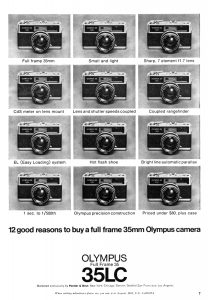

This is an Olympus-35 LC, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Olympus Optical Co., Ltd. from 1967 to 1969. The LC is the predecessor to the very successful Olympus 35 SP, sharing that model’s body and 7-element lens, but without auto exposure or the dual spot/averaging metering system of the SP. The LC’s CdS meter has a coupled match needle readout visible both inside the large and bright viewfinder, and also on the top plate. The Olympus-35 LC is a large and very well built camera with one of the best lenses ever found on a fixed lens rangefinder. It is easy to use and despite it’s large size, has good ergonomics and isn’t terribly heavy.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 42mm f/1.7 Olympus G.Zuiko coated 7-elements in 5-groups

Focus: 2.7 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Copal X Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell w/ top plate and viewfinder match needle

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: Hot Shoe with M and X Flash Sync at all speeds

Weight: 661 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/olympus_pdf/olympus_35_lc.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Olympus-35 LC was the predecessor to the very popular Olympus-35 SP, sharing that camera’s body and excellent G.Zuiko lens. It lacks auto exposure and the SP’s unique dual metering modes, but otherwise shoots the same high quality and sharp images. As an added bonus, this camera sells for a fraction of it’s more popular bigger brother, making for an incredible value. I actually prefer the manual shooting mode of the 35 LC as it still couples to the meter, which the SP does not. If you are looking for a large bodied 1960s Japanese rangefinder with a fully manual shutter and the convenience of a match needle, the Olympus-35 LC is an excellent option! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall excellence, a 7-element lens for a bargain price | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

History

You can’t even begin to dive into the history of Olympus without stumbling upon the name Yoshihisa Maitani a large number of times. His contributions not only to Olympus, but the entire Japanese camera industry are up there with other highly influential greats like Masahiko Fuketa and Kazuo Tashima. But this review is not about anything Maitani created. Despite how it may seem, Olympus created a large number of other rangefinder and SLR cameras without his help.

You can’t even begin to dive into the history of Olympus without stumbling upon the name Yoshihisa Maitani a large number of times. His contributions not only to Olympus, but the entire Japanese camera industry are up there with other highly influential greats like Masahiko Fuketa and Kazuo Tashima. But this review is not about anything Maitani created. Despite how it may seem, Olympus created a large number of other rangefinder and SLR cameras without his help.

After World War II, like most Japanese optics companies, Olympus produced a large variety of folding 6×6 cameras and a couple different Twin Lens Reflex models, all using 120 format roll film. These two styles of cameras were both very popular in Japan, and were easy to export to western countries as they were built to a high level of quality of similar German models, but at a lower price.

By the mid 1950s, companies like Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta), Konishiroku (Konica), and Kuribayashi (Petri) all started to dip their hand into the world of 35mm. Already dominated by a large number of German models and high end rangefinders by Canon, Nicca, and Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), each of these companies tried their hand at mid level fixed lens rangefinders.

In 1955, Olympus’s first 35mm rangefinder model, the 35S made it’s debut with a cleanly designed and attractive body. It was one of the first Japanese cameras to have a film advance lever instead of a knob, and came with one of the company’s good four element D.Zuiko lenses.

Two years later, the 35 S evolved into the 35 S-II which added a bright frame finder, and was the first Olympus camera to come with the company’s seven element G.Zuiko lens. Available in both f/2 and f/1.8 speeds, the Olympus 35 S-II raised the bar for fixed lens rangefinders which would see them competing with a number of other companies like Mamiya, Yashica, and others.

In 1958, Olympus would release a new camera called the Olympus Auto which added a light meter to the same basic body of the S-II, but despite the use of the word ‘auto’ was not yet capable of fully automatic exposure.

That would not happen for another two years when in 1960, the Olympus Auto Eye would be released. Although it was not the first ever auto exposure camera, upon it’s release it was one of the most advanced. Featuring a full range of flash synchronized shutter speeds from 1 – 1/500, a combined coincident image coupled rangefinder with automatic parallax correction, an aperture readout in the viewfinder, and once again the company’s fast seven element G.Zuiko lens, the Olympus Auto Eye was a technological marvel. It would also debut a familiar body design that would be shared in later Olympus rangefinder cameras released over the next decade.

The formula that Olympus used with the Auto Eye would be tweaked throughout the rest of the decade with small revisions in a number of models including the Olympus S and SC Electro Set, the 35 LE, 35 LC, 35 SP, 35 UC, and finally the 35 SPn. All cameras shared a similar body, lens, leaf shutter (the LE would use a simpler 2-blade shutter) and would have some form of metering.

The model being reviewed here, the Olympus-35 LC was released in 1967 and although it lacked automatic exposure, still had a seven element lens, a large and bright viewfinder with a combined coincident image coupled rangefinder with automatic parallax correction, and a CdS exposure meter with match needle read out.

I was unable to find any prices for the camera, but the earlier Olympus-35 LE was priced right at $100, so it stands to reason the 35 LC sold for the same, or a very similar price. If so, that compares to right around $800 today making it a pretty good bargain for someone wanting classic mechanical simplicity with the modern convenience of a light meter and an excellent lens.

Edit 9/1/2022: Thanks to an eagle-eyed reader, the ad to the left clearly states the price of the Olympus 35LC as “under $80” which somehow I missed. This lower price than the previously mentioned 35 LE means that it’s inflation adjusted price compares to around $710 today.

Despite what seemingly looked like it should have been a good seller, the Olympus-35 LC does not appear to have been produced for very long. Some sites online suggest it was produced until 1970, which is possible, but a more likely date would have been 1969 when the 35 SP was released.

In my research for this article, I found very little info about the Olympus-35 LC. Apart from the ad above, I found no reviews, catalogs, or any sort of mention of the model in any US magazine buyer’s guides. I scoured through every single 1967 and 1968 issue of both Modern and Popular Photography looking for any kind of reference to the camera and nothing appeared, not even in either magazine’s year end buyer’s guides. In fact, had it not been for the previous ad above, mentioning that the camera was distributed through Ponder & Best, I might have even guessed the camera was never exported to the United States.

Whatever reason for the relative obscurity of the Olympus-35 LC, I don’t think it had anything to do with it’s quality or capability as a camera. The Olympus-35 LC has an excellent build quality, an awesome lens, great viewfinder, and full manual operation with a reliable CdS exposure meter. As an added bonus, as the “little brother” to the much more popular Olympus 35 SP, the camera can often be found for significantly less than that camera, and as long as you don’t care about auto exposure or spot metering, it’s a fantastic choice.

Today, there are many options for large Japanese rangefinders. Konica, Minolta, Canon, Yashica, and Petri all made models with nearly the same feature set as the Olympus-35 LC, but very few of those have a 7-element lens and the 35 LC’s combination of features.

If you find one of these for sale, there is a very good chance the seller won’t be asking for much, and as long as it appears to be in good condition, is definitely worth picking up.

My Thoughts

I always find it interesting to find models like the Olympus 35 SP that are highly regarded and demand a high price when there might be another very similar model, made by the same company that is otherwise identical save for one or two minor differences.

In the case of the Olympus-35 LC, it shares the same body, the same lens, a similar shutter and viewfinder, yet it demands a fraction of the selling price of the SP. I own a great deal of electronic SLRs that can be switched between spot and average metering and I almost always use average metering. Spot metering can be handy in certain very specific instances, but it’s just not something I use very often, so losing out on that feature is hardly a deal breaker for me. And of course auto exposure is a great feature too, but when it comes to 1960s rangefinders, it’s just not something I expect to use.

So from a value perspective, the LC has everything I would ever want in the SP, but I was able to pick this camera up for about $20 which is a far cry for what SP’s go for.

From the top, the large body of the camera allows for all of the controls to be spaced out with plenty of room to spare. On the left is the folding film rewind knob. In normal operation, the knob sits in a recess, and barely protrudes above the top layer of the place, but a gentle upward tug raises it for easy and fast rewinding.

In the center, beneath the large and bold OLYMPUS-35 LC logo, is a flash hot shoe and match needle readout. Although I rarely use flash with old film cameras, being able to mount a modern electronic flash is a huge plus. Also, the match needle readout is duplicated within the viewfinder for easy operation.

Finally, off to the right is the large film advance lever and automatic resetting exposure counter. From a resting position, the advance lever pulls out about 30 degrees to a ready position, and from there only requires a quick 128 degree motion to fully advance the film, cock the shutter, and advance the additive film counter. The movement of the film advance is very quick, but must be completed in it’s entirety before the shutter can be fired. The Olympus-35 LC does not support multiple short motions, but it hardly needs to.

Flip the camera over and the bottom has the rewind release button, centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket and screw cap for the PX625 battery compartment. Although designed for mercury batteries, my experience with a 1.5v alkaline replacement didn’t seem to negatively affect the meter as it gave agreeable readings in the situations I used it in. Whether or not the camera has a voltage limiting bridge circuit, or I just got lucky, is anyone’s guess.

The back of the camera is pretty bare, save for the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder, and a black button which activates the CdS meter. Under normal operation, the camera’s meter has no power, but upon pressing this button and holding it in, it will make a reading for as long as you hold it down. While I would have appreciated a design in which a single press would activate it and leave it on for 10-15 seconds, it’s location is comfortably located where your right thumb naturally rests anyway, so holding it down is not a chore. Another advantage to the button method is that the meter only drains the battery when it’s activated, so a single battery should last quite a while in the camera.

The Copal-X shutter works similarly to those found in any other leaf shutter rangefinder in which shutter speeds are changed separately from aperture f/stops. Thankfully, the Olympus-35 LC does not use any kind of coupled EV or LV scale, so you are free to choose any combination of speeds or f/stops you wish. With the meter activated, the needle will respond to any change in exposure, and as long as the match needle falls within the two marks on either the top plate or within the viewfinder, proper exposure will be achieved.

Film loading is an uneventful affair. A quick upward tug of the rewind knob, and the right hinged door swings open to reveal the film compartment. Film transport is from left to right onto a fixed and multi-slotted take up spool making film loading a snap.

The film pressure plate on the door is a large piece of painted metal with divots to reduce friction as film passes along it. Along each side of the plate is a roller and metal clip to hold the cassette and film in place to help maintain film flatness. Like most Japanese cameras of this era, the Olympus-35 LC originally came with foam light seals which will have completely degraded on all examples, so replacing them before shooting any film in the camera is essential not only to eliminate light leaks, but prevent foam material from falling into the film gate.

The viewfinder is large and bright, with both a pink tinted medium sized rectangular rangefinder patch and projected frame lines that nicely contrasts with the blue tinted viewfinder and automatically corrects for parallax. Focusing the camera is done by moving a paddle sticking out of the side of the shutter, in each reach of your thumb while supporting the bottom of the camera with your left hand.

At the top of the viewfinder is a match needle readout that is split into three sections. Two larger ovals on either side indicate over and under exposure, and a smaller oval in the center indicates proper exposure. With the meter activated, you select any combination of shutter speed and f/stop that moves the black needle into the smaller oval in the center for proper exposure. There is no other information within the viewfinder to indicate any other setting on the camera. I found the whole viewfinder to be very easy to use, even while wearing prescription glasses.

From the left side of the camera, you can see a PC flash sync port for people wanting to use flashbulb, or some other kind of auxiliary electronic flash. From this angle, you can also see both the focusing paddle on the side of the shutter and a small chrome self timer lever above it, just to the left of the depth of field scale. Although I generally advice against using self timers on older cameras like this, the location of the lever in this position as opposed to the bottom of the camera like on many others, reduces your chance of accidentally activating it.

The Olympus-35 LC is a camera that on paper, looks pretty simple and uninspiring, but in use turns out to be a fantastic camera. Although large, I never found the camera to be uncomfortable for my average sized hands. Each control is in a logical location to where I think someone with smaller hands wouldn’t have an issue. The viewfinder is one of the better ones found in a fixed lens rangefinder, and of course the Olympus G.Zuiko should be capable of some really terrific images. All signs point to this being a fantastic camera, but as I’ve found out a number of times, things don’t always go according to plan, so is the Olympus-35 LC’s obscurity foreshadowing of anything, or is this truly a diamond in the rough?

My Results

Reasonably certain the Olympus-35 LC was in good working order, I took it out on a late winter day in early 2021 with some fresh Kodak TMax 100 in it and went shooting. I enjoy shooting TMax as for me it is the best all around black and white film that I have a large supply of. It doesn’t have quite the fine grain of Pan-X, but with a more flexible 100 speed, means it can be used in a greater deal of lighting situations.

Although many other Japanese camera companies are known for their four to six element rangefinders, there is a much smaller number of companies offering a seven element model and if that extra element is something you’re after, Olympus has the widest selection of models.

Any concerns I mentioned in the earlier section about the 35 LC’s obscurity suggesting that perhaps there might be a reason for that can be put to rest. The G.Zuiko lens delivered extremely crisp and sharp images corner to corner. I saw no vignetting, no edge or corner softness, or other anomalies of any kind associated with lesser lenses. The images above are as good as those shot through the lens of any manufacturer I’ve ever seen. My choice of Kodak TMax 100 and it’s fine T-Grain was a perfect match for the seven element Zuiko.

I found the location of all the controls to be intuitive and without any quirks that might slow me down while shooting. The location of the focusing paddle on the left side of the shutter was in a perfect location for my thumb, and with a total movement from minimum to infinity focus of about 45 degrees, the throw was neither too little or too far. As 35mm rangefinders got more and more compact, the focusing throw kept getting smaller and smaller to where it became difficult to get precise focus as even the slightest movement moved the lens too far.

Normally when writing these reviews, I can find some sort of minor nitpick worth mentioning and as I sit here at my desk, handling the 35 LC, I am struggling to find even the most minor of annoyances. I guess I could fall back on the use of a mercury battery, which by 1967, other companies like Yashica had already started to switch over to silver oxide batteries, but that’s not really fair as mercury batteries were still very common then.

Olympus has a long list of desirable cameras both for shooters and collectors alike. With a range of models including the Pen F and non reflex Pen models, the extremely compact XA, and the long lived and extremely popular Trip 35, it’s hard to find a collector without a favorite model.

When it comes to Olympus’s classic rangefinders (excluding the XA), the most commonly mentioned model is the 35 SP, and for good reason. Featuring an excellent 7-element lens, a very innovative and unique dual CdS meter offering both averaging and spot metering and auto exposure, the SP has a list of features that no other camera had.

Of course, with any highly desirable camera comes high prices, and if you want a 35 SP (or it’s very rare variant the 35 UC), expect to pay a pretty premium for one. Not only that, with a higher reliance on electronics, there is also an increased chance something might be wrong with it. Meters die, batteries corrode, and electronics fail, so finding a nice looking SP still requires you to verify it works.

If you’re on a budget and the primary reason you are looking to pick up the SP is it’s lens, you might be better suited to consider the 35 LC. Without auto exposure or the dual mode metering, the 35 LC has everything else that the SP has, and depending on your perspective, might even be a better camera. Although the SP does offer full manual control over the shutter, the metering system is not coupled in manual mode and doesn’t offer a match needle read out. All you see is an EV number, which you then need to manually choose a matching combination on the lens to get the exposure correct. It works, but is slower than a coupled match needle. If you want to shoot the SP in full manual mode, I think it’s easier just to use Sunny 16 or an external meter. On the LC however, you are free to change whatever combinations of shutter speed and aperture you want and as long as the needle is within the range in the viewfinder, you’ll always get a proper reading.

The Olympus 35 SP is technically more impressive, but with a much higher cost, a higher chance of electrical problems, and crippled manual exposure metering, I feel the 35 LC is a much better option. Looking at these images, I can wholeheartedly declare this camera a winner. If you are first getting into 35mm rangefinders, the Olympus-35 LC is an excellent option and one I highly recommend.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://camerapedia.fandom.com/wiki/Olympus_35_LC

https://cameragocamera.com/2018/03/29/olympus-35-lc/

https://aremac0.tripod.com/Oly35LC.htm

http://randomphoto.blogspot.com/2018/08/a-quick-review-of-olympus-35-lc-camera.html

https://www.rangefinderforum.com/forums/showthread.php?t=133313

https://gears.fotolove.tw/2012/04/olympus-35-lc1967.html (in Chinese)

Another great review of a classic, Mike. I already checked eBay, and of course since this article came out, the prices for this camera are already about what I paid for my 35 SP, lol. Thanks a lot, lol. I have several Olympus classics and love them all, from the earlier 35-SII (which is one of the earlier models with auto parallax correction and a bright viewfinder), to the 35 SP, 35 Trip, and several Pen cameras. They are marvelous cameras.

Another great review! I bought one of these new when the 35 SP came out, and loved it. Gave it up (and a Nikkormat Ftn) in a trade for a Nikon SP (!) outfit. Replaced the Nikkormat with a Pentax SL and a180mm f2.8 Sonnar – The Olympus with an Xa .

Thks! I got my LC out, having never used it! (Long story) Love Oly RFs and I HOPE i like this ‘un as much as you do.

The 35S was not Olympus’ first 35mm camera. There were 5 models before it, 35I thru 35V.

The ad right next to the paragraph where you say you couldn’t find a price says the camera sells for less than $80.

Hi Tim, thanks for catching the price right there in the ad! I somehow overlooked it all these years. I have edited the review to include this information. As for the other cameras, you are correct, Olympus did make other 35mm cameras before the 35S, but they were not rangefinders. The article says the 35S was the company’s first 35mm rangefinder camera. Thanks for passing along the corrections though, I always like to fix anything I get wrong.

Hi Mike,

Very good review of this little gem, another simple and efficient Olympus. I had the chance to find one also at 20 euros in France last year and really love the way it behaves like a rangefinder version of the OM1. It was a barn find, dust covered, but after a full CLA, everything was working fine so I was really happy.

I have though one quick question, if you still own it and can check on your own : on mine, there is nothing to prevent advancing the film twice even if you don’t press the shutter in between. Is it the same on yours or do I have to check again under the top if everything is OK ? Not a big problem, I just have to remind not to advance the film right after taking a picture, but I’m still skeptical of this behavior. Thanks in advance for your answer, if any, and long life to your reviews 😉

Frank, thank you for the kind words! I love it when people find older reviews like this for lesser known models and they enjoy reading them!

I do still have the LC in my collection, so I just checked it, and there is definitely an interlock preventing you from continuing to advance the lever without pressing the shutter release. I just tested it and I must press the shutter release before I can advance it again. Sounds like that interlock has failed in yours. If whoever did the CLA on it still warrantees their work, I would check with them, if not, I would just leave it. If everything else is working OK and it is something you can deal with, I wouldn’t risk re-opening the camera and possibly having something else go wrong with it! Just be sure to remember not to waste film with the shutter already cocked! Good luck! (And as a short preview, I will be reviewing this camera’s ‘big brother’ the Olympus 35 SP very soon. I am just putting the finishing touches on it!)

Hi Mike,

Thanks a lot for your quick answer 🙂

Seems I have to put an eye under the top once again, since I did the CLA on my own. With patience and the right tools, it’s not too difficult considering how well designed Olympus cameras are (except for the gluing foams inside the OMs …). I remember I had to remove some old and sticky grease under the counter ring, it looks like I will have to go a bit deeper … if possible. Sometimes, a single piece of dust is sufficient to block a mechanism … I’ll let you know if I find the culprit 🙂

Hi, Frank. Did you find the solution for advance problem? Seems like my 35 LC has the same issue.

I have one. It was my mother’s.

Hi, Mike

Another inspiring review! I was very lucky to get my hands on an Olympus 35 UC a few weeks ago. It has been preserved pretty well with no signs of stains or bumps and fully functioning. I played around with it and find it pretty compact and sophisticated, also producing awesome pictures. I welcome you to my site on lomography to see the results!

https://www.lomography.tw/homes/jouskaa

I am glad you found my article helpful! I had been on a search for a UC model for a while as I really like the way they look, but could never find one at the right price, but since then, I’ve moved on from increasing the size of my Japanese rangefinders. I already have too many!