This is a Perfex Forty-Four 35mm rangefinder camera made by the Candid Camera Corporation in Chicago in 1939. The Forty-Four was the first in a series made by the Candid company until the early 1950s at which point the company out of business. Featuring an interchangeable screw mount with a variety of lenses, a coupled rangefinder, synchronized flash hot shoe, and a cloth focal plane shutter with a top speed of 1/1250, the Perfex was an ambitious American camera that for a short while, kept American cameras near the cutting edge of new technology.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/3.5 Graf Perfex Anastigmat uncoated 3-elements

Lens Mount: 38mm Screw Mount

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Viewfinder and Rangefinder Split Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1250 seconds

Exposure Meter: Extinction Meter

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Hot Shoe with Perfex Flashbulb Sync

Weight: 696 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/perfex_fourty-four.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Perfex Forty-Four was the second and most feature packed model in Candid Camera Corp’s Perfex lineup. It had a competitive feature set including a top 1/1250 shutter speed, interchangeable lenses, an exposure meter, split window coupled rangefinder, and came with a variety of quality lenses. The camera has surprisingly modern ergonomics and is comfortable and fun to shoot. I got some really nice photos from the camera despite it’s age and uncoated optics. Many American cameras were made in the first half of the 20th century with ambitious features, but the Perfex Forty-Four is likely the best I’ve ever used. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.2 | ||||||

History

The Perfex Forty-Four was made by a company called the Candid Camera Corporation, located in Chicago, IL. In the entire history of American photographic companies, the Chicagoland area wasn’t exactly known as a dominant force in the industry. In fact, Chicago’s greatest claim to fame was an inexplicable number of cheap Bakelite cameras made under a dizzying number of companies and cameras like the Utility Manufacturing Corp with the Falcon camera, the Pickwik, Spartus Corp, Herold Manufacturing Corp, General Products Corp, ACRO Scientific Products Co., The Spencer Company, Metropolitan Industries with their Clix-O-Flex, Monarck Manufacturing Corp, and many, many others. Strangely, many of these companies all shared a similar address of 715 W. Lake St in Chicago. Camera-Wiki.org has a huge list of many of the companies and variations on these cheap cameras if you’d like to know more.

The Perfex Forty-Four was made by a company called the Candid Camera Corporation, located in Chicago, IL. In the entire history of American photographic companies, the Chicagoland area wasn’t exactly known as a dominant force in the industry. In fact, Chicago’s greatest claim to fame was an inexplicable number of cheap Bakelite cameras made under a dizzying number of companies and cameras like the Utility Manufacturing Corp with the Falcon camera, the Pickwik, Spartus Corp, Herold Manufacturing Corp, General Products Corp, ACRO Scientific Products Co., The Spencer Company, Metropolitan Industries with their Clix-O-Flex, Monarck Manufacturing Corp, and many, many others. Strangely, many of these companies all shared a similar address of 715 W. Lake St in Chicago. Camera-Wiki.org has a huge list of many of the companies and variations on these cheap cameras if you’d like to know more.

It would seem that Chicago was only known for cheap Bakelite cameras, but there was one exception, the Candid Camera Corporation. Candid was formed in May, 1938 by Carl and Joseph Price, and Benjamin Edelman. Like Argus, these men reportedly had experience in the radio industry, possibly working for another midwestern company, before turning their attention to making cameras. Their original address was on the 4th floor of a six-story building at 844 West Adams Street in downtown Chicago.

The company’s first camera was released in October 1938 and was called the Perfex Speed Candid. Built around a Bakelite body that strongly resembled the Argus A-series, the Perfex was a pretty sophisticated camera, featuring the first ever American made cloth focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/25 to 1/500, an uncoupled rangefinder, extinction meter, and an interchangeable helical focus mount. The camera is most often seen with a 2 inch (~50mm) f/3.5 Graf-Perfex anastigmat lens, but there were 2 inch f/2.8, 4 inch f/4.5, and 6 inch f/4.5 auxiliary lenses available as well. For closeup work, an interchangeable ground glass focusing back was made available along with a set of extension tubes making the Speed Candid a rather flexible “system” camera.

Although using a lot of Bakelite in the construction of it’s body, the entire front of the camera along with the shutter box was made entirely of die-cast metal. The camera weighed over 2 lbs and had terrible ergonomics making it very clumsy and difficult to use. Despite the off-putting looks and difficult controls, the Speed Candid sold reasonably well. At least good enough to warrant an upgraded successor.

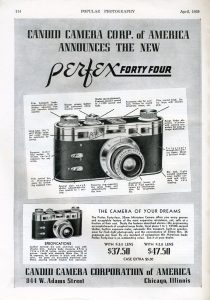

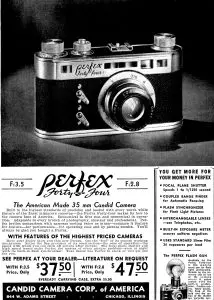

In 1939, an entirely new Perfex called the Forty-Four was released with an all new die-cast body, upgraded shutter, 3½” wide base coupled rangefinder, and flash hot shoe on top of the camera. The Forty-Four was a much better looking camera and it retained most of the Speed Candid’s best features such as the interchangeable lens mount, focal plane shutter, and extinction meter. The upgraded shutter boasted an ambitious top speed of 1/1250 which tied the Zeiss-Ikon Contax for the fastest available cloth focal plane shutter in the world. It seems that Candid took a few cues from both the Zeiss Contax (top 1/1250 shutter speed and long base rangefinder) and combined it with some features from the Leica III (horizontally traveling cloth focal plane shutter and screw lens mount). Nippon Kogaku would take a similar approach a decade later with their first Nikon rangefinder, by borrowing what they liked from the two cameras and making their own.

Selling for $47.50 with the Graf f/2.8 lens and $37.50 with the f/3.5, the camera was quite a bargain compared to European models that were selling for more than 5 times as much. When adjusted for inflation, these prices are like $675 and $850 today.

Despite a much improved appearance and competitive feature set, Perfex cameras were plagued with reliability issues from the very beginning. The Candid Camera Corporation was still a very small and new company and they didn’t have the expertise to machine and build most of the camera’s parts, so nearly every part was outsourced to other companies which caused large variations in quality control. The new synchronized flash hot shoe was a bit ahead of it’s time and required long-duration flashbulbs which were not available when the camera was built, causing problems getting properly exposed images using the flash. Other issues with the slow speeds, film transport, and a tendency for the lens to unscrew when focusing the camera also hindered it’s success.

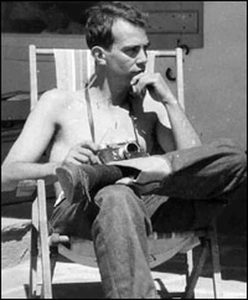

Still, the Perfex Forty-Four sold mildly well, and for a short while, was seen as the most advanced American made camera, beating out competing models by Argus, Clarus, and Kodak. The Forty-Four spawned a whole series of similar looking Perfexes starting with the nearly identical Fifty-Five and simplified Thirty-Three, both in 1940. A fun fact about Perfex cameras is that the first ever color photograph of a nuclear explosion was captured by photographer Jack Aeby using a Perfex camera. Wikipedia suggests this was a Thirty-Three, but in the image to the left of Aeby holding his camera, the presence of round dials on the front of the camera suggest it was a Fifty-Five.

World War II halted production of Perfex cameras, but afterwards, the Fifty-Five was the only pre-war model to resume production. The Perfex was quickly outsold by it’s competition and in an effort to lower the price, the camera went through a significant simplification, replacing the focal plane shutter with a Wollensak Rapax leaf shutter and removing some of the camera’s features. Slow speeds and the extinction meter were gone, and body plates were no longer die cast, but rather stamped metal plates.

Soon, what was once an ambitious and competitively featured American rangefinder, turned into a cheap knockoff of itself retaining little of the charm or quality of the original. Later models like the Perfex One-o-Two from 1948 were the last cameras made by the original company.

One year prior to the collapse of the Candid Camera Corporation, a revised model called the Cee-ay-35 was created with a more sophisticated body design, but it was too little too late. The design of the Cee-ay 35 was sold to fellow American company, Ciro, who rebadged the camera as the Ciro 35 and continued to make it for a few more years as an inexpensive American rangefinder.

Today, none of the Perfex models are sought after outside of small niche collectors who enjoy quirky old American cameras. The pre-war models are slightly more desirable mainly because of their rarity and the fact that at one very brief moment in time, these were actually seen as serious cameras. The Forty-Four is pretty rare as it was only made for about a year and a half, so the Fifty-Five is a better option as it was made in much greater numbers and has a nearly identical feature set. Whether you get a Forty-Four or Fifty-Five, they both have the best combination of the Candid Camera Corporation’s early ambition in an attractive body and with specs that still are capable of good photographs.

My Thoughts

This Perfex Forty-Four was the second Perfex to come my way, the first being a completely inoperable One-o-Two that I previously reviewed in my ‘Cameras of the Dead’ series. The One-o-Two was a less than glamorous introduction to the Perfex lineup for me. It was a pretty basic camera with only a Wollensak leaf shutter and lens grafted onto a hollow die cast metal body with a stamped metal top plate. The camera was big, heavy, clunky, and didn’t work. It didn’t take me long after handling it to imagine that had the camera been working, I likely wouldn’t have enjoyed using it. I made no attempt to repair the camera, wrote a little article about it, and sold it off on eBay for a couple of bucks.

In November 2016, while working on a review for the excellent American made Clarus MS-35, I started talking to fellow collector and master camera repairman, Richard Oleson and the topic transitioned to other American rangefinders and he asked if I had ever used a Perfex. Telling him my sole experience with the One-o-Two, he told me I should check out a Forty-Four, and just my luck, he had a couple of them. After arranging a fair trade, I eventually wound up with this Forty-Four from Richard’s personal collection. He assured me that the camera was in good working order except for the slow speeds, but that everything else should be fine.

True to his word, when the camera arrived, everything tested out OK and seemed ready to go. From the moment I took the Forty-Four out of the package, I could immediately see there was a world of difference between this early model and the later leaf shutter ones. For anyone in a similar situation as I where you’ve only seen the later models, you should know that they weren’t always that way.

Other than sharing the same vague shape, about the only other similarity between this camera and the One-o-Two is the large size and weight. Weighing in at one and a half pounds, the Forty-Four has a bit of heft. Lacking any provision to attach a strap, the only way to support this camera is either a tripod socket strap, or by using the original case that it would have come with.

The top of the camera resembles other American rangefinders like the Clarus MS-35 and has symmetrical rewind and wind knobs at opposite ends with a flash hot shoe in the middle, along with a shutter speed selector collar around the shutter release. Unlike the Clarus however, the Perfex offers slow speeds from 1 second to 1/10 in red which requires a lever on the front of the camera to be moved to the slow speed position. All over speeds plus Bulb are in black. A word of caution, there is another popular website with an otherwise good review of the Perfex series which incorrectly states that the film advance is done by rotating the shutter speed dial. Although this technically works, it is not correct, and the camera’s manual specifically states not to do this.

On the front of the camera below the Perfex logo are two levers. The top lever has the letters “R” and “T” on them and is used to control the transport of the film. Normal operation of the camera requires this lever be set to “T” which I assume means “Transport”, but when reaching the end of a roll “R” allows it to be rewound.

The second lever is the selector for slow and fast speeds, with “S” using the red shutter speed numbers 1 – 10 on the top plate, and “F” for all of the black numbers. On my example all of the slow speeds caused the second shutter curtain not to close, so I couldn’t use them. On the later Fifty-Five, this lever was replaced with a wind up knob, somewhat similar to how the slow speeds on the Ihagee Exakta work. In Rick Oleson’s review of this camera, he suggests that the slow speeds on the Fifty-Five are more likely to work as they have an improved design.

The bottom of the camera continues Candid’s preference for chrome levers with two levers on each end that are releases for the film compartment. Each lever has the words “Open” and “Close” and when rotated in the corresponding direction, releases a lock to remove the entire back and bottom of the camera for film loading. In the center is a standard threaded tripod socket.

Upon removing the rear of the camera, you are presented with a surprisingly modern film compartment, especially considering this camera was built in 1939, only 5 years after the 35mm film format was invented and far before there was any semblance of consistency in 35mm camera design. A new roll of film goes on the left, stretching the leader across the film plane, over a pair of sprockets and onto a removable take up spool.

The Perfex Forty-Four is a unit focusing camera, which means the entire lens is rotated when adjusting the focus. This causes a few problems when using the camera. In the image to the right, the knurled ring closest to the body is the body-mounted focus ring that is used to focus from 3 feet to infinity. Since this ring is so close to the body, it can be difficult to locate this ring with the camera to your eye, so you can optionally grip the lens at any black painted point and rotate it, but since it is also a screw mount lens, this can have the side effect of unscrewing the lens from the mount.

This also has the side effect of rotating the aperture ring which is the one farthest from the body. The f/stop scale rotates with the lens, so depending on what distance the camera is focused at, the scale can be anywhere on the lens. With the lens set to minimum focus, the scale points up, but as you can see in the image above of the bottom of the camera, it is pointing down. In the image to the left, you can see the aperture scale facing the side when the lens is set to infinity. As obnoxious as this sounds, this was actually quite common in early screw mount cameras and only an issue when changing f/stops.

Speaking of screw mounts, the Perfex Forty-Four is an interchangeable lens camera. Using a proprietary 38mm size, you can only use lenses designed specifically for Perfex cameras. Simply rotate the lens counterclockwise (lefty-loosey) to remove the lens and swap it out with another. The original owner’s manual for the Forty-Four suggests that only the two 2 inch (~50mm) lenses and a 6 inch (~150mm) f/4.5 telephoto lens were available, but according to “Glass, Brass, and Chrome: The American 35mm Camera” by Kalton Lahue and Joseph Bailey, there was also a 4 inch (~100mm) f/4.5 lens available for the earlier Perfex Speed Candid, although I am unsure if it was compatible with the Forty-Four.

Moving around to the back of the camera, we see the dual viewfinder/rangefinder windows. As was common with prewar 35mm rangefinders, the rangefinder was of the split image type and magnified the image somewhat, allowing you to see a precise closeup of the center of your composed image. Like the Zeiss Contax, the Perfex has a very wide 3½” base to the rangefinder which improves accuracy.

To properly compose the entire image however, you needed to move your eye to the separate telescopic viewfinder. Compared to the large and bright viewfinders from the second half of the 20th century, this system feels antiquated, but compared to other cameras like the Argus C-series and Leica II and III that used a similar system, the viewfinder in the Perfex was a bit larger and easier to use for people with prescription glasses. I had no problem seeing the entire composed image through the viewfinder without having to press my face against the camera.

Next to the viewfinder window is a long slit for the extinction meter. Extinction meters were an early form of exposure metering that involved a strip of semi transparent film that would start out very transparent and get more and more opaque as you went left to right. On the strip are several letters (other companies used numbers) that would correspond to a primitive “light value” on the round calculator in the middle of the back of the camera.

In the image to the right, you can see the seemingly random sequence of letters “KDIALGEJBFVCPHOT” and the idea was that the darkest letter that you could still make out with the camera 12 inches from your eye, would correspond to the correct exposure value of the scene you were shooting. In lower light, you’d only be able to see the first few letters on the left, but in bright light you’d be able to see the letters farther to the right.

Once you had an exposure letter, you’d use the rotating disc on the back of the camera and first rotate the outer disc to match the letter to an f/stop value on the top half of the calculator. You’d then look at the bottom half and match up whatever film speed you have in the camera (or whatever is closest) to a matching shutter speed (or whatever is closest). For example, lets say lighting conditions dictate exposure value “V” and you’re using Kodak Portra 160 film (the calculator has a setting for 175 which is close enough to 160). Matching the letter “V” to f/5.6 suggests a shutter speed of about 1/200. If you wanted to use a smaller aperture for more depth of field, turning the “V” to f/16 suggests a shutter speed of about 1/25.

The system was primitive and subject to interpretation depending on the user’s eyesight, but it did work and offered a creative solution to light metering in an era when electronic light meters were still in their early days, and also very expensive. I also found it interesting that the calculator on the back of the camera has film speeds from 0.75 all the way to 1000, and f/stops from f/1.5 to f/64. Was Candid ambitious and thought that maybe one day they’d make an f/1.5 lens to compete with Zeiss? Who knows!

Overall, the Perfex Forty-Four had a very competitive feature set, and its controls and ergonomics were quite good. All of the controls are exactly where you’d expect to find them on a modern camera, and for someone used to shooting classic mechanical cameras, there’s nothing here to trip you up the first time you pick it up. The only thing to find out, is how the images look.

My Results

I loaded a roll of fresh Fuji 200 into the Perfex for it’s first roll in the spring of 2018 and took it with me on a trip to Lansing, Michigan. As much as I appreciated the experience of playing with the camera’s extinction meter, it’s a bit impractical to use for real-world calculation of shutter speeds, so for this first roll, I shot everything using the Sunny 16 rule.

I am always the most excited to see results from a new vintage camera when it’s something old or quirky. The Perfex Forty-Four was both of those things so I was super excited to pull the film from the Paterson tank after developing it using the Film Photography Project’s C41 developing kit.

The first thing you’ll see in a lot of these images are obvious light leaks which I guess I should have predicted due to the way in which the film door seals against the body. In hindsight, it seemed loose to me and probably would have benefited from some additional light seals, so I’ll have to keep that in mind for my next roll.

But beyond that, the images were spectacular. The colors are a bit washed out, likely due to the uncoated Graf lens, but they are sharp and well defined across the entire frame. In the image of the Michigan capital building in the gallery above, there is hardly any sharpness fall off near the edge of the frame. You can still clearly read the “Chandler Plaza” sign near the left edge of the photograph. There’s also no obvious vignetting either which suggests that whoever worked at “General Scientific Corp” making these lenses knew what they were doing. Everything I have read suggests these are 3-element lenses, but with the performance of this lens, I would not be surprised if this wasn’t some sort of 4-element lens like the Leitz Elmar f/3.5.

I really enjoyed shooting the first roll of film through the Perfex Forty-Four. What I love about American rangefinders from the mid 20th century is that they were often quite different than their German counterparts. The early parts of both the Japanese and Soviet camera industries relied heavily on German copies. It is clear there was an attempt by companies such as Clarus and Candid to include features that compared to German cameras, but no matter how much you blur your eyes when looking at one, you’ll never mistake an American rangefinder for something made by Leitz or Zeiss. I think American cameras get a bad rap from collectors which I don’t think is justified. Cameras like the Argus C44, Kodak Signet 35, and Universal Mercury II are all very capable and distinct cameras that make excellent photographs and are fun to use.

These cameras have character, they have quirks, and like any old camera, they sometimes need help to get working again, but when they do work, they are often quality shooters. If you ever have a chance to pick up an early Perfex like this in working condition, Rick Oleson and I both encourage you to go for it. Not only is it a pretty camera, but it’s pretty good too!

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Perfex

http://rick_oleson.tripod.com/index-8.html

https://www.cameraquest.com/perfex.htm

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/a-perfex-camera-the-perfex-forty-four-of-1939.432869/

Thank You, it’s an excellent Reviews of a rare camera.

August 17,2019. Just picked up a Forty Four at a rummage shop along with a Weston Model 853 light meter, all for $20. The camera needs some dusting off, and it seems there is still a roll of film in it. Googled the model and this is the first site that came up – very informative, and all the more interesting to me since my last name is also Eckman. I’m looking forward to cleaning it up and running some film through it.

$20 is a great price to pay for a fine camera! Most of them just need a good cleaning as these are pretty simple cameras that should usually stay working! If you ever shoot any images in it, be sure to let me know! Also, great last name! Be sure to subscribe to my site and see my future posts!

I’m a proud owner of a Forty Four and I enjoyed a lot of shots with. A question: has anybody seen, even in a photograph, the almost “mythical” 6″ tele lens? I mean, really nobody bought it in the past? so, is a interchangeable lens camera at all…

Massimo

General Scientific Corporation apparently still exists as the parent company of SurgiTel (Ann Arbor, MI) which makes medical loupes and related items. According to their website, GSC has been making optical products since 1932.