This is a Panda DF, a 35mm single lens reflex camera made by the Harbin Electric Meter Instrument Factory in the city of Harbin of the People’s Republic of China between the years 1975 and 1979. The Panda is very closely related to the Seagull DF-1 produced by the Shanghai General Camera Factory in Shanghai, China. The Seagull DF-1 is heavily influenced by the original Minolta SR-series SLRs, but despite sharing the same lens mount and a similar design, are not true copies. When demand for Seagull SLRs outpaced the Shanghai’s ability to produce them, an electric meter factory in Harbin was tasked with producing cameras, the first of which was the Panda DF. Like the Seagull DF-1, the Panda DF shares the Minolta SR-mount, and is fully mechanical without any support for an electric meter. Panda cameras made in Harbin are considered to be of lower quality than the Seagulls they are based off, and were replaced by an improved model called the Peafowl DF-1 in 1977.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 58mm f/2 Xiong Mao coated 6-elements in 4-groups (Copy of the Zeiss Biotar)

Lens Mount: Minolta SR-bayonet

Focus: 0.6 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and FP and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, Mirror Lock Up

Weight: 966 grams, 652 grams (body only)

Manual (similar model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/seagull_df-1.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Panda DF is a very interesting and hard to find Chinese SLR made in the 1970s. It was a copy of the Seagull DF which itself was heavily inspired (but not a copy of) the Minolta SR-2. It shares most of the same controls and Minolta lens mount, but adds a mirror lock up lever and a motor drive coupling for a motor drive that was never built. Despite having strong similarities to early Minoltas, the build quality of the Chinese camera is far inferior. Despite this, when found in working condition, the Panda DF is capable of decent results. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for rarity and collectibility | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.0 | ||||||

History

The history of the Chinese camera industry is perhaps the most evasive topic I’ve yet written about on this site. When researching most cameras, there is usually already a wealth of information online, and my goal with these reviews is to piece it all together into a nice and neat article with everything I could find. Even for models where not much is written, there’s usually something about the factory that made it, or the country it came from I can use to supplement what little is known about it.

For Chinese cameras however, discovering more than a couple paragraphs on camera-wiki or camerapedia has been a challenge as there is no central chinesecamera.com website I can do to, or any dedicated Chinese camera collectors I can reach out to further understand its history.

In my brief time writing reviews about Chinese cameras, one of the best resources I’ve found is the book “Cameras of the People’s Republic of China” by Douglas St Denny. In that book’s prologue, a brief intro describes much of the same challenge I’ve encountered learning about the history of the Chinese camera industry. In a country with a long history of revolution, upheaval, and instability has resulted in a lot of information either lost, or not willing to be shared with outsiders.

While a terrific resource, St. Denny’s book is far from complete. It was published in the late 1980s so does not include anything made after that, nor does it benefit from research completed since then. As I began to learn about the Panda DF for this article, I found no reference to it at all in the book. What little I was able to find was pieced together from a handful of Chinese language websites, hastily translated by Google, and a few obscure forum posts I scrounged up on the Wayback Machine.

To even start to understand the Chinese camera industry, you need to first look at the Soviet camera industry. Unlike western countries like Germany, England, and the United States in which commercial companies produce goods to be sold and bought by consumers in the interest of making money, in both the Soviet Union and China, photographic goods were produced by factories operated, or at least strongly influenced by each company’s government. When you hear about a Kiev or Zorki rangefinder, the Arsenal and KMZ factories who produced them did so at the direction of the government. Usually, someone in a position of authority identified a product that needed to be built, and assigned this task to a specific factory. If a factory was unable to meet the demands of the product it was charged in building, another factory would be assigned to pick up the slack. Most of the time, factories that produced a camera almost certainly produced something completely unrelated at one point in its past, changing directions only when told to do so.

In addition to having a system of government similar to the Soviet Union, the early Chinese camera industry saw a great amount of cooperation with Soviet factories. Many early Chinese cameras were copies of Soviet designs, which themselves were copies of German cameras. Chinese Leica II copies were based off Zorkis and early SLRs were copies of the Zenit SLR. Some other designs like the 35mm Smena and Lubitel twin lens box camera were also produced by Chinese companies.

I have found numerous mentions of Soviet and Chinese cooperation in the early days of the Chinese camera industry, but I have observed that these partnerships did not appear to have lasted long, as the Soviet influence seemed to die out by the early 1960s as Chinese cameras started taking more and more influence from Japanese companies. Models based on the Ricoh Auto Shot and Minolta SLRs became common, many with subtle tweaks differentiating them enough to where they cannot even be considered direct copies.

One way in which the Chinese photographic industry continued to mimic that of the Soviet industry is in the organization of camera factories, rather than commercial entities. Manufacturing plants in Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and others began started producing cameras and lenses of nearly ever style, from simple point and shoot to advanced SLR designs.

One of the largest camera producers was Shanghai, where at least five different factories would open, all with generic names like Shanghai Factory Nos. 1, 2, and 3. It is not clear exactly which products were produced at which factories, but models like the Shanghai 58-I and II, Seagull 203, and various Shanghai and Seagull branded TLRs were common both in China, and by the late 1960s even saw some export sales to western countries and other emerging markets.

One of the Shanghai factory’s most ambitious cameras was a 35mm SLR called the Seagull DF. The letters DF are included in the first two digits of the camera’s serial number and is said to come from the Chinese word 单反 or Dānfǎn which translates to English as SLR. Work began on the DF as early as 1964 when an unnamed prototype resembling the final product was first shown.

The as yet unnamed SLR took heavy inspiration from the Minolta SR series, namely the SR-2 from 1958. The camera shared the Minolta’s SR bayonet mount, cloth focal plane shutter, and similar body design. In an unverified and poorly translated Chinese language article, the reason for the close resemblance to the Minolta SLR is thought to have been that engineers at the Shanghai factory found the Minolta’s design to be the easiest to duplicate. Unlike later cameras in the Minolta SR series however, the new Chinese camera did not come with any sort of light meter, nor did it have a provision for one. Also unlike the Minolta SLR, the Shanghai was equipped with a mirror lock-up device, and a provision for a motor drive which was never developed, two things that did not exist on the Minolta cameras.

Shanghai’s new SLR would exist in prototype form until 1966 when the camera went into widespread production and was officially renamed the Seagull DF. The new Seagull camera proved to be a popular seller, not only for its close resemblance to the successful Minolta SLRs, but also its relatively good performance, high quality, and the optics of its 58mm f/2 lens which was a copy of the Carl Zeiss Biotar.

The gallery above shows a Panda DF, the Seagull DF it was based off, and a Minolta SR-3 both were inspired by (I did not have an SR-2 for this photo).

The Seagull DF proved to be a popular camera, selling at one time for as little as 580 Yuan which was within the budget of an advanced amateur looking for a high quality camera and the possibility of importing Japanese lenses. Several variations of the original camera were produced with names like DF-102, DF-103, DF-104, ETM and Reflex DF. The differences between these models is not exactly clear, although it appears the DF-103 had a top indicated 1/500 shutter speed with an unmarked 1/1000 speed like the rest of them and the ETM had an in body TTL exposure meter.

According to an estimate written in Chinese camera historian Zhuang Keming’s book “Chinese Cameras”, as many as 130,000 DFs may have been made. This is a small number compared to those by more established German or Japanese companies, but a huge number for a little known Chinese camera built in a factory with limited resources and without the benefit of a wide export market.

By the early 1970s, sales of the Seagull DF were so high that the factory could not keep up in demand. In 1972, a Chinese manufacturing plant called the Harbin Electric Meter Instrument Factory set a goal to begin producing cameras with a goal of up to 30,000 units per year. It is not clear the exact order in which these events occurred, but it seems as if Harbin Electric Meter Instrument Factory set its goal before having anything to build, or perhaps my conclusion is a misguided result of poor Chinese to English translation.

Whatever the case, with an investment of 3.38 million yuan, Harbin Electric Meter Instrument Factory got to work on their own version of the successful Seagull DF camera made in Shanghai, which they would called the Panda DF. The letters “DF” come from the Seagull DF, in which DF is a loose Chinese translation of ‘SLR’. The Panda was an almost identical copy of the Shanghai produced Seagull DF with the same body, same Minolta SR lens mount, and same list of features, including a motor drive coupling on the base of the camera. No motor drive was ever thought to have been made for either the Seagull or Panda cameras.

In 1973, 10 prototypes were unveiled and submitted for inspection to a quality control institute run by the Chinese government. The very next year, another prototype camera based off the DF was completed which had some type of internal light meter, but the quality of the device was so poor, plans for a metered Panda DF were scrapped, and by 1975, mass production of the Panda DF had begun.

Between 1975 and 1976, slightly more than 5000 Panda cameras were produced, quite a bit less than the ambitious total of 30,000 per year set in 1972, but the Panda DF proved to be a high quality device, winning awards for reliability in 1976 and surpassing every other Chinese cameras in performance and reliability.

In 1977, Harbin Electric Meter Instrument Factory would release a new camera called the Peacock DF-1 which shared many similarities to the Panda, but had a new and simpler design that proved to be even more reliable than the Panda. For a while both Peacock and Panda cameras were produced at the same time, but by 1978 production of the Panda came to a crawl with only 26 units made with production of the camera completely shut down by the start of 1979.

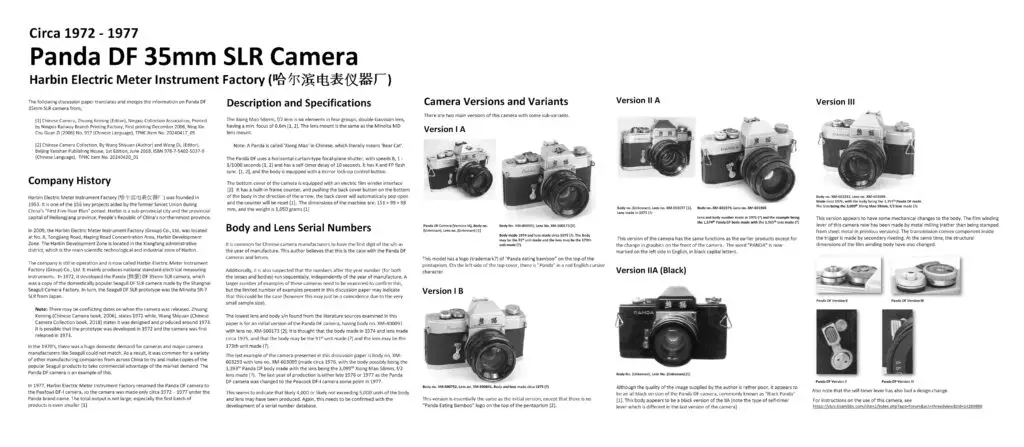

In total, a total of only 6260 Panda DF SLRs were ever built, and although only one official version of the camera was made, up to four variants of it exist. Early Panda DF models have an image of a Panda bear engraved in the top of the pentaprism cover with the Panda logo engraved in red script letters. Shortly after production began, the Panda bear disappeared from the top plate, but the red script Panda logo remained. Shortly after that, the red script logo was replaced with a black block logo seen on the camera in this review. This unofficial third version seems to be the most common as most examples of the camera look this way. A fourth a final version of the camera loses the motor drive coupling on the base of the camera and the design of the rewind knob changes.

Today, it is very difficult to gauge the Chinese camera collector’s market. This is a segment of cameras that is poorly documented and understood. In the western world, we are still uncovering the stories behind models like the Panda DF and for that reason, these are fascinating additions to any collection. That only a little over six thousand were made, make them extremely difficult to find, especially outside of China, but if you are fortunate to get your hands on one, consider yourself very lucky.

My Thoughts

I received the Panda DF at the same time as I received an equally nice Seagull DF. Both cameras were in cosmetically good condition, and both seemed to work. Between the two, the Seagull actually felt a little smoother as the focus ring was a bit stiff on the Panda and the film advance just didn’t feel as smooth, but after doing some preliminary research of the two cameras, the Panda turned out to be the more interesting of the two.

Side by side, both cameras have the same features and every control is in nearly the same location. Differences between the two are mostly cosmetic with the overall shape of the body being similar with the Panda having slightly more squared off edges compared to rounded edges on the Seagull. The two cameras have different self-timer levers and the Panda’s film advance lever has a black plastic tip and an overall different shape. A few other minor cosmetic differences exist such as black trim around the exposure counter on the Seagull, and a red arrow indicating the direction of the door release latch. Finally, the two cameras have the same feel and weight with the only difference seen on a scale where the Panda comes in at 18 grams lighter.

Build quality is much better than I would have predicted a 1970s Chinese copy of a copy of a Japanese camera from the 1950s would be. I’d rank it somewhere below a Minolta SR or SRT but a tick above a Zenit. The body covering is completely in tact with no visible cracks or peeled away edges. The chrome plating was also done well without any rough edges or noticeable signs of oxidation as was common on other cameras with lower quality control.

Up top, the Panda has a fairly typical control layout. Chinese camera makers usually based their cameras after established camera designs by other Japanese, German, or Soviet companies. The control layout of the Panda is very Japanese, which is no surprise as this camera was heavily based off the Minolta SR-series. A rewind knob with fold out handle is on the left, with engraved markings for X and FP sync ports on the side of the camera. The fixed pentaprism has an accessory cold shoe permanently mounted to the top.

To the right of the prism is a combined shutter and film speed selector. Speeds are engraved from 1 to 1/1000 seconds plus Bulb in red and a red X in between 30 and 60 to indicate the roughly 1/40 X-sync speed. Film speeds are indicated from DIN 9 to 36 and are changed by lifting up on the outer ring and rotating. As the Panda has no built in meter or coupling for an external one, this setting serves as a reminder only. The film advance lever has a black plastic tip and requires an approximate 180 degree swing to fully advance the film. The lever is geared so several smaller motions are possible. The shutter release button is in the center of the film advance and is threaded for a cable release. Finally, a round window to the right displays the additive exposure counter which shows the number of exposures made. The exposure counter automatically resets when the film door is opened.

Around back, there is little to see other than the round eyepiece for the viewfinder which has a threaded black ring screwed into it. Remove the black ring and the eyepiece is internally threaded to accept other viewfinder accessories. While I do not believe any were made specifically for the Panda or Seagull, the threading is exactly the same as the Minolta SLRs, so therefore those should all work. To the left and right of the eyepiece are engravings with the camera’s serial number, and the phrase “Made in China” written both in Chinese and English.

The sides of the camera look pretty much the same with the biggest difference being the X and FP flash sync ports on the left side. Metal strap lugs are on the front corner, angled slightly forward to balance the camera when mounted to a heavy lens.

The base of the camera has four things to see. The door hinge side starts with a motor drive coupling which is interesting for two reasons, the first is that none of the Minolta SLRs that both the Seagull and Panda cameras were inspired by ever had such a feature, but also that no motor drive was ever thought to have been made for these cameras. In my research for this camera, every mention suggests none have ever been found. Beyond this coupling, we have a rewind release button, centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, and a sliding switch for the film door release. To unlock the door, simply press in on the release and slide it to the side opposite of where it naturally sits and the door opens.

At first glance, the film compartment looks the same as any other Japanese SLR, but upon closer inspection, this is one area where you can see the lower quality of the Chinese built camera over the Japanese models it was influenced by. While nothing jumps out at being cheaply made, you can see casting marks in the metal and vaguely sharp corners where sharp corners should be, and variations in the black finish. Overall, there is nothing that should cause problems while shooting, but an A/B comparison between the Panda and a Minolta SR-3 and the Japanese camera is clearly better built.

Film transports from left to right onto a single slotted plastic take up spool. When advancing the film, the take up spool spins clockwise which means the film wraps around it opposite of how it is stored in its cassette, which is said to help reduce the natural curl of film. Inside the film door is a black metal pressure plate covered in divots which help reduce friction as it transports. The door channels have no light sealing material, but the hinge has a black velvet seal which on this example was still in good shape and did not need replacement.

Looking down upon the Xiong Mao lens, the control layout is less Zeiss Biotar and more Helios 44. The black painted lens has white engraved numbers for the aperture and focus scales. The aperture ring has clock stops from f/2 to f/16 and moved very easily, with a slight amount of wobble. While no one likes a tight ring, in this case a little bit of dampening would have improved the feel. Towards the front of the lens, the all metal focus ring turns with a bit of tightness from 0.6 meters to infinity. A full movement requires about a 270 degree turn. There is no focus scale in feet. The Xiong Mao lens has an automatic diaphragm, but unlike other automatic Minolta lenses, a depth of field preview lever sticks out of the side of the lens. With the lens mounted to the camera, this triangular shaped piece of metal is at about the 8 o’clock position.

Up front, the Panda resembles a typical SLR. The Minolta SR bayonet has a lens release button in the same location as other Minolta cameras, near the 1 o’clock position of the lens mount. Push this button toward the lens while rotating it counterclockwise to remove it, and line up the red index dots and twist clockwise to remount the lens.

Lens Compatibility: I tried a couple combinations of other Minolta Rokkor lenses on the Panda camera and the Xiong Mao lens on other Minolta cameras and found that compatibility was not 100%. The Xiong Mao lens mounted without issue to both a Minolta SR-3 and a Minolta X-700 and worked as expected, however I had issues with genuine Rokkor lenses on the Panda. An Auto Rokkor-PF 55mm f/1.8 lens mounted correctly, but was very tight and required a bit of force to get it on suggesting the tolerances of the Chinese camera were not up to Minolta’s. With the lens mounted, the automatic diaphragm worked correctly and I had no other issues. I also tried an MC Rokkor-X PG 50mm f/1.4 lens and it would not mount to the Panda at all. At first, I assumed the additional linkages added to the MC and later MD lenses would not allow the lens to mount to such an early camera, but when I tried the MC lens on the older SR-3, it mounted without issue. To confirm my suspicion of new lens incompatibility, I also tried an MD Macro Rokkor-X 50mm f/3.5 lens and it too, would not mount to the Panda. That later MC and MD mount lenses didn’t work with the Chinese Panda wasn’t likely an issue for owners of this camera as they came from different eras and likely were not easily available in China at the time.

Next to the lens mount is a mechanical self-timer lever which when fully wound, gives an approximate 8-10 second delay before firing the shutter. To use the self-timer, a button behind the self timer lever must be pressed in the direction of the lens mount with the shutter cocked. Pressing the normal shutter release with the self-timer activate doesn’t activate it. Finally, on the left side of the mirror box is the mirror-up lever. This lever works as expected, but its inclusion on the camera is curious as no Chinese lenses were ever made that interfered with the mirror. You could use it to reduce shake caused by mirror slap at slow speeds, but that’s the only reason I could see to use one.

The Panda’s viewfinder is as basic as they come. This probably shouldn’t come as a surprise for a copy of a camera that was based on a camera from the late 1950s, but to have purchased a new camera in the mid 1970s with a simple ground glass focus screen with no exposure information or focus aides is a bit shocking. Although there are merits to an entirely ground glass focus screen, other cons are that the viewfinder is rather dark and shows heavy vignetting even with the lens wide open. Corners are darker than the middle which isn’t a huge problem outdoors in good lighting, but as soon as you step into anything even remotely dark, seeing a focused image becomes quite difficult. Strangely when taking the through the viewfinder image to the right using my smartphone, the image appeared brighter than it does with the naked eye.

When comparing the Panda DF to that of other Japanese or German cameras from the 1970s, or even the original Minolta SR-series from the late 1950s, the Chinese camera is clearly inferior. Forgiving the camera’s stiffness can be forgiven due to age, but I suspect that even when new, this was a lower quality camera with rougher edges and poorer performance.

I don’t think it is entirely fair to do an apples to apples comparison however, as what was available to Chinese photographers in the mid 1970s was not what we could get in the United States or other western countries. When you look at what communist countries had available to them, the Panda starts to look more favorable. Despite its crude build quality, the original Minolta design is still in there. The camera works like a Japanese camera, and I suspect with good sample variation, in good condition, these were capable cameras. Since this is the only Panda DF I’ve ever handled, the only way to know what this camera is like to shoot, is to load in some film and actually shoot it! Keep reading…

My Results

Everything during my preliminary test of the Panda DF suggested it was in working order, but the camera was in rough condition and everything was tight. While it seemed like I should be able to get through a roll, I wasn’t going to bet my life on a low production Chinese camera from the 1970s, so I took it out with some expired film and figured if I got a couple good images, I’d be happy. For my film choice, I went with a film I picked up several years ago but haven’t used much, which is Eastman 2484, a high speed panchromatic black and white film from the 1980s, which I believe was originally used to photograph CRTs. I’ve shot this film before and found that it exposes well at ASA 100, but even at that still has very pronounced grain. I figured the grit of the communist Chinese camera would suit a gritty film, so I loaded up a bulk roll and took the camera out shooting.

Amazingly, despite my initial concerns of imminent doom, the Panda DF survived its entire first roll of film in who knows how many decades. Other than general stiffness, which I am starting to think is just how this camera always was, it proved to be an enjoyable experience.

The images I got from the 58mm f/2 Xiong Mao lens were decent, but not spectacular. The shutter worked at all speeds, and seemed accurate enough while shooting Sunny 16 using ASA 100 speed film. It is easy to assume this 58mm f/2 lens is probably a copy of the Helios-44 which itself is a copy of the Carl Zeiss Biotar, but a Zeiss lens this is not. Whatever differences occurred between the original Jena produced lenses and this lens resulted in images that were extremely soft wide open with prominent vignetting and softness near the corners. While I stand by my decision to use the expired Kodak 2484 film, the extreme grain made it difficult to see how sharp this lens is, but I predict it would have been “good enough” at apertures of f/8 and smaller.

Using the camera was a mixed experience. On one hand, this camera is still very similar to a late 1950s Minolta, which wasn’t a bad camera. Although I would describe the build quality as less than that of the original Japanese camera, this Chinese iteration does nothing to significantly worsen the experience. In fact, if having a mirror lock up feature is useful, you could even say that this camera makes improvements to the original Minolta design. For me, the best thing I can say about the Panda is how familiar it is. No liberties were taken with this camera’s design or ergonomics, and I see that as a win.

I’ll likely never know how close (or different) this Xiong Mao lens is to the 58mm f/2 Biotar it is based on, but it is clear this is a lesser lens. The viewfinder is darker than pretty much any SLR from the 1970s, and the camera is stiff overall. But it works. I had no problems shooting my test roll, the camera has no strange locations for its controls, and the camera did everything it was supposed to.

I’ve read that later Chinese cameras continued to improve beyond these early Panda and Seagull SLRs and that can only be a testament to the people who put together this Panda, so as an evolutionary model, I guess you could call it a success. I quite liked my time with the Panda and am happy to have it in my collection. As a camera however, there are MANY much better options out there. I think that over time, the tightness would become bothersome, and I still believe that this camera is much closer to failure than anyone should feel comfortable with if they intended to use it regularly. If you have a thing for Chinese cameras, or just like something that’s different, you could do a lot worse however.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://www.subclub.org/minchin/panda.htm

https://www.flickr.com/photos/80936052@N00/53730939611/in/photolist-2pS27ox

https://ishare.ifeng.com/c/s/7sDozMF9nGq (in Chinese)

https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1730633008028941970&wfr=spider&for=pc (in Chinese)

Minolta did make early cameras with provision for auto winder, both the SR2 and SR1 early models had a provision. Exactly as for the Chinese models, no winder was ever released.

I have a Panda camera, but it works correctly so I have never taken any covers off. However, I also have a Peafowl DF-1 on which the slow speeds did not work when I received it. I managed to repair the problem, and in the process noticed that the Seagull and Panda/Peafowl cameras use the same shutter mechanism. The shutter and mirror box are removable as a separate assembly, just the same as a Copal square or Praktica vertical shutter equipped camera. The shutter assembly for the Chinese cameras is good quality, and I think the shutter/mirrorbox assembly was likely made in one factory, and assembled elsewhere for these models. I also have a working Pearl River SLR. I haven’t taken the covers off that one either, but it would not surprise me to find the same shutter/mirrorbox assembly in that camera as well.

In early 1980s of China , the Seagull DF series cost twice much as the Seagull TLRs, only the technicians and policemen could afford. The technicians in Harbin Electric Meter Factory tried many times to add an affordable TTL system to the SLR but failed at last.