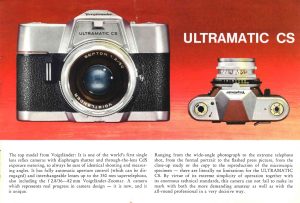

This is a Voigtländer Ultramatic CS, a 35mm SLR camera made by Voigtländer Braunschweig AG starting in 1965. The Ultramatic CS was the top of the line model in Voigtländer’s leaf shutter SLR lineup, starting with the lower cost Bessamatic. The Ultramatic CS was the first leaf shutter SLR with through the lens automatic exposure. It offered interchangeable lenses through Voigtländer’s variation of the Deckel DKL Mount. Using a CdS meter powered by a mercury battery, the camera offered shutter priority auto exposure, or full manual control with match needle functionality. The Ultramatic CS was a very high quality camera that sold for quite a lot of money when it was first released, and is quite desirable by collectors today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2 Voigtländer Septon coated 7-elements

Lens Mount: Voigtländer DKL Bayonet Mount

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Synchro-Compur-V Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: 2x TTL CdS exposure meter w/ viewfinder match needle and Shutter Priority AE

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: PC Port with M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 1103 grams (w/ lens), 859 grams (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/voigtlander_pdf/voigtlander_ultramatic_cs.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Voigtländer Ultramatic CS was the company’s top of the line 35mm camera upon it’s release in 1965. Featuring shutter priority automatic exposure via two CdS meters in the viewfinder, an excellent viewfinder, and a selection of Voigtländer’s excellent lineup of Bessamatic lenses, the Ultramatic CS was a highly regarded camera. Although well built, the camera was also extremely expensive, selling for a price that when adjusted for inflation was over $3000 today. I found the camera to be fun to use, and although it produced entire rolls of excellent photographs, I can’t say I preferred it to my Bessamatic Deluxe with Color-Skopar lens. The Ultramatic CS has always been a prestige piece, and it is still one today. Worthy of addition to any collection, it’s not going to come cheap, but at the very least, you know you’re getting a great camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

The Voigtländer Ultramatic CS’s history closely resembles that of the Bessamatic Deluxe which I reviewed last November, so in an effort not to repeat too much here, I recommend checking out that review if you want to know more about Voigtländer’s excellent lineup of leaf shutter SLRs.

An updated model to the Bessamatic called the Ultramatic made it’s debut in 1962 as the top of the line in Voigtländer’s 35mm lineup. In addition to adding shutter priority automatic exposure through the large selenium exposure meter on the front of the camera, it also added an instant return mirror.

Automatic exposure in a German leaf shutter camera was big news, and having it built by a reputable company like Voigtländer was even bigger as their reputation for making high quality cameras with excellent optics was second to none.

When it was received, the Ultramatic could be bought for $255 body only, $295 with the f/2.8 Color-Skopar, or $365 with their top of the line, 7-element f/2 Septon. These prices when adjusted for inflation compare to $2150, $2500, and $3075 today, making them quite the expensive camera.

In addition to the two 50mm Color-Skopar and Ultron, there were 7 other lenses available for it, ranging from the 35mm f/3.4 Skoparex to the 350mm f/5.6 Super-Dynarex. There was even the world’s first 35mm SLR zoom lens, the 36-82mm Voigtländer Zoomar.

The Ultramatic proved itself to be worthy of it’s reputation and high price initially, but problems began to develop with it’s shutter. Featuring a customized Synchro-Compur shutter developed specifically for Voigtländer, the complexity of the shutter combined with the camera’s automatic rapid return mirror and instant open diaphragm caused issues with the shutter jamming, requiring it to go back in for service.

The problem was such that Voigtländer was unable to satisfactorily resolve it, so both the rapid return mirror and instant open diaphragm were later removed on the updated Ultramatic CS model, released in 1965.

All was not lost though, as the Ultramatic CS upgraded the selenium exposure meter with a pair of through the lens (TTL) CdS meters powered by a single PX13 mercury battery. Some sites suggest that it was the first 35mm leaf shutter SLR to have this feature, but the Topcon Uni beat it by a couple of months. Still, it was a state of the art thing to have back then and with the removal of the instant return mirror, the reliability of the Ultramatic CS was significantly improved from the previous model.

Other changes to the Ultramatic CS over the original Ultramatic were:

- Improved viewfinder with diagonal split image focusing rangefinder

- Removal of filter compensating dial on rewind knob (no longer necessary with TTL metering)

- + / 1 stop exposure compensating dial on the top plate

- Addition of additional safety lock for the rear door release catch to prevent accidental opening

In the quick test to the right from the September 1965 issue of Modern Photography, the reviewer claims the new ground glass viewing screen with diagonal spit image focusing rangefinder to be very good and an improvement from the Bessamatic’s non-focusing Fresnel patterned viewing screen. The one in the Ultramatic CS is ever so slightly darker, but offers full focus ability from corner to corner.

In the quick test to the right from the September 1965 issue of Modern Photography, the reviewer claims the new ground glass viewing screen with diagonal spit image focusing rangefinder to be very good and an improvement from the Bessamatic’s non-focusing Fresnel patterned viewing screen. The one in the Ultramatic CS is ever so slightly darker, but offers full focus ability from corner to corner.

The new model, despite having a more reliable shutter and significantly improved metering system, sold for the same price as the earlier Ultramatic and could be purchased with the Septon lens for $365.

The Ultramatic CS was in production until 1967 at which time the newly integrated Zeiss-Ikon / Voigtländer would share their resources and jointly develop a focal plane SLR called the Icarex 35.

Today, nearly everything Voigtländer ever made is collectible. The more rare the item, the more desirable it is. Find a rare Voigtländer camera in good working condition, and the value escalates ever farther. The Ultramatic CS likely isn’t the most sought after model, but it’s still very desirable. It’s lenses are easily adapted to modern digital cameras using adapters and because of their extreme sharpness, still deliver razor sharp shots today.

My Thoughts

I’ve previously reviewed the Bessmatic Ultra, and gave it high marks for it’s excellent feel, ergonomics, and ease of which I was able to shoot entire rolls of excellent photos…and that was with “only” the Color-Skopar lens. How would the Ultramatic CS compare with the 7-element Septon?

This Ultramatic CS came to me as a loaner from one of my site readers along with a Zeiss-Ikon Contarex. Both the Contarex and Ultramatic CS represent two of the best German SLRs of the 1960s and ones that I’ll eventually put in a head to head comparison in a future article. Sadly, the meter was unresponsive with any battery I put into the camera. Although the battery compartment looked clean, I couldn’t get any activity from the needle, so I just shot the camera using Sunny 16 like I do most of the time.

At 1103 grams, or just under 2.5 lbs, the Ultramatic CS ranks up there as one of the heaviest 35mm cameras I’ve ever handled. Beating the also heavy Bessamatic Ultra which tips the scales at a not svelte 938 grams. The only way you’ll find a camera heavier than this, is to start attaching large telephoto lenses or motor drives to your solid metal cameras.

Like the Bessamatic, the Ultramatic has an incredible feel to it. Voigtländer cameras of this era seem to have a shinier chrome plating than most cameras of the period that gives it a more reflective looking and slick feel to it. Although luxurious in feel, this caused me fits when trying to photograph the camera for this article. The reflective surface made getting nice shots of the chrome difficult, but that’s likely not a concern of most people who would have considered buying this camera for making photographs.

The top plate is pretty sparse, featuring a pop up rewind knob with integrated film reminder disc (more on that later) and a green battery test light. The low profile pentaprism hump looks small, but that’s only because of the tall top plate of the camera. This being a leaf shutter camera, there is no shutter speed selector on the top of the camera. On the far right is a + / 1 exposure compensation dial for the meter.

The rewind knob also functions as the door release, but operating it is not obvious for the first time user. To activate it, you must press the small little circle on the back in the direction of the black arrow, while simultaneously pressing in and to the right on the flat serrated “thing” sticking out of the side. Doing this will cause the rewind knob to pop up part of the way. If you had film in the camera, with the knob in the up position deactivates the film transport for you to rewind the film. Once the film is rewound, pulling up on the rewind knob the rest of the way, releases the door lock and the film door will pop open.

I think Voigtländer was going for an all in one solution for rewinding film and opening the rear door, I wasn’t much of a fan of this setup. For one, the amount of effort required to activate these various parts is more than a little. It’s not a lot, but that flat “thing” has very sharp edges, and it didn’t always feel good on my fingers trying to get the camera open.

With the door open, film loads from left to right onto a fixed take up spool. I did not get a good shot of it, but the Ultramatic’s spool has a very wide opening with a pronounced “finger” that grips one of the film perforations and does a good job of holding onto it. Loading film into the Ultramatic is surprisingly quick, despite there being only one slit in the spool to do it. With practice, you could likely load film in just a couple of seconds.

To the left of the viewfinder is the rectangular battery compartment. In what I think is the cheapest part of the camera, the battery is held in by a black plastic tray that slides out with pressure from your fingernails. With the tray out, a new PX625 equivalent battery slides into position. A red dot on the tray ensures you can only insert it back into the camera the correct way.

Flip the camera over and we find a surprisingly elegant bottom plate. Most cameras don’t have body covering on the bottom, but most cameras aren’t the Ultramatic. Centrally located is the 1/4″ tripod socket.

On the right side is a rather unique exposure counter with two settings for 20 and 36 exposure rolls (24 exposure rolls did not exist when this camera was made). To switch between the two, you press in on the center button and twist with your finger to alternate between the number 20 on the left side, or 36 on the right.

The exposure counter automatically resets each time you open the rear of the camera. When it resets, in 20 exposure mode, the counter is at a diamond at the 23rd exposure. In 36 exposure mode, the counter is at a diamond three past the 36th exposure. Like most Voigtländer cameras of the era, the exposure counter is subtractive, which means it shows the exposures remaining, and not how many have been shot like on most 35mm cameras. The idea with the diamonds is that when loading film, you should have to advance the film and press the shutter three times before reaching the first exposure, which on the Ultramatic would be either 20 or 36. It’s probably more confusing writing it out, than it is in person, but it’s a rather creative way to implement both a 20 and 36 exposure counter using the same automatic resetting device.

The Ultramatic uses the same version of the Deckel DKL mount as the Bessamatic, which means lenses from the two cameras can be swapped with each other, but strangely, not with Voigtländer’s Vitessa T. To remove the lens, simply apply pressure to a flat pin below the 6 o’clock position of the lens mount and rotate the lens counterclockwise. Reattaching the lens is just a matter of aligning two red dots and twisting the lens clockwise until it clicks.

Also visible from the bottom of the shutter is an inner ring for setting the ASA film speed for the meter. Possible choices are 12 – 3200, or if you prefer, DIN numbers 9 – 36.

To the left of the shutter is a long black metal shutter release. The shutter release is threaded on it’s bottom for a shutter release cable. The location of the shutter release is comfortably located for your right index finger.

Looking down upon the shutter and lens, starting closest to the camera body, a narrow shutter speed selector with speeds B through 15 in orange to indicate that the camera should be stabilized to prevent motion blur, and then 30 through 500 in white. Immediately above the shutter speed ring, is a just as narrow aperture ring with choices from f/2 to f/22 plus a red “A” for using the camera in Automatic Exposure mode.

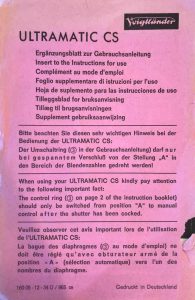

Caution: An addendum that was included with the Ultramatic CS when it was new, warns against switching from Auto to manual control unless the shutter is cocked. This addendum was likely lost over the years with most of these cameras, so I wonder if their poor reputation for reliability was a result of people not heeding this warning. Nevertheless, it’s not something I’d like to try.

While I appreciate camera maker’s efforts to not allow their models to get egregiously big, I was not a fan of the thinness of these rings. Changing them with the camera to your eye is a chore. The shutter speed selector thankfully has slightly larger “ears” which makes it easier to locate which is ideal for when the camera is in AE mode, but if you plan on shooting this camera fully manually, changing these quickly without having to lower it from your eye is not easy.

Further from the body is a clever focusing scale with an adjustable depth of field scale. I am not sure who developed it first, but Voigtländer took a cue from Schneider who had a nearly identical system with two red “fingers” that move closer or farther apart depending on chosen focus distance to show the depth of field at any distance. Since depth of field is unique to each lens, this scale is part of the lens, and not the camera, so changing lenses, changes the scale. This depth of field scale does not operate when the lens is set to “A” or Auto Exposure mode.

Somewhat compensating for the very narrow shutter speed and aperture rings on the shutter, the viewfinder thankfully is one of the best parts of the Ultramatic CS as it is a full information viewfinder. With the camera to your eye, you can see your chosen f/stop and shutter speed above the focusing screen at the top of the viewfinder. The numbers displayed in this window come from a “Judas window” which is the little T-shaped window on the front of the camera above the “Ultramatic CS” logo. Since this window relies on natural light shining down on the lens, these values can be hard to read in low light.

The main viewfinder is a large piece of ground glass with a diagonal split image focusing rangefinder in the center of the viewfinder. The Ultramatic lacks a Fresnel pattern in the focusing scree like other cameras of the era like the Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex which allows for more precise focus across the entire frame, at the expensive of brightness in the corners. The image to the right is a composite of two images I took with my cell phone camera since I was unable to capture both the viewfing screen and Judas window at the same time.

On the left is an f/stop scale that shows the automatically chosen f/stop in auto mode, and a meter reading in manual mode. There are two red zones at the top and bottom of the scale that when in auto mode indicate when proper exposure will not be possible at your chosen shutter speed. With the camera set to a manual f/stop, the camera can be used as a match needle type in which you match your chosen f/stop with the reading from the meter and when the two needles overlap, exposure is correct.

The Voigtländer Ultramatic CS has quite a lot to like. It was Voigtländer’s top of the line 35mm camera upon it’s release and it bested the Bessamatic with a CdS meter and automatic exposure. It is heavy, shiny, and has an awesome lens, so let’s see some sample pics!

My Results

My first roll through the Ultramatic was near the beginning of spring 2019 when the weather was still cool and the skies were gray. There wasn’t a lot of color around, so I chose a roll of what is probably my all time favorite black and white film, Kodak Panatomic-X, or Pan-X for short. The formula of Pan-X has changed over the years, and the rolls I had were from the late 1970s when the film had an ASA speed rating of 32. I’ve shot this film before and know it exposes well at box speed, but just for a small stop of extra light, I shot it as if it were an ASA 25 speed film.

Not wanting to only shoot black and while I decided a roll of color was in order as well, so for that, I went with one of my old standby’s Fuji Superia X-tra 400. Despite being a stop faster than Fujicolor 200, sometimes I think the “X-tra” film gets extra color, so I loaded it up on a recent trip to Cincinatti, Ohio to attend an Ohio Camera Swap, hosted by Dan Hausman. All of the color photos in the gallery below are in or around West Chester, Ohio on September 7th.

The images above look great. I dont think I’ve ever shot a Voigtländer camera that didn’t produce great images. Whether it’s a 3-element f/7.7 Voigtar Anastigmat on the Brillant, 4-element Color-Skpoar on the Bessamatic, or 6-element Ultron on the Vitessa, I’m convinced Voigtländer has never made a bad lens.

My comments on these images are less about the corner to corner razor sharpness, accurate color rendition, and excellent contrast delivered by the 7-element Septon, and more the experience of the camera. I loved the Bessamatic for it’s ergonomics, viewfinder, and ease of which I was able to make great images, and all of that is true of the Ultramatic. Had the meter worked, I would have had automatic exposure, but I certainly won’t hold that against a 54 year old camera.

The viewfinder is bright and has both a diagonal split image focus aide and ground glass circle, the ability to see both shutter speeds and f/stops, and unlike other Voigtländer cameras with bizarre locations for essential controls, everything was exactly where I expected them to be.

I also love the minimalist design of the camera. Unlike many other German cameras, the Ultramatic CS has clean lines, and uncluttered top plate. Even from the front, the camera looks sleek and elegant.

Is the Ultramatic CS a better camera than the Bessamatic Deluxe, sure, on paper it definitely is. But does any of that translate into better photographs or a more enjoyable shooting experience for me as a guy who shoots one or two rolls of film in a camera then writes about it on his blog? Not really.

My lukewarm reaction to the Ultramatic CS is less about any faults or shortcomings of the camera, and more about how really great the Bessamatic is. Considering the collector’s value and rarity of a working Ultramatic CS, if someone were to ask me to recommend a premium leaf shutter German SLR from the 1960s, I’d probably point them to the Bessamatic over this, simply due to value.

But then again, can you really put a price on excellence? The Ultramatic CS is without a doubt an excellent camera and one I’d be lying to you if I said I didn’t want to make a permanent member of my collection.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Ultramatic_CS

http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/entry_C333.html

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=926

Nice. These leaf-shutter SLRs fascinate me for their high complexity.

Me too. They also infuriate me at the rate of which they fail! Between Kowa SLRs, the Zeiss Contaflex, Retina Reflexes, Topcon Unis, and a few other designs, I’m less than 50/50 when it comes to finding leaf shutter SLRs in working condition!

Another good informative write up. Leaf shutters have their advantages, but not for SLR cameras – too complex. I wonder if they will come back with mirrorless cameras. I am thinking of the Pentax Q (leaf shutter lenses) with an electronic viewfinder.

I doubt it. A leaf shutter on a mirrorless would likely have some of the same challenges as on an SLR, in that the shutter would need to open and close twice for each exposure, since the sensor itself is what allows the viewfinder on mirrorless cameras to work. It would need to stay open for composition, close to begin the shutter cycle, then open and close quickly to make the exposure, then open again a second time to allow the viewfinder to work again. Of course, there’s no mirror there, but the shutter would still need to work twice as hard.

Detailed and fascinating review of one of my favorite camera systems from the late 50’s thru the mid 60’s. I have most models from an early Bessamatic through this Ultramatic CS, with I think my favorite being the Bessamatic CS. Just like the ergonomics of it’s body over the two Ultramatics. What I truly love though is the Septon 50/F2 lens. To me this is one of the finest lenses made and rivals anything from Zeiss, Leica, Nikon or Canon, although I will also have to give props to the Topcor 5.8CM/1.4, as being one of my faves. The one drawback I find to all leaf shutter SLR’s compared to the focal plane shutter is the almost universal 1/500 sec top shutter speed. It’s somewhat more difficult to use any faster speed film and stay in the middle apertures especially for me living in bright light Florida without having to consider a polarizer or ND filter which usually becomes a pain. Still, the quality of production and sheer mechanical engineering can not be denied with these cameras and the CHROME….

I agree with you 100%. Voigtländer is one of those companies that made interesting cameras that are fun to use, are gorgeous to look at, and made some of the best lenses out there!

May say that sample photos from the Ultramatic CS are some of the best that I’ve seen on your web site. The Bessamatics may be dated – but when they work, they deliver impressive images.

As the proud owner of both 2 Bessamatics and an Ultramatic with non-functioning selenium meter, they are worth playing with today, just for the chance to use Voigtlander optics from this time period. The lenses never disappoint. Except for the ability to close focus without a diopter, the 50/2 Septon makes my AiS Nikkors seem second rate. I have no qualms using more common Color Skopar.

Like Gary, I do recommend using a ND4 – if you wish to use the intermediate apertures on a sunny day due to the max 1/500th of a second shutter speed. Leaf shutters are better suited for lenses purposely designed for built-in shutter, as in a Hasselblad medium format.

The Ultramatic is truly a unique example of sleek, modern streamlined art deco design. The instant return mirror and shutter operation makes it less rooted in the 1950s, With that said, I find myself reaching for my Bessamatic CS, when stricken by the urge to use my assorted DKL mount lenses.

Thanks for the compliment Andrew. As you noticed, the Ultramatic and Bessamatic are two of my favorite leaf shutter SLRs out there. A third, which has a much more conservative design and less brand appeal, is the Kowa SET-R. If you check out that review, you’ll see I got some similarly excellent results from it. I actually have an updated review of that camera coming very soon where I had a chance to shoot the telephoto lens on that camera too.

I love your camera reviews. Your review of the Ultramatic prompted me to write about my experience with mine just yesterday. Maybe it will help somebody. My Ultramatic is the earlier version with the selenium meter, not the CS version.

Shortly before Thanksgiving, I bought a Bessamatic, Ultramatic and Koday Retina IIIS from an individual that obviously loved them, but wanted money for his wife’s Christmas present. The Bessamatic’s shutter had been working but just failed as he was preparing them for sale, and the Retina’s shutter had also failed recently, but the Ultramatic worked. I also got a 50mm Color-Skopar and a 135mm Super-Dynarex, along with a lens for the Kodak, and one or two cases. All for $90. These are my first DKL mount cameras. As it turned out, the two “broken” cameras were soon functional, and the functional one was soon “broken”.

Amazingly, a YouTube video showed a detailed teardown of a Retina IIIS, so I was able to repair it myself. Interior screws had come loose. The test roll of HP5+ film looks great. This wasn’t my first amateur camera repair, but it was my most complex success.

Another internet tip suggested lighter fluid on the shaft mechanism at the bottom of the mirror box of the Bessamatic. That worked, and I recently shot my first test roll of film. Unfortunately, I used a film I can’t develop since I experimented with Ilford’s XP2, the C41 process b&w film, and haven’t attempted to get it processed due to the virus.

Now, that Ultramatic worked when I bought it, but its shutter failed before I could fire off 10 test firings once I got home. GRRR. The shutter would fire before the film advance stroke was completed. But I found that if I took off the lens and reached into the body to stroke the aperture actuator tab closest to the shutter release first, the shutter would then wind and operate perfectly. But that tab had to be stroked at least twice. Once was not enough. Incredibly odd. So the camera could be used to shoot a test roll, but I’d have to remove the lens and stroke that tab before every shot. So I set it aside until the weather warmed enough that I could operate it without gloves or fear that cold weather would make it even worse. I’ve learned not to use my old cameras in cold weather, fearing the effects on the old lubricants. I think that’s what caused my Bronica to fail last winter. Since them, when I get to the point of “what have I got to lose?” with 50 year old mechanical cameras with shutter failure likely due to grease solidification, I gently heat them up. I fixed my Zeiss ikon Contarex by putting it up in my 150 degree attic for a couple of hours. It remains my favorite camera – in the summer. I’ve had luck with two other cameras using either a hair drier, or my oven at 150 degrees. But be careful!

Just yesterday, I picked up my Ultramatic again to consider shooting a test roll, but stroking that tab now worked only about 80% of the time, making the camera too aggravating to use. The “heat treatment” didn’t work this time. But in the spirit of “what have I got to lose?”, I applied more than a modicum of lighter fluid in that slot. And now the shutter does work consistently, and at all speeds!

I read with alarm your warning that the Ultramatic CS needs to be cocked before moving from automatic to manual operation. That sounds like a “self destruct” function, since I’d eventually and absent-mindedly forget to cock it first, since none of my other cameras require that. I don’t know if that warning applies to my earlier model of Ultramatic, but the manual makes no mention of it. My light meter functions (but needs a correction factor), so I am likely to be switching between auto and manual. Just to be safe, I think I will always keep this camera cocked when I have film in it. Just this morning I made a piece of cardboard to fit into the flash bracket reminding me to “Keep shutter cocked”. I expect to start a test roll today or tomorrow.

Thanks for the insight into your challenges with your new cameras. Sadly, all these DKL mount SLRs are finicky, regardless of who made them. Sometimes, exercise is all they need, otherwise they need more help. It’s good you were able to get some shots from yours.

Whenever this quarantine subsides, I encourage you to get some C41 chemicals so you can do that XP2 (plus regular color film). I find C41 to sometimes be easier than B&W!

Who fixes Ultramatic/Bessamatics????

Dave, I’ve never had it done personally, but I would strongly recommend reaching out to Chris Sherlock at retinarescue.com. He specializes in leaf shutter SLRs and may be able to help you.

Mr. Sherlock has retired. On his web page, he warned that the Retina Reflex was a mess to repair/overhaul.

Thanks for the tip!

Mike, Always enjoy your reviews. I have the selenium Ultramatic. While the DKS mount is compatible with the Bessamatic–not the other way round. To work the Ultramatic’s automatic setting an extra lens to mount coupling is needed, This is shown on each lens with an indented yellow dot. Without this on the lens the auto feature will not work. Tom