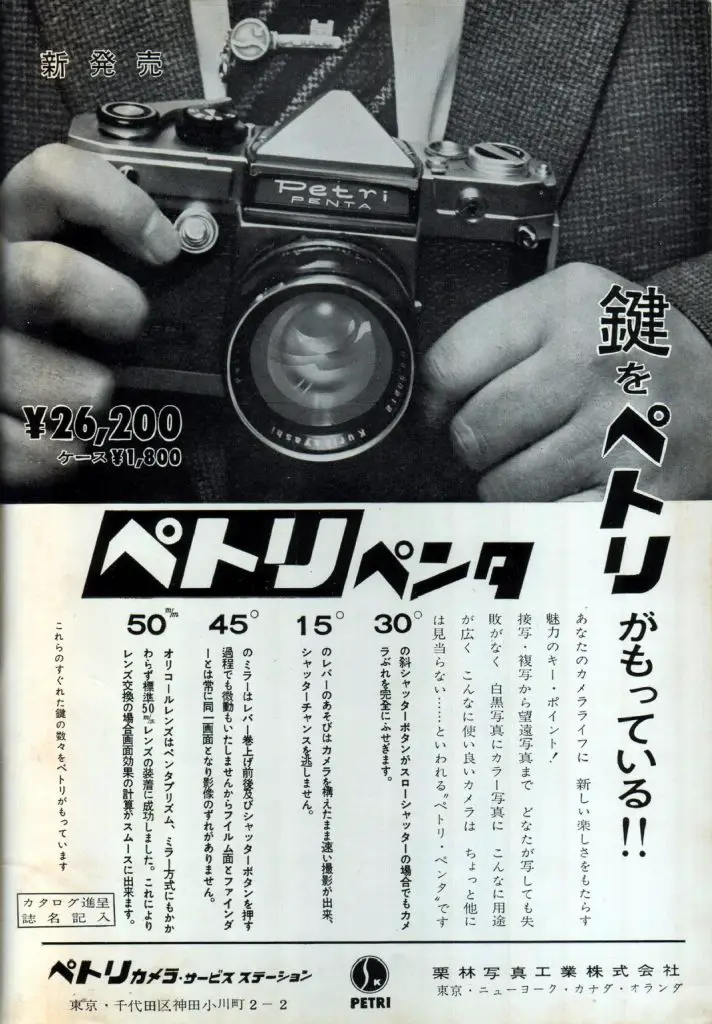

This is a Petri Penta, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made in Japan by Kuribayashi Shashin Kōgyō K.K. starting in September 1959. The Penta was Kuribayashi’s first 35mm SLR as they had been producing a line of scale focus and rangefinder cameras for about ten years prior. The Penta was slightly smaller than most SLRs of it’s era and used the common M42 “Praktica” screw mount meaning that a huge number of German and Japanese lenses out there were compatible with it. Strangely, a year after it’s release, Kuribayashi would abandon the M42 screw mount and switch to using a unique Petri breech-lock bayonet lens mount. Petri made an M42 adapter to allow continued use of it’s screw mount lenses. This original Petri SLR is uncommon today and with it’s Orikkor 50mm f/2 lens, is quite valuable.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2 Kuribayashi Petri Orikkor coated 7-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: M42 Screw Mount

Focus: 1.75 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: FP and X Flash Sync Port

Weight: 803 grams (w/ lens), 607 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/rl/01653/01653.pdf

Manual (in Japanese): https://onedrive.live.com/download.aspx/pub/PetriPenta.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Petri Penta was Kuribayashi’s first attempt at an SLR, and although it was an economy model, it was still well built with some competitive features and came standard with an excellent lens. These cameras aren’t known for their reliability and can be hard to find today in good working condition, but as an attractive and compact alternative to the larger, more mundane Japanese SLRs of the era, it’s worth seeking out if you have a chance. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.8 | ||||||

History

Kuribayashi was founded in Tokyo, Japan in 1907 by Kuribayashi Yōji and made a variety of photographic equipment like tripods and dark boxes. The company would eventually make it’s first camera in the 1920s known as the Speed Graphic. It was a large format plate camera that could be custom ordered with a variety of lenses and shutters.

In the 1930s, Kuribayashi made many folding roll film cameras such as the Semi First and First Six. These cameras were very similar to designs by German companies such as Balda and Welta and often were sold without any identifying marks. Many of Kuribayashi’s early products were sold by third parties under a variety of names. One of the more common names used was First Camera Works which was sold by a third party called Minagawa Shōten. For this reason, it can be incredibly difficult to identify an early Kuribayashi made product.

During World War II, at least one of Kuribayashi’s offices in Tokyo was destroyed. There isn’t much information about what the company was doing around this time, but like most other Japanese optical companies, they were likely ordered by the Occupation Forces to begin producing items for commercial sale in an effort to rebuild Japan’s economy.

It wouldn’t be until 1949 when Kuribayashi would regroup and change names to K.K. Kuribayashi Shashin Kikai Seisakusho and move to Chiyodo, Toyko. At this time, the company also ended it’s ties with Minagawa Shōten and would cease selling products under the First Camera Works name. The company would release two new lines of cameras, one called the Kuribayashi Karoron which would be a lower end line of folding cameras loosely based on the Zeiss-Ikon Ikonta, and a TLR called the Petriflex.

Petri’s first 35mm rangefinder was released in 1954, simply called the Petri 35. It was a fairly modest model featuring a 45mm f/2.8 Orikkor lens and a simple shutter with a top speed of 1/200. The camera didn’t stay simple for long however, as Petri continually evolved the model, improving the design with more features, faster lenses, and better shutters.

A large number of Petri rangefinders, many with nearly identical features to previous models would be released over the course of the next decade. As was the case with pretty much every other Japanese camera maker, the rise in popularity of Single Lens Reflex cameras caused the company to invest in it’s first 35mm SLR.

During Kuribayashi’s development of their first SLR, they were likely already aware that they either couldn’t, or it wouldn’t be worth it to compete in the professional camera segment, so their priority was in making an economical camera that emphasized it’s value over innovative features. When it would finally be released, the user manual for the Petri Penta featured in red letters the motto of “High Quality Cameras at Lowest Possible Prices”.

Whether it was intentional or not, Kuribayashi’s camera seemed to borrow a few pieces of the design from the Asahi Pentax including it’s compact size, M42 screw lens mount, and fixed pentaprism viewfinder.

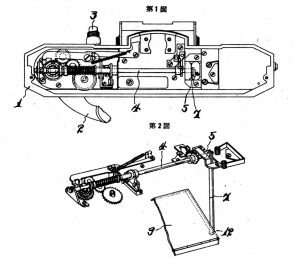

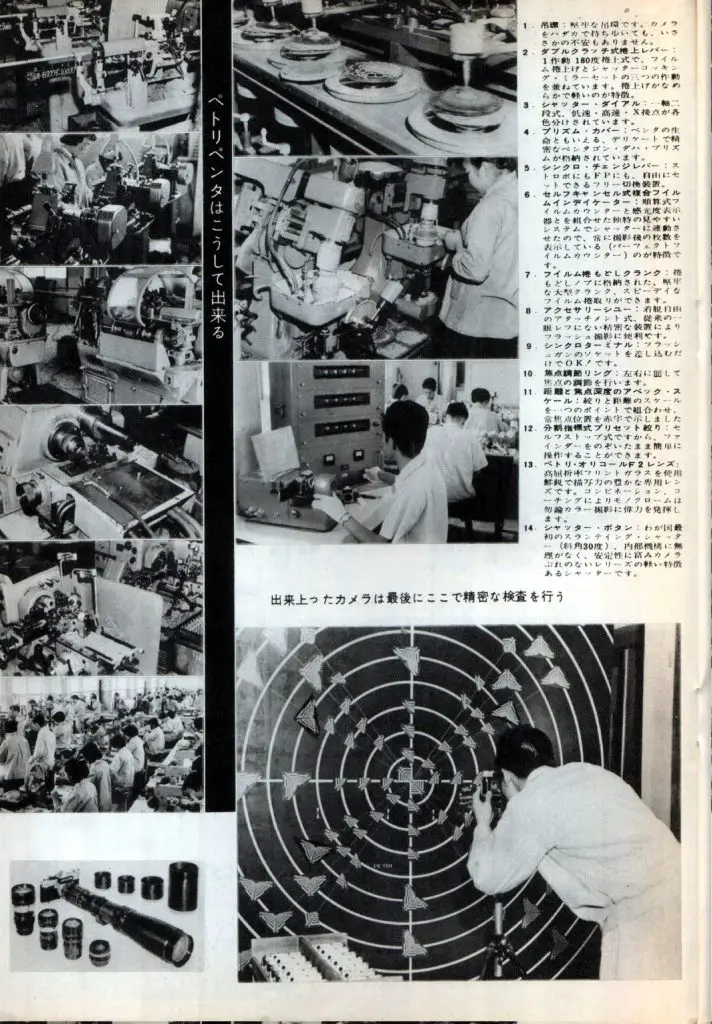

One area in which they didn’t borrow from anyone however, is in how the shutter works. Without getting too technical, nearly every camera ever made with a focal plane shutter uses some system of vertical gears and springs that tension a drum in which both the first and second shutter curtains are rolled onto. When the film advance knob or lever is advanced, a system of gears tensions a spring that pulls back the first curtain and replaces it with the second curtain. When the shutter is fired, the tension on the spring is released and the second curtain snaps back onto the other drum, with a gap between it and the first curtain set by the shutter speed dial, which determines the exposure.

Although Kuribayashi used a similar arrangement of two drums with cloth curtains, the method in which the shutter is tensioned used a long steel shaft, horizontally located at the very bottom of the camera. A torsion spring, similar to ones found above garage doors rotates the shaft and provides the tension. When the shutter is fired, the tension on the torsion spring is released, spinning the shaft, which is connected to the drums, making them move.

In the video below which I previously made on a Petri Flex V, you can see the coils of the spring being twisted as I wind the lever. Upon pressing the shutter release, the spring and shaft quickly rotate back into their original positions.

Kuribayashi would use this shaft driven method for their shutters on everything from the original Penta until the Petri FT II from 1971 which changed to a more traditional design midway through that model’s life.

In my research for this article, I found an interesting note on this Japanese language Petri wiki that suggests that the earliest Petri Penta cameras did not use the shaft driven shutter design, instead using a more traditional one. It seems unlikely that Kuribayashi would have had sufficient time to develop one shutter design, and then quickly abandon it and start over with something else, so my best guess is both methods were developed in parallel and the shaft drive system won out.

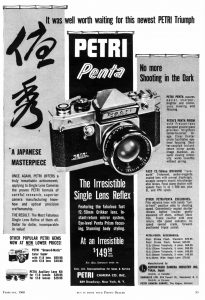

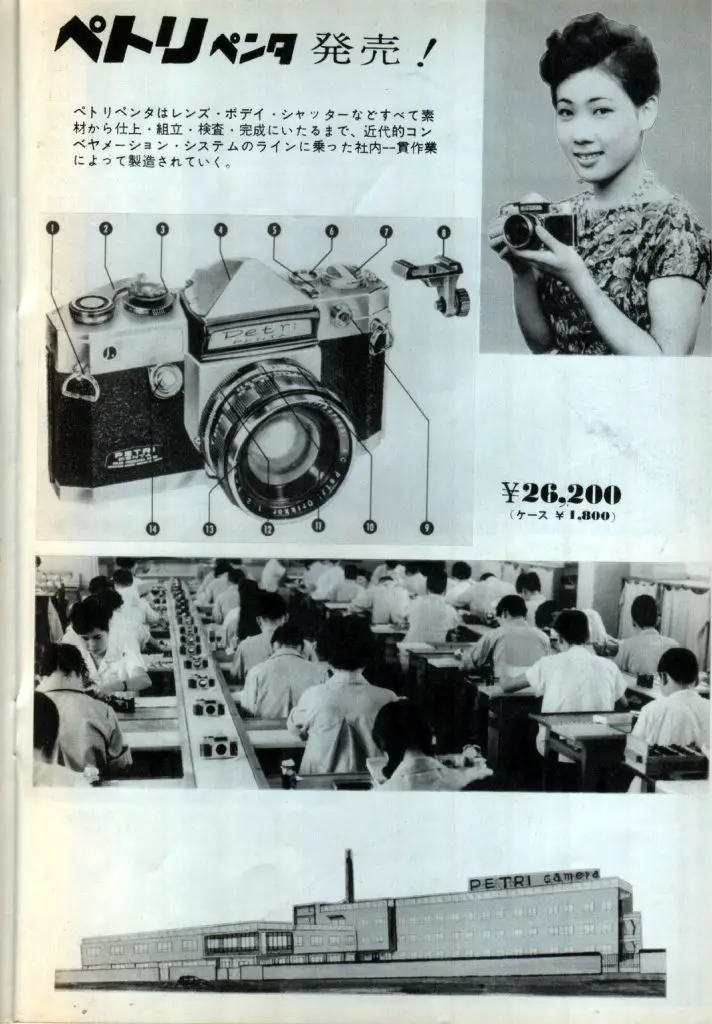

When it was released in September 1959, the Penta was marketed as having an irresistible price of $149.50, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to $1330 today.

Compared to other cameras such as the Pentax H2 at $179.50, Minolta SR-2 at $249.50, Miranda C at $279.50, and Nikon F at $329.50, the Petri was the best value in Japanese 35mm SLRs yet it still came with an excellent lens, a universal lens mount, and features like an instant return mirror, automatic resetting frame counter, and a film advance lever, all features that were still not standard on every camera.

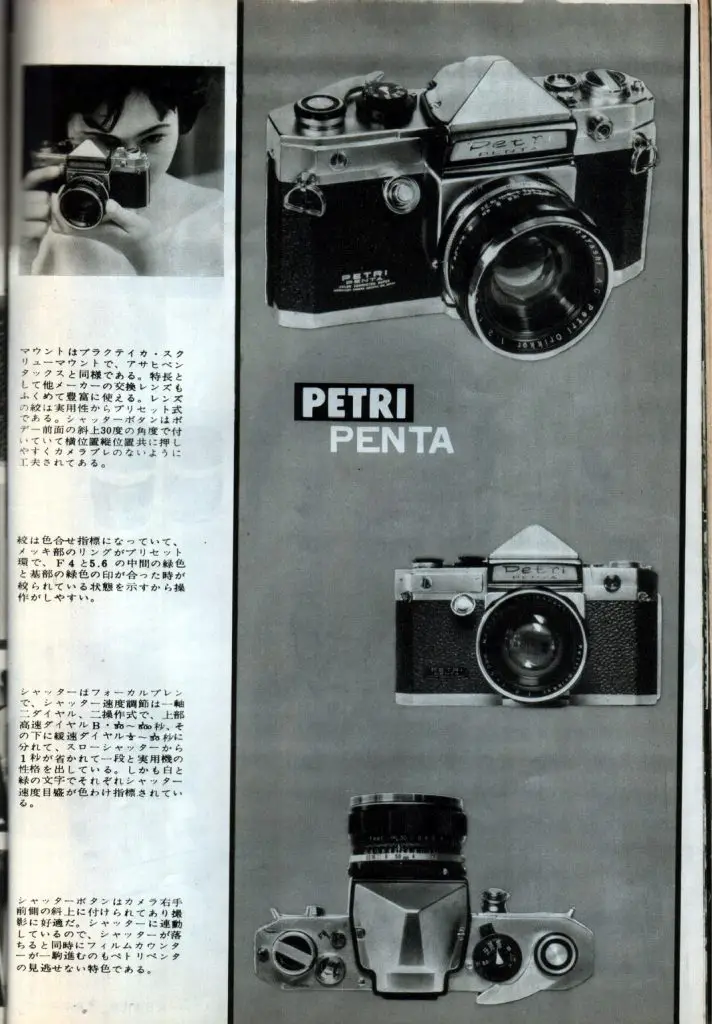

The following gallery contains scans from various issues between September 1959 and February 1960 from a Japanese language Petri newsletter called “Photo Contest”. Although I do not speak Japanese, looking through these, it is clear that a lot of pride went into these announcements, showing the camera and it’s features from multiple angles.

Curiously, the images show examples of the camera with slight differences from the one I have, which suggests that perhaps these images were of an early prototype, or that there were mid-model changes made to the camera during it’s production.

The most obvious change is in the shutter speed dial, which is a smaller, two piece design with fast speeds from 1/30 to 1/500 plus B and X on the top dial and slow speeds from 1/2 to 1/30 on the bottom. While in the process of writing this review, I was able to find the image to the right of a camera from the collection of Johnny Sisson who has the earlier shutter speed dial, suggesting that this was not only a feature of the prototype.

Other minor changes are the chrome and black design of the rewind knob, and the location of the serial number on the top plate instead of the front of the pentaprism.

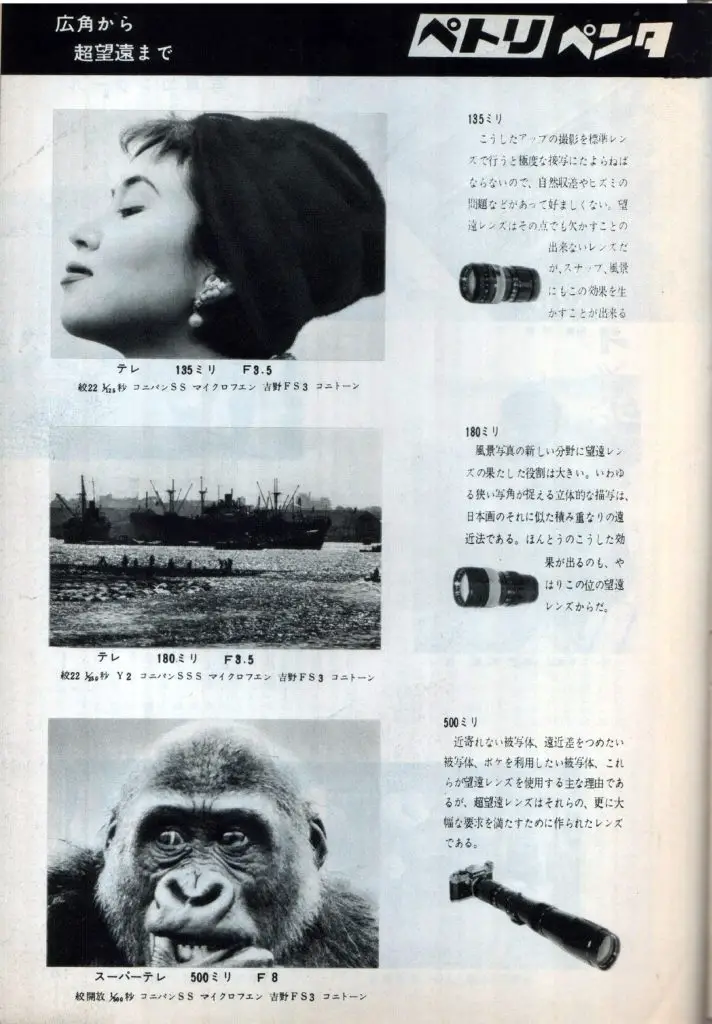

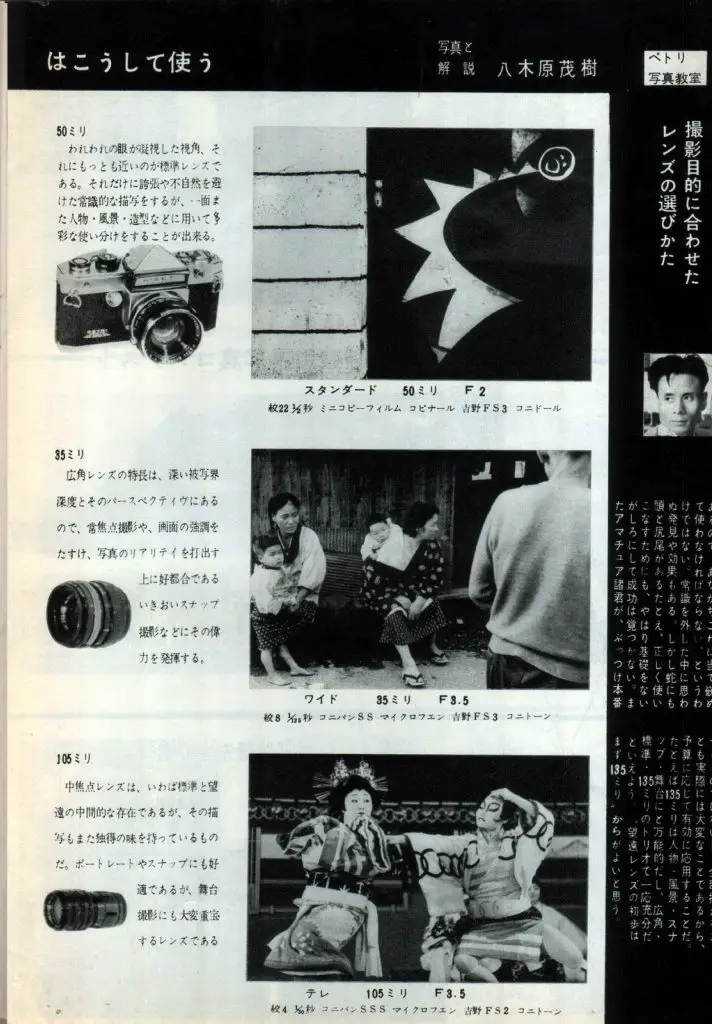

Upon it’s release, Kuribayashi had produced six lenses for it ranging from 35mm to 500mm, all using the M42 universal screw mount. The normal lens that came with it was a 7-element 50mm f/2 Orikkor. This lens design is unusual as most f/2 lenses use a five or six element design. You don’t normally see seven element designs slower than f/1.4.

The Petri Penta lacked an automatic diaphragm, so each of the six lenses were of a preset design in which two separate rings on each lens were used to select the desired stop down aperture, and a second to actually control it.

The lack of an automatic diaphragm is likely why Kuribayashi quickly abandoned the M42 screw mount and released a brand new breech-lock bayonet lens mount in 1960 with the release of the Petri Penta V. This new lens mount meant that new lenses would need to be created, but the bayonet mount allowed for lenses with fully automatic diaphragms and eventually open aperture metering.

All subsequent Petri SLRs would use this breech lock Petri mount up through the Petri FTX from 1974 which switched back to the M42 lens mount. This was done in what was likely a last ditch effort to sell cameras in an increasingly competitive market. In the fifteen years between the release of the Penta and FTX models, the camera market had changed substantially. Kuribayashi (now called Petri) had fallen on hard times both financially and found themselves as a second or even third rate camera maker whose products were often made as OEM models for other companies such as Argus, Carena, Spiratone, and others.

Today, most Petri cameras aren’t highly sought after by collectors. Petri’s poor reputation for quality has survived all these years, and most collectors see their models as inferior products with only a few exceptions. One of those exceptions however, is this Petri Penta. With a build quality above later cameras, a unique shutter system, and an excellent 7-element Orikkor lens, these cameras fetch prices exponentially higher than some later Petris, and for good reason as they’re great cameras that are fun to use and gorgeous to look at.

My Thoughts

Back in June 2016, I reviewed my first Petri camera, the Petri Flex V. I remember I bought that camera because I was drawn to it’s good looks. Since that review, I’ve reviewed several other Petri cameras such as the Racer and the Color Corrected Super. In the case of the CCS, I’ve actually owned five different models, and between those five, two Racers, and that original Petri Flex, I learned the valuable lesson that Petri cameras are some of the most unreliable out there.

That’s not to say that all Petris are junk, or that models from other companies can’t also have problems, but the odds of having a Petri camera fail on you are much higher than others, even if they appear to work when you first get them as has been the case of every single Petri I’ve ever reviewed. In fact, it took me until I got the 4th variant of the CCS that I found a camera that stayed working.

With this history of Petri cameras, why do I keep reviewing them? I’ve asked this question myself, and much like I’ve said in my repeated attempts at getting a working Miranda SLR, for some reason, I am illogically drawn to them. Japanese companies were known for making functionally brilliant, but cosmetically boring products. Comparing a Petri or Miranda to most other Japanese cameras is much like comparing a Jaguar E-type to a Toyota Camry. I guess I am a sucker for a pretty face!

I was reluctant to pick up this camera as the seller couldn’t claim to it’s functionality because they “didn’t know anything about cameras”. No matter I thought, at least the lens is there and these screw mount Orikkors usually seem to fetch a fair value that could help me recoup the cost if I decided to sell it.

When it arrived, I was pleased to see that the camera seemed to be in working order. It was musty, as many are, so I wiped it down and let it air out for a couple months waiting it’s turn to be shot.

Holding it in my hands, I was reminded at why I liked that other Petri Flex V so much. This company had a knack for making cameras that looked as good as they felt in your hands. Unlike other 1950s SLRs, the Petri Flex is compact, similar to a Pentax SLR and far smaller than Nikon, Canon, or Minolta SLRs of the day. With the lens mounted, the camera weighs a not unreasonable 803 grams, heavy enough that you won’t forget it’s there, but not like a boat anchor hanging from your neck.

The positioning of the front shutter release is extremely convenient, as are the locations of all the controls on the top plate. From left to right is the fold out rewind crank, with a flash synch lever for FP and X bulbs, and a round window with a combined automatic resetting exposure counter and ASA film speed reminder. The ASA film speeds don’t actually control anything as this is a meterless camera, but can be changed by rotating the outer ring around the window. Color speeds from 5 – 100 or black and white speeds from 50 – 800 can be selected.

In the center is the fixed pentaprism viewfinder. There is a piece of black trim around the entire perimeter of the prism which gives the look of a removable viewfinder, but otherwise is only cosmetic.

To the right of the prism is the very large shutter speed dial. This dial is one of the largest I’ve seen on a camera and gives a good amount of space between the camera’s 9 speeds plus Bulb and an X-sync speed between 30 and 60. The film advance lever is a single strong design and has an approximate 15 degree stand off before film advance occurs. From there its another 180 degrees for a single advance. The lever is not geared for several small motions so only a complete motion will complete the cycle.

The camera’s bottom is mostly barren, save for the rewind release button, and a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket which would help maintain balance when the camera is mounted to a tripod.

The overall shape of the body has angular corners, which on each front facing angle is a metal strap lug. Near the top of the left side of the camera is what I first thought was some sort of flash connection, but it is actually a screw in socket for an optional flash accessory shoe that when mounted, sits above the rewind knob. A small metal post on the top plate to the left of the rewind knob is there to help stabilize the accessory shoe when it is connected. Below the socket is the sliding release latch for the film compartment door.

The film compartment is pretty ordinary, with left to right film transport onto a fixed and single slotted take up spool. The take up spool winds counter clockwise which is said to help flatten film as it is transported onto the spool. The inside of the film door has a large metal film pressure plate with rectangular divots on it which helps reduce friction as film advances through the camera.

Normally when acquiring cameras from this era, the first thing you must do is replace the crumbling foam light seals, but thankfully the Petri Penta uses a wide felt seal on the door hinge, and black yarn seals in the film channels. In my example, all three were still doing their job and did not need to be replaced.

Also notice the brown sticker inside the door that appears to be original to the camera, stating that in the event the camera is defective, or does not function properly, it can be returned to the manufacturer for repair. The sticker makes no mention of the duration of this warranty, nor does the camera’s English user manual.

Up front we see the Penta’s M42 screw mount, which if you’re familiar with other Petri Penta cameras, looks a little strange as every Penta SLR made after this camera uses a proprietary breech lock Petri bayonet mount. Fifteen years after this camera, Petri would once again use the M42 lens mount.

Like all M42 lens mount cameras, the lenses are installed and removed “righty tighty, lefty loosey”. The Penta does not have any provision for an automatic diaphragm, so although automatic lenses by other cameras can be mounted, they will only work in stop down mode. In total, six lenses were made for the camera ranging from 35mm to 500mm, all of which had preset diaphragms.

Other than the mount, the front of the camera also has the 30 degree angled shutter release button, and a flash sync socket to the right of the logo plate. A collar around the shutter release can be unscrewed to reveal external threads for a Leica style shutter release cable. There is also a small Petri Penta logo plate in the bottom left corner, and the camera body’s serial number on the front face of the pentaprism.

The standard lens with this camera was the 7-element Orikkor 50mm f/2 lens. This lens is highly sought after as it is a unique design and one of the only f/2 or slower 50mm prime lenses with seven elements. The manual claims to have an amber-magenta lens coating that improves contrast in black and white and color films.

The Orikkor has a preset-diaphragm which was a way of setting a camera to a chosen f/stop for proper exposure using one ring, and then opening and closing the diaphragm with another. This was the only way possible to have open aperture metering on an SLR without any support for automatic diaphragms.

The benefit to this is that whatever f/stop you choose, you can still open the diaphragm while composing and focusing through the viewfinder to maximize brightness, and then quickly stop down the lens before firing the shutter without having to take the camera away from your eye. This is certainly slower than lenses with automatic, or even semi-automatic diaphragms, but was better than having nothing at all.

This is accomplished by manually rotating the silver ring with the f/stop numbers on it to your chosen f/stop, and aligning it with the red diamond on the depth of field scale. Using the previous image of the lens as an example, the silver ring is preset to f/11. But having the silver ring at 11 like in this picture does not actually stop the lens down to f/11. Stopping it down is done in a separate step by aligning the black ring with the green triangle closest the lens mount, to the green trapezoid shape in between 5.6 and 4 on the silver ring. Only when the green triangle and green trapezoid are lined up, is the lens properly stopped down to whatever number on the silver ring is beneath the red diamond. This sounds really confusing reading it from a screen, and it’s not exactly intuitive for the first time user, but it does get simpler with repeated use.

The viewfinder uses a ground glass with Fresnel pattern to improve edge and corner brightness outside of a large ground glass circle. There are no split image or microprism focusing aides on the camera, although with the f/2 lens wide open, is reasonably bright, making focus in everything but the lowest light possible. In the images above, I was able to take both an in focus and out of focus image through the viewfinder using my cell phone, in a room with only ambient light. Although I would have preferred a split image focus aide, or at least a microprism circle, the viewfinder is bright enough to where it’s usable in most lighting situations. Being a completely mechanical camera, there is no meter readout or any exposure settings visible within the viewfinder.

Petri cameras don’t enjoy a positive reputation by collectors today, especially their SLRs. This original Penta seems to be one of the few exceptions as it’s got a clean interface, it’s much more compact than most other SLRs of it’s era, and it came with an outstanding lens. Even without putting a single roll of film through it, the instant you pick it up, it is clear this is a comfortable camera to hold and would likely be a pleasure to shoot, but was it? Will this Petri Penta live up to Petri’s poor reputation, or is this camera the exception that sold prices on eBay make it out to be?

My Results

When it came time to shoot the Penta, I went through a normal sequence of tests that I give any camera I’m about to shoot for the first time. A majority of cameras I pick up are often in “as/is” or otherwise untested condition. Unless it’s a loaner sent to me by another collector, I never handle cameras that have been professionally serviced, so encountering operational issues comes with the territory.

The Penta seemed to be in good condition, the shutter fired at what looked to be all the correct speeds, the viewfinder was clear, and all of the camera’s other motions seemed OK. I loaded in some bulk Kodak TMax 100 and shot a quick roll.

After seeing the first few images, it became clear the camera’s shutter had issues. As I was out with it, I noticed the shutter failed to fire about 25% of the time and in instances where it did, after inspecting the negatives, I could see that one side was darker than the other suggesting the timings were off. It has been my experience with shutters from all brands of cameras that this type of issue will not go away on it’s own, and in most cases will continue to get worse.

Unwilling to invest the money in a CLA, but with a desire to still review this camera, I removed the Orikkor lens, mounted it to an Asahi Pentax Sv and shot a second roll of Fuji 200. I figured that since I really did shoot the Penta with the first roll, I can still comment on it’s use, and with the M42 lens on a known working body, I could separately comment on the quality of the lens.

I have never had any doubt of the optical performance of Kuribayashi/Petri lenses as I’ve gotten consistently great results from cameras like the Color Corrected Super “Green-O-Matic” and Kuribayashi Karoron, so I wasn’t surprised to see a fully gallery of images that were perfectly sharp from corner to corner, exhibiting excellent colors and good contrast. The 50mm f/2 Orikkor is as good as any other quality 50/2 Takumar, Nikkor, or Rokkor lens from the era.

The camera itself is an interesting mix of good and bad. In terms of the good, considering the era in which the camera was built, it is clear Kuribayashi took a cue from Asahi Optical with their Pentax cameras in designing a more compact body with excellent ergonomics. The shutter release is comfortably located on the front of the camera at an angle, much like that of a Praktica SLR.

Unlike the large and heavier Nikon, Topcon, and Minolta SLRs that were common at the time, the Penta has a size and weight more in line with Pentax, and later Olympus SLRs. With a body only weight of 607 grams, the Penta is very easy to carry for extended periods of time.

I also found the camera to be pleasantly quiet in it’s operation. The sound of the shutter firing, combined with the mirror cycling up and down is quite a bit more subdued than other SLRs of the era, and even those that would follow. It would not be until the Olympus OM-series that a company made a concerted effort to dampen the sounds of the shutter in the interest of reducing it’s noise. I do not know what effort, if any, Kuribayashi employed to make the shutter so quiet, but their use of a unique torsion spring for tensioning the shutter may have had a hand in this.

The viewfinder is what I would call “good enough” with only a large ground glass circle in the center, surrounded by a Fresnel pattern to improve brightness. It is disappointing to see any other kind of focus aides such as a microprism collar or split image rangefinder, but I cannot put too much fault in this as this was standard fare in 1959.

Although using the M42 screw mount, which would have meant that a huge variety of German and Japanese lenses would have been compatible with it, the Penta lacks support for an automatic diaphragm, which means that only preset lenses can be used. Perhaps this foreshadowed Kuribayashi’s decision to abandon the screw mount the very next year and switch to a unique breech lock bayonet mount which did support automatic lenses.

Back to the shutter, with available speeds of 1/2 to 1/500, there is neither a 1 second or 1/1000 top speed, which for most people wouldn’t be a deal breaker, but even in 1959 would have been a sign of a camera that was aimed at the lower end.

From the standpoint of it’s design, ergonomics, and features, I don’t have any serious complaints, and I can see how someone in the market for a mid range 35mm SLR in 1959 might be interested in this model, especially at it’s $149.50 price. It had a good selection of modern features like an instant return mirror, automatic resetting exposure counter, a lens mount that allowed use of a wide variety of already available lenses, a good but not spectacular reflex viewfinder, and gorgeous cosmetics.

We wouldn’t know until years later that this model would be plagued with reliability issues or that Kuribayashi, shortly after changing it’s name to Petri would struggle both financially and with their build quality, eventually becoming a third rate OEM supplier of cameras.

Perhaps the most appealing attribute about the Petra Penta for collectors today isn’t the camera itself, rather the screw mount Orikkor lens that it came with. To the best of my knowledge, this is the only 7-element in 4-group f/2 lens made by any company and whether or not that translates into a measurable improvement over other 6-element designs, I can’t say for sure, but it is clear to me that this lens is very good.

The gallery above is of images using the Orikkor lens adapted to digital. A combination of excellent sharpness and extremely smooth (some people would call it creamy) out of focus details give images shot with this lens a distinct look. The best way I can describe it is that it blends the sharpness of a modern digital lens, with the rendering characteristics of a vintage lens. In the two images of the purple crocus, one is shot at f/8 and the other wide open at f/2. Notice how the f/2 image has an almost painting-like look to it. Is the Orikkor a perfect lens to adapt to digital? I’ll let someone who is more skilled at lens tests make that determination, but I can say that in my unscientific opinion, it does a very good job.

The Petri Penta is a curious camera and one that I am very happy to have in my collection. Despite having the conditional issues I had with this one, I won’t really fault it other than to say that if you are looking for one to add to your collection, don’t get your hopes up too high in terms of using it. This is a very cool and gorgeous camera that came with a terrific lens that is easily adaptable to any other M42 camera, and is equally worth considering for it’s excellent ergonomics, quiet operation, and excellent lens.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Petri_Penta

https://w.atwiki.jp/petri/pages/20.html

http://www.pentax-slr.com/181841703

http://www.topgabacho.jp/PETRI/Vseries/Vseries.htm

Nice and informative review, as usual. I never thought much of Petri cameras, except for the wonderful, tiny Color-35 model. That lens looks like a keeper, though.

Your explanation of the shutter tensioning mechanism is very interesting: An unusual way to accomplish the task. Once I had a 50mm f1.4 Orikkor lens in Petri’s later bayonet mount. I have seen exactly one of these over five decades. It does not exist as an option in Petri’s advertising of the era. I wonder if anyone reading this has seen this lens?

Mike, when I was looking for a 35mm slr (my first) to supplement my Yashicamat in 1965 for slides, I was looking at a used Penta, among others. I assume now it must have had the f2 Orikkor although I can’t remember. I was 20 at the time and my regular photographic shop dissuaded me on the grounds of reliability, no doubt thinking of my finances! Instead, I purchased a “Reflexa” badged camera which he told me was actually a Mamiya, and this came with a semi-auto Canon f1.9 50mm lens in Exakta mount, and never regretted it. Wonderful lens with Ektachrome.

Perhaps reliability really has been an issue with Petri cameras. No Penta at all on ebayuk and many later models listed as faulty. Either reliability has caused the dearth, or the better ones have been snapped up already.

This said, the Orikkor lens on your Fuji digital looks excellent, especially the shot of the hydrant. But the flower closeups don’t look as impressive. Is this focussing, or is the lens not happy with near field subjects?

I wonder if you still have that Reflexa with the Canon lens as I’m sure you’re aware they’re quite rare. That is the only Canon lens ever made for the Exakta bayonet mount and the reason for Canon making it as they were also at the time in contrast talks with Mamiya to build the Canonex leaf shutter SLR for them and that lens came out of an agreement that the two companies made.

As for the digital flower pics, to me, they look very good, but the difference you’re seeing could be that the M42 -> Fuji X-mount adapter also has it’s own helicoid in it, allowing me to close focus the lens much closer than it was intended. Those images were shot less than a foot away from the flowers, something the lens couldn’t do on it’s own. Perhaps shooting it so close introduced some optical characteristics that it wouldn’t normally have.

Hi, Mike. I still own it and some years back I added a second! And and a couple of years ago i found a mint 100mm lens. I always wondered why it was Canon supplied the lens for a re-badged camera, and specifically in the European Exakta mount, as it affords no advantage over M42, being a “dumb” mount with all the lens operations being external to it.. By the time of the camera’s release, c.1961, you couldn’t say the lens mount or lenses were that popular, save for Exakta users, given the unique body/lens relationship. And the lens, and original Exakta lenses, aren’t interchangeable between bodies. Welcome the T-mount, albeit the lenses have to be PD.

The Canon diaphragm release mechanism is to the right of the lens mount, whereas as you know Exakta lenses release on the left. Also, the spring diaphragm release pin on the Reflexa is actuated from the camera, but with conventional Exakta lenses, the lens release pushes in the shutter release on the body. The present day problem with the Canon lens is with Digital camera lens adaptors for Exakta lenses. These adapters, as they are machined with original Exakta lenses in mind, don’t allow the canon lens to be physically attached because the diameter of the adapter that protrudes beyond the mount is too wide! I happened upon one where I could see that the mount was machined at a slightly sloping angle with the diameter decreasing towards the mount. I took a gamble and purchased one and I was right, it did allow me to mount the Canon. The problem is the diaphragm release mechanism and which, in the Canon, fouls the other mounts, physically preventing the lens from being attached.

As for the camera, the story goes, as I understood it at the time, that it was primarily aimed at the UK market. I don’t know why, but I did read something about this a long time ago. Incidentally, both the shutters on mine, still fire smoothly and the curtains are still light-tight. Not bad, considering they are around 60 years old.

Ooops, forgot to comment on the Orikkor lens used close up. From the additional info you have provided, I’m fairly confident know that the image softening is down to the close focus. Most slr lenses of that era probably limit the close focusing distance to around .5m or 20inches or so. Standard lenses aren’t computed for closer and will suffer IQ, which I am seeing with the flowers. Look at the stamen in the purple flower. Very soft. There is a significant image degradation in the flowers compared with that ultra sharp hydrant. The simple way to overcome the problem, up to a point, and not wanting to invest in a proper macro lens, is to use a reverse lens adapter.

I was always interested in the story of Petri. When I was in high school (68-72), and we were all getting into photography, most of us were using a selection of cheap eastern euro cameras we could pick up on the fly, like the Praktina FX. A buddy bought a Petri model new, which seemed pretty “finished” compared to what we were using. I know he was getting good results from it, but I ran into him a few years after high school and he said the camera body was “dead”, with no local repair guys interested in fixing it. I know at the time he bought it, you could have put the Petri on a counter top with a Pentax, Mamiya and Minolta, and it wouldn’t have seemed out of place! It was never really widely known, tho. It wouldn’t have been an obvious choice to buy

BTW, I also have a “jones” for Miranda! My first “pro-level Japanese Camera” was a Sensorex, which I adored. It developed a shutter problem shortly after buying new (luckily I lived near the importers repair station in the Chicago area), and the problem was it wouldn’t set the curtain slit, it would just stay shut, so you’d get a whole blank roll without ever hearing anything that made you think it was off! It was actually a systemic problem and I was told it was fixed in the later series Sensorexes, and gone in the Sensorex 2, but by that time, I had started my career and worked at studios that were all Nikon, so bought in to borrow the lenses. I own 2 Sensorex bodies and a few lenses today, one fixed to perfect (for a while), by Essex camera, the second, not so much. Essex camera was swept away in a hurricane before I could get it in for repair! Any Miranda repair experts out there, let me knoow….

I’ve spent copious amounts of time working (ultimately unsuccessfully) on my Penta. The torsion spring in the bottom of the camera isn’t related to shutter timing. It is used to lift the mirror prior to shutter operation, and then to also return it after the shutter has closed again. The mirror lever is connected to the end of that shaft. The shaft is in two parts, with the torsion spring being first wound up by one half of the shaft, before transmitting the turning force to move the mirror lever connected to the second part of the shaft. The mirror lever when lifted, latches on another lever which is manipulated by the second shutter reaching its closed point. The shutter timing is reasonably conventional, with the slower speeds being accomplished with a geared delaying mechanism just like those found in a leaf shutter.

Good info Alun! I wish my Penta worked as good as new, but it didn’t. I guess if I really wanted to mess with it some more, I could spend more time figuring out which speeds are less likely to cap and just shoot it at those speeds, but for now, it will remain a shelf-queen and if I get a desire to shoot the Orikkor again, I’ll just do like I did in this review and mount it to another M42 mount camera.

Any chance you’ve run across a diagram or explanation of how to break the lense down? I just picked one of these up and the lense needs a good cleaning, but I can’t find a break down anywhere.

Sorry, I have not. Opening lenses to clean them is beyond my ability and something I do not recommend to someone unless they have experience with it. Good luck!