What is it?

This is a Praktina FX 35mm single lens reflex camera made by Kamera-Werke Niedersedlitz (KW) between the years of 1953 and 1958. The Prakina and all of its variants are historically significant cameras, being the first modern 35mm SLR camera aimed at the professional photographer. It had advanced features such as an interchangeable viewfinder, focusing screen, and lenses, a 1/1000 top shutter speed, and a provision for a motor winder. Furthermore, a huge number of accessories, including an interchangeable magazine back that allowed a 50 foot roll of film to be installed. The Praktina was a very robust “system” SLR that served as inspiration for many professional cameras like the Nikon F and Canon F-1.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Tessar coated 4-elements

Lens Mount: Praktina Breech Lock Bayonet

Focus: 1.65 feet / 0.5 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Prism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: PC port F and X flash sync

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/praktica_pdf/praktina_fx.pdf

History

The Praktina was a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made in Germany by Kamera-Werke Niedersedlitz (KW) in the 1950s and has a name that is very similar to another KW made 35mm SLR, the Praktica. With only one letter difference in the two camera’s names, they often get confused for each other, but they are in fact quite different cameras. Other than the similar name, Praktina and Praktica SLRs have completely different lens mounts, have many different features, and were developed for totally different types of photographers. This review is for the KW Praktina FX, made between the years of 1953 and 1958, not the KW (later Pentacon) Praktica that was in production for much longer.

KW’s Early Years

KW was founded in Dresden, Germany in 1919 by Paul Guthe and a Swiss businessman named Benno Thorsch as Kamera-Werkstätten Guthe & Thorsch. Guthe had previous experience in camera manufacturing, owning another camera factory in the Dresden area that he founded a few years earlier in 1915.

KW’s first product was a folding camera called the Patent Etui. It had an extremely slim and compact body that was quite a bit smaller than comparable cameras of the time. The word “etui” in German translates to “case” in English. There were versions made for 6.5cm x 9cm sheet film and some that used 9cm x 12cm film. The Patent Etui had an innovative and unique design that was unlike any other camera made at the time, or even in the years that would follow. This innovation would become a hallmark of KW’s legacy, setting a standard for new and unique designs and features in many of their models to come.

The Patent Etui was in production throughout the 1920s at a time when the German economy was very weak due to the outcome of World War I. Many German companies would either collapse or merge with other companies during the 1920s. In 1926, four Dresden area companies would all merge together to form one single company that would be called Zeiss-Ikon. But not KW, they were one of the few Dresden optics companies that saw great success. So much so that in 1928, KW moved from it’s original location in Niedersedlitz to a larger facility in Dresden, right down the street from Zeiss-Ikon’s factory. KW employed at least 150 employees and the company’s output at this time was around 100 cameras a day.

In 1931, KW released another innovative camera with an all new design called the Pilot Reflex. This new camera was a folding Twin Lens Reflex design that took 3cm x 4cm images on “Vest Pocket” 127 roll film. The Pilot Reflex combined the best features of a TLR like the Rolleiflex and a folding camera that when collapsed was much smaller and portable. A few years later, KW would release two more Pilot models known as the Pilot 6 and Pilot Super, both were medium format Single Lens Reflex cameras that used 120 format roll film.

Note: A large amount of the information from the next few paragraphs comes from an excellent essay on KW’s history written by T. Rand Collins MD on his blog, “Through a Vintage Lens”. I will do my best to paraphrase the relevant facts here in my own way without plagiarizing the original author’s work, while still giving him full credit for the research.

Note 2: These next few sections focus on the lives of the people behind KW, rather than the cameras they made. If you are only interested in information about the Praktina itself, skip down to the section called “The Praktina Years“

World War II

At the time of KW’s greatest success, Paul Guthe and Benno Thorsch who were both Jewish, started to feel the pressure of anti-Jewish treatment in Germany and in 1938, would flee the country. Guthe was the first to leave, selling his shares in the company to Thorsch. Very little is known about what happened to Paul Guthe after he left Germany, but Benno Thorsch’s story on the other hand, is quite fascinating.

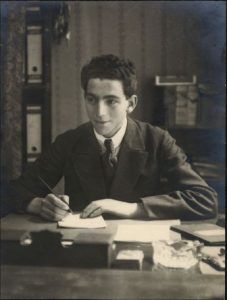

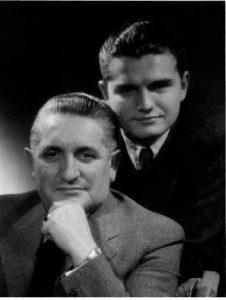

Before leaving Germany, Benno Thorsch befriended a German born American businessman named Charles A. Noble (born Karl Adolf Spanknöbel) who owned a failing photo-finishing company in Detroit where his wife worked. Thorsch would negotiate a mutually agreeable trade of KW for Noble’s failing company back in the United States. Benno Thorsch quickly left for America to run his new business while Charles Noble’s family moved to Germany to take over KW. Together with his son John, in 1939 Charles would rename the company to Kamera-Werkstätten Charles A. Noble.

Benno Thorsch would revive the Noble’s struggling film finishing business in Detroit, but would ultimately relocate out west and in 1944 would open the Studio City Camera Exchange on Ventura Boulevard in North Hollywood, CA. Benno would run the business with his son Bennie, and eventual grandson Ronald for 62 years until it closed in 2006. Benno Thorsch would live a long life, eventually passing away in a retirement home in 2003 at the age of 105.

The Noble Years

The Noble’s story however, went in a different direction. Upon resuming business operations in 1939, Charles Noble felt that 35mm Single Lens Reflex cameras were the way of the future and would hire German engineer Alois Hoheisel to help design KW’s first 35mm SLR camera, which would eventually become the Praktiflex. The Praktiflex made it’s debut at the 1939 Leipzig Fair and would generate excitement almost immediately. Demand for the new Praktiflex was so great, that the company had to quickly relocate into a former candy factory in Niedersedlitz to meet demand.

War would break out shortly after the release of the Praktiflex and the Nobles would attempt to return to America, but would be denied exit and required to return back to Dresden where they would resume operations at KW. Unlike many other manufacturing companies in Germany during World War II, it appears that KW was allowed to continue making cameras throughout the war as there exist cameras made between 1940 and February 1945. In fact, at least one variant of the original Praktiflex was made for the German military. Military issue Praktiflexes were engraved with “M 309” on the bodies and all lenses associated with it. Whether KW also produced other, non-optics products for the German war effort is unknown.

In four separate bombing raids on February 13th, 14th, and 15th, 1945, Allied bombers unleashed an unprecedented attack on Dresden, likely because of it’s manufacturing and transportation capacity. 722 bombers from the British Royal Air Force and 527 from the United States Army Air Forces dropped a combined 3900 tons of bombs and incendiary devices on the city. The “shock and awe” firestorm resulted in the complete destruction of over 6.5 square kilometers of the city’s center and a widely disputed number of deaths. Some German sources at the time claimed that between 200,000 and 500,000 people died in the attacks, but a 2010 study by Matthias Neutzner suggested a number closer to 25,000 was more accurate. Whichever number is correct, the bombing of Dresden has become a point of contention and controversy that continues to this day due to the apparent overkill of the mission.

The KW factory was spared total destruction, likely because of it’s location in nearby Niedersedlitz, as opposed to the city center like most other optics companies of the time. Praktiflex production would resume after the Dresden bombings for at least another year.

Dresden is located in what would become Soviet controlled East Germany. Upon occupation of Soviet forces in Dresden, KW would become a state owned entity known as VEB Kamera-Werkstaetten Niedersedlitz. The abbreviation VEB stands for Volkseigener Betrieb which translates to ‘Publicly Owned Operation’ in English and was the main legal form of industrial enterprise in East Germany from the late 1940s until the early 1960s.

KW had been successful at making all of their own camera bodies, but they never made any of their own lenses. The lenses were all sourced from Carl Zeiss Stuttgart and Schneider-Kreuznach, both companies who were located in the western part of Germany, which after the war would become Allied controlled West Germany. As a result of the new alignment of the two separate countries, KW needed to re-negotiate a deal with Zeiss in order to buy lenses for future KW cameras. In 1946, after considerable negotiations with the Soviet government, Charles and John Noble were granted permission to travel to West Germany to formulate an agreement for them to continue purchasing Zeiss lenses.

Prison

Upon their return to Dresden however, both Charles and John Noble were arrested under unfounded suspicions of espionage and sent to prison camps in the Soviet Gulag system. The conditions in the forced labor camps were abysmal. Starvation and executions were common practice, and both Nobles relied on their religious background to stay alive. Charles and John were kept together in the same prison camp until 1950 when John Noble, who was 26 at the time, was given a 15 year sentence and sent to a variety of different Soviet prison camps, one of which was the Soviet Special Camp No. 2 which was formerly the Nazi Buchenwald concentration camp. Noble would eventually wind up in town called Vorkuta in northern Siberia where he mined coal with over 100,000 other prisoners.

In 1952, Charles Noble would be released from prison, never to return to KW or Dresden again. He would at first live with relatives in West Germany, but eventually make his way back to the United States where he worked as an adviser to the photography department of General Motors. He would die in May, 1983 at the age of 90.

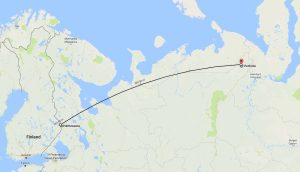

John’s situation however, was much worse. Conditions in the Gulag camps were beyond bad. The town of Vorkuta where Noble worked is located within the arctic circle and average winter temps don’t get any higher than -20°C, with occasional drops to as cold as -52°C. Death among the prisoners from starvation and freezing were common. To cope, prisoners would huddle together at the bottom of coal pits in an effort to salvage any body heat they had. Years later, John Noble would say that during his stay in Vorkuta, he weighed less than 100 lbs as he was kept on a starvation diet for months at a time.

In the early 1950s, John’s whereabouts were unknown to his family and multiple requests to the state department yielded no answers. Then in July 1953, shortly after Stalin’s death, in a twist that seems like it should have come straight from a Hollywood action movie, John Noble took part in an uprising among prisoners from multiple Gulag labor camps.

Somewhere around 400 prisoners would take over four different camps staging an escape, and then embarking on a nearly 1000 mile walk towards Finland. A month after their escape, the prisoners would be caught, and for their crimes, most would be executed. Somehow, John Noble would be spared execution and sent back to prison.

A year later, Noble would manage to sneak a postcard addressed to his family by gluing it to the back of some other mail that was being sent out. The postcard would manage to make it’s way to some of Noble’s family living in West Germany who then notified the U.S. Government of his location. Since John Noble was born in Detroit, MI before his family purchased the KW factory from Benno Thorsch, he was an American citizen and this prompted the Eisenhower administration to contact the Soviet government and demand his immediate release.

In January 1955, along with several other American POWs, John Noble would be released after nearly 10 years in prison for a crime he never committed.

Redemption

After his release, John Noble would first give several press conferences in West Berlin, detailing his experiences and the horrific treatment he and other prisoners suffered at the hands of the Soviet Gulag system. Three days after his conference, in an attempt to discredit Noble and his family, the East German government would issue a statement in their national newspaper making the absurd accusation that John’s father Charles helped coordinate the Allied attacks on Dresden in February 1945.

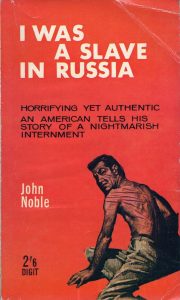

Shortly after, Noble would return to the United States, giving multiple lectures about his time in prison. He felt he had a duty to tell his story about the consequences of dictatorship and the contempt for humanity which he suffered. In 1958, he would publish a book called “I Was a Slave in Russia” which was a best seller at the time, selling nearly 1.6 million copies upon it’s release.

John Noble would spend the next several years as a speech writer and political consultant in the United States. He became a beacon of hope for human rights, and helped to raise awareness of other prisoners in Soviet camps. In 1979, he was knighted for his persistent and tireless efforts towards the benefit of humanity by the French Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem.

After the reunification of Germany in 1990, Sir John Noble would return to Dresden and attempt to reclaim the rights to his father’s old company. Although unsuccessful at attaining KWs patents or the Pentacon name, he would be awarded the property of one of KW’s factories in Dresden where he would relaunch KW as Kamera Werk Dresden. In 1992, a new series of panoramic cameras called the Noblex were produced with versions using 35mm and 120 roll film. The cameras were quite successful and seem to have been produced until recently. As of the writing of this article in November 2017, the Kamera Werke Dresden website seems to be down, so I am not sure if they are still in business.

Sir John Noble would continue to give lectures on talk shows, schools, and at other public speaking events up until his death on November 10, 2007 (I want to point out that as I type this, it is November 9, 2017, one day before the 10th anniversary of Noble’s death). He was survived by his wife, 5 children and 9 grandchildren. His body was buried at the Waldfriedhof Weisser Hirsch cemetery on the edge of a large foresty area near Dresden.

I realize this is a camera blog, and I went way off topic here into a dark period of humanity’s history, but as I was writing this, trying to tell the story of the KW factory and the people behind it, I couldn’t help myself but to be absolutely fascinated, embarrassed, infuriated, amazed, and a whole slew of other emotions over this story. What appears above is just a summary of an even larger tale. If you would like to read more about John Noble and some of his history, there is a lot of information at the obvious sources like Wikipedia, but here are a few other websites I found while writing this article that have even more great information too:

http://throughavintagelens.com/2009/08/every-camera-has-a-story-kw-the-patent-etui-and-john-h-noble/

http://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/wie-man-die-hoelle-ueberlebt.984.de.html?dram:article_id=153317

Finally, there is this short YouTube documentary that gives a preview to both a film and a book written by Noble in 2005, called Verbannt und Verleugnet (Banished and Vanished).

Warning, this video has some pretty gruesome images in it.

The Praktina Years

The Praktina was designed at VEB Kamera-Werkstaetten Niedersedlitz by a man named Siegfried Böhm. Böhm was a German born technical draftsman who in 1939 at the age of 18, went to work as a technician for Zeiss-Ikon AG in Dresden. There, he learned how to design and build 35mm cameras under the Zeiss leadership. In 1945, Böhm would return to Zeiss and continued to impress upon the leadership his efficient methods at improving on the pre-war designs that the company had resumed making.

After the war, the KW factory in Niedersedlitz was the only German optical factory not damaged by Allied bombing raids during the bombing of Dresden in February, 1945. The factory would continue making it’s pre-war Praktiflex SLR through the end of the war and beyond. Shortly after the Soviet Union’s occupation of East Germany, in late 1945 the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD) set an annual production goal of 50,000 cameras by the KW factory, a number that was unattainable largely due to the hand crafted precision parts required for their cameras.

In January 1946, SMAD would transfer Siegfried Böhm from the Zeiss factory in Dresden to KW in an effort to help improve the speed and efficiency of it’s output so they could meet their lofty goals. Böhm’s first changes involved a simplification of the Praktiflex’s design and a switch of the lens mount from a proprietary M40 to an all new M42 design. The revised camera was called the Praktiflex II and could be made faster and cheaper than the original model.

In addition to the revised Praktiflex, in 1949 Böhm introduced a completely new model called the Praktica which was similar to the Praktiflex, but had more modern controls, a simpler shutter, and could be sold at a price that was within the reach of most amateur photographers. The Praktica was an immediate success, helping to reestablish KW as a premiere maker of German built 35mm cameras. The Praktica name was used on a huge variety of 35mm SLR cameras over the course of the next several decades.

The Praktica was a huge hit with amateurs, but KW wanted to appeal to the professional as well. Up until this point, the only option for a professional photographer who wanted a 35mm camera was the Ihagee Exakta. Although the Exakta was a great camera, it had awkward controls and a design that was already nearly 2 decades old, so Böhm began work on an all new top of the line modern 35mm SLR aimed at the professional photographer.

Böhm’s new camera would be called the Praktina, and it was an all new design borrowing almost nothing from the Praktica and earlier Praktiflex. Aside from a similar shape, size, and right hand controls, the Praktina looked almost nothing like the Praktica, but instead resembled the Contax D/Pentacon camera made by Zeiss-Ikon. Perhaps it was Böhm’s familiarity with post war designs at Zeiss that prompted him to share some of the same design cues from his former company.

Gone was the M42 screw mount and in it’s place was an all new breech lock bayonet lens mount. The breech lock was considered superior to a standard bayonet mount because the lens does not turn when being mounted, plus it is more secure, allowing for larger and heavier lenses to be used. To mount a lens, you line up two dots on the lens and the body and then rotate a collar on the camera body to secure the lens. The advantage was that since the surfaces between the lens and camera never move, there is no chance that over time the tolerances could change, negatively impacting focus accuracy.

The Praktina had both a straight through optical viewfinder and a fully interchangeable viewfinder and focus screens, a first for any 35mm SLR. The reason for having both types of viewfinders was to improve usability in low light, and give a sort of “sports finder” for fast action shots, regardless of which viewfinder was mounted.

The camera had many other changes, including:

- More advanced 11 speed shutter with speeds from 1 second to 1/1000 compared to the Praktica’s 8 speed shutter that went from 1/2 to 1/500 seconds.

- Single shutter speed selector, with both fast and slow speeds on the same dial.

- Motor wind provision allowing for electric or spring wind film advance, a first of any camera in the world.

- Removable film back with optional accessory backs such as a bulk magazine back allowing for up to 450 images to be taken on a 50′ roll of film.

- Larger and more ergonomic front shutter release, threaded for a cable release.

- In the case of the Praktina FX, an automatic diaphragm that allows for open aperture composition.

- Many internal changes and to improve quality and durability.

In addition to all of the features above, there was a wide variety of wide angle and telephoto lenses available, a bellows extension unit for closeup and copy photography, stereo photography adapters, 3x magnification viewfinders, various flashes, and many more.

The Praktina made it’s debut in prototype form at the Leipzig Trade Fair in September 1952. The original prototypes did not feature the Praktina name but rather had a blank name plate. In total, there were 5 distinct variants of the original Praktina prototype, suggesting that the camera was in a constant state of update even after it’s public unveiling. There doesn’t seem to be any indication of how many of each prototype was made, and although they were never sold to the public, some have managed to make their way into private collections, suggesting that at least a few of each were made.

The Praktina would be officially called the Praktina FX upon it’s official release one year later at the 1953 Leipzig Trade Fair and would feature the ability to support open diaphragm lenses. This means that while composing your image, the lens stays wide open regardless of which f/stop is selected on the lens and only moments before firing the shutter will the lens stop down to the chosen setting.

In a full review in the March 1957 issue of Modern Photography, Herbert Keppler remarked at the build quality of the Praktina and the vast array of accessories available. He was most impressed with the spring motor winder saying that it was the most useful accessory, turning it into the world’s first motorized 35mm camera. The whole tone of the review was positive, and he concluded by saying:

…the camera is a step in the right direction. It is of professional quality and quite suited to professional work. It seems rugged enough to withstand much abuse. With the multitude of accessories available and those which are bound to be available in the future, the Praktina FX opens many new vistas on the photographic horizon for both professional and amateur alike.

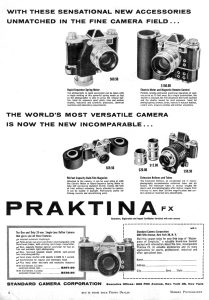

Interestingly, an estimated 60% of all Praktina models were exported out of Germany, with many making their way to the United States. In the US, a New York based importer called the Standard Camera Corporation often ran ads in photo magazines championing the features of the Praktina. The price in 1956 for a Praktina FX with a Zeiss Biotar 50/2 lens was $297.50 and $239.50 with the Tessar 50/2.8. When adjusted for inflation, those prices are like $2729 and $2197 today.

Identifying an export version of the Praktina is pretty easy as there are several markers, the most obvious of which is the glued on KW logo to the right of the viewfinder as seen in the image to the left. Alberto Taccheo’s Praktina site has a complete list of all of the other markers that identify an export Praktina.

The gallery below shows 4 ads between the years of 1956 and 1957, all from the Standard Camera Corporation in New York for the Praktina.

The prices seemed to come down by 1960 as some advertisements from that era had the camera as low as $149.50 with the Biotar lens and $139.50 with the Tessar. A considerable bargain despite the camera being nearly 8 years old at that point.

The Praktina FX would go through 5 different generations throughout its production from 1953 – 1958 continually evolving along the way. A total of just under 67,000 Praktina FXs were made during it’s 6 year production run. There were even a few rebadged models sold in various markets with names like the Corbina, Hexacon Supreme, and Porst Reflex. A comprehensive list of the changes between the sub-models and variants can be found at Alberto Taccheo’s Praktina System website.

In 1958, a new model called the Praktina IIa would be released which would be an evolution of the 5th generation model offering several internal improvements, along with a few minor external ones, but the two models were largely the same. Once again, Alberto Taccheo’s site is a good resource for more information on the differences.

The Praktina IIa would cease production in May 1960, most likely due to a variety of factors including dwindling demand, the onslaught of the Japanese camera industry, and the general population’s desire for more advanced and less expensive cameras. Despite the regular refinements to the Praktina’s design, the camera was still expensive and complicated and there simply were better options out there.

There are unproven rumors of a new “Praktina Model 1961” that appeared in some German trade magazines in 1961, but no such model was ever developed. It wouldn’t take a huge stretch of the imagination to think that there was plans for more advanced models before it’s discontinuation in May, 1960, but since it never happened, one can only imagine where the Praktina might have gone had it’s production continued.

It’s worth noting that in 1964, after VEB Kamera-Werkstaetten Niedersedlitz would be merged with nearly every other Dresden area camera manufacturer to create VEB Pentacon Dresden. A prototype model bearing the name Praktina N was shown around the trade show circuit that used the M42 lens mount, but offered through the lens (TTL) metering, interchangeable viewfinders, a provision for a motor winder, and interchangeable backs. Upon it’s release, the name of the camera would be changed to Pentacon Super and was in production from 1968 – 1972.

VEB Pentacon Dresden would eventually claim every other Dresden area camera manufacturer including Zeiss-Ikon, Ihagee, Altissa, Belca, Welta, Certo, Meyer-Gorlitz, and many others. It would continue on as Dresden’s only camera manufacturer for the next several decades, discontinuing most of the models of the companies it absorbed with the exception of the M42 mount Praktica SLR. The Praktica series remained in production until the late 1990s eventually adopting most modern features like electronic shutters and auto exposure.

Today, the Praktina FX is generally well known to collectors because of it’s historical significance as the first professional system camera with modern ergonomics. It is a very attractive looking camera that shares a lot of design similarities to the Zeiss Contax F and Pentacon SLRs.

In a post on the Vintage Camera Collectors group on Facebook, I mentioned that I was working on a review of this camera, and several people told me that most of the info out there about this camera is just the same specifications repeated over and over again with little depth. I wondered if perhaps too many people confuse this camera with the Praktica, because of the similar sounding names. The Contax D and Pentacon SLRs are highly desirable by collectors and can often go for some pretty high prices, but the Praktina, which on paper is a much better camera, doesn’t get nearly as much love.

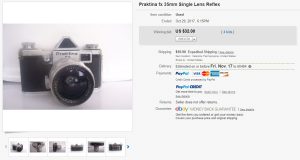

I can’t really say with any level of certainty how valuable these cameras are today. A quick search of completed auctions on eBay partially confirms my suspicion because eBay auto-corrected my spelling of “Praktina” to “Praktica”. I had to put my search term in quotation marks for it to actually accept my Praktina search and when I did, the prices were all over the place, with body only cameras selling for as little as $13 and as high as $60. The image to the right is an incredible bargain of not only a nice looking Praktina, but also with a relatively uncommon Zeiss Flektogon for the low price of $32.

My Thoughts

I mention in the section above how the Praktina has a close resemblance to the Zeiss Contax D and Pentacon cameras, and it was this similarity that led me to this Praktina in the first place. I had acquired a Pentacon FM SLR body and although I had many M42 screw mount lenses to use with it, I was looking for a period correct Zeiss lens that I could pair with the camera. I ended up finding my lens in the basement of Chicago’s Central Camera, but that’s a different story.

Prior to finding that lens, I had been browsing online looking for Zeiss Tessar or Biotar lenses that I could purchase, but the asking prices for the lenses I found were quite high, so I had the genius idea to search for other cameras that might have the lens I was looking for and buy the whole camera. As illogical as that sounds, I have found many cases where a lens can be acquired for less money if its attached to a broken or otherwise undesirable body, than if the lens was sold by itself.

It was during this search that I came across this Praktina with what I thought was the lens I was looking for. I did a bit of research and discovered that although the lens was right, I realized that the Praktina doesn’t use the M42 mount of the Pentacon, so the lens wouldn’t be usable. Still, the camera looked to be in really nice shape and the price was right, so I said what the hell and picked it up.

The seller was selling it for parts because the shutter wouldn’t fire, which likely was why it was so cheap, but upon it’s arrival, I quickly learned that there was an exposed roll of film in the camera that had reached the end, which was likely why the seller couldn’t get the camera to wind or fire. I removed the film and voila! The camera sprang to life! Not only was the shutter working, but the camera looked to be in very nice condition as well! Score!

I had read about some negativity online regarding the quality control of the Praktina saying that it wasn’t as reliable as other SLRs of the era, and based solely on handling it, I quickly disagreed with these comments. The camera felt very solid with a reassuring heft and while test firing the shutter, it made all the right sounds. The body covering is genuine leather and has a texture that’s gripper than the synthetic leatherette or vulcanite coverings on many other cameras of the day. Looking through the viewfinder wasn’t quite as nice as the Pentacon FM in my collection, but only because the Praktina lacks a split image focus aide. The focus screen is changeable on this camera, so had I had access to one with a split image aide, I could have swapped it out. Beyond that, I found the user interface of the two cameras to be quite similar. Both are knob wind and require a bit of extra force because you are not only advancing the film and cocking the shutter, but you’re also lowering the mirror so that light may pass through to the viewfinder.

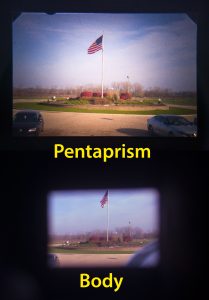

The body’s optical viewfinder is neat, but I found it to be rather unhelpful. For one, its quite small, but it also doesn’t accurately reflect a 50mm image. I don’t have any actual information about what focal length the viewfinder represents, but its definitely more of a narrow angle view, somewhere around the 70 – 75mm range as quite a bit of the visual information was cropped compared to peering through the pentaprism finder. Take a look at the image to the right where I stood in the exact same location and captured an image through both viewfinders. I get why the designers of this camera thought it would be useful to include an alternate to the top mounted finder, but this feature’s quick disappearance in SLR design suggests it wasn’t used very much.

Loading film into the camera is pretty straightforward. Just remember the entire back comes off the camera after releasing the sliding lock on the camera’s left side. Film loads from left to right into the single slotted non-removable takeup spool. Comparing the Praktina to the Nikon F from 1959 which also has a removable back, the bottom of the Praktina stays attached to the camera, which I prefer. I understand Nippon Kogaku based their new SLR after their Nikon S series rangefinder, which itself was designed to compete with the Leica M3, but I think KW really got it right here as there really is no reason to remove the bottom of the camera to install film. Plus, you have the added benefit of being able to set the camera down on a table with the back removed, without it toppling over.

The top plate of the camera is surprisingly modern, with the only notable absence being a rapid wind lever. On the left is the rewind knob with a film reminder dial beneath it. To the right of it are the faded remains of a silkscreened “Germany East” stamp. Apparently, this text changed on various export models with some saying “Germany USSR Occupied” or simply, “Germany USSR”.

In the middle is the pentaprism viewfinder which can be swapped out with a variety of accessory viewfinders. The viewfinder and viewing screen are two separate pieces, unlike the Exakta which has the viewing screen as part of the viewfinder. This is useful as the camera can be used at waist level with the viewfinder removed. I wonder if this design element was something Nippon Kogaku took for their Nikon F.

Removing the viewfinder is not immediately obvious as there is no release on the top or back of the camera where you might expect it. Instead, there is a release latch on the bottom of the camera right in front of the lens mount. In the image to the left, the release is near the bottom of the image and has a “Z” (Zurück) to indicate closed, and “A” (Auf) for when it is open. If you take off the screen, make sure you return this lever back to the “Z” position to lock it into place or it may fall off.

Finally, on the right side of the top plate is the combined wind knob, exposure counter, and shutter speed dial which the user’s manual calls the “Concentrol” system. The shutter speed dial is notable as being one of the very first 35mm cameras with a single dial for both slow and fast speeds. Many cameras, including the previously mentioned Pentacon FM, require a separate switch to toggle the fast and slow speeds. Many other cameras like early screw mount Leicas have a completely separate slow speed dial on the front of the camera. On the Praktina, the dial rotates freely from 1 second all the way to 1/1000. You can change speeds whether the shutter is cocked or not, and you can turn it clockwise or counter clockwise. There’s even a marking for a 1/75 shutter speed! Neat!

The bottom of the camera is fairly spartan, covered mostly in black leather. There’s the center mounted tripod mount and rewind button, and that motor mount which is one of the most innovative features of the Praktina. Both an electronic automatic winder, and a spring loaded winder were available. In my research for this article, I’ve seen more images of the spring loaded winder so I have to image it was more popular (and probably cheaper). If you are interested in seeing the spring loaded winder (and a really cool lens) in action, check out this Youtube video.

The body of the Praktina has lugs for a strap if you so choose to use one, and twin flash sync ports, one for flashbulbs and one for electronic flashes. The M-sync port is synchronized at all speeds, and the X-sync is synchronized only at 1/25 and 1/50. Finally, there is a 10-second mechanical self timer which can be used to delay the shutter release.

In use, the Praktina works much like a modern SLR, at least modern in the sense of a camera designed 1-2 decades later. The only real reminder that you’re using an old German camera is in the positioning of the front mounted shutter release and the knob wind for film advance. The lack of a split image focus aide did not impact my ability to focus the camera as the viewfinder is surprisingly bright considering I’m using a Zeiss Tessar with a maximum aperture of f/2.8. A good number of Praktinas were sold with a Zeiss Biotar f/2 or a Steinheil Quinon f/1.9 lens which would have improved open aperture viewing by a full stop.

A word about the particular Zeiss Tessar lens mounted to this camera. This lens supports full open aperture viewing, but it’s not automatic. This is still a preset lens in that you must set the lens to your chosen aperture first, and then in a separate step, open the aperture all the way via a sliding lever on the bottom of the lens. In one of the images above where I show the lock for the viewfinder on the bottom of the lens mount, you can see this unlabeled slider on the lens itself. This lever is spring loaded and will reset each time you fire the shutter. If you don’t remember to reset this lever after each exposure, the camera can still be used, but the aperture will stop down to whatever you have selected, making the viewfinder darker.

Another useful feature of this Zeiss Tessar lens is that it has a minimum focus distance of 1.65 feet, which allows for some really cool closeups. Not quite macro, but a lot closer than the minimum focus distance of 3 feet that many cameras often had. As this was the only lens available to me on the Praktina, I am not sure if other lenses could get so close.

My Results

My excitement continued to grow throughout my ownership of this camera. It started out as a curious cheap pickup of a camera that was in questionable working condition and one that I assumed wouldn’t be much different from another in my collection, to one whose differences continued to reveal itself upon handling of the camera and one whose quality seemed to be second to none.

I was very excited by the time a chance to shoot this camera came around in the summer of 2017 and I loaded in a 36 exposure roll of Fuji 200 into it. I played with the camera prior to loading film enough to feel pretty confident in it’s condition and in my ability to shoot it.

As it turned out, the camera’s shutter wasn’t in as good of shape as I had hoped. While it fired on each and every one of the 36 shots and the exposures came out pretty good, there are obvious light leaks both from the curtain not completely shutting after firing, and pinhole light leaks that I missed when I vetted the camera.

Oddly, the light leaks ranged from severe to nearly invisible throughout the roll. It seemed that there is some kind of tension issue on the second curtain causing it to not close all the way in some of the shots. You can see this clearly in the last two shots in the gallery above. In the world of “happy accidents”, neither image was ruined and the white leaks gave the image a sort of “frame” effect that a more artistic person might have intentionally applied in post. Rest assured, that these leaks are straight out of the camera and the only post-processing done to any of these images are very subtle contrast adjustments.

Despite the leaks, there was enough good here to make a pretty good judgement that in good working condition, the Praktina is one hell of a camera. I mentioned earlier in this review that this model has sort of a reputation as an unreliable camera, and the issues above don’t disspell that, but in the camera’s defense, this is a 60+ year old camera with cloth curtains. It is not reasonable to expect any shutter to last this long without some issue. Even the most sought after Leicas and Exaktas require service after the same length of time, so I can absolutely say that any of the issues in the photographs above should not be considered “faults” of the design of the camera.

I had fun using the Praktina without the pentaprism. Like most other SLRs with interchangeable viewfinders, the camera can be used at waist level like a TLR or box camera with the viewfinder removed. This allows you to get the camera much lower to the ground which can be useful when capturing images of children, pets, or pretty much anything else at a low angle. My shots of the stone statue and the little boy in the gallery above were done with the prism removed.

The Praktina is an awesome camera, and despite the light leaks, I loved the images I got from it. I’ll even go as far as to say that the build quality and attention to detail applied by the engineers at KW when this camera was designed, produced one of the best classic 35mm cameras of all time. I thoroughly enjoyed using this camera, much more than I had anticipated, and if I were so inclined to have it professionally repaired, I absolutely believe this would become a staple of my collection and a camera that I would use again.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The KW Praktina was an extremely well built and innovative camera, designed for the professional photographer at a time where options for high end 35mm cameras were limited to only the Exakta. Despite it’s age, the Praktina shoots much like a modern camera. I think the camera is very handsome sitting on a shelf, but is also a joy to use. As with any 60+ year old camera, condition issues, especially with the shutter are common, but that’s not due to any fault in the construction of the camera. In good working condition, it is very easy to get excellent images from the Praktina, and with the huge variety of accessories available for it, this is a collector’s dream. I am extremely happy this camera is in my collection and I loved the results I got from it. I didn’t think the review would end this way, but using the scale below, the Praktina FX gets one of the highest scores I’ve ever given to a camera. Highly recommended! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.3 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Praktina

http://www.praktina.com/pqcam06.htm

http://www.praktica-collector.de/Praktina.htm

http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/entry_C620.html

http://randomphoto.blogspot.com/2015/05/kws-praktina-fx.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/praktina-fx-fx-a-version-c.408677/

Very interesting article. I discovered Praktica Ltl and Ltl 3. You got me interested in buying Praktina cameras as well. Thanks for all the info! Greetings from Sweden.

The Praktina FX was the first “precision” camera I ever bought, back in about 1969-70! I got some pretty good pictures from it, before I had to drink the Japanese “coolaid” and get into the systems my bosses had at the studios where I worked. I have to say, there are features about this camera, and the Praktica Super TL I owned, that I would still use on a “super-camera” if I were designing it today! Especially the angled shutter release on the body in front, talk about stability!

I re-bought two Praktina FX about 10 years ago, and I actually found an old-timer to clean lube and adjust the old-style “semi-auto” lens that came with it; but since Essex camera went out of business, I haven’t found anyone to work on the bodies!

Thanks for sharing your story Andy! I have found some step by step instructions online for adjusting and replacing the shutter curtains on the Praktina, but it’s well beyond my skill level! There aren’t many old cameras I would one day consider paying someone to service, but this is one!

Don’t forget a nice Praktina T-shirt! I actually bought one of these a few years ago!

http://axistshirts.com/detail/praktina_tan

Mike, I thought of this article this morning. I got very lucky and found a Carl Zeiss Biotar 5,8cm f/2 T Praktina mount at the Sydney Camera Market and the seller obviously did not know what it was. I picked it up for $2. Now to find a camera to attach it to! Thanks for this article, gives me heaps of information needed.

I got Praktina few months ago on a flee market, sadly it has shutter issues the same like my Contax F.

Very nice article.

Shyrokov, glad to hear you find yourself a Praktina, but sadly, shutter issues on them are common. Mine doesnt even work 100%, as I had to limp it along to finish a roll. The only real way to get one of those in perfect working condition is to have it professionally serviced. I am sure you could find someone to do it, but the question will be, how much will it cost?! 🙂

Hello Mike,

Where did you found step by step instructions for replacing the shutter curtains on a praktina? I am looking for that.

Best regards, Matthias

You can get these serviced and repaired at Photo Service Olbrich, who are located in Gorlitz, Germany. For about 150 euros they will replace the shutter with a new one and do a full CLA.

Proud owner of an old FX. I just wanted to thank you for explaining the amazing backstory of the company and the Nobles. Unbelievable.. They could turn this story into a movie.