This is a Nikon S2, a 35mm rangefinder made by Nippon Kogaku of Tokyo, Japan. The S2 was a significant upgrade to the original Nikon S rangefinder from 1948 and was made between the years 1955 and 1957 when it was replaced by the Nikon SP. By the time the original Nikon S was released, Nippon Kogaku was already an established lens maker, but the S-series was their first attempt at building their own camera, and the only rangefinders the company would ever make. The Nikon S series was designed to take the best of the Zeiss-Ikon Contax and the Leitz Leica, and make one single high quality Japanese built rangefinder. They were successful as the Nikon S-series helped turn the tide in the Japan vs Germany camera wars of the 1950s and would allow Nippon Kogaku to go on to become one of the world’s most successful camera companies.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/1.4 Nippon Kogaku Nikkor-S coated 7-elements

Lens Mount: Nikon S-mount Bayonet (modified Contax mount)

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder with 50mm Projected Frame Lines

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: none

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Hotshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Manual: http://www.nikonweb.com/s2/nikon_s2_manual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Nikon S2 needs no introduction. It was the middle model in Nippon Kogaku’s line up of rangefinder cameras. Although later models would be produced with more advanced features, the S2 is unique in that it has a simpler viewfinder that is actually larger and brighter than later S-series models, yet is still new enough that it still has modern conveniences such as a wind lever, flash sync, and a full selection of shutter speeds. Nikon rangefinders directly competed with the Leica M-series of the same period, so it’s only natural to compare them today which I won’t do. There are some things the Nikon does better and some the Leica does, but they’re both excellent cameras. Considering cameras like the Nikon S2 fetch far lower prices on the used market today, they are an incredible value as one of the best 35mm cameras ever made. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for indescribable cool factor, the complete package | ||||||

| Final Score | 16.6 | ||||||

History

The Nikon S2 rangefinder was produced by Nippon Kogaku K.K. of Tokyo, Japan between the years of 1955 through 1957. It was part of a larger Nikon S-series that started with the Nikon I in 1948 and continued until the early 1960s.

The name Nippon Kogaku K.K. loosely translates to Japanese Optics Company, and it was founded on July 25, 1917 after the Japanese military had ordered three smaller Japanese companies to design a new periscope to be fitted to their new Mitsubishi submarine.

Rather than work separately, the three companies merged together to combine forces and make one single Japanese company. The Japanese government had been going through a period known as the Meiji Restoration in which the government had decreed that Japan needed to be less reliant on imported goods from other countries.

Prior to 1917, the Japanese military had largely relied on exported binoculars, scopes, and other optical products from Germany and the incorporation of Nippon Kogaku was intended to bring an end to Japanese reliance on German optical products. The founding of Nippon Kogaku in 1917 came at the perfect time, as World War I had just broke out, and Japan lost it’s ability to get imported goods from Europe.

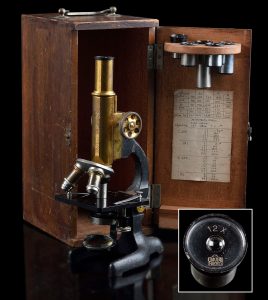

After the merger, the three factories that comprised the three original companies continued to operate making specialized equipment for the Japanese Imperial Navy, the Japanese Army, and other scientific and industrial companies. Nippon Kogaku had over 200 employees, many of which had years of experience in producing lenses, microscopes, rangefinders, and other optical apparatuses.

Perhaps sensing a need for German expertise, in 1921, eight German engineers were hired by Nippon Kogaku with a contract to last no less than 5 years. Of the eight Germans, the two most significant were Heinrich Acht who was principal engineer of product design, and Professor Max Lange, who was in charge of optical lens design. Not much is known about where each of these eight German engineers might have been employed prior to coming to Japan, but the unemployment rate in Germany was very high after World War I, so it was likely not difficult to convince them to relocate to Japan and work for an otherwise unproven optics company. After the expiration of the original 5 year contract, Heinrich Acht would remain employed by Nippon Kogaku for another 3 years.

During their stay in Japan, the eight German engineers helped expand Nippon Kogaku’s product portfolio to include telescopes, binoculars, and aerial photographic lenses. Their first photographic lens was a direct copy of the 4-element Zeiss Tessar lens called the Anytar. The Anytar’s design was overseen almost exclusively by Heinrich Acht during his stay in Japan. After his departure, the Anytar continued to be refined, until eventually reaching or even exceeding the quality of the Tessar it was based off. The Anytar lens was only made in pre-production form and never sold to the public. The only known copies are in the Nikon Museum in Japan.

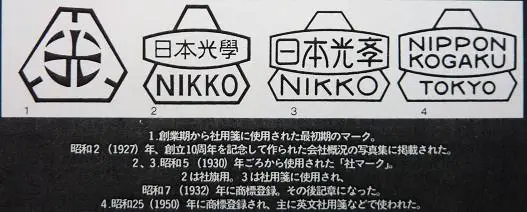

Prior to World War II, the majority of Nippon Kogaku’s manufacturing was for the Imperial Japanese Navy. They did have limited production of microscopes for private consumption outside of the military, however. The earliest products made by Nippon Kogaku were labeled with the name ‘JOICO’ which is an abbreviation for Japan Optical Industry Co., which is a literal translation for Nippon Kogaku K. K.

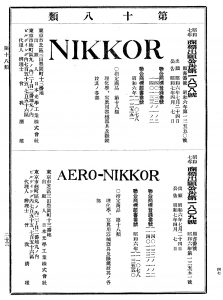

By 1930, the trademark “Nikko” would start to appear on microscopes, and in 1932, the name “Nikkor” was selected for the company’s lenses. To the right is a trademark application for the names “Nikkor” and “Aero-Nikkor” dated July 24, 1931. These trademarks were published on April 7, 1932 officially allowing Nippon Kogaku to use the Nikkor name for the first time.

Ironically, Nippon Kogaku’s first foray into consumer camera design was while working in cooperation with another Japanese company called Seiki Kogaku, or Precision Optics Company in English, who would later become Nikon’s biggest rival, Canon. In those days, Japanese industry worked for the benefit of the Empire, so competing companies would often partner together to accomplish a task with greater expertise and efficiency than a single company might have been capable of.

Seiki Kogaku was founded in 1933 by a modest repair technician named Goro Yoshida, Yoshida’s brother-in-law Saburo Uchida, and a third man named Takeo Maeda with a goal of building Japan’s first compact 35mm camera. Although Seiki Kogaku had the necessary technology and expertise to design the body and shutter to German specifications, they lacked the expertise in optics design, something Nippon Kogaku was great at. As a result, the two companies worked together to release the first Japanese built 35mm rangefinder, and it came with a Nippon Kogaku lens.

This new camera was called the Kwanon, and was never sold to the public. By the time it was ready for civilian consumption in 1936, it’s name had changed to the Hansa (or Standard) Canon. In manufacturing the Hansa Canon, Seiki Kogaku was responsible for the main body including the focal-plane-shutter, the rangefinder cover, and the assembly of the camera body, and Nippon Kogaku was responsible for the lens, the lens mount, the optical system of the viewfinder and rangefinder mechanism.

Seiki Kogaku would exclusively use Nippon Kogaku lenses until 1939, when they would finally start to produce their own designs. The first was the Seiki Serenar 50mm f/1.5. Although the outbreak of World War II would stall further developments, it is commonly believed that Nippon Kogaku would still maintain it’s lens making partnership with Seiki Kogaku until at least 1947.

Prior to the war, Nippon Kogaku was first and foremost an optics company, not a camera company. This did not stop them from working with other Japanese companies on specialized military camera designs that were used by the Japanese Navy and Air Force. None of these designs were ever sold to the public, and very little is known about them.

During World War II, Nippon Kogaku played an instrumental role in the design and development of aerial lenses and cameras. New models such as the Army Aero Camera Mark 1 were produced as late as 1944 during the later parts of the war. Aero-Nikkors were the most commonly used aerial lenses with focal lengths as long as 50 cm. An article published by the Nikon Historical Society in 2001 says that in 1945, at the end of the war, a factory in Ohi was filled with completed 2000 mm Aerial-Nikkors that were ready for the army, but never used.

After Japan’s surrender in August 1945, American forces would shut down most of Nippon Kogaku’s factories. Some sources say that there were anywhere between 19 and 26 factories in total. Regardless of the number, during the period of American occupation in Japan, all military and weapons related manufacturing was prohibited. Nearly all of Nippon Kogaku’s work force became unemployed and the factories sat idle while the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) examined future potential for the company’s resources.

Up until this point, Nippon Kogaku exclusively produced products for the Japanese military. With the sole exception of it’s partnership making lenses for the Hansa Canon, Nippon Kogaku had absolutely no experience producing and marketing designs for the civilian market. Despite this lack of experience, in the days after Japan’s surrender, the company’s many skilled workers were asked to come up with a list of viable products the company could make and sell.

The first product to resume production was a line of quality binoculars that Nippon Kogaku had made during the war. These binoculars were superior to other designs used by the American military, and upon capture of Japanese war ships, became highly sought after trophies for soldiers. Nippon Kogaku’s binoculars were seen as world class products, so it made sense to resume production on a commercialized version of these binoculars.

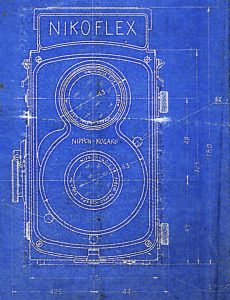

In total, a list of 38 products were selected as viable designs that could be made and sold. A variety of camera lenses, binoculars, telescopes, microscopes, spectrographs, and even cameras would soon roll out of Nippon Kogaku factories. In April 1946, Nippon Kogaku announced the development of two new camera designs, the first was an 80mm Twin Lens Reflex camera called the Nikoflex that was said to have an automatic film advance, a high quality leaf shutter, and Nippon Kogaku’s best Nikkor lenses. The best leaf shutters in the world were all made in Germany, which was also devastated after the war, so Nippon Kogaku set out to design their own leaf shutter, but it was decided quickly that such an undertaking would be prohibitively expensive. Only a few Nikoflex prototypes were ever built, and none are known to survive. Instead, the company decided to focus all of it’s efforts on a compact 35mm rangefinder with an interchangeable lens mount.

During the summer of 1946, Nippon Kogaku worked tirelessly on their new 35mm compact rangefinder. It went through several name changes, one of which was the Nikkorette, but in September 1946 when the first prototypes were produced, the name Nikon was chosen instead as a shortened version of the company’s name.

Not content to follow in the footsteps of Canon and design yet another Leica inspired rangefinder, Nippon Kogaku instead used both the Zeiss-Ikon Contax II rangefinder and the Leica II as the basis for their new camera. It is said that Nippon Kogaku thought that neither the Contax or the Leica were perfect, and decided to take the best of both cameras and make their own. The new Nikon camera would share a lot of cosmetic similarities to the Contax, including the top focus wheel, removable film back, and a slightly modified bayonet lens mount. Nippon Kogaku chose the bayonet mount instead of the Leica’s screw mount as it was faster to attach and detach, but also offered a more secure connection to the camera.

An interesting note about the Nikon rangefinder’s lens mount is that although the mount itself is identical to the mount used on the Contax rangefinder, Contax lenses themselves were not compatible. The reason for this is explained nicely on Stephen Gandy’s Camera Quest site. I’ll try to summarize the info he already has on his site. If however, you would like an even more technical explanation, I recommend this article by Henry Scherer at zeisscamera.com.

During development of the Nikon rangefinder, Nippon Kogaku already had over a decade of experience making Leica screw mount lenses. Going back to the 1930s when Nippon Kogaku had developed it’s first commercial lenses for the Hansa Canon (which was a copy of the Leica II), all of Nippon Kogaku’s lens formulas were designed to Leica specifications.

Edit 2/19/2018: After posting this review, I was contacted by Wes Loder, author of the book “The Nikon Camera in America, 1946-1953” who corrected some of the facts that I originally posted below.

Wes states that the difference between the Nikon and Contax mount lenses have less to do with the nominal focal length, and more to do with the pitch of the internal focusing helicoid. Below is Wes’s exact text to me clarifying why Contax lenses on a Nikon rangefinder are only accurate at infinity:

Scherer’s article on the differences between the Nikon S mount and the Contax mount also must be taken with a grain of salt. The mounts both have the same flange to focal plane distance. Any Zeiss or Nikkor lenses should produce sharp results when set at infinity. The difference lies in the pitch of the internal focusing helicoid. The Contax rotates 274 degrees to move from infinity to three feet. The Nikon only rotates 270 degrees for the same range. That’s what causes the problem. I will not get into whether this difference was due to supposed differences in focal length of the normal lenses or not.

Leica lenses have a nominal focal length of 51.8mm compared to the Contax’s nominal focal length of 50mm. In order for Nippon Kogaku to make lenses to match the Contax’s specifications would have required an alternate lens formula for every lens they made. Since the Nikon rangefinder had not yet established itself as a success, Nippon Kogaku decided to stick with their existing Leica based lens formulas, and give them a Contax mount for the Nikon camera. This way, if the Nikon rangefinder was a failure, they could continue with established Leica mount lenses. As a side note, this proved to benefit Nippon Kogaku during the Korean War, as the first war photographers to discover the Nikon rangefinder were able to easily adapt Nikkor lenses to Leica cameras by modifying the mount.

The difference between a genuine Contax mount lens and a Nikon rangefinder lens is that at infinity, the focal point onto the film plane is identical. As you change focus to something closer, a margin of error is introduced that gets worse the closer you get. This means that although you could attach a true Contax mount lens to a Nikon rangefinder, only images shot at infinity would be correctly in focus.

This margin of error gets worse on telephoto lenses, but is lessened on wide angle lenses, so as a result, many people have found that with lenses like the Zeiss Biogon 21mm and 35mm, or the Soviet Jupiter 12, the margin of error is still within the acceptable depth of field of the lens, especially when stopped down. You can successfully use these Contax mount lenses on a Nikon rangefinder at most normal distances with the iris set to f/5.6 or smaller.

From Leica, the Nikon would share it’s simpler rangefinder and shutter designs. Rather than the vertically traveling “garage door” focal plane shutter of the Contax, the Leica’s horizontally traveling cloth shutter was chosen to both keep costs down and to improve reliability of the camera.

Although the initial design for Nikon’s new camera was completed in the fall of 1946, Nippon Kogaku would wait until March of 1948 to officially offer it for sale. Despite being very well built and innovative in design, the original Nikon (now known as the Nikon I by collectors) did not sell well.

Edit 2/19/2018: Once again, the following information was submitted to me by Nikon historian, Wes Loder regarding the Nikon I:

During the Occupation, it was illegal to sell cameras domestically without special permission. Japan needed cash desperately and exports were the only way to get them. Of the 505 Nikon I’s actually sold, all but 9 exported. The supposed “Ban” on the sales on 24×32 format cameras related only to sales to the military exchange stores. I covered this in depth in an article in the Nikon Journal in September 2015, as well as in my book.

It is estimated that only 738 were ever made. The popular theory of the lack of success of this first model was the camera’s 24mm x 32mm exposure size, which was smaller than the 24mm x 36mm exposure made by most other 35mm cameras. It is said the head of SCAP, General MacArthur prohibited the export of the original Nikon as it would not be compatible with Kodachrome slides which were very popular at the time.

The original Nikon was sold for just over a year, and in late 1949, the Nikon M would be released which would increase the exposed image to a (still not standard) 24mm x 34mm frame. Despite this, the M sold a bit better than the original model in Japan, but the Nikon rangefinder still had yet to garner any attention outside of it’s home country.

It wasn’t until the midst of the Korean War when American press photographers caught wind of a new Japanese camera that had superior optics and build quality to the German cameras, that the Nikon was known outside of Japan.

A story from the June 1951 issue of Modern Photography involves an American named Horace Bristol, who while visiting Tokyo in 1950 came across some 35mm negatives that he thought were sharper and more clearly defined than any he had seen before. He asked which camera made these negatives and was shown a Nikon rangefinder. Bristol was said to be so impressed with the quality of the camera that he bought one for himself. Shortly after, three Life Magazine photographers who had been covering the Korean War, met up with Bristol and saw his Nikon rangefinder. One of these photographers was famed war photographer David Douglas Duncan who was so impressed with the sharpness and detail in the Nikon slides, that he had a Nikkor lens adapted to his Leica and would primarily shoot with this combination throughout the rest of the war.

Upon reporting back to the Life home office about this new superior Japanese camera, the magazine ordered some cameras to be tested by optical experts who confirmed that both the cameras and lenses were of superior quality to anything made by anyone else. As a result, the Nikon rangefinder and it’s lenses became popular with all Life photographers and their reputation quickly spread throughout the United States and the rest of the world.

In December 1954, Nippon Kogaku would release a significantly improved model called the S2. Nippon Kogaku demonstrated their ability to not only innovate, but also to listen to the demands of professional photographers. The S2 was 22% lighter than the original S while maintaining it’s excellent build quality. It also increased the size of the exposed images to 24mm x 36mm, matching the standard set forth by German makers such as Leitz and Kodak AG.

Other new or changed features of the S2 were:

- A larger rangefinder and 100% life size viewfinder allowing photographers to shoot with both eyes open. The S2’s viewfinder uses glass prisms instead of mirrors and has the largest 50mm viewfinder image of any Nikon rangefinder. It also received improved baffles that are less prone to flare than later models. As a result, S2s typically have the brightest viewfinders today of any S-series camera, including the later versions.

- Lever film advance and folding rewind knobs, making film advance and rewind much faster than knobs of the original model.

- Faster 1/1000 top shutter speed, compared to 1/500 of the S.

- Single latch film door. This was a change from the dual latches on earlier models, making film changes quicker.

- An ASA film speed reminder dial takes the place where the second latch existed on previous models.

- The shutter was upgraded with ball bearings, allowing for a smoother and more reliable operation.

- Shutter speeds adopted a standard spacing of 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, 30, 60, 125, 250, 500, and 1000. Gone were speeds like 40 and 100.

- Standard PC flash sync terminal.

- A flash hot shoe, which allowed direct flash connections with Nikon flash guns.

- Faster 1/50th electronic flash sync, up from 1/30.

- Adjustable flash sync dial for flash bulbs (M-sync.)

- The film gate and tripod mount were both built into the main body, rather than add on pieces, which helped to improve body rigidity.

- The film advance and rewind switch has been moved and is integrated around the collar of the shutter release, simplifying the design.

- The leatherette body covering of the S was replaced by a tougher synthetic material that resists nicks and scratches.

The Nikon S2 was the most popular of all Nikon rangefinders, with an estimated production of over 56,000 units. The camera being reviewed here is an earlier model that had chrome shutter speed and film reminder dials. Somewhere around serial number 6180000, the S2 would receive black dials at these locations. These “Black Dial” S2s are sought after by collectors as they are less common than the chrome dials, so their prices usually are a bit higher in the used market.

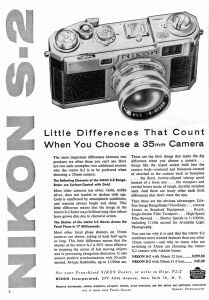

The image to the left from the November 1955 issue of Modern Photography shows the S2 with Nikkor 50/1.4 with a list price of $345, which when adjusted for inflation is $3139 today, placing it right at the level of a modern pro-level DSLR.

Although the Western press was already aware of the earlier Nikon S rangefinder, with the release of the S2, Nippon Kogaku established themselves at the very front of the photographic world. No longer was “Made in Japan” something to be scoffed at, rather it meant something to be admired and respected. In the March 1955 issue of Modern Photography, writer Bob Schwalberg said:

It is inevitable that the Nikon S-2 will be compared against other top-drawer miniatures now on the market or soon to appear, and it deserves to be so compared …. The S-2 is a fast shooting, easily operated, ruggedly designed upper echelon miniature. In picking and choosing among the aristocrats of the 35-mm world, treat the differences between these fine cameras not as differences in quality but in how they operate and how you’ll operate with them. Pick the camera you think you’ll do best with, and you probably will.

The rest of Mr. Schwalberg’s review is in the gallery below.

Despite these advancements, the Germans weren’t sitting idle either, as Leitz had recently released the Leica M3 which was a brand new model designed from the ground up which helped to re-establish Leitz as the standard bearer for professional cameras. The Leica M3 improved upon the screw mount Leicas with some features that Nikon already had, such as a bayonet lens mount, adjustable frame lines in the viewfinder, a coincident image rangefinder, and a single dial shutter selector. The Leica M3 was seen as the pinnacle of rangefinder development up until this point.

Not willing to settle for second best, immediately after releasing the S2, Nippon Kogaku would begin development on what would be called the Nikon SP, which was intended to be the culmination of Nippon Kogaku’s camera development. No expense was spared with this new model. The SP would have a parallax corrected viewfinder with frame lines for up to 6 different focal lengths. It would have an optional motor drive attachment that allowed up to a 3 frames per second shooting speed, making it the first rangefinder with such an option. Later SPs would have a horizontally traveling titanium curtain, improving upon the cloth curtains used by everyone else.

Upon it’s release in 1957, the Nikon SP bested the M3 in several areas, and proved that a Japanese company could meet and in some cases exceed the high quality and innovative standards dominated by the Germans. The SP was aimed at the professional photographer and had a price tag to go with it. Around 32,000 SPs were built, which is pretty spectacular considering the extremely high price of one. It has since been regarded one of the best rangefinder cameras of all time and is currently an extremely sought after model by collectors. In 2005, Nikon would re-release the SP as an anniversary model. 2500 were built and sold exclusively in Japan through a lottery system. The price was 690,000 yen, which was equivalent to nearly $8000 USD at the time.

Nippon Kogaku developed a new Single Lens Reflex camera at the same time as the Nikon SP. That camera would be released in 1959 and would become the Nikon F, which would change the face of not only the camera industry, but would signal a new era of dominance of Japanese manufacturing. Nippon Kogaku realized that with the release of the SP and the Leica M3, that rangefinder design was nearing the pinnacle of design and technology. They felt it was unlikely that there was much more that could be done to significantly improve the design, but that there was much more potential in the SLR market.

Before completely abandoning the rangefinder altogether, Nippon Kogaku would release two more models in the S-series, the S3 and S4. Both new models would both be simplified versions of the SP to reduce cost. The S3 had a revised viewfinder that lacked automatic parallax correction, and had fixed framelines. The S4 would further reduce the feature set, omitting the 35mm frameline, leaving only the 50mm and 105mm in the viewfinder. The titanium shutter curtain of the SP and S3 would be replaced with one made of cloth, and it would lose the provision for motor drive on base of the camera.

Beyond the S3 and S4, Nippon Kogaku would work on at least two more rangefinder models, neither of which were ever released. The first was an updated SP called the SP2 which featured a zoomable viewfinder, more advanced parallax correction, and a redesigned folding rewind crank. SP2s exist that are nearly production ready and may have been given to photographers as test models, although none were ever sold to the general public. The other was an ambitious model called the SPX which featured a TTL exposure meter, and the Nikon F SLR’s bayonet mount. The SPX never made it past the prototype stage, and the only known example can be found in Nikon’s museum in Tokyo, Japan.

Although Nippon Kogaku’s decision to focus entirely on the Nikon F SLR meant that it would no longer compete in the rangefinder market, the Nikon S-series cameras remained hugely popular with professional and hobbyist photographers well into the 1970s.

Today, all models of the Nikon S-series are extremely collectible both as display pieces and shooters. Nippon Kogaku built the S-series to an incredibly high standard for quality and although they are not impervious to the ravages of time, when working, are still extremely capable cameras today well over half a century after they were made.

Prices for S-series models range from high to even higher! The biggest values are in the original S and S2 models, with S3 and SP models fetching the highest prices since they were the most advanced and had the biggest feature sets. The original variants like the I and M are also highly sought after for their rarity, but no matter which model you are after, you’ll generally need to open up your wallet quite a bit if you want to add a good working example to your collection.

My Thoughts

In my time writing reviews for this site, I have tried to stay true to the concept that I don’t duplicate too much information that’s already out there. Sure, many of the historical or factual parts of my reviews have taken bits and pieces from other reviews or articles about a particular model, but when it comes to what I have to say about a camera, I am less interested in reviewing a model that a large number of people already know a lot about. This is the primary reason why as of December 2017 there still are no reviews on my site for cameras like the Canon AE1 or Pentax K1000.

When I reviewed the Leica M3, I realized that I was on the verge of violating this self-imposed rule that I have by discussing a model that a great deal of information already exists online. In an effort to keep the review interesting, I solicited thoughts from a group of collectors in the Vintage Camera Collectors group on Facebook. I asked members who had first-hand knowledge of the M3 to talk about what they liked and what they didn’t and I cherry picked the best comments and put that into the review.

I’m not going to do that again, and I’m also not going to sit here and ramble on about how to use the Nikon S2. If it’s not already clear from the section above that this was a world-class camera developed by a company who was already well on their way to being one of the most successful companies in the photographic industry in the world, with the highest levels of quality, I don’t know that I have the vocabulary to convince you otherwise.

The Nikon S2 is a superb camera. Of the 120+ reviews I’ve written thus far on this site, the only one that compares to it is the previously mentioned Leica M3 which I borrowed from my neighbor. I own this S2, so I can say that this is my favorite camera in my collection. Why, do you ask?

For one, I love the way it looks. There is no part of this camera that isn’t purposeful, yet it never takes a function over form aesthetic. Whether this was intentional or not, the designers who created this camera managed to make an effective photographic tool that looks great too. You’re probably thinking, “wasn’t the Nikon S-series heavily based on the Zeiss Contax, so shouldn’t Zeiss get the credit for it’s design?” Maybe a little, but not as much as you’d think. The Nikon S series certainly shares some design similarities with the German Zeiss rangefinder, but the two really don’t look that much alike.

The most obvious cosmetic difference is in the position of the viewfinder windows. Nippon Kogaku borrowed the rangefinder design from Leica rather than the long base on the Contax. While technically a longer base rangefinder allows for more accurate measurement, I’ve never once heard of anyone complain about a lack of accuracy of any Leica rangefinder. The shorter rangefinder base not only looks better, but it lacks a common frustration of Contax rangefinders (and their Soviet copies, the Kiev) in that your right hand can easily get in the way of the rangefinder window, necessitating a contortion of your right hand while holding the camera to your eye.

There are many other cosmetic differences between the two. The most notable is the Nikon lacks a self-timer like the Contax had, and most of it’s controls are in different locations. It is ever so slightly taller, and with a stepped top plate. The lens mount on the Nikon is rotated about 90 degrees from the Contax. You can clearly see this in the position of the little pin that engages when the focus locks. On the Contax, its at the 2 o’clock position around the lens, and on the Nikon, its at the 10 o’clock position.

I simply adore the way the Nikon S2 looks. It doesn’t look like many other cameras out there. Leitz was so successful at making the screw mount and M-series Leicas, yet so many people copied them, that its refreshing when I see a Nikon S-series. As a collector, every time I see a camera that looks like a screw mount Leica, you have to stare at it and think, is that a Soviet copy, or a Canon, or a Nicca, or a Reid? Although no one really cloned the M-series, there are a number of others that at a distance look close. Aires, Voigtländer, and even Leica themselves have made models that look “sorta” like the M3. When you see a Nikon S-series, you immediately know what it is, as nothing else quite looks like it.

I am sure those of you reading this can grant me a certain leeway in my praise for the cosmetics of the S2 since beauty is always in the eye of the beholder. But how will my praise stack up when it gets to the performance of the camera?

I’ll admit, the Leica M3 is a fine piece of machinery. I would be a liar if I said I didn’t want one in my collection, and I’ll even admit that there are ways in which the M3 beats the S2. To be fully fair though, if we’re going to put these two cameras head to head, the Nikon SP was more of a direct competitor to the M3 than the S2 was, but I can only talk about what I have access to.

The weight, the tactile controls, buttons, knobs, and switches are all top notch. Everything about the S2 is comparable to the best that Germany could offer. The M3 has the biggest and brightest coincident image rangefinder I’ve ever seen on a camera. It also has all of it’s shutter speeds on one dial. The S2 is a bit more vintage in this regard. Later S2s came with black dials that some collectors value over the silver dials like mine has, but looking at pictures of both, I prefer the silver dialed ones. It gives a consistency to the top plate that just looks better to me. The hi/low shutter speeds of the S2 don’t bother me at all. For one, I rarely use anything slower than 1/30, but even when I do, I like Nikon’s implementation of it. Turn both the hi and low speeds so that 30 lines up and then you are free to change the slow speeds down all the way to 1 second. The S2’s shutter speed dial rotates while cocking the shutter, but unlike many cameras with two piece shutter speed dials, the speed can be safely set regardless if the shutter is cocked or not.

Back to the viewfinder. As long as you don’t compare the viewfinder of the S2 to the M3, it is very good. Better in fact, than most coincident image rangefinders that would come out decades later. The full 50mm frame is represented with nearly the entire image seen through the viewfinder. The projected frame lines extend almost all the way to the edges, making for a very large image. Wearing prescription glasses, I had no problem seeing the full 50mm frame lines in the S2. Sure, they don’t change when changing lenses, but that’s OK. From what I understand, this lack of changeable frame lines, allowed Nippon Kogaku to build the S2’s viewfinder as one large glass prism, allowing it to have the largest and brightest viewfinder of any Nikon S-series camera.

The spec sheet for the S2 says it had upgraded ball bearings in the film advance system, and this was obviously an excellent upgrade as today, 62 years after it was built, the Nikon S2 has one of the smoothest film advances of any camera I’ve ever used. The lever has just the right heft and resistance, that you don’t feel like something is broke internally, yet the smoothness and precision in which is moves inspires confidence that you wont have any torn perforations in the film or strangely spaced exposures. In fact, all of the camera’s controls are this way. What’s even more amazing is that this example in my collection is far from a shelf queen. My camera shows quite a bit of signs of regular use. I believe my camera was well loved and shot many, many rolls of films over it’s lifespan, and despite this regular wear and tear, does not show a single sign of being ready to fail.

Loading film in the camera requires a latch on the bottom of the camera to be turned from Closed to Open and then the entire film back comes off. This was a design element that Nippon Kogaku would carry over to the Nikon F SLR, and although it isn’t as convenient as a hinged door, it is nicer than the bottom loading nature of the M3 and all screw mount Leicas.

With the door removed, the inside of the camera reveals a very modern looking film compartment. Film loads from left to right, and the fixed take up spool rotates clockwise. The take-up spool has only one notch on it, but it’s made of metal, unlike other 1950s rangefinders that had started to make the switch over to plastic.

As for the rest of the camera, the Nikon S-series kept one of the cooler features of the Zeiss Contax, which is the top plate focus control. You can still change the focus of the lens by rotating the lens like any other camera, but you can optionally rotate a knurled wheel that sticks up conveniently located in front of the shutter release. This allows for one handed precision control of the focus. It’s not something I use often, but to give you two different ways to control the focus on this camera is cool.

The Nikkor 50/1.4 lens mounted to this S2 has a 12-blade iris with an aperture ring with click stops from f/1.4 to f/16. The movement of the aperture selector is easy, with each click stop feeling just tight enough to remind you it’s there, but unobtrusive when you need to make large changes in iris size.

Earlier in this article, I mention that although Nippon Kogaku used the physical connection of the Zeiss Contax bayonet mount, the lenses aren’t exactly compatible due to something called ‘nominal focal length’. Basically, this means that although Contax and Nikon S lenses will physically mount, they are only accurate at infinity. As you change focus, a margin of error is introduced that gets worse the closer you try to focus. This margin of error is amplified on longer telephoto lenses, but minimized on shorter wide angle lenses. In my research for this article, I found that the margin of error on a wide angle Contax lens is within the depth of field for most photography to where a wide angle Contax lens is a suitable option for Nikon rangefinders. To test this theory, I picked up a Soviet Jupiter 12 35mm lens and mounted it to my S2 to give me a wide angle option. As of the writing of this review, I have yet to try out the Soviet lens, but once I do, I will be sure to update this review.

The Nikon S2 is a superb camera. There is a reason that these cameras helped propel Nippon Kogaku as a world leader in camera and optics design, and why they are still so sought after today. Sometimes, things have high values as luxury items, but their use doesn’t always live up to their price. That is not the case here. The Nikon S2 may not be cheap, but it’s absolutely worth it.

My Results

Anticipating that the Nikon S2 was something special, I wanted to get as much experience with it as possible before writing this review, so I decided I would shoot 2 rolls of film through it, one in black and white, and one in color. Since I can develop my own black and white at home, I could get instant feedback on the camera and it’s capabilities, and assuming everything was OK, I could proceed with a roll of color that I would send in for developing later. For my first roll, I chose fresh Kodak TMax 100 and shot casual shots around my house in early summer 2017.

The second roll was fresh Fuji 200, shot over the 4th of July holiday when my wife and I went to Milwaukee, Wisconsin for Milwaukee Summerfest.

I was quite impressed with the results from these two rolls. As I expected, the images came out properly in focus and the exposures all seemed correct, suggesting the camera is in good working order, despite showing heavy signs of use.

I have a theory when it comes to shooting old cameras where the ones that look the worst, often perform the best. I’ve come across many mint looking cameras that show barely any signs of use, yet end up having major mechanical or operational woes, whereas heavily used cameras still seem to work correctly. Perhaps it was the years of use that “broke in” the camera and allowed it to keep running as opposed to the shelf queens that suffer the rigors of time without being able to “stretch”.

In a few of the images, especially the one of the crowd at the concert in the color gallery, edge softness is very evident when the lens is shot wide open. People like Ken Rockwell say the Nikkor 50/1.4’s optics are inferior to modern lenses wide open, and he’s not exactly wrong. If you like looking at lab tests of DxOMark charts or static pictures of test patterns, you won’t be impressed, but that’s not where this lens shines. Classic glass like this was never meant to be picked apart on a high resolution computer screen. These lenses were meant to capture real world photographs with real world imperfections, and they do that job quite well. The above 16 images are just a few from the two rolls I shot and I love them all.

This is the only Nikon S2 I’ve ever shot, so I’m not about to make any generalizations about others out there, but if my experience is typical of other S2s still in use, these are fantastic cameras. Sure, I could sit here and pick and choose particular features of the camera that someone has done better, or ways in which a more modern camera might be easier or more convenient to use, but that’s not the point. If you are a fan of classic mechanical cameras, it really doesn’t get much better than this. The Nikon S2 is certainly not the most advanced or even more convenient camera I have, but it very well could be my favorite. It love the style, the controls, the feel, and it’s operation suits my style perfectly.

Nikon S-series rangefinders are not cheap cameras, and there are many people who consider these out of their price range. I know I was one of those people, and while I did spend a little more on this camera than others in my collection, I did get it for an outstanding price because I will willing to take a risk on an “ugly” camera. Nippon Kogaku built the Nikon rangefinders to the highest quality standard, and aside from those who were flat out abused, most should still be usable today. If you’re like me, and you like to actually use your cameras and not stare at them on a shelf, a few nicks and scratches shouldn’t bother you.

If you have an opportunity to pick up one of these wonderful cameras at anywhere near your price range, I say go for it. I love this camera, and of the ones that I own, this is the pinnacle of my collection.

Additional Resources

https://www.cameraquest.com/nfs2al50.htm

http://www.japancamerahunter.com/2012/10/camera-review-nikon-s2-with-nikkor-s-50mm-f1-4/

https://www.casualphotophile.com/2016/09/02/nikon-s2-camera-review/

http://imaging.nikon.com/history/chronicle/rhnc08s2-e/

http://www.stevehuffphoto.com/2013/05/06/holding-the-holy-grail-a-nikon-s2-by-daniel-schaefer/

http://www.photoethnography.com/ClassicCameras/NikonS2.html

http://mir.com.my/rb/photography/companies/nikon/htmls/models/htmls/s2_s4.htm

http://www.nicovandijk.net/rangefinder.htm

http://rangefinderchronicles.blogspot.com/2013/01/my-new-nikon-s2.html

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=11617

You might want to read my book on the early history of the NIkon camera. There are a lot of errors on the NIkon out on the web, particularly Gandys page. I have urged him to revise his page several times but he can’t be bothered. A lot of myths in your page. For example, virtually all the Nikon Is that were sold were exported. Fewer than a dozen were sold domestically. The SCAP ban related to the sale in the military exchange stores.

Anyway, read the book. “The Nikon Camera in America, 1946-1953”

Cheers, Wes Loder

Wes, I would love to correct any factual errors in my article. As you noticed, I got most of it from other articles already online. Is your book somewhere I can read it online?

Thank you for the review – I have a near mint S2 that I have used only a few times in the couple years that I have owned it…time to load a fresh roll.

Another fine review, Mike, and this time about my favorite camera! Glad that you could agree to the changes that Wes suggested. Between him and Rotolini you can’t go wrong.

I’m looking forward to getting back into doing some serious photography now that Nikon Rangefinder Month (March) is coming up. I’ve been slacking off too much lately. It’s a shame to let something like the S2, and the wonderful Nikkors sit around all winter long.

Wes, Great article, and I have a question for you hopefully you can answer. I am doing a documentary on Diane Arbus and it mentions that she used a Nikon 35mm in 1956. Would that have been the S-2? The only photo of her with a 35mm camera is from the side and I can’t see any of the details on it other then an upright oblong sliver rectangle shape (on it’s side). Do you know what kind of camera she used? Also do you know where I can find an inexpensive model like that (it doesn’t have to work I just need it for a prop). Thanks, James

James, thanks for the compliments. If Diane Arbus used a Nikon in ’56 it would have had to have been either an S2 or one of the earlier models. The SP and S3 didn’t come out until a year later!

If you’re looking for a Nikon-esque camera for a prop, the cheapest alternative would be a Soviet Kiev 4. Although they’re not identical both the Kiev and Nikon are based off the original Zeiss Contax rangefinder. The Kiev is almost an exact copy, whereas the Nikon has a number of cosmetic differences that from a distance, a non collector probably wouldn’t notice. Good luck!

Wes, thank you for your response. I will try to find an inexpensive S2 camera to buy or rent from a prop house. .