This is a Nikon E2Ns, a digital SLR produced in joint cooperation between Nikon and Fuji in 1996. The E2Ns is an update to the earlier E2 and E2S models from 1995 expanding the available ISO speeds and improving the camera’s speed. All E2 models shared the same 2/3 inch 1.3 megapixel Charged Coupled Device (CCD) sensor. The body itself is based off the Nikon F4 35mm film SLR and shares that model’s mechanical shutter, auto exposure and auto focus systems, and Nikon F-mount. The abnormal thickness of this camera is due to an internal focusing lens that refocuses the light passing through the lens onto the smaller 2/3″ sensor, maintaining the correct focal length, so despite having a sensor smaller than full frame, the captured image maintains the same focal length as whatever lens is mounted. A version of this same camera was sold by Fuji as the Fujix DS-515A with identical specifications.

Sensor Type: 1.3 Megapixels 2/3 inch Vacant Transfer CCD

Storage: 1x PCMCIA/PC Card Type I/II Drive

File System: JPG, TIFF (Nikon File System)

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 AF Nikkor coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Nikon F Bayonet

Focus: In-Body TTL Phase Detection Focus, Supports Nikkor AF and AF-S lenses

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism with electronic focus confirmation, and full information LED display, 98% Coverage, 0.7x Magnification

Shutter: Electronically controlled, vertically traveling focal plane shutter

Speeds: 1/8 – 1/2000 seconds, Electronically Controlled

Exposure Meter: TTL 3D Matrix, Center-Weighted, Spot, with Programmed, Av, Sv, and Manual modes

Sensitivity: ISO 800 Equivalent (STD) and 3200 (HIGH)

Battery: Nikon EN-1 Rechargeable Battery, 7.2v 1200maH Ni-Cd Rechargeable or Nikon ES-1 AC Adapter

Flash Mount: Nikon Speedlite Hot Shoe, 1/250 second X-sync

Weight: 2056 grams, 1894 grams (no lens), 1662 grams (no battery or flash card)

Manual (original E2/E2S model): https://cdn-10.nikon-cdn.com/pdf/manuals/archive/E2-E2S.pdf

Manual (E2N addendum): https://www.manualslib.com/manual/111356/Nikon-E-2-S.html

How these ratings work |

The Nikon E2Ns is a historically significant DSLR that came out during the infancy of the digital photography landscape. The camera is very big and heavy, and lacks many of the conveniences we take for granted with modern digital cameras such as a rear LCD screen, USB support, and more than two settings for ISO. Despite the early limitations, the camera largely works like a later DSLR and requires no special instruction to use. The images it makes certainly don’t compare to later cameras, but were good enough for the era it was made to make small prints from and clearly would have given it’s early adopters a taste of what was to come. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +2 for historical significance | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.0 | ||||||

History

The Nikon E2Ns might say “Nikon” across the front of the pentaprism hump, and might have a Nikon F-Bayonet mount, and it might support a large range of Nikon lenses, but this camera is almost equal parts Nikon and Fuji. For anyone who thinks that’s weird, Nikon and Fuji had a long relationship jointly developing digital SLR cameras for well over a decade.

Before that though, in 1986 Nikon (then still called Nippon Kogaku) made it’s first foray into “filmless cameras” with something called the Nikon Still Video Camera Model 1. The SVC-1 was jointly built with Matsushita Electric, owners of the Panasonic brand, and came in body strongly resembling a film SLR of the day. It featured an all new QV-bayonet mount which was different from the Nikon F-mount but is said there was an adapter to allow F-mount lenses to work with it.

It had a 0.3 megapixel black and white sensor and saved images to an external 2″ micro floppy disc drive. Although no information regarding the size or technology of the sensor exists, that the kit lens was said to be 6mm f/1.6 suggests an extremely small sensor. In a Swedish article covering the announcement of the SVC-1 translated on nikonweb.com, it says that mounting a normal Nikkor lens using the adapter would result in an equivalent image of around 200mm. This could suggest that the camera’s sensor had a 4 to 1 crop factor.

Although the camera and lens were shown at Photokina ’86, interest was underwhelming and the camera was never produced beyond the prototype stage. Still, the seeds for continued advancement of filmless cameras were planted and more would be soon to come.

For Fuji, the company took an approach similar to Eastman Kodak in pioneering it’s own line of electronic still video and early digital cameras. The first Fuji camera was also the very first consumer digital camera. It was called the Fujix DS-1P, and it was a compact consumer oriented point and shoot that shot 0.4 megapixel images, storing them on a 2MB flash card. Like the Nikon, the Fuji was only shown as a prototype as the cost to produce the camera was almost certainly a lot higher than the quality of it’s images could justify.

Both Nikon and Fuji would continue to develop electronic still video cameras, eventually creating real digital images that no longer wrote analog video. Nikon’s approach was to pair up with other technology companies making “hybrid” digital cameras out of film bodies. Nikon would produce at least one more camera with Matsushita called the Nikon QV-1000C in 1988, with Kodak the Kodak Professional DCS, and in 1994, the Fujix DS-505/515.

The Fujix DS-515 came first, followed by the simpler DS-505 a year later, and had a body based on the Nikon F4 film camera. Nikon would also sell the camera under it’s own name as the E2. Variations of the camera called the E2S, E2N, E2NS, and E2i. Unlike previous digital SLR systems, the Fujix and Nikon E2 cameras were entirely self contained cameras that had similar features to and worked similar to regular 35mm film SLRs of the era.

All of the Fujix and E2 variants shared the same 1.3 megapixel 2/3″ CCD sensor that output color images with a resolution of 1280×1024. The cameras all supported the Nikon F-mount and were compatible with all of the same lenses that could be mounted to the Nikon F4. Storage was via a PCMCIA/PC Card type I/II drive located where the film compartment would be. Because of the large size of the PC Card drive, there was no room for a rear LCD allowing you to preview images after they were taken.

Variations of the two Fujix and five E2 models were largely improvements to the camera’s speed, ISO sensitivity, and the frame buffer, allowing for more consecutive shots to be taken. The E2i is the least common and was intended for medical use, sold with an adapter allowing it to be mounted to a microscope.

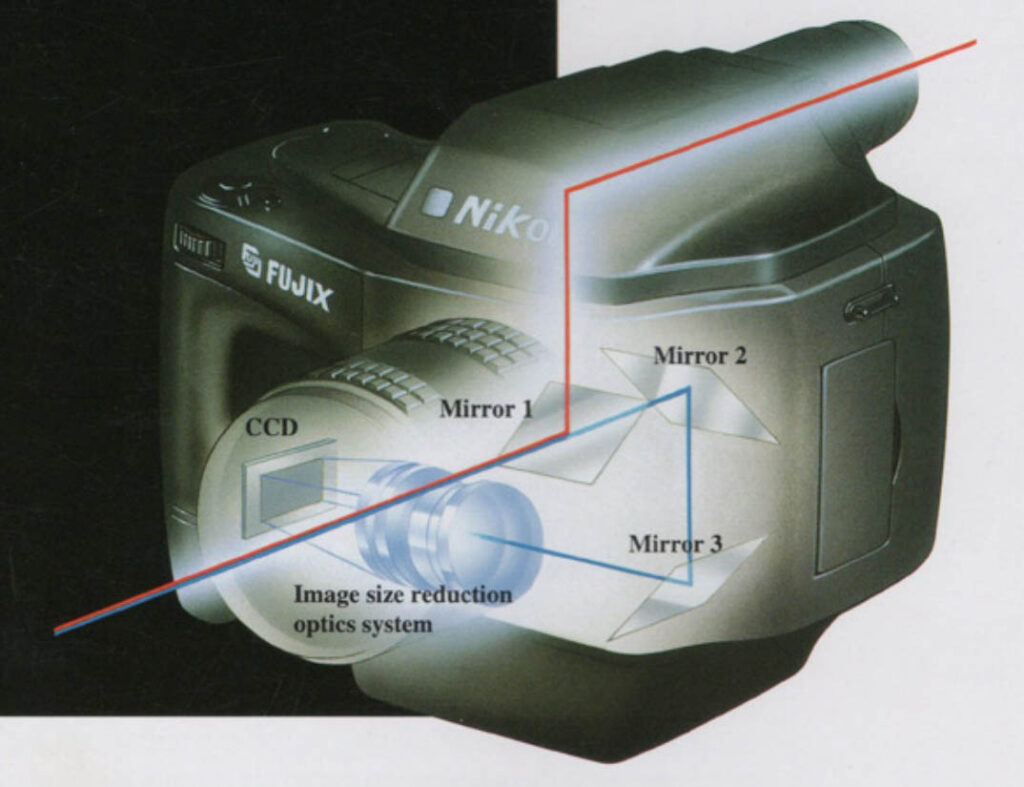

The first time you see one of the Fujix or Nikon E2 models, the most striking characteristic is it’s size. While most early DSLRs were larger than their film equivalent as they needed additional space for their storage system and digital backs, the Nikon E2 was much thicker front to back than you would expect.

This is a result of what Nikon called the “Reduction Optics System”. The Reduction Optics System was a method that would internally reduce the image size of light coming through the lens, down to the smaller 2/3″ CCD. In modern digital camera terms, the E2 had a crop sensor, in which the sensor physically smaller than the 24mm x 36mm exposure from a film camera. When mounting lenses intended for film cameras into digital cameras with a crop sensor, the focal length is reduced by whatever the crop factor is. On an APS-C camera, the crop factor is 1.5x, so mounting a 50mm lens on an APS-C camera results in an equivalent 75mm focal length. Using a Micro 4/3rd camera, the crop factor is 2x, so that same 50mm lens will have an equivalent focal length of 100mm.

The E2’s 2/3″ sensor would have a crop factor of 3.9x, so mounting a 50mm lens would result in an equivalent of 195mm, which was not ideal. To combat this, the light path entering the E2’s lens, passes through a focal plane shutter in the usual locaiton, but then hits a series of mirrors that reflect the light through a 3-group lens to reduce the light down to the 2/3″ sensor without changing the focal length. This allows the use of nearly the entire selection of Nikon 35mm film lenses to work on the E2 without having to worry about a crop factor.

Technicality: This actually isn’t 100% true as the Fujix and E2 cameras output images with a resolution of 1280×1024 which means they have an aspect ratio of 5:4, as opposed to 35mm which has an aspect ratio of 3:2. This results in a horizontal crop of about 1.2x.

Although the optics used in the Reduction Optics System, is it impossible to add glass elements without adding some distortion. Furthermore, as light passes through these lenses, the effective maximum aperture is reduced to f/6.7 via a separate diaphragm. It doesn’t matter how fast of a lens you mount to the Nikon E2, you won’t get an f/stop faster than f/6.7 as the diaphragm on the lens is not used. To compensate for this, the standard ISO is set to 800. A higher speed ISO is also available which varies between ISO 1600 and 3200 depending on which variant of the E2 you are using.

With the release of the Nikon E2 series in the US, the world got it’s first glimpse into what a complete digital camera system could do. Of course there were earlier DSLRs, but most like the Kodak DSC series were aimed exclusively at the pros and likely were never seen by consumers, and early electronic still video cameras were seem more as electronic gadgets, than real cameras.

Of course, I should take a step back and admit that my use of the word “consumer” deserves a big fat asterisk next to it, as the Nikon E2 was not a cheap camera. With a MSRP of $13,995, it cost more than some automobiles did at the time, but amazingly was about half the cost of the Kodak DSC 460 at $27,995. Actual street prices you could expect to pay for a Nikon E2 were a bit less however, with prices as low as $12,000 often cited in articles around 1996. But whether you’re talking about a $12,000 camera, or a $13,995 camera, when adjusted for inflation, those prices compare to $22,700 and $26,500, an absolutely massive price to pay for a camera.

To help spread knowledge about their new camera, Nikon produced a pamphlet explaining the cameras features and technical details, offering it to dealers in the hope that they would be able to explain the camera’s benefits to potential customers. The following PDF of that pamphlet is courtesy of nikonweb.com.

For a cutting edge piece of technology that came out at a time several years before the widespread adoption of digital photography, the Fujix DS-505/515 and Nikon E2 cameras were moderately successful. They may not have sold in huge numbers, but they proved not only to Fuji and Nikon, but to the entire world that an interchangeable lens digital SLR system could exist. Sure, the technology was still very early and needed to advance quite a bit to match the quality of regular 35mm, but with advancements soon to come, the days of 35mm as the dominant form of photography were numbered.

A follow up to the Fujix DS-505/515 and Nikon E2 appeared in 1999 as the Fujix DS-565 and Nikon E3/E3S with a reduced price and a bunch of incremental changes. The new camera came with an updated 1.4 megapixel 2/3″ CCD sensor that produced slightly higher resolution 1364×1032 images in a slightly more rectangular aspect ratio. Improvements to the Reduction Optics System improved the maximum aperture to f/4.8 from f/6.7 and a third mid ISO setting of 1600 was added.

Other updates were improvements to the Matrix Metering System, a faster SCSI interface and larger buffer allowing for more consecutive exposures, updates to the white balance system and a host of other software improvements. The price was also reduced to $7500, which was still high, but it attracted anyone wanting to shoot existing F-mount lenses without any crop factor.

After the release of the Fujix and Nikon E-series series, both Fuji and Nikon would continue working together for another decade. In 2000, an all new model called the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro would be released in a much more traditional DSLR shape. The camera used a Fuji developed 3.4 megapixel APS-C Super CCD that through software interpolation, could output files up to 6.1 megapixels. The camera had a familiar rear LCD like modern DSLRs and no longer required the use of the bulky Reduction Optics System.

In 1999, Nikon would release their own fully developed Nikon D1 DSLR which introduced a new line of crop sensor friendly DX lenses that did not require any sort of internal Reduction Optics System. Full frame 35mm film camera lenses could also be used, although with a modest 1.5x crop factor. Nikon and Fuji’s relationship would continue for three more models, the FinePix S2 Pro, S3 Pro, and S5 Pro (there was never an S4 Pro). The FinePix S5 Pro was the last in the series and was discontinued around 2009. Unlike the Nikon E-series, the Fuji FinePix cameras were only sold under the Fuji name, there was never a Nikon branded equivalent as by that time, Nikon was already marketing their own line of similar, but different cameras.

In the first decade of the 21st century, both Nikon and Fuji would continue to have success, but in different areas. Fuji would eventually get out of making DSLRs, but would continue producing a wide range of digital point and shoot and bridge cameras. Nikon would continue to be successful with DSLRs, digital point and shoots, and eventually digital mirrorless cameras, up through the current Z-series, which is still made today.

Digital photography would quickly eclipse the film industry, with digital camera sales out performing film by huge margins, and by 2010, almost putting the entire industry out of business. Digital cameras would continue their reign into the 2010s, but would discover new competition with smartphones. Although still technically considered digital cameras, the cameras contained in smartphones would surpass that of most consumer point and shoots, offering a level of flexibility and software manipulation that even the highest end cameras today can’t match. That’s not to say that dedicated digital cameras are dead, it’s just that like film, they’ve had to find a new way to stay relevant in the current marketplace.

Today, as film and film cameras grow in popularity, there is renewed interest in older digital cameras too. Point and shoot “digicams” from the mid to late 2000s are in huge demand. Although digital SLRs from the 1990s may not be the most usable cameras, there is a growing legion of collectors for old digital cameras. Their historical significance and sometimes unorthodox features and ergonomics make them appealing to collectors. Finding any of the cameras in the Fujix or Nikon E-series is hard to do today, and when you do, their rarity drives up the prices. These are neat cameras to own and if you can find one that works, they’re fun to shoot, if only to see what people had available to them in the early days of the digital revolution.

My Thoughts

A recurring theme I’ve discovered as I continue to review old cameras is that those with more unusual features, controls, or designs are the ones that stick out to me the most. While a huge number of 35mm SLRs, Japanese rangefinders with 2.8 lenses, and folding German cameras were made over the past century plus, each of their operation is very similar to others of the same design. Sure, there are some exceptions, the Ihagee Exakta Real, Teraoka Auto Terra Super, and Kodak Regent stand out in each of their respective sub-genres, but when it comes to a camera that you really need to jump through hoops to use, it’s hard to beat early digital cameras.

I’ve written about the 3.5″ floppy disc based Sony Mavica MVC-FD88, the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro with it’s 7 batteries, and the Nikon based but Kodak built full frame sensor Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n, but with the exception of the Mavica from 1999, the end of the 20th century seems to be a stopping point for early digital cameras. To find models, especially those in working condition from before Prince’s favorite year to party, is incredibly difficult. I had a couple leads on a few, but none that were working.

When fellow Camerosity Podcast host, and everyone’s favorite supplier of GAS, Paul Rybolt alerted me to this nice looking and fully functional Nikon E2Ns, I begged him to let me try it out. I had seen these cameras before but they were always in pieces, never including a working battery or charger, and with my experience using early digital cams, I had never wanted to pull the trigger until I knew one would work.

Paul agreed to send me the Nikon/Fuji love child and upon it’s arrival, the very first reaction I had to the camera was it’s size. This thing is HUGE! In the image to the right, I have it posed next to the Nikon Z5, which was released in 2020, only 24 years later. The difference in 24 years is the same as the Nikon F vs the Nikon F3, yet a 24 year difference between digital cameras is a lifetime! The Nikon Z5 looks like a toy next to the monster E2Ns, and the Z5 isn’t exactly small either!

With a weight of 1894 grams without a lens mounted, things escalate quickly depending on what glass you have attached to it. The E2Ns isn’t just heavy though, it is large in every physical dimension. At a height of almost 6 inches tall and nearly as thick, this is the largest non medium format SLR I’ve ever handled!

The E2Ns is like most early Nikon DSLRs as it is based off a film SLR, but unlike those others which generally retain the film camera’s primary controls, the E2Ns looks considerably different. The entire top plate is unique to this camera as is it’s LCD display screen.

On the left are four buttons whose functions can be scrolled through using the command dial on the right side of the camera. The four buttons are for exposure mode, metering mode, exposure correction, and ASA sensitivity. In the center is a typical Nikon Speedlite shoe. The additional contact points make this camera TTL flash compatible with any number of Nikon Speedlites from the late 1990s to early 2000s. This is one area where the camera shows it’s Nikon F4 roots as it does not have a pop up flash.

On the right is the trapezoid-shaped LCD display which shows the typical variety of information you’d expect to see on any digital camera. I won’t explain them all, but a couple highlights are that the f/stop readout will never go below f/6.7, even with a faster lens attached. This is because of the E2Ns’s inner reduction lens, which I explain in the history section above. Of the four quality settings, the ‘Hi’ setting tells the camera to shoot in uncompressed TIF mode. This is not the same thing as RAW mode and requires Nikon’s special software to open. The other three settings output regular JPGs in various levels of compression. Finally, there are only two choices for Sensitive, ‘HI’ which sets the ISO to a 3200 equivalent, and ‘STD’ which is 800. There are no other choices for ISO.

Above and to the right is the shutter release button, surrounded by a drive mode and shutter lock setting. A small button to the left must be pressed to change this ring from any setting, preventing accidental mode changes. In the bottom right corner is the command dial, which when rotating with a combination of buttons and settings on the camera, cycles through available options. Finally, there is a metal strap lug which when paired with another sticking out of the other side of the camera helps balance the camera while hanging from your neck.

The bottom of the camera has a sicker with things like serial number, who made the camera, and various other certifications that the camera has passed. In the center is a 1/4″ tripod socket, whose location helps to balance this very heavy camera on a tripod.

On the other side is a release lever for the rechargeable battery pack. The Nikon E2Ns uses a special 7.2v 1200maH Nikon EN-1 Rechargeable Ni-Cd Battery or a Nikon ES-1 AC Adapter made specifically for this camera. Replacement EN-1 batteries are no longer available and with these reaching a quarter of a century old, it’s unlikely you’ll find one that still holds a charge, so if you want to use this camera, using the ES-1 AC Adapter is your only option.

Around back is the large F4 style eyepiece for the viewfinder. The E2Ns supports the same number of viewfinder accessories as it’s film based models do. Above the large contoured rubber hand grip are dedicated buttons for AE and AF lock.

In the middle is the most glaring difference between the E2Ns and other DSLRs, which is the absence of an LCD monitor for previewing images or navigating the camera’s menus. In the early days of digital cameras, the idea of a LCD screen on the back was not yet standardized and likely would have added considerable cost to what were already expensive cameras. So, like you do with film cameras, you cannot see your image on the camera until after getting the images out of it.

In it’s place is the bay for the PCMCIA/PC Card type I/II drive. A sliding lock switch also doubles as the eject mechanism for the PC Card. Simply press in on the lock while pulling out and the entire mechanism pops up and the card is ejected. The Nikon E2Ns manual specifically calls for a Nikon Image Memory Card EC-15 of unknown capacity which I did not have. When the camera came to me, it included a variety of third party PC Cards. Unfortunately, having no way to read PC Cards in my Windows PC directly, I went and bought a CF Card to PC Card adapter which worked well.

The camera’s thickness and ungainly proportions are most obvious from the side. From the surface of the desk, the E2Ns stands nearly 6 inches tall with the lens seemingly floating 2 inches off the flat surface. With no controls on this side of the camera. looking at the side profile, you’d be forgiven if you assumed this was some kind of NASA camera or something designed for use in a lab.

The camera’s left side has a lot more things to see. Near the front are two output connectors. The yellow port on top is an analog composite video out for connecting to an analog TV. When connected to a TV, the camera mode selector around the shutter release must be set to PB. The bottom connector, despite saying Digital Out, is not for digital video as HDTV was not in widespread use when this camera was made, but rather for connecting to an optional EX-10 external sync adapter that was available. Above and to the left of the yellow video out is a small button which can be used to lock the Command Dial on top of the camera, preventing accidental changes to the camera’s settings.

Next to these ports is a hinged door that when opened reveals some extra buttons for things like image quality, white balance, date imprint, formatting and erase buttons for the memory card and a couple others. Lastly, a sticker suggesting that you RTFM is a nice touch. I can think of many more cameras that could have benefitted from a sticker like this!

The Nikon E2N2 uses the Nikon F-mount which means it can physically mount nearly any Nikkor or third party F-mount lens ever made. On pages 73 – 76 of the camera’s user manual, a lens compatibility chart warns that certain wide angle, fisheye, and slower lenses may cause vignetting. Interestingly, the 50mm f/1.8 AF Nikkor that I used for this test was one of the not-recommended lenses, but I did not know that prior to shooting it.

In any case, since the camera uses Nikkor lenses, how you interact with it is going to depend on which lens you are using, but for the sake of being thorough, to the left is an image of what the 50 / 1.8 looks like mounted.

The Nikon F-mount works like it does on every other camera that uses it. A lens release button is near the 3 o’clock position around the lens. With the button pressed a counterclockwise twist removes the lens and a clockwise twist reattaches it. The Nikon E2Ns does not use the Ai coupling pin, so non-Ai lenses may be mounted without issue. Below the lens release button is a focus mode switch which toggles between Manual, Single Shot, and Continuous.

The viewfinder is interesting, with a mix of familiar and not so familiar. The most obvious difference between this and other Nikon SLRs is that the viewable image takes on an almost square shape. This is a result of the sensor’s 5:4 aspect ratio, compared to 3:2 from a typical 35mm or DSLR. The shape of the viewable image matches that of the sensor and has 98% coverage which means nearly everything you see in the viewfinder is what will be captured.

The focusing screen is bright and easy to compose images with. It is non-interchangeable however, so you cannot swap it with other screens for the Nikon F4. Above the viewfinder are a series of focus LEDs. A green circle means the image is properly in focus, two yellow arrows indicate focus is too close or too far, and a red X means that focus cannot be obtained. An additional LED for exposure compensation will light up if that feature is being used.

Below the viewfinder is a green backlit LCD which shows all of the information you’d expect to see on a modern film or DSLR. It is large and very easy to see while wearing prescription glasses. On this camera, the LCD was brighter near the edges than the middle. I assume this is due to age and not how it would have always been.

The Nikon E2Ns is a camera that is equal parts strange and familiar. Considering it’s age, it is surprising at how close it is to what we would come to expect of DSLRs in the decade to come. On the other hand, for every piece of familiarity, it is difficult to ignore the camera’s bulbous size and thick body. While I always prefer optical viewfinders over rear LCDs, to not have a screen at all to review my images or scroll through the camera’s settings is strange. The 5:4 viewfinder is not difficult to use, but is a reminder that this isn’t a typical camera every single time you put it up to your eye.

I’ve rambled on quite a bit regarding the camera’s history, design, and controls, but what kinds of images can it make and what is it like to use? Keep reading…

My Results

My experiences with both the Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n from 2004 and the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro from 2000 taught me that the farther you go back with early digital cameras, the more difficult it is to work with the digital files on a modern PC. Although the E2Ns is only four years older than the FinePix S1 Pro, those four years were a period of incredible growth. Comparing a digital camera from 1996 to one from 2000 would like be like comparing a film camera from 1940 to 1980 so I was prepared for some challenges.

For starters, I had no way of reading either of the two 40 MB PC Cards that came with the camera. I went online and looked to buy a USB adapter that I could use with my Windows 10 computer, but found that a PC Card to CF card adapter was a more economical option. I found one such adapter that even included a 512 MB CF card for about $15 on Amazon, so I ordered that. I already had a CF card reader so I could just read the card on my desktop PC.

I’ve learned from experience that even with compatible media, sometimes using something too modern on an older device causes issues, as early digital cameras were from an era where flash cards had much less capacity. The camera’s manual repeatedly refers to a Nikon Image Memory Card EC-15 of unknown capacity for use in the camera. On page 85 of the camera’s manual, it states that other cards can be used, and lists some very basic requirements, but does not list specific brands, models, or maximum capacities. When this camera came to me, it included two 40 MB cards by a company called “Newer Technology” so I knew the camera would work with some third party cards, but I had no idea of which ones.

If I knew the Nikon E2Ns worked with a card with 40 MB of storage, it likely would have trouble if I loaded in a 2 GB card, so I went with the 512 MB card as it was the smallest one available. I figured if that didn’t work, I could probably find a used card on eBay.

I also anticipated problems with formatting. I’ve read stores about other 1990s DSLRs in which the file system on the storage cards was different from modern FAT-Ext or NTFS file systems. On one type of an early Minolta DSLR, the file system requires the card to be formatted using the software which was originally included with the camera, and no longer runs on modern Windows PCs. If the Nikon E2Ns were to have a similar requirement, I would be out of luck.

To my amazement, when the PC Card to CF adapter and 512MB CF card arrived, I inserted both into the camera and it detected the storage without issue and immediately worked! No initialization was required whatsoever, and the camera seemed to be okay with 512MB of storage.

After confirming the camera was reading the flash card I had installed, I powered it up using the Nikon ES-1 AC adapter that Paul included and took a few quick test shots around my office. After firing off about a dozen or so, I powered off the camera, ejected the PC Card adapter, removed the CF card and inserted it into my card reader. I browsed to the folder and found twelve 2,511 KB TIF files, but sadly, the built in Windows image viewer couldn’t open the files. I tried opening them with Adobe Photoshop CC and got nothing there either. Looking online for contemporary reviews of the Nikon E2Ns, it references using a Nikon Image Viewing software that likely came included with the camera. A more elaborate Google search returned no other suggestions, and I couldn’t find the software online so I gave up.

The Nikon E-Series does not offer any type of RAW mode, but does support JPG images, so I changed the Image Quality setting from Hi to Fine which tells the camera to write JPG files instead of TIF. I could not find any setting to tell the camera to write both TIF and JPG files at the same time, like you’d see on a more modern camera. After making this change and firing off another dozen or so test shots, I had images!

Since I had to use the camera plugged into an AC outlet, I found my options were limited in my house, so I dug out an old DC -> AC inverter that plugged into my car’s cigarette lighter and plugged the ES-1 adapter into it, so I could shoot the camera from my car. Thankfully the power cord on the ES-1 is quite long, so it gave me enough range to step outside of my car and take some shots with it still plugged in.

I usually start this section of reviews on cameras with Nikkor lenses with the usual, “Nikkor lenses were some of the best ever made and images from them will always look great…” but for this review, I can honestly say that despite what I know is an excellent lens, the Nikon E2Ns cannot come anywhere close to doing the lens any justice. The state of digital sensors at the time this camera was out could not resolve the detail or capture the sharpness these lenses are capable of. While I believe the 50mm f/1.8 AF Nikkor I had attached is a fantastic lens as I’ve used it on many other cameras before, my analysis of the images has almost nothing to do with the lens.

In fact, one anomaly that’s present in almost every image, but especially the outdoor ones is extreme vignetting in the corners. On a normal camera, this could suggest an imperfect lens, but knowing this lens does not vignette, I can only conclude the dark corners are a result of the light path through the Reduction Optical System.

Lens Compatibility: After writing the above paragraph, but before publishing this article, I spotted a page in the camera’s user manual that has a list of compatible lenses, and it specifically calls out some lenses for having shadows in the corners and the 50mm f/1.8 AF Nikkor is one of them. Apparently f/1.4 AF Nikkors are fine, as are manual focus 50mm f/1.2 lenses, but not the f/1.8 or slower lenses.

Critiquing the images, I’ll start with the good. Adjusting my expectations for what a filmless camera from 1996 could do, the images look pretty good. My very first digital camera was a cheap point and shoot that I bought in 2001, and it’s images didn’t look any better than this.

Making 4×6 or even 5×7 prints from these images would likely provide an acceptable print quality. For the professional photographer whose images would be shrunk down for use in a magazine or newspaper, the speed and convenience of not having to develop film was likely a game changer. Looking at a typical newspaper, images are often grayscaled and printed at a resolution where even a 1.3 megapixel image would have sufficient detail.

The auto exposure and auto focus of the camera performed well, as I had no issues getting images in focus and exposed properly. In the images of the bourbon bottles and turntable, I had the Nikkor 50mm f/1.8 at minimum focus. The auto focus system had no problem with the mirror selfies, which is an area that many autofocus cameras struggle with. It should come as no surprise that these parts of the E2Ns performed well as both systems came from the Nikon F4.

Handling the camera was…interesting. Ergonomically, everything worked well. The right hand grip was comfortable and the shutter release was exactly where I expected it to be. I found it a tad annoying that I had to press the mode lock button every time I wanted to turn the camera on or off, but that’s a minor nitpick. Since I kept the camera in auto everything for all these images, I didn’t spend a ton of time going through the settings, but when I did, I thought the command dial worked well. Unlike later DSLRs, the E2Ns doesn’t have a complex menu system with dozens of options. It’s all pretty basic here. Without a doubt, the biggest usability issues come from it’s size. This is a heavy camera, and it’s awkward dimensions make it difficult to take in and out of a bag, and even setting the camera down was a challenge as it constantly wanted to fall over.

As you might expect, 1.3 megapixel images from a more than quarter century old digital camera are going to have some limitations. Resolution aside, things like color saturation and accuracy, sharpness, noise, and exposure latitude are not anywhere close to even the cheapest point and shoots of the late 2000s. I was unable to test the uncompressed TIF images from the E2Ns, but the JPGs from the highest setting often show blown out highlights and muddy shadows in the same image. Although I made an attempt to adjust levels in post processing, there was little I could do to tame highs or pull out detail from the darker areas. Digital has always had a limitation in latitude, but on this camera, it is extreme.

Sharpness was also not what I had expected. Every image, even those I am certain focused correctly seemed soft, even at 1.3 megapixels. If I were to take an image from my smartphone and downscale it to the same 1280×1024 dimensions as these, sharpness would be higher. Since we know the AF Nikkor can resolve a ton of detail, my only conclusion is that perhaps the reduction options are softening things up a bit. To take a full frame image and reduce it to a 2/3″ sensor, something has to suffer, and sharpness is it.

The colors from the camera were very muted and often took on a magenta hue. I did play with the camera’s limited white balance options, and although most of these were shot in Auto, I did try some in the other modes and found no improvement. I wish I had this camera during the spring when I could test it on some colorful flowers, but each of the images I shot all seemed to be lacking in vibrancy and saturation, and any attempt to adjust those in post didn’t help much.

In addition to lackluster color, the images were predictably noisy, even at the ISO 800 setting. Color noise has long plagued all digital cameras, even ones sold today. Small sensors have small pixels and they struggle in low light so I definitely cannot fault the camera here, but I can’t help but wonder what a lower ISO option might have looked like.

I did try a few at the ISO 3200 setting and they were even noisier, but to be honest, no worse than an equivalent ISO 3200 setting on a cheap point and shoot. In fact, I would say that regarding both the color accuracy and noise issues, if you convert these images to black and white, they look pretty decent, and more than usable for a black and white newspaper. The color image below was shot using the ISO 3200 setting and then grayscaled in Photoshop CC.

Despite what at first appears to be underwhelming images with a longer list of cons than pros, as I’ve let a few weeks go by since shooting the camera and writing this section of the review, I can’t help but be impressed at what Nikon and Fuji were able to accomplish with this camera in the mid 1990s. Problems that we still aim to solve today such as crop sensor vs full frame was addressed in a creative way with the Reduction Optics System. Despite lacking modern conveniences like a rear LCD screen, all the other usual controls such as White Balance, Image Quality, and Sensitivity are all here. There is nothing that I’ve ever needed to make a good image on a modern digital camera that the E2Ns doesn’t have.

Sure, it does things in a more rudimentary way, and the resulting images have some serious compromises, but overall, that a 27 year old digital camera can do as good of a job as this one did, is remarkable.

I don’t know who would spend the equivalent of the price of a new car for a camera in 1996, especially considering significantly improved digital cameras like the D1 were barely 2 years away, I have to wonder if early adopters of these cameras had some buyer’s remorse, or was being on such a cutting edge of technology worth the price.

Although these cameras don’t sell today for anywhere near what they originally went for, there is demand for early digital cameras like this, so if you want to add an E2Ns to your collection, prices can be pretty high, especially for a complete camera with charger, AC adapter, lenses, and original paperwork. Be prepared to open your wallet, but if you do, you can at least tell your friends you have one of the most unique and historically significant digital cameras ever made.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_E_series

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Nikon_E2/E3

http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/companies/nikon/htmls/models/digitalSLRs/E2NE2Ns/index.htm

https://www.digitalkameramuseum.de/en/cameras/item/nikon-e2ns (in German)

I wonder if the magenta hue is due to a lack of infrared filtration. It would be great if you could test it with a hot mirror filter on the lens!