Ernie Kaltenbrunner: Why do you eat people?

1/2 Woman Corpse: Not people. Brains.

Ernie Kaltenbrunner: Brains only?

1/2 Woman Corpse: Yes.

Ernie Kaltenbrunner: Why?

1/2 Woman Corpse: The PAIN!

Ernie Kaltenbrunner: What about the pain?

1/2 Woman Corpse: The pain of being DEAD!

Ernie Kaltenbrunner: It hurts… to be dead.

1/2 Woman Corpse: I can feel myself rot.

Ernie Kaltenbrunner: Eating brains… How does that make you feel?

1/2 Woman Corpse: It makes the pain, go away!

My first two editions of the Cameras of the Dead series were an homage to two “Living Dead” classics, George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, and it’s sequel, the Dawn of the Dead. Both movies are considered by many to be two of the most influential zombie movies ever made. They are staples of any fan of the horror genre and despite their low budgets and primitive make up effects, still stand up today as truly terrifying movies.

For my third edition, I am jumping trilogies and moving to another zombie classic, 1985’s Return of the Living Dead. Although not done in Romero’s style, in my opinion, this movie inspired modern zombie movies in ways the originals never did. Where Romero’s movies consistently had a quasi-political theme rife with social commentary, the Return of the Living Dead movies just took the zombie concept and had fun with it, LOTS of fun!

For my third edition, I am jumping trilogies and moving to another zombie classic, 1985’s Return of the Living Dead. Although not done in Romero’s style, in my opinion, this movie inspired modern zombie movies in ways the originals never did. Where Romero’s movies consistently had a quasi-political theme rife with social commentary, the Return of the Living Dead movies just took the zombie concept and had fun with it, LOTS of fun!

While it’s pointless to compare “Return” to any Romero movie, I love it just as much, and it has no less than three of my all time favorite scenes in any horror movie ever. There is the infamous dialogue quoted above with a half-dead zombie corpse who explains why zombies need to eat brrraaaiiinnssss, to the awfully fantastic fight sequence with Tarman at the end of the movie, and then the completely out of place scene in which a punk rock girl named Trash strips naked in a cemetery and starts gyrating in front of the camera. Why is this scene even in the movie? I don’t know, but 13 year olds everywhere in the 1980s loved watching it late at night with their buddies in their parent’s basement on Skine-max!

Since the make up effects in the 1980s allowed for extra gore in the zombie genre, I am going to up my game here in my Cameras of the Dead series and show you some real nasty cameras!

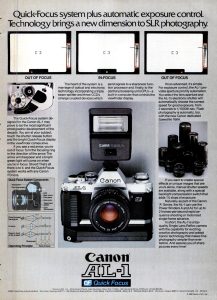

Canon AL-1 (1982)

This is a Canon AL-1 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera which was first introduced in March 1982. It was the last in the Canon A-series which started with the AE-1 in 1976, and was one of Canon’s last cameras to use their aging FD lens mount. The AL-1’s signature feature was a very innovative focus confirmation system which allowed photographers to use manual focus lenses and see LED indicators in the viewfinder that would help them get perfect focus. Although the AL-1 was not a true auto focus camera, it served as a bridge between existing manual focus only cameras, and a true autofocus SLR. Combined with aperture priority auto exposure, the AL-1 was a pretty advanced camera that simplified exposure and focus composition for novice photographers.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens Mount: Canon FD Breech / Bayonet Mount

Lenses: 50mm f/1.8 + others

Focus: Fixed SLR Prism

Shutter: Focal Plane Cloth

Speeds (Auto): 2 – 1/1000 seconds stepless

Speeds (Manual): B, 1/15 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: TTL Center Weighted Silicon Photo Cell with Aperture Priority Auto Exposure

Battery: 2 x 1.5v AAA Batteries

Flash Mount: Hotshoe and PC MX Sync

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/canon_pdf/canon_al-1.pdf

My Thoughts

The Canon A-series remains one of the most popular and successful lineups of cameras ever made. Millions of AE-1s were sold in the 10+ years they were made, and many of them are still used widely today. Despite the success of the AE-1, I never found myself drawn to them and despite owning at least 4 of them over the years, I never enjoyed them enough to keep one, and as a result, I’ve resold every one that has come my way.

There are two primary reasons I am not a fan of the AE-1. The first is that the camera requires power to work. It is a completely electronic camera that doesn’t do anything if the battery dies. While that’s not exactly unique to the AE-1 as there have been many other SLRs that suffer the same fate with a dead battery, it doesn’t have to be this way. All Nikon SLRs made during the production run of the AE-1 are still usable with at least one speed, with a dead battery, even the lowly Nikon EM. This means that the AE-1 consistently is lower on my list of cameras to grab when I want to shoot an old SLR.

My second complaint with the AE-1 is that it’s auto exposure system is shutter priority. While there are some advantages to shutter priority like when shooting sports or other fast moving objects, and I can certainly understand that for a beginner trying to explain shutter speeds is a lot easier than aperture f-stops, I find that in my style of photography, I prefer aperture priority much more.

While I acknowledge that the AE-1 was a generally good camera that had a large selection of excellent Canon FD mount lenses, I have never found myself drawn to it, or any Canon A-series for that matter. Then I discovered the Canon AV-1.

The Canon AV-1 is a simplified version of the AE-1 that is also completely electronic, but it supports aperture priority auto exposure. Although it lacks any sort of full manual control, the AV-1 is physically smaller and weighs less, and has a better designed battery compartment than the AE-1, yet it supports all the same lenses. The Canon AV-1 was one of the earlier cameras I reviewed on this site, and since that post was first published back in May 2015, I’ve taken it out numerous times since then. I find the compact and lightweight feel of the body, with the bright viewfinder, and awesome Canon lenses to be an excellent combination. If I want a mechanical, fully manual camera, I just take something else, but for those family trips to the zoo where I don’t want to think, the AV-1 is a great choice.

Then one day, I learned of yet another Canon SLR with aperture priority auto exposure, but it also had a unique focus assist feature. It even offered more manual speeds than the AV-1’s single 1/60 manual speed. I thought, WOW, this could be the perfect Canon SLR! I could still use my Canon FD mount lenses, and would still have aperture priority auto exposure, but the camera could also help me judge accurate focus, just like my Nikon D7000 DSLR does when I use manual focus lenses! I was sold, until I started to look for one.

The Canon AL-1 isn’t an auto focus camera in the traditional sense. It is still a manual focus camera, but it uses an array of three sensors that act as sort of an electronic rangefinder to determine whether something is correctly in focus or not. Canon called this the “QF” or “Quick Focus” system. The QF system was advanced for it’s day and worked quite well. Although I have not found any evidence of this, I would guess that the research and development needed while making the AL-1 meant that the camera was sold as a loss. I have to imagine that Canon used this model as a test platform while developing their eventual auto focus EOS platform which would debut with the EOS 650 in 1987.

The Photography in Malaysia “MIR” site has an excellent write up of how the Quick Focus system worked in the AL-1. I won’t duplicate too much here, but if you are interested, I highly recommend reading their article. The gist is that by having a reflex mirror with an intricate semi-transparent pattern, some of the light from the lens would pass through the main reflex mirror and be reflected onto a second “sub-mirror” that pointed to 3 CCD line sensors on the bottom of the mirror box. You can see both the semi-transparent pattern, and the sub-mirror (inset) in the image to the right.

These sensors would measure whether or not the image passing through the lens was in focus or not. Using 3 LEDs visible in the viewfinder, two left and right arrows would indicate if the image is over or under focused, and a third green dot would indicate proper focus. This type of focus confirmation became standard in the years to come, and a similar system it still used today on fully automatic digital cameras when using manual focus lenses.

This QF system on the AL-1 is reported to have been very accurate and very easy to use. In the early days of auto focus cameras, Canon was always ahead of other companies like Nikon who took a bit longer to perfect their AF systems, so I have no doubt that the QF system in the AL-1 likely worked very well. In fact, in an article from a 1982 issue of Modern Photography, the reviewer was impressed with the accuracy and flexibility of the Quick Focus system, saying:

Canon’s designers have had admirable success in creating a reasonably-priced, simple, and straightforward SLR with electronic focus indication designed to meet the needs of many of today’s SLR users. The AL-1 Quick Focus will not only speed up, but also sharpen up, the focus of users uncomfortable with the subjectivity of focusing.

The entire review is in the gallery below if you are interested in reading a 1982 take on this camera.

It is clear that a lot of effort went into the development and design of the AL-1, but sadly, one other choice proved to be a huge issue which was the battery compartment. By the time the AL-1 was released, more and more cameras were featuring AA and AAA alkaline and manganese batteries. Although these batteries were larger than the button cell ones that came before them, they were much cheaper and lasted quite a bit longer. Plus, by relocating the battery compartment inside of a hand grip, early SLRs like the AL-1 and the Nikon FA showed the first hints at a modern hand grip.

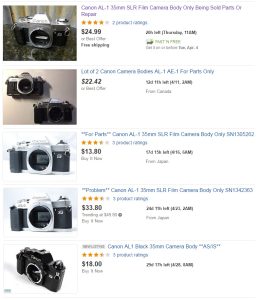

The problem is that for whatever reason, the battery door on almost every AL-1 out there is broken or completely missing. Even for ones that aren’t missing, there is a metal plate that is supposed to be on the under side of the door that completes the circuit between the two batteries. The example being reviewed here was no different and was missing this flap. I had the idea to shove some kind of conductive metal foil to complete the circuit and then tape the batteries into the chamber, but that didn’t work. No matter how much I tried, the electronics of the camera would never respond to any attempts to give it power. Using my tools, I tried to disassemble the bottom plate and battery compartment and possibly clean off some corrosion, but that didn’t work either.

This camera sat in a box for over a year before I recently came back to it, attempting to give it one more shot at working. I was unsuccessful, which is why the camera is being reviewed as a dead camera, instead of a full review. It’s such a shame too, because I feel the AL-1, this could have been a perfect SLR, not just by Canon, but anyone. To my knowledge, only Minolta had a manual focus SLR with a focus confirmation feature, but that model, the X-600, was only sold in Japan in very low quantities and is very rare today. Not Nikon, Pentax, Olympus, or any other company had a similar model that was sold in mass quantities with this combination of features.

I can’t help but be intrigued at the possibilities of how the AL-1 could be used. Sure, you can use manual focus lenses with focus confirmation on any number of modern auto focus cameras by either turning off the AF feature, or by attaching a manual focus lens, but the AL-1 is a bona-fide manual focus camera with automatic focus detection, a wind lever, mechanical rewind, and a lightweight and compact body. As auto focus cameras got more and more advanced, they lost many of these features, and got larger and heavier.

I have searched online for working AL-1s and they do exist, but the price you’ll pay is quite high. I’ve read that if you get the motor drive unit for this camera and attach it to the camera, it holds the battery door shut just enough to keep it working. You could also use some electrical tape to hold the door shut (as many likely have done), but I think if I am ever going to add another AL-1 to my collection, I want one that works how it was supposed to, no motor drive, and no electrical tape required. Until then, the Canon AL-1 is here as a Camera of the Dead.

Kowa SE-T (1965)

This is a Kowa SE-T 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by Kōwa Kōki Seisakusho (Kowa Optical Works in English) around 1965. The SE-T was part of a range of leaf shutter SLR cameras made by Kowa from about 1960 – 1972. Earlier Kowa SLRs like the SE-T had a fixed lens that had a variety of screw in adapters to change the focal length of the built in 50mm lens. Later Kowa SLRs came with a proprietary bayonet lens mount. Kowa SLRs like the SE-T were nicely designed and compact SLRs that came with good lenses and a competitive list of features, but over the years have suffered the same fate as many leaf shutter SLRs which is poor reliability.

Lens: Kowa 50mm f/1.8 6-elements coated

Focus: Fixed SLR Prism

Shutter: Seiko MXV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: TTL CdS Coupled Meter

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: Accessory Cold Shoe and PC MX Sync

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/kowa_se_t.pdf

My Thoughts

This is the second leaf shutter SLR to be featured in the “Cameras of the Dead” series, and I’m starting to think there’s a correlation there. In my review for the Kodak Retina Reflex III, which was another leaf shutter SLR made by Kodak AG, I found that some of the same challenges with that camera applied to the Kowa SE-T. SLR cameras have almost always had a focal plane shutter, usually made of cloth, which functions as a barrier from light hitting the unexposed film loaded into the camera. Leaf shutters on the other hand were very popular in other camera designs over the years, including rangefinders, TLRs, and box cameras since there is no need to have light pass through the shutter until the instant the photo needs to be taken.

While it might seem that using a leaf shutter on an SLR might have been a straightforward swap, it actually was quite complicated. For one, in a focal plane shutter, the reflex mirror which reflects light up into the viewfinder is in front of the shutter. The shutter can remain shut, blocking light from the film plane up until the moment of exposure. On a leaf shutter camera, the shutter is in front of the reflex mirror, which means that in order for light to be reflected up into the viewfinder, both the shutter and aperture iris must remain wide open while composing. Since the shutter is open at all times while composing an image, a separate flap called the “capping plate” must fold down behind the mirror, blocking light from entering the film plane and prematurely exposing the film. The image to the right shows the capping plate in it’s closed position in the film compartment blocking light from hitting the film during composition.

During storage, or when the shutter is not cocked, the shutter remains closed, and the mirror and capping plate remain in the upright position, blocking all light from entering the viewfinder. In order to see through the viewfinder, you must first advance the film using the wind lever on the bottom of the camera.

Then, when the photographer is ready to capture an image, a convoluted series of events must unfold to first close the shutter, then the capping plate and the reflex mirror flip up out of the way, the aperture iris stops down to it’s selected setting, the shutter reopens to expose the film for whatever length shutter speed has been selected, then close again to stop the exposure, all while happening upon the moment the shutter release button is pressed. This whole sequence takes approximately 1/50th of a second to complete which isn’t a huge amount of time, but the delay could cause problems shooting moving objects as the image would be captured 1/50th of a second after you intended it to.

The following table summarizes the events that must unfold each time a photograph is taken with a leaf shutter SLR.

| Stage | Shutter | Iris | Mirror | Capping Plate |

|

| 1 | Composition | Wide Open | Wide Open | Down | Down |

| 2 | Preparing to Fire | Closed | Stopped Down | Up | Up |

| 3 | Exposure | Open | Stopped Down | Up | Up |

| 4 | Uncocked Shutter | Closed | Wide Open | Up | Up |

| 5 | Wind Lever | Wide Open | Wide Open | Down | Down |

This following YouTube video shows the shutter action of 7 different leaf shutter SLRs. Unfortunately no Kowas were used in the video, but they basically work the same way. On a side note, I want to know where this guy’s supplier is to have that many perfectly working leaf shutter SLRs all at once!

If this sounds like an overly complicated way to make an SLR, you’re right. While overall it did work, the chances for failure were higher for leaf shutter SLRs compared to focal plane SLRs due to the extra moving parts, and the cost to get them repaired was substantial. While I could not find any evidence of this, I would suspect that many repair shops back then might have declined service on models like these for this very reason.

Despite these challenges, that didn’t stop companies like Kodak, Zeiss-Ikon, and Kowa from releasing a variety of leaf shutter SLRs in the 1950s and 60s. Perhaps it was the wide availability of so many quality leaf shutters out there, or that leaf shutters do have the advantage of flash sync capability at all speeds, versus the standard 1/60th speeds of most focal plane shutters of the era. Whatever the reason for the design of the leaf shutter SLR, it proved to be an unreliable way to build a camera and as such, very few are found in working condition today.

This Kowa SE-T actually came to me with a semi-working shutter. When I first received it, I was pleased to see that the shutter did indeed fire, but it was slow at all speeds. In an attempt to try and flush it with lighter fluid, I ended up making the camera worse. It got to the point where the film advance got completely jammed and wouldn’t cock or fire the shutter at all. Back in the fall of 2016, I attempted to disassemble this camera in the hope that I could discover what went wrong with it, and well, I failed. The Kowa SE-T is beyond repair and frankly, I don’t even think I’d want to use it as the constant worry of another shutter failure would be always on my mind while shooting. It is for this reason, that this Kowa SE-T is here as a Camera of the Dead.

If I look past the shutter and reflect upon everything else about the camera, I can say that compared to the Retina Reflex III, the Kowa SE-T has a much cleaner design and it’s controls are easier to use. For one, the SE-T looks like most other SLRs of the era. If no one were to tell you, you would assume this was just another run of the mill Japanese made SLR. All Kowa SLRs are generally compact and lightweight. Compared to the Retina Reflex III, the Kowa SE-T is shorter, and weighs less.

In addition to a more compact design, all of the necessary controls are exactly where you’d expect them to be. The shutter release, exposure counter, and wind lever are all on the right side of the top plate, both the shutter speed and aperture rings are on the lens just like they are on many other cameras, and even the ASA speed selector is on the lens in a similar position to where it resides on most cameras of the era. The Retina Reflex however, has its controls in seemingly random places on the camera, the worst being the aperture selector which is an independent wheel on the bottom of the lens mount.

The SE-T has modern features like a fully coupled match needle TTL CdS exposure meter visible in the viewfinder, a bright Fresnel focus screen with a ground glass circle and split image focus aides, M and X flash sync, and a self timer.

To be perfectly honest with you, I find it to be a damn shame that this camera didn’t come with a focal plane shutter as it’s design, controls, and size make for an extremely compact and easy to use camera. I honestly believe that Kowa SLRs could have been pretty popular in the years after their release as the rest of the camera seems to be well made, and their 6-element coated lenses suggest excellent images. It was not to be however, and what we have now is a curious relic from a short lived era of leaf shutter SLRs that look good on a shelf, but not much else.

I was unable to find any kind of sales estimates for Kowa’s leaf shutter SLRs, but for them to have been in production for over a decade, I have to imagine that they sold reasonably well. Perhaps they were marketed as an entry level SLR for photographers ready to make the switch from a rangefinder to an SLR, without investing large amounts of money into the system cameras made by other companies. In the ad to the left from 1964 for the earlier Kowa SE (the only difference between the SE and SE-T is the lack of a through the lens CdS meter), the big selling point was the camera’s value. At a list price of $115, the Kowa SE was a bargain compared to other SLRs with similar features. When adjusted for inflation, $115 in 1964 is like $903 today. Not cheap, but nowhere near the asking prices of cameras like the Nikon F, Minolta SR-7, or Canon FX.

Kowa’s only other camera at the time was their Kowa Six, which was a medium format SLR, similar to models made by Bronica and Mamiya. The Kowa Six was in production until around 1974, at which time, the company would completely exit the camera business. After that, their product line seemed to switch to other optics products such as sporting scopes, binoculars, and ophthalmic diagnostic equipment. The company still exists today both in North America as Kowa-USA, and in Japan as Kowa Company Limited.

Taron Eyemax (1961)

This is a Taron Eyemax 35mm rangefinder camera made by Nippon Kosokki in 1961. The Eyemax was a mid-level rangefinder that came with either 45mm f/1.8 or f/2.8 lenses. It had a coupled selenium exposure meter located in an elegant chrome frame prominently on top of the camera. The meter was linked to a match needle that was visible in the viewfinder. Match needle systems would become very common in the 1960s, but was still pretty new when this camera was first introduced. The Eyemax was produced for a very short period of time and very little is known about how it was marketed at the time, but it most likely compared favorably to other Japanese made 35mm rangefinders of the era.

Lens: Taronar 45mm f/1.8 coated

Focus: Coupled Coincident Image Rangefinder

Shutter: Citizen MXV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell Meter

Battery: none

Flash Mount: Accessory Cold Shoe and PC MX Sync

Manual: none

My Thoughts

The Taron Eyemax is an interesting camera with a chrome grille prominently located above the lens which strongly resembles the massive chrome grills found on American automobiles and large kitchen appliances of the late 1950s and early 60s. It was this bright chrome grille that really drew my attention when I first saw one. Taron rangefinders aren’t exactly rare, as there are always at least a few of them for sale on eBay at any one time, but finding the Eyemax can be quite difficult. The typeface for the Eyemax logo on the top plate of the camera is very stylized and has a 60s “retro” look to it. The “X” in Eyemax kind of looks like an “H”, and I’ve seen at least a few examples of this camera sold as the Taron Eyemah. In his excellent review of the Eyemax, Simon Hawkett says that his example was sold as the Eyemah.

As hard as it might be to find an Eyemax for sale online, finding information about the camera was even harder. I couldn’t find a user’s manual for this camera online. All the usual sources like Mike Butkus’s camera manual site had nothing for this model. Camerapedia has a very short paragraph about the camera, and a Google image search only returns a few random Flickr and eBay photos of this camera.

The company that made the Eyemax was originally founded in Tokyo around 1940 as Nippon Kōsokki Seisakusho. Their most successful products were NKS shutters that were copies of the German Prontor II shutter. Many Japanese cameras from the 40s and 50s had NKS shutters, including my own Zenobia C. NKS survived World War II and would continue making shutters until 1955 when they would release the first Taron rangefinder camera.

The camera was a cleanly designed and well built 35mm rangefinder that probably sold reasonably well. As was common with many Japanese camera makers with Japanese sounding names, NKS would eventually change it’s name to that of it’s most successful product, which was “Taron”. Taron’s Camerapedia article suggests this happened in 1959, but I am not sure if that’s true as I’ve found camera manuals for other 1960s Taron cameras that still credited the company as some variant of Nippon Kosokki. Although Taron seemed to be pretty active releasing a large variety of cameras in the 1960s, they ended up going out of business sometime in the late 60s. Finding any kind of conclusive information about NKS or Taron, their products, and what became of them was quite difficult and as such is why I have very little information about the Eyemax itself.

In what little information I could find, I found evidence of another camera called the Taron Eye, which I believe was released a year prior to the Eyemax. Both the Eye and the Eyemax have a similar selenium meter prominently located on top of the camera, but only the Eyemax has the unique chrome grille. Compare the picture of a Taron Eye to the left with my Eyemax and you’ll see a number of similarities.

The ad to the right appeared in a 1960 issue of Modern Photography and refers to the Taron Eye as the Eyemagic and from what I can tell, has an identical feature set to the Eyemax. The presence of the suffix -max at the end of Eyemax suggests that the Eyemax was an upgraded model, but I cannot tell what was different, other than the added bling of the chrome grille around the meter.

Both the ad to the right and Sylvain Halgand’s page on the Eyemax suggest that both the Eye and Eyemax sold for around $80, which when adjusted for inflation, is comparable to $651 today.

I came across this example in a lot of other cameras that I picked up from Roberts Camera in Indianapolis, including a Bencini Koroll, a Brumberger 35, a Minolta A5, and broken Edixa SLR. I was pretty excited to get the camera and hopefully put it to good use, but upon it’s arrival, the camera was completely dead. The shutter didn’t work, the focus was stuff, the sprockets in the film compartment would not move when winding the camera, the meter didn’t work, and the leatherette was both moldy and flaking off. The Eyemax was one of the most ‘dead’ cameras I’ve ever acquired. Strangely, other than the flaking body covering, and a dent on the filter ring, it was in pretty decent cosmetic shape. The glass looked clean and free of obvious fungus or mold, the rangefinder seemed to work, and the body itself lacked any major dents or gashes. I wonder if someone had attempted to take this camera apart in the past to fix one problem, and ended up causing even more problems before giving up and putting it back together. It seems odd that so many things could simultaneously go wrong in a camera that otherwise is in nice shape.

I wasn’t too disappointed though, as I’ve shot enough 1960s rangefinders that the experience would have likely been similar to other cameras of the era. I could not find any specifics about the make up of the Taronar lens, but it’s probably a 6-element design that produces nice and sharp results comparable to any other period lens with similar specs.

The biggest appeal for me with this camera are it’s looks. I might just clean this up and possibly replace the leatherette with something else because it looks so good sitting on a shelf. While many Japanese companies in the 60s went for simple and clean designs, Taron put a little pizazz in the Eyemax and I think that’s pretty cool. Maybe one day I’ll find another, and if I do, maybe I’ll review it, but for now, enjoy yet another “Camera of the Dead”!

My Conclusions

I’ve read about and been involved in many discussions online regarding differences between camera users and camera collectors (or even hoarders). If you were to ask my wife or anyone who doesn’t ‘get it’, what they think about my collection, they’d probably tell you it’s absurd. I have nearly 100 cameras when most people are happy with 1 or 2.

My collection pales in comparison to others I’ve met who have several hundreds, or even thousands of models. When I see people with collections that fill a room, I can’t help but feel a little jealous at the vast number of cameras they have, but then I think its such a shame that they just sit there, as display pieces on a shelf. But then I play devil’s advocate with myself and think about how many cameras in my collection I’ve only shot once and then left them sitting on a shelf.

I’ve come to the conclusion that while its great that some people like to use cameras for their intended purpose, its OK to let them sit on a shelf too. If a camera sits on a shelf, should it matter if it works or not? The majority of my collection works, but as this article proves, not all of them do, and for the ones that don’t they still have stories to tell, and I think that’s why it’s important to write about these Cameras of the Dead. For one reason or another, none of these models are able to perform their intended functions any longer. Their days of shooting photographs and capturing memories are past. But they can still serve a purpose, which is to inform people of their existence. A reminder of how things once were and how not everyone accomplished the goal of making a photograph the same way. Every camera has a story to tell, and I want to help tell that story. I think that’s pretty cool!

I *FINALLY* had the chance to read this excellent article. These “Cameras of the Dead” series are just a tad dismaying, as I can feel your pain as I read through your challenges of trying to breathe life into something that simply does not wish to work any more.

You are quite right about the uniqueness of the AL-1 among most makers. In some ways, Pentax sort of had a very similar camera in the ME-F but it actually was designed to be used with a bulky self-focusing lens whose design didn’t really work. The nice offset is that this camera (like other early AF models) has a focus confirmation feature but is not weighed down with internal focusing motors.

Brilliant

Thanks for the article on the Taron Eyemax! I have a Taron Eye I have been working on for several days and I am far from being done servicing this wildly over engineered beast! I also assume the Eyemax is essentially the Eye with a new grill, so be very careful if you decide to take this camera apart! The match needle exposure system is wildly complex. A gear on a shaft transmits exposure information back to the camera body, which drives an eccentric cam around the lens mount, which transmits movement to a follower cam which moves a fan shaped gear up and down in the viewfinder. This drives the red needle you move to match the silver needle, which is the exposure meter. I belatedly have discovered that no matter how many traditional scribe marks I made on the shutter assembly during disassembly, this did not save me from disassociating the gear drive train from the exposure indicator in the viewfinder and now I have a REAL puzzle on my hands. I did, however, get the rangefinder, shutter and aperture working again, so if nothing else, can decouple this system and have a fully manual camera, but I would rather try to return it to normal operating condition if I can. There are many, many “gotchas” in this camera that are readily apparent AFTER you take it apart, so drop me an email if you wish any pointers and I’ll do what I can.

I’m a little behind the eight ball here I’ve just come across your review of the Taron Eyemax. Lightbulb moment “I’m sure I’ve got one of those” sure enough high up on a rarely looked at top shelf was the Eyemax with a bunch of other ’60’s quirky Japanese Rangefinders I collected a few years ago. “I wonder if it works?”, wind the lever, click the release, low & behold the shutter opens & closes. Checking the speed all but the slow ones seem OK, 1 sec is more like 2-3 but once up to 1/8 seem close to accurate, aperature works good, meter is responsive, but seems erratic(plus I’m not 100% sure how it works having no Inst Bk. Rangefinder appears spot on an is nicely aligned but is a bit stiff. Overall I’m pretty happy with it, just need to give it a bit of an external clean and it’ll be sweet as. Thanks for jogging my memory(too many cameras not enough time) -Regards Richard

Great article! I’m happy to report I have both a fully functioning Canon AL-1, and a Topcon Unirex, which is not the Kowa you reviewed, but a leaf-shutter SLR nonetheless. I also have a VERY dead, “Shelf Queen” Kowa SE-

Greg, after posting this Cameras of the Dead article, I ended up coming across both a working Canon AL-1 and a Kowa SET-R, both of which I’ve reviewed here:

https://mikeeckman.com/2018/03/canon-al-1-1982/

https://mikeeckman.com/2017/11/kowa-set-r-1968/

Both are great cameras and ones that I look forward to shooting again!

I own a Kowa SET-R camera that works. It is able to shoot and the meter is operational. I have not had a chance to test it out in the desert earlier today with Kodak Tri X film. I am eager to develop the film, but am questioning the reliability of the shutter speeds.