This is a Robot Junior (sometimes incorrectly called the Star Junior or Junior Star) made by the Robot Berning Company in Düsseldorf, Germany starting in 1954. The Junior was an economy version of the Robot Star released two years earlier which lacked a 90 degree right angle viewfinder, and rewind mechanism, but was otherwise the same. The Robot Junior, like most Robot cameras took 24mm x 24mm square exposures on standard 35mm film. The reason for this was partially due to the size of the camera’s unique rotary shutter, but also to keep the camera as compact as possible. Featuring an interchangeable lens mount and a clockwork motorized film advance capable of up to 4 frames per second, the Robot Junior is truly a unique and fascinating camera.

Film Type: 135 (35mm) (24mm x 24mm square exposures)

Lens: 38mm f/3.5 Schneider Kreuznach Radionar coated 3-elements

Lens Mount: 26mm “Robot” Screw Mount

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus

Shutter: Rotary

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 627 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/robot_junior_star.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Berning Robot Junior is a high quality compact camera that shoots square 24mm exposures on regular 35mm film. Although it requires a special take-up spool unique to these cameras, it accepts normal 35mm cassettes on the supply side. In addition to it’s unique exposures, it also has a wind-up clockwork motor that allows for automatic film advance and setting of the shutter after each exposure, and has an interchangeable lens mount. It’s feature set and exposure size, excellent build quality, compact size, and outstanding optics made this one of the most unique and fun to use vintage cameras ever. I highly recommend this model to anyone who is interested in old film cameras. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for pioneering design, unique feature set, and all around wow factor | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.7 | ||||||

History

Note: Almost all of the information below comes from the excellent German language website, http://www.robot-camera.de. Google Translate wouldn’t work correctly on this site, so I had to copy and paste nearly everything manually, and some of the translations were very poor. What follows is my best attempt at not only interpreting the German to English translation, but also paraphrasing the article without retyping it word for word. If I get something wrong, please let me know!

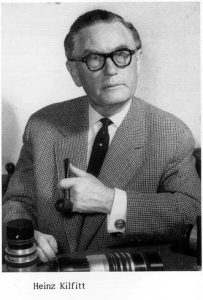

The story of the Robot camera starts with a man named Heinrich Wilhelm Kilfitt. Born on May 29, 1899, Kilfitt was the son of a watchmaker and worked in his father’s shop repairing watches and other clockwork devices. As a young adult, he took an interest in photography and in 1926, sought to combine his knowledge and experience in watchmaking by creating an all new clockwork compact camera.

When it was completed in 1931, Kilfitt’s prototype had a unique spring wound clockwork motor that both controlled the film advance and the setting of the shutter for rapid sequence shots. It was a compact and lightweight camera that used double perforated 35mm cinema film (standard “type 135” 35mm film would not be introduced until 1934) that took 24mm x 24mm square exposures in specialized film cassettes.

Kilfitt shopped around his new prototype to various camera and optics companies of the time including AGFA, Kodak, and others, but none of these companies saw the potential for such a small and unique camera.

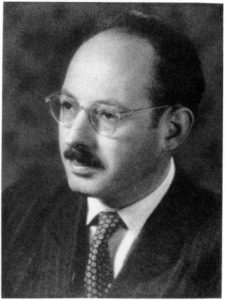

A year later in 1932, Kilfitt showed his prototype to a young man named Hans-Heinrich Berning whom he had met in private school in the 1920s. Berning was the son of Otto Berning, who owned a successful clothing company in the 1920s and 30s. The younger Berning was fascinated by the design of Kilfitt’s new camera and showed it to his dad who agreed to help finance production of the camera.

With financial help and guidance from his father and uncle Hermann Berning, Hans-Heinrich Berning and Heinrich Kilfitt setup a design office in Düsseldorf to start production of the camera. The as of yet unnamed company would hire a mechanic named Franz Hörth to assist in the production.

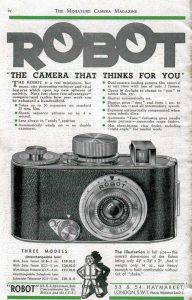

In 1933, the new company was officially christened Otto Berning & Co., and a year later production was up and running for the camera which was given the name “Robot” with the tagline “The camera that thinks for you”. The complex design of the Robot meant that not every piece of the camera could be built by the small company, so they needed to outsource some parts. The rotating shutter assembly was built by Alfred Gauthier GmbH (maker of Prontor and Vario shutters), another watchmaker named Baeuerle & Sons created the specialized springs needed to tension the shutter, and the light weight alloy metal used in the body was created by a company called WMF of Geislingen.

The first Robot, known today as the Robot I, was available for sale in 1934, but early production was slow. At the 1935 Leipzig Spring Fair, orders for the Robot camera far exceeded production capacity, so waiting lists were often quite long. Over the next few years, the Robot camera became a huge success, and in 1937 would win the Grand Prix award for design excellence at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair.

Although selling well, the Robot I had a temperamental shutter, a primitive viewfinder, and no ability for flash synchronization, so in 1937 Heinrich Kilfitt began work on a new model which would eventually become the Robot II. Released in 1939, the Robot II was a huge upgrade to the original model. Featuring an entirely new body with a larger and integrated viewfinder, a larger and more robust spring wound mechanism, and an improved shutter that added support for faster lenses by Zeiss and Schneider. The camera also added flash synchronization and changed the style of film cassettes needed to improve compatibility with modern “Eastman Kodak 35mm film”.

Strangely, after the release of the Robot II in 1939, Heinrich Kilfitt would leave Berning and form his own company where he would continue on in the optics industry making lenses and cameras. Some sources online suggest he was responsible for the Zoomar lens which was the first successful still camera lens with an adjustable focal length. He also is said to have created a strange 35mm SLR that shot 24mm x 24mm square images called the Mecaflex in the 1950s.

Around the same time as Kilfitt’s departure, the Otto Berning company would be renamed to Robot Berning & Co, to align the company with it’s main product. The Robot II would remain in production during World War II and became popular among both the German Luftwaffe and Allied air forces due to it’s compact size, rapid fire shutter, and availability of high quality lenses.

After the war, due to damage sustained by Allied bombers and a loss of parts inventory, it took a while for Berning to resume operations at the main company headquarters in Düsseldorf. By 1948, production would resume of the Robot II which at the time was identical to the pre-war models.

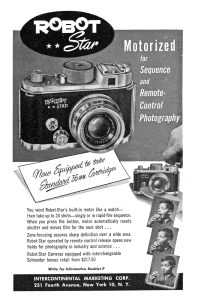

In the early to mid 1950s, the Robot Berning Company was very successful with demand far outpacing the company’s ability to build cameras which caused many Robot cameras of this time to sell for inflated prices. In 1951, the Robot II would be revised to accept modern Eastman 35mm cassettes without any special loading steps. In 1952, a model called the Robot Star would be released adding the ability to rewind the film back into the 35mm cassette at the end of the roll, and a unique 90 degree viewfinder allowing the photographer to look in the side of the camera for “discreet” photography. Although very popular, Robot cameras were not cheap. The ad to the right for the Robot Star has a list price of $217.50, which when adjusted for inflation is over $2000 today!

The model being reviewed here, the Robot Junior, was released in 1954 and was a less expensive version of the Robot Star, losing that model’s rewind knob and the 90 degree viewfinder.

The Robot Berning Company would eventually release a rangefinder model called the Robot Royal III that had a unique body with coupled viewfinder, and one called the Robot Royal 36 that captured standard 24mm x 36mm sized images on regular 35mm film.

Robot cameras would continue to evolve and be produced over the next couple of decades, but largely in specialized applications, such as aerial cameras, traffic cameras, or as commercial security cameras. In my research for this article, I found a model called the Robot SC Electronic from the early 1980s that appeared to be used in commercial applications with an external power supply.

In 1999, the Robot Berning Company would be acquired by Jenoptik, a Jena, Germany based optics company that has a long history with the Carl Zeiss Foundation, who continues to manufacture all sorts of optical products such as digital microscopes, infra-red cameras, and photo diodes.

Today, Robot cameras are highly desirable by collectors and users alike due to their excellent build quality and unique feature set. There were very few cameras designed in the 20th century that used the 24mm square format, and none that also had a clockwork motorized film advance. The combination of a unique design, great looks, reliability, and excellent optics make all Robot cameras a prized possession for any collector.

The Robot Junior was originally sold in large numbers, and this combined with it’s economy feature set make it slightly more affordable today than other Robot models. Sold prices on eBay fluctuate wildly from as little as $75 to above $200 in perfect working condition. If you ever have an opportunity to pick up, or even try out a Robot camera, I encourage you to do so.

My Thoughts

When collecting film cameras, the greatest appeal for me are in the cameras that offer a unique shooting experience. The more quirky a camera, the more interesting it becomes to me. If my only interest in film photography was making good looking 24mm x 36mm negatives on 35mm film, I’d get a Nikon F6 and a couple lenses and stop there.

The idea of shooting something that’s different from the norm appeals to me, so that’s why I have always had an interest in half frame, or less common square frame cameras. The Univex Mercury was an early favorite of mine for a variety of reasons, but since then I’ve acquired a variety of other half frame cameras like the Olympus Pen, Fujica Drive, and Agat 18K. Square frame cameras are quite a bit less common, so as of this writing, the only one I’ve had the pleasure to shoot was a Photavit IV.

In addition to irregular sized images, another feature of mid-century cameras I’ve become enamored with are clockwork “motor wind” cameras in which a spring tensioned knob is wound up to quickly advance the film transport and set the shutter in advance of the next shot. These early mechanical wind cameras allowed for what was at the time, lighting fast shots that when used properly could fire the shutter faster than once per second. This was great for action photography in which a photographer could capture multiple exposures in quick succession without having to mess with an advance lever (or knob).

In the 1950s and early 60s, there were a huge number of cameras with this feature. Models like the Kodak Motormatic 35, Fujica Drive, GOMZ Leningrad, and others had a large knob somewhere on the body that would allow you to wind up the camera and have it ready for 8 or more quick shots.

Of all these motor wind cameras, the Berning Robot series was the most famous and probably the most successful. The first model was released in the mid 1930s and the company kept making them at least until the 1960s. These cameras are quite rare and usually expensive, but when I had the opportunity to borrow one from fellow collector Mark Faulkner, I gladly jumped at the opportunity.

The Robot Junior is a gem that fulfills two of my desires for interesting or quirky cameras. It is both a clockwork motor wind camera and it shoots 24mm square images on regular 35mm film. Like the Photavit that shoots the same size exposures, the Robot has a proprietary take up spool that must be included in the camera or else you won’t be able to advance the film, but unlike the Photavit, a standard 35mm cassette will fit on the supply side, eliminating any special steps needed to load the camera. It did not take long after the Robot arrived in my mailbox that I loaded up some film and went shooting.

Looking down at the top of the camera we have the accessory shoe on top of the viewfinder. One of the two differences between the Robot Junior and the Robot Star that it is based upon, is the lack of any way to rewind the film back into the cassette after you complete a roll. This area of the camera is where that knob would be.

Next to the shoe, centered on top is the large wind knob. The tension on the knob is quite high, so you’ll need to use a bit of strength to wind it up. On this example with a full wind, I was able to get between 16-18 exposures before it needed to be wound again. There are some Robots with a taller knob which allows you to get even more exposures before having to wind the camera again.

Next to the large knob is the shutter release button which is threaded for a cable release. Since a loaded camera is always ready for the next exposure, there is a sliding lock beneath the shutter release that should be engaged when the camera is not in use to prevent accidental exposures. Finally, there is the exposure counter and reset knob. The exposure counter needs to be manually set each time film is loaded into the camera and can count as high as 54 exposures.

The back of the camera features a Robot logo near the bottom of the door, and a small circular eyepiece for the viewfinder. The Robot is a scale focus camera, so without the need for any type of rangefinder, the view through the viewfinder is just a square window. It is small, but works well enough for the standard 38mm lens (50mm equivalent). If you were to use a lens with any other focal length, an accessory viewfinder would need to be attached to the camera.

To open the camera, you must slide a lock on the camera’s right side to the open position. The door is hinged on the right, revealing a small film compartment.

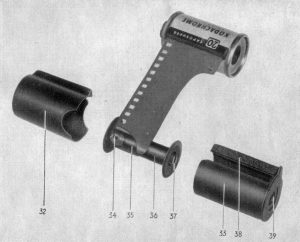

Compared to the Photavit, the film compartment in the Robot Junior is large and roomy. A normal 35mm cassette fits on the supply side on the left. On the right however, is a proprietary Robot type “N” film cassette.

The Robot cassette is spring tensioned in a way that it will automatically close, sealing off light form entering when out of the camera. When inserted into the camera and the door shut, a chrome bar on the door presses on the cassette in a way to relieve tension on the spring, allowing film to freely travel into the cassette.

To properly load the Robot cassette, you must break it down into three pieces. Two outer shells, and an inner spool. The image to the right from the Robot’s user manual shows how this is done. Simply attach the leader to the spool and reassemble the cassette in the opposite of how you took it apart. Pay attention to the bottom of the cassette when inserting it back into the camera as there are two metal stubs that must be in a specific orientation to properly load the cassette.

With the camera loaded with film, you must advance it a couple of times to get past the exposed leader. The film gate on the Robot is smaller than a typical 35mm camera, so you should be able to easily get a few exposures on the ‘0’ and ’00’ position on a modern roll of 35mm film.

With the camera loaded and ready to go, you’ll need to manually set your chosen f/stop and shutter speed as this is a fully manual meterless camera. You could optionally use some type of handheld meter, or shoot Sunny 16 to calculate the correct settings. The shutter speed dial is on the front of the camera near the 8 o’clock position of the lens. Engraved on the outer edge of the dial are 8 speeds from 1/2 to 1/500 seconds plus Bulb. 1/2 through 1/50 are indicated in red and the rest in black which correspond to the two flash sync ports next to it. Red speeds are suitable for M-sync (flashbulb), and black speeds for X-sync (electronic flash).

Around the perimeter of the lens are controls for focus (in meters) and the f/stops of the lens. The example being reviewed here has a Schneider Radionar f/3.5 lens, but lenses as fast as f/1.9 were available for the Robot.

If you have other lenses, changing them is just as easy as any other screw mount camera. Simply grip the lens and rotate it counter clockwise to remove and clockwise to put a new one back on.

The Robot Junior lacks two features that were available on the Robot Star, which is the 90 degree viewfinder and the ability to rewind the film. Although I did not have access to either of these features, I think the 90 degree viewfinder was more of a gimmick and not really useful for what I would be using it for, but the ability to rewind would have been nice. Without it though, unloading the camera only required that I cut off the tail of the film in the dark and load it onto my reel for developing. If you use a lab to develop your film, you’ll likely want to open the camera in darkness, remove both the 35mm cassette and the Robot cassette and rewind the film by hand so that you may send in the 35mm cassette for developing. You could also just send the Robot cassette in, but you’ll want to make absolute sure that your lab will return it to you as original Robot cassettes are not easy to come by.

All Robots are neat cameras, and the Robot Junior did not disappoint. Even without picking it up, the camera just looks cool. The colorful Robot Junior logo is attractive and gives a splash of color to what is normally a rather drab silver and black theme on most cameras. The build quality of this thing is excellent and although compact, has a bit of heft, suggesting a well built camera. It may require a couple extra steps to load and unload, and there is no meter, or any kind of automatic exposure, but that’s not really the point with a camera like this. It’s unique combination of a clockwork motorized film advance, and square images means there are very few cameras like it.

My Results

For my first roll through the Robot, I chose a 12 exposure roll of expired Polaroid color 200 film. Despite being expired, I’ve used this film before and know that it shoots pretty true to box speed and gives good results. There isn’t a lot of information about people adapting modern film to Robot cameras, so I wasn’t sure if I would run into fitment problems with a 24 exposure roll in the Robot cassette. I figured with the 24mm wide exposures, I should get somewhere around 18 square exposures on the 12 exposure roll.

I reset the frame counter on the camera to 0 and expected to feel resistance from the end of the roll of film around the 18th exposure. When I got there, the camera kept firing, 19, 20, 21, and then after the 22nd exposure, I noticed the camera stopped advancing. Did I really get 22 exposures on a 12 exposure roll of film?

Yep! Upon developing the film myself using the Film Photography Projects C41 Unicolor kit, I was elated to see 22 properly spaced exposures on the roll of film. I mentioned earlier in this review that the short distance across the film plane of this camera means you can get more exposures on the leader (0 and 00 positions) of most rolls of film, plus an extra one or two after what would have normally been the 12th exposure. This phenomenon is how companies like Bolsey were able to promote an extra frame or two on the Bolsey B2 with it’s short film gate distance.

As I expected, the results came out properly exposed, and with good detail. The expired nature of the Polaroid 200 film added a slight color shift, but nothing too extreme. I was in love with the square 24mm images so much that while scanning them, I had to keep reminding myself these weren’t 6×6 medium format scans. They certainly don’t have the resolution of a Rolleiflex, but with an exposed area that’s 16% the size of a 6cm x 6cm (576 sq mm vs 3600 sq mm) you can’t possibly expect that level of detail.

I love everything about this camera. The way it looks, how it feels in your hand, the experience shooting it, the sound of the clockwork motor, and the images it makes. Had this been the Robot Star with the rewind capability, it would have been perfect, but even that small omission is minor for someone who is used to loading and unloading cameras in the dark.

There are certainly more feature rich cameras, or those with better lenses, or worth more to collectors, but the Robot Junior is the perfect combination of what I love about shooting old cameras. It’s different, it’s fun, and it makes great images! What more can you ask for? This is absolutely one of my favorite cameras I’ve ever shot, and I hope to be able to add another to my collection some day.

Additional Resources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robot_(camera)#Robot_Star

http://www.robot-camera.de/ROBOT_Kameras/Robot_Junior/robot_junior.html

Fascinating review Mike. As you say, the Robot cameras are very collectible and your write-up clearly shows why. The clockwork winding is a spectacular feature!