This is a Voigtländer VF 135, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Rollei-Werke Franke & Heidecke GmbH in Singapore starting in 1976. The VF 135 is a near-copy of the Rollei XF35 from 1974, omitting that camera’s Flashmatic exposure system, and having a revised top plate. The VF 135 features a 5-element Color-Skoparex lens which was made under license from Carl Zeiss Oberkochen. It also features a coincident image coupled rangefinder, an electronically controlled shutter with full programmed auto exposure, and a top 1/650 shutter speed, all contained in a light weight and compact body. The VF 135 was part of the last generation of fixed lens rangefinders to be produced before the start of the auto-focus point and shoot era.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 40mm f/2.3 Color-Skoparex coated 5-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 3.5 feet / 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder w/ Meter Needle Display, 0.54x Magnification

Shutter: Electronic Metal Blade

Speeds: B, 1/30 – 1/650 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell w/ Programmed Auto Exposure

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: Hot shoe and M and X Flash Sync, 1/30 X-Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, AE Lock

Weight: 354 grams

Manual (English Starts Page 16): https://www.cameramanuals.org/voigtlander_pdf/voigtlander_vf135.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Voigtländer VF 135 was a very late entry into the company’s long running lineup of 35mm rangefinder cameras. Built in Singapore by Rollei, the VF 135 is a simple camera with a rather basic feature set. It includes full programmed automatic exposure, but can be used manually in flash mode. It has a really nice viewfinder, and a 5-element Sonnar design that delivers good, but not great results. This isn’t a camera you should necessarily seek out, but if you were to find one at the right price, you shouldn’t pass up either. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.0 | ||||||

History

Of all camera makers of the past century (or more), Voigtländer is not only the oldest, but also the one that was the hardest to kill. Changing owners multiple times, the brand still technically exists today, but is a shadow of it’s earlier era.

First founded by Johann Christoph Voigtländer in Vienna, Austria in 1756 Voigtländer has a long history of producing optical instruments of all kinds, from simple lenses to scopes, eyeglasses, and so on. Voigtländer’s first camera was an all-metal daguerreotype released in 1841 called the Daguerreotyp-Apparat zum Portraitiren. This camera was made of brass and was shaped somewhat like a bowling pin. There was a fat end where the lens resided, and a thinner end with a ground glass focusing screen and a magnifying eye piece that the photographer would use to get the image in focus.

Over the course of the next 2 decades, Voigtländer would continue to be the world leader in photographic lens manufacturing. In 1862, the company would produce it’s 10,000th Petzval lens. In 1868, Voigtländer’s company headquarters would relocate from it’s original location in Vienna, Austria to Braunschweig, Germany where the company would remain until at least the end of World War II.

Voigtländer wouldn’t release another camera until around 1890 (some sources state it was after 1900), when they would release a Reisekamera which is a generic name meaning “travel camera” in German. Many manufacturers made similar style cameras and it can be extremely difficult to identify who made a particular Reisekamera because the parts were wooden, modular, and lacked any unique differences between all the companies making them at the time. So while it is possible Voigtländer had a variety of these style of cameras, it’s almost impossible now to identify them as an actual Voigtländer model.

As film photography would gain momentum in the 1900s with models from The Eastman Kodak company and other German makers, Voigtländer would eventually make a more serious effort into designing their own cameras. In the first two decades of the 20th century, the company would release a wide range of folding plate cameras with names such as Scheren-Camera, Alpin, Stereophotoskop, and Avus.

Voigtländer had great success around this time as both a maker of fine plate cameras and lenses. In 1915, the company would outgrow it’s original factory in Braunschweig and would move to a larger facility on the other side of the town. Ten years later, in 1925, Voigtländer would be acquired by German chemicals company, Schering AG and the company would make more of a push into roll film cameras like the Superb and Brillant TLRs, and eventually 35mm models like the Vito.

Throughout the mid 20th century, Voigtländer would go on to produce a huge number of cameras, but would struggle to compete with top tier German companies like Leitz, Zeiss-Ikon, and Franke & Heidecke. The company would never make an interchangeable lens 35mm camera to compete with the Leica or Contax, the company’s Vito lineup of 35mm cameras would never match the level of popularity or sales of the Kodak Retina, and the company’s twin lens Superb wouldn’t be produced past the 1930s and no other attempt would be made to compete with the Rolleiflex.

In 1956, Schering AG would sell it’s interest in Voigtländer to Carl Zeiss Oberkochen, where with support from the company who made Zeiss lenses and Prontor and Compur leaf shutters, would expand it’s camera offering. In 1962, Voigtländer would start work on an all new 35mm SLR with a focal plane shutter, which was to be called the Bessaflex, but the camera would be scrapped during the prototype stage. A stagnating German camera market saw more and more competition coming from Japan, and the management at Carl Zeiss saw Voigtländer models are competing with the company’s own Zeiss-Ikon brand. In 1965, the Bessaflex would receive a cosmetic refresh, and would be renamed the Zeiss-Ikon Icarex 35. Zeiss would continue to produce a line of co-branded models featuring both Zeiss-Ikon and Voigtländer names like the Zeiss-Ikon Voigtländer Vitessa 1000SR in 1968.

By 1972 however, the erosion of the German camera market had taken it’s toll on both Zeiss and Voigtländer and Carl Zeiss Oberkochen made the decision to exit the camera making business entirely, focusing entirely on lens making and other optical work. Since they no longer had any need for the Voigtländer brand or the Braunschweig factory where the Icarex SLR was made, Voigtländer was sold once again to Rollei-Werke Franke & Heidecke GmbH, makers of the Rolleiflex TLRs and Rollei 35 compact camera.

Although officially a Zeiss-Ikon product, the Icarex 35 series of cameras were made by Voigtländer and the sale of the company to Rollei allowed Rollei to re-release an updated version of the last version of the Icarex 35 as the Voigtländer VSL 1. The VSL 1 was unchanged from the last Icarex other than the name and was available in both chrome and black bodies. The first 500 or so examples were built in Germany at the Braunschweig factory, but production was later shifted to a factory in Singapore that Rollei owned and also built their highly successful Rollei 35 camera. Quality control of the Singapore made models is said to have been less than that of German models. A name variant of the VSL 1 exists called the Ifbaflex M102 and was made for a French distributor.

Outside of the company’s SLRs, the only other 35mm camera Rollei produced was the highly successful Rollei 35 compact camera, which had been in production since 1966. The Rollei 35 was a scale focus camera, so in an effort to appeal to those who needed some type of focus assistance, in 1974 the company would release a new camera called the Rollei XF35. The XF35 was an entirely new camera compared to the Rollei 35, but shared a similar boxy shape that hinted at the earlier model. The XF35 came with a coupled coincident image rangefinder, and had a 5-element 40mm f/2.3 Sonnar lens which is said to have been licensed from Zeiss. It is not clear what the agreement of that license was, perhaps Zeiss made the lenses for Rollei, or maybe the optical design was built by Rollei or Voigtländer with Zeiss’s permission.

Whatever the case, about a year and a half later, a Voigtländer branded version of the XF35 called the VF 135 was released. The camera was very similar to the XF35 but lost that models’ Flashmatic exposure system and had a new stepped top plate with different cosmetics. The 40mm f/2.3 Sonnar lens was renamed the Color-Skoparex, but appears to be the same exact lens, just with a new name. Also, unlike the Rollei XF35 which was available only in black, the VF 135 was available only in chrome.

I could find no evidence that the Voigtländer VF135 was ever exported to the United States as the few ads I’ve seen from it are either in German or French. The presence of English in the user manual suggested it might have been sold in some English speaking countries, but I cannot tell which. All signs point to this being an entry level camera. The camera uses quite a bit of plastic in it’s design, allowing for a lightweight and compact body, but it does also give a feeling of cheapness.

In the French language ad to the right, the VF 135 sold for 596 F, or less than a third of the Voigtländer VSL 3E SLR, which itself was an economically priced camera. Using an online historical currency convertor, the conversion rate for French Francs to US Dollars in 1978 means the VF 135 would have cost around $125 at the time, which when adjusted for inflation compares to about $550 today.

According to at least one site, the VF 135 was in production until 1980 and was replaced by an even simpler model called the Voigtländer VF35 F which still used a rangefinder, but lacked any manual modes, and came with a downgraded 38mm f/2.8 Voigtar lens.

In 1982, same challenges that doomed Zeiss and Voigtländer in 1972 caused Rollei to file for bankruptcy further mudding the waters of the German photo industry. Ownership of Rollei would transfer to Hannsheinz Porst, owner of Porst Foto. Voigtländer would transfer to PlusFoto and later RingFoto. The name would largely lie dormant throughout the rest of the 1980s and most of the 1990s, at which point the brand would be resurrected once again in a lineup of Japanese made interchangeable lens Voigtländer Bessa cameras. The Cosina built Bessa cameras would be produced from 1999 to 2013.

After the end of the Cosina Voigtländer cameras, the name would continue to be used on a line of photographic lenses that are still produced today, in M39 LTM and Leica M rangefinder mounts, plus a number of SLR mounts like the Nikon F bayonet and others.

Today, Voigtländer is a revered brand among collectors and film shooters alike. Their long and storied history as the world’s oldest optics companies, plus their countless innovative and attractive models make them appealing. With the company’s struggles in their later years, they were owned by multiple companies and not every product enjoyed the same level of appreciation as their earlier models.

The VF 135 being reviewed here is one of the company’s lesser known models. The entire era when Voigtländer was owned by Zeiss and then later Rollei produced some of the brand’s least exciting models, so if this is a camera you’d like to one day own, you likely won’t encounter too much competition from other collectors. That doesn’t mean the camera isn’t worth considering though. It is a rare example of a late 1970s camera with a modern viewfinder, full programmed auto exposure, and in a compact and lightweight design.

My Thoughts

Voigtländer is a brand that needs no introduction (at least not on this site), as the company has produced some of the most wonderful cameras of the 20th century. Models like the Superb TLR, Vitessa L rangefinder, and Bessamatic SLR are as beautiful as they are sold. Made of all metal and glass, these cameras are precision works of art that represent the best of the German camera industry.

This Voigtländer is not like those cameras. Weighing a feathery 354 grams with a battery installed. the VF 135 could be the lightest Voigtländer ever made. The top and bottom plates of the camera, and possibly the door, are made from a very thin metal, but a majority of the camera is plastic. Inside the film compartment you can see the inner body is made of a plastic that sort of looks like a hard Styrofoam. The rewind knob, shutter release, parts of the lens mount, and the aperture ring are all plastic as well.

Now, to be fair, plastic isn’t always bad, many cameras have used plastic in their construction to great success, but in terms of tactile feel of this camera, this feels more like the cheaply made discount Singaporean camera it is.

The Voigtländer VF 135 is meant to be easy to use, and this is reflected in the simplicity of the camera’s top plate. Starting on the left is the black plastic rewind knob with fold out handle. The handle itself is made of plastic too, so be sure not to abuse it as I am certain it would easily break. In the middle is the flash hot shoe which has an X-sync speed of only 1/30. Next is the film advance lever which thankfully is metal, as a plastic handle would most certainly break off with repeated use. The lever itself requires very minimal amount of effort to move and moves with a loud ratcheting sound. A full movement is about 180 degrees and must be done in one single motion as smaller intermittent motions are not allowed. Above it is the black plastic shutter release button which is threaded for a cable release, and finally the automatic resetting exposure counter. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made on the camera.

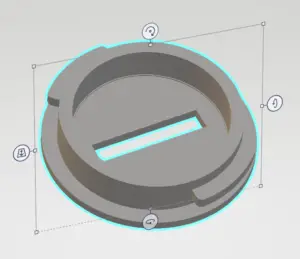

The base of the camera has a black plastic rewind release button, a black metal 1/4″ tripod socket, and a plastic cap for the battery compartment. When this camera came to me, it had it’s original plastic cap, however the very first time I attempted to take it off, it broke into three pieces with very minimal effort. I am not sure if some previous battery had leaked, compromising the plastic, or if the plastic material it was made up of aged poorer than other parts of the camera, but whatever the case, it was no longer usable. Thankfully, I was able to talk to my friend Mark Faulkner who not only had the same camera, but also is adept at 3D printing and was able to take his cap and duplicate it for me.

Around back is the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder, the back of the film advance lever, and that’s all. The pebbled black body covering from the front extends over the entire door and was not peeling or showing any signs of aging on this camera.

On the side are two chrome metal strap lugs and nothing else. The presence of strap lugs on any camera is always a welcome sight, although the Voigtländer VF 135 is so light, this is camera that could actually be used with a wrist strap just as effectively. From the side you also get a look at the simplicity of the shutter and lens as there is only the focus ring around it.

Open the back of the camera by lifting up on the rewind lever and the right hinged film door reveals the film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed plastic take up spool. The spool doesn’t have slits in the traditional sense, but rather had a “U” shaped channel which you can insert the film leader through and fold over, so that when winding the camera, it catches the leader and winds it up. It’s not the most elegant method I’ve seen, but it does work.

On the inside of the film door is a black painted metal film pressure plate covered in divots which help reduce friction as film passes over it. To one side is a chrome roller to help film pass smoothly over the sprockets, and on the other side a rectangular piece of foam that is there to help stabilize the cassette. The Voigtländer VF 135 lacks any sort of light seal material. The door channels are fairly deep and the door hinge perhaps relies on the plastic body to help maintain light tightness. One last thing is that opening the film door, reveals the camera’s serial number imprinted into the left side of the camera, beneath where the door latches.

Looking down upon the shutter and lens, the only thing to see is the focus scale in both feet and meters. The scale goes from 3.5 feet to Infinity in orange, and 1 meter to Infinity in black. Like many 1970s rangefinders, the movement of the focus ring from minimum to maximum focus is very short. Based on a rough guess, I’d say a complete motion is between 30 and 40 degrees. Such a short movement is convenient for quick changes to focus distance, but at the expense of precision as small movements of the ring make for large adjustments to distance.

Flip the camera over, and on the bottom of the shutter is the aperture control for flash photography and the setting for putting the camera in full Auto Exposure mode. The Voigtländer VF 135 lacks any sort of shutter speed control as the shutter is controlled entirely by the auto exposure system. For flash photography, manually setting the aperture to any f/stop from f/2.3 to f/16 sets the shutter at a fixed 1/30 speed. If you came across one of these cameras with a dead meter, or just didn’t want to rely on the auto exposure system, you could shoot it manually by using a slower film speed, and metering for various f/stops and a fixed 1/30 shutter speed.

Up front, around the perimeter of the lens is a black plastic ring for setting the film speed. A small window to the right of the lens shows both ASA and DIN speeds from 25 to 400 and 15 to 27 respectively. Opposite of the film speed window is a round window for the CdS meter, which is contained within the lens’s 46mm threaded filter ring. That such a simple camera supports filters and that using a filter won’t negatively impact the meter is an unexpected feature. Finally, below and to the left of the shutter on the front face of the camera is a mechanical self-timer lever. The self-timer is triggered by the shutter release, so once it is wound up, pressing the shutter release will fire the shutter after an approximate 8 second delay.

The viewfinder is one of the most unexpectedly nice features of the Voigtländer VF 135. The main part of the viewfinder has a slight purple tint with the projected frame lines and circular rangefinder spot in white. Contrast is very good on both the frame lines and rangefinder patch. This could be a symptom of a rangefinder that’s not as old as other rangefinders I’ve tested, or this one just has some rangefinder magic that only cameras from the 1970s benefitted from. Whichever the case, this is one of the nicest rangefinders I’ve used. The frame lines do not automatically correct for parallax, but two small lines near the top are to be used at close focus to indicate the top of the frame. I was able to see the entire image with the frame lines while wearing prescription glasses with no difficulty.

Along the side of the viewfinder window is a meter readout showing all combinations of shutter speeds and f/stops from the programmed auto exposure system. Unlike more advanced metering systems on SLRs and higher end cameras, the relationship between shutter speeds and f/stops is one to one. As the meter detects light, a needle moves up and down pointing to whichever combination the camera intends to use. If you’d like to lock in your exposure read out and recompose your image, a half press of the shutter release will trap the needle, locking in your reading, allowing you to move the camera and press the shutter release the rest of the way to expose the image. At the very bottom of the scale near the 1/30 and 2.3 setting is a red area that when the needle moves into, warns you about underexposure, but will not prevent you from still pressing the shutter release. A word of caution is that when the camera is not in Auto mode, the meter needle still responds to light, but it’s settings are not used. There is no type of reminder in the viewfinder that the AE system has been deactivated.

Repairs

The Voigtländer VF 135 came to me in excellent condition and everything seemed to work, however the first time I went to put in a new battery, unscrewing the original plastic cap for the battery compartment caused it to break into three pieces. The plastic became brittle over time and with a minimal amount of pressure, it shattered.

The Voigtländer VF 135 came to me in excellent condition and everything seemed to work, however the first time I went to put in a new battery, unscrewing the original plastic cap for the battery compartment caused it to break into three pieces. The plastic became brittle over time and with a minimal amount of pressure, it shattered.

Thankfully, my friend and fellow camera collector, Mark Faulkner, both had another copy of this camera and a 3D printer and was able to fabricate a new cap for me that worked perfectly. If you find yourself in a similar situation and need a new battery cap, here is the file he used to create the cap. Please note that I know nothing about 3D printers, and have no idea how to use one, but he assures me that anyone with experience will know what to do with this file.

https://mikeeckman.com/media/VF135BatteryCover.stl

My Results

For the first roll of film through the VF 135, I chose a slightly expired roll of Kodak Portra 160NC. This is film I had experience shooting before and found that it best exposed if shot like an ASA 100 speed film, so that’s what I did. I shot the film in early October 2022, so I had hoped to get some fall colors on my roll, but as luck would have it, summer ran long in my area, so the trees didn’t start to develop any good colors until after I was done with the roll.

Even before shooting a single image in the Voigtländer VF 135, it was clear to me that this was a cheaply built, and inexpensive camera from an era when 35mm rangefinders had almost completely fallen out of favor. But I like 35mm rangefinders, and compared to many of the ones in my collection, this one is less old, had a really bright and easy to use viewfinder, and it had a Sonnar lens. I was pretty eager to shoot it thinking that perhaps this could become my “go to” rangefinder camera for when I want to shoot some candid photos, as it is small, light weight, and easy to use.

Upon taking the images from the Paterson tank, I could see that everything looked good, and the exposure seemed to be correct. After scanning the images into my computer however, I could still see the exposure was good, the colors were good, but the images were a tad softer than I had anticipated.

Sure, I shouldn’t expect images with the sharpness of a 7-element Septon or a 6-element Biotar, but I have seen wonderful shots from 4-element Tessars, and other 5-element lenses like the Plover 2.8 in the Auto Terra Super. Somehow the images from the f/2.3 Color-Skoparex just seemed to be flat. There was a bit of vignetting in the corners which I expect to see in sub 6-element lenses, but the vignetting didn’t give the images any particular character. They just seemed to be those of a cheap lens on a cheap camera. Of course, they didn’t look terrible, but I was a tad disappointed.

The Voigtländer VF 135 comes from a curious era in the timeline of 35mm cameras. By the time of it’s release, most photographers had either leveled up to an SLR, or were happy with inexpensive point and shoot cameras. The dawn of the auto focus era was barely a year away, but upon it’s release would render manual focus entry level cameras like this obsolete.

I have to wonder though, that as with any new technology, if a small subset of photographers wanted a simple camera that they could focus themselves, and models like the VF 135 would have been the right match for them. Whatever the case, this camera was not produced for long, and few were made, suggesting otherwise.

The Voigtländer VF 135 did it’s job with little complaint. I really liked the viewfinder, and found the rangefinder easy enough to use, although I did miss focus on a few, but otherwise produced good, but not remarkable images. I really thought the 5-element Skoparex would have done a better job, but I don’t believe that it did bad enough to where the target audience would have noticed.

The manual focus operation and light weight, plastic feeling body, is a strange combination as my brain has been accustomed to metal manual focus cameras and plastic auto focus ones. The very short throw of the rangefinder wasn’t my favorite, but was on par with what other brands like Konica, Minolta, and Yashica would putting out at the time as any error in focus should fall within the depth of field of the 40mm lens.

The simplest summary I can give of this camera is that it’s not terrible. It does some things well, but for every “pro”, there’s going to be more than one “con”. The Voigtländer VF 135 is a curious camera from the era in which it was released, and for that, is worthy of addition to your collection. Make no mistake, it might say “Voigtländer”, but this isn’t like other Voigtländers.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Voigtl%C3%A4nder_VF_135

https://dcdeveloped.wordpress.com/2016/12/11/vf-135/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GcTUvgRzQCw

https://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/appareil-13083.html

Good review. I always wanted a Rollei XF35, but was deterred by the cheap looking construction. As to the lackluster performance of the Rollei made lens, I have a Contax T with the Zeiss Sonnar f/2.8 lens (albeit 38mm vs. 40mm) and that lens produces outstanding images with a ‘3D effect’ that I rarely see with other film cameras.

I know two other people, one with the Rollei XF35 and the other with the Voigtländer version and their results were similar to mine. Sadly, it just seems as though these cameras deliver disappointing results. The Contax T, though as you mentioned, is a stellar camera!

That street in front of your home may be the most-photographed location in America!

You’re probably right! Also, my bathroom mirror is probably the most photographed reflection of anywhere in America! 🙂

Mike,

In 1975, I was looking to purchase a small rangefinder to carry along in a bicycling trip to Scotland, My photographer friend invited me to see what was available in a small photo store near him in Central NJ. We went to look, and found two models they were selling, the Voigtländer VF 135 and the Olympus 35 RD. It so happened that the Voigtländer representative was in the store at the time and gave me an in-depth sales pitch, with my friend filling in the qualities of both as well as the Olympus. The rep said it was his last one and something about that the Voigtländer would be hard to get later, especially with the spec’d.lens it had on it. My future photographer wife, whom I was dating at the time, had an Olympus OM 1n. Needed less to say, I walked out with the Olympus. She still has hers and I still have mine. But I always wondered what would’ve happened if I had chose the Voigtländer…

Little typo, great article as always!

“Made of all metal and glass, these cameras are precision works of art that represent the gest of the German camera industry.”

Could it be that the VF135 has a thorium lens? I have run into one of these and measure elevated levels of radiation.