focal range with the focus distance is a solution to a problem no one asked for.

While researching this article, I never found any type of technical explanation for how APZ works. Today, there is a lot of talk about AI where computers can look at something and make intelligent decisions based on known variables. In 1990 when this camera was built, AI didn’t exist, and anything that resembled it, was extremely rudimentary. In my time with this camera, my observation is that the APZ system doesn’t quality as AI, rather it couples the zoom feature with the focus distance. Images focused farther away, and the lens zooms to telephoto. Images focused close up, and it moves to wide angle. There is no software in this camera analyzing the scene which you are pointing the camera at and making decisions based on what will look good and what won’t. Quite simply, far away = telephoto, close up = wide angle. If you want something other than that, and you need to override it.

It was this constant need to override the APZ system that tainted my time with the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i. To their credit, Minolta makes overriding the system pretty easily, but in my test with this camera, I really wanted to stick to using it, as that’s kind of the whole point of this camera, but it got to the point where by halfway through the first roll, I became so annoyed that I was eagerly pressing the shutter release just to finish the roll. I knew before that first roll was finished that I likely would not be shooting a second roll through it.

Whatever misgivings I have about using the camera, I did find myself admiring it’s looks. Where most “bridge cameras” were exercises in questionable design choices, the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i both looks good and it makes good images. The ergonomics of the top zoom controls and shutter release are perfectly located. The size and thickness of the body were perfect for my hands, the two divots on the base of the camera were exactly where my thumbs expected them to be, and with the extra safety of the wrist strap built into the next strap, I felt comfortable holding the camera for long shooting sessions.

It is clear that Minolta took some chances with both the automatic zoom feature and the camera’s design, and quite simply, the design was pretty good! Sadly, the APZ feature was what this camera was about, and when that didn’t appeal to customers, this format of camera disappeared. I can’t help but imagine what a more normal 35mm point and shoot bridge camera with more manual control and a lens with a larger zoom range, but no automatic zoom feature, might have been like. I think it would have a winner!

With that in mind the Konica AiBorg’s title as “worst camera I’ve ever shot” is still in tact. Like it, the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i took some chances, but overall is a much better camera that does more right than wrong. I just cannot say that about the AiBorg.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Minolta_Riva_Zoom_105i

https://filmandsensor.com/this-is-a-weird-camera-minolta-freedom-zoom-105i/

https://cameragocamera.com/2022/03/04/minolta-riva-zoom-105i/

Great review, Mike! Some of these 90’s zooms are so weird looking.

As for the APZ, I have a Minolta Freedom Zoom Date 9T. It has “ASZ” which stands for “Auto Stand-By Zoom”. It seems to work similarly to the APZ (I just tested). Thankfully it has a simple on-off button, so Minolta learned their lesson, I guess. (Though turning the camera off does not reset the ASZ.)

Despite its shortcomings, the camera’s design, ergonomics is good. I like the Minolta Freedom Zoom 105i’s unique appearance and the ability to capture good images were notable aspects. Thank you for sharing your review and insights!